Early Beginnings of the African Film Industry:

During the British colonial rule over Kenya, Uganda, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland and the Gold Coast in the late 19th and early 20th century, the British aspired to find various methods of “educating” the Natives and “enlightening” them about their “civilized” way of life. Therefore, in 1935 the British Colonial Office decided to sponsor and to establish the “Bantu Educational Cinema Unit”. [1] This unit ran from 1935 until 1937 and was intended to be run as a method of “civilizing” the natives in the British colonies. The director of the unit was, Major Leslie Allen Notcutt, who was previously the owner of a plantation in Kenya and thought to have significant knowledge of Africa. Notcutt ran the unit and decided to use local actors as it would have a greater influence on the colonies and minimize costs. However, in 1937 Notcutt convinced the British Colonial Office to initiate separate film units in the British colonies, Northern Rhodesia, Kenya, the Gold Coast and Uganda, and centralize its control from London. [2] Consequently, in 1948, the British Colonial Office finally decided to establish a “Gold Coast Film Unit”, [3] and ultimately initiated the beginning of the Gold Coast’s (present-day Ghana) film industry.

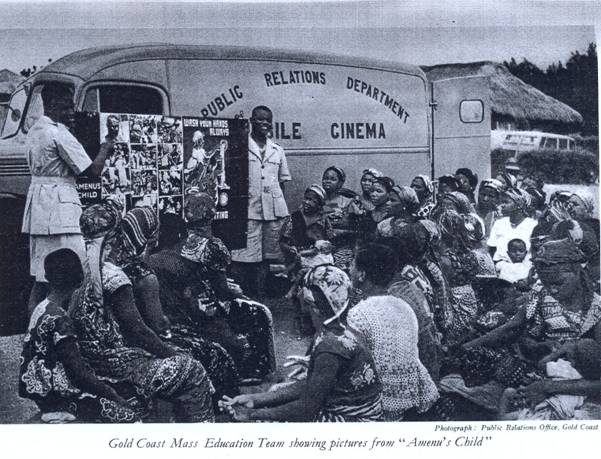

One of the Colonial Film Unit’s “Mobile Cinema” mobile units. Showing “Amenu’s Child” to a town in the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) Image source

One of the Colonial Film Unit’s “Mobile Cinema” mobile units. Showing “Amenu’s Child” to a town in the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) Image source

The Establishment of the Gold Coast Film Unit

With the Gold Coast Film Unit established and a new demand for African filmmakers and actors, the Colonial Film Unit decided to open a film school in Accra. [4] Although this sounds like a dream for an aspiring film industry, the film school in Accra was actually designed to control the local film industry. For example, instead of showing local people existing films and building on previous knowledge, the unit decided that Africans were too “primitive” and therefore, only basic filmmaking skills should be taught. [5] Another negative aspect to the film unit was that it significantly used propaganda to justify British rule and civilization. In order to demonstrate European superiority, many of these films ridiculed and depicted African traditions as superstitions. [6] Although the Gold Coast Film Unit had various negative aspects, it also paved the way for the Ghanaian film industry to expand. Therefore, when Ghana gained its independence in 1957, Kwame Nkrumah (the new Ghanaian president) decided to build on the industry’s existing infrastructures and added production, editing and distribution facilities. [7] This would ultimately mark a new phase in the Ghanaian film industry.

The Ghanaian Film Industry under Nkrumah

During the Nkrumah regime, 1957-1966, the Ghanaian film industry became one of the most sophisticated film industries in Africa. [8] Nkrumah viewed film as an almost perfect strategy to build a nation under the same values and drives. [9] Nkrumah decided to nationalize the Gold Coast film unit and changed its name to the “State Film Industry Corporation” and then eventually changed it again to the “Ghana Film Industry Corporation” (GFIO). [10] Under Nkrumah’s reign, the Ghanaian film industry was almost completely monopolized by the Ghana Film Industry Corporation. In fact, in 1959 a Censorship Board was created in order to exert control over the industry by deciding which productions to fund and screen, as well as deciding which international films were allowed to be shown in Ghanaian cinemas. Although the shift in power in the film industry created an improvement in the production of films between 1957 and 1966, it became evident that the Ghanaian film industry would remain an industry of propaganda.

A Declining Ghanaian Film Industry

When Nkrumah was overthrown in 1966, the films produced during his time were confiscated and a new system was created to be implemented in the Ghana Film Industry Corporation. [11] The new system allowed for Ghanaian films to be co-produced and co-directed by parties outside of Ghana. Although this decision was made to ‘save’ the Ghanaian film industry, it just proved to alienate the industry further. For example, the state started reducing their funds in the industry as they felt that the industry should look at obtaining funds from external sources. This caused a decline in the Ghanaian feature-length films produced. [12] Furthermore, it seemed as if the television network was the only place willing to screen Ghanaian films as the Cinematic Mainstream (screenings in cinema houses) was reserved for international films. [13] Consequently, in the period from 1966 to the 1980s only approximately 20 Ghanaian films were made. [14] Due to the lack of state support and funding, and an overall economic decline in Ghana, the film industry hit rock-bottom once again.

