Featured topics

This day in history

Find out who was born, who died and other significant events from this day in history

History in Images

A young victim of the atrocities committed by Belgium in the Congo stands next to a missionary.

Image Source:

www.wikimedia.org

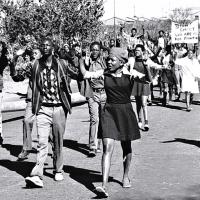

Riot police play a game of soccer with youths in Nyanga on 27 August 1976. Photo by John Paisley

Image Source:

www.lib.uct.ac.za

A certificate of slavery for an infant named Sophie, dated 1827 Cape of Good Hope.

Image Source:

www.theculturetrip.com

Riot police attempt to block the way of workers leaving a May Day meeting at Khotso House in Johannesburg in May 1985.

Image Source:

www.digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za