Ghallywood African Film Village in Accra established by William Akuffo. Image source

Ghallywood African Film Village in Accra established by William Akuffo. Image source

Enter William Akuffo and the Rise of Video Films in Ghana

Due to the monopoly held by the Ghana Film Industry Corporation and the lack of funds, Ghanaians started to move their focus to more independent structures. This movement was significantly fuelled by William Akuffo, an independent and self-taught filmmaker. [15] Like many others, because Akuffo was unable to gain funds from the state for his film, he decided to take matters into his own hands and shoot his film completely out of his own pocket. [16] Akuffo followed a “four walling” method (where the filmmaker rents a studio or a stage for the full duration of the movie and keeps the ticket revenues for himself, instead of paying a percentage to the theatre owner), where shot his film on a low budget with a video camera and screened the film in the same “self-produced” studio. Finally, in 1987 he released the feature-length video film, Zinabu [17] The release of this film caused a boom in the video film industry in Ghana as it inspired many self-taught filmmakers to make similar films that dealt with representing the daily realities of Ghanaian culture and life. [18] Furthermore, these films were easier to produce and distribute as one only needed a video camera, a video compact disc and a screen. Quickly, new independent cinemas were built, film libraries were created and on almost every corner of the streets in Accra there were banners and posters advertising new video films. [19] The Ghanaian film industry therefore, entered a new phase yet again. The “Ghallywood” phase – where Ghana’s film industry is solely determined by pop-culture and demand.

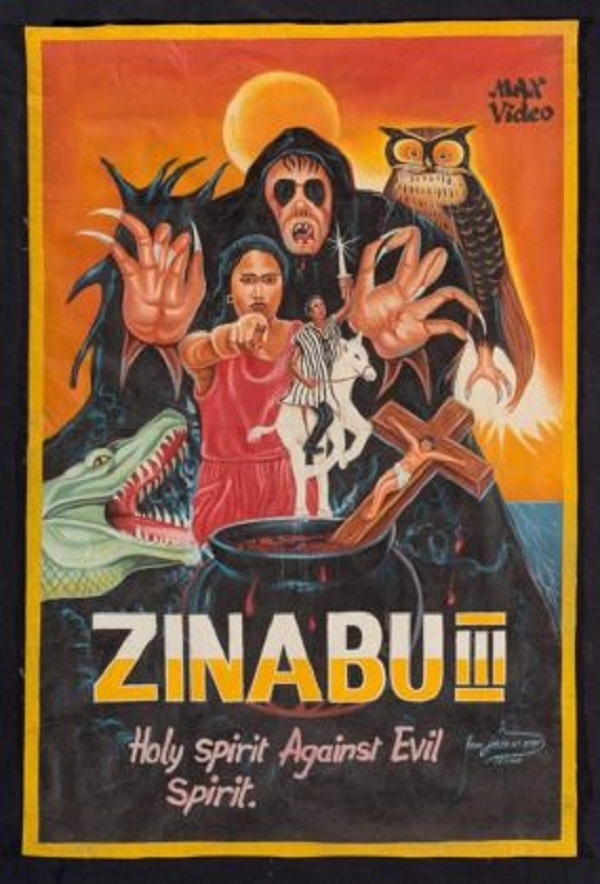

Poster of Zinabu, the film released by William Akuffo in 1987. Image source

Poster of Zinabu, the film released by William Akuffo in 1987. Image source

The Impact of Video Films: Popular Culture

The video film boom of the 1980s and 1990s had a major impact on popular culture in Ghana. For the first time, since British colonial rule, films depicted the modern beliefs and concerns of Ghanaian people. [20] These films had a moral twist to the story where the locals could relate to the everyday lives of modern society. This was also in almost direct contrast with the Nkrumah era of filmmaking, which produced conservative and traditionalist films. [21] Through this, it became evident that the average “John Doe” and “Jane Doe” preferred low quality films with relatable moral messages over higher quality cinema. Interestingly, the new popular culture generated from video-film also paved the way for entrepreneurs and new businesses. For example, numerous artists started painting posters for local Ghanaian, as well as international films. These posters coincided with the new and more “open” popular culture created by the video film industry as it depicted romance and/or gore. [22] In a sense, video film became an industry for the people, by the people.

The Impact of Video Film: Demand and Supply

Before the video film boom of the 1980s and1990s, the Ghanaian film industry was significantly only available to the elite, as they were the only Ghanaians able to afford to go to the cinemas. [23] However, with the affordability of video films, almost any Ghanaian was able to get their hands on the tapes and almost any Ghanaian was able to make films. Consequently, this demand and supply ultimately had two lasting effects on the economic sustainability surrounding video films. Firstly, due to the films being distributed on tape, each film could easily be copied and redistributed illegally. [24] Therefore, causing the Ghanaian film industry to be highly unpredictable as many filmmakers had no way of determining whether their films were going to succeed or fail. For example, a filmmaker would be able to produce two successful video films and would not be able to make enough profits to generate a third one. [25]

Secondly, although the low-quality films did not bother the average Ghanaian, it did affect Ghana’s influence on a larger spectrum. For example, Ghanaian films rarely do well at African film festivals because they are easily recognizable by their lack of technical, narrative and cinematic sophistication. [26] Consequently, the Nigerian film industry, “Nollywood”, keeps overshadowing Ghallywood, as Nigerian filmmakers have bigger budgets, higher quality films and a wider reach for their market – almost completely covering Africa’s sub-Saharan audiences. [27] It should however be noted that many Ghanaians did not mind the lower quality of the films shown to them, they simply enjoyed them because for the first time they were being represented. [28] Through these instances, it is evident that Ghana’s “film-industry-success-story” becomes a question of cultural values versus economic values.

The Impact of Video Film: The State and GFIO Loses Control

When discussing the impact of video films on cinema in Ghana, and keeping in mind that the Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIO) was owned by the state, one important question is raised: What role does the GFIO play in all of this? Although a video boom (the clear rise in demand and supply of video films) should have motivated the GFIO to invest more funds into the industry, the GFIO decided to rather act as a third-party and allow external investment and gain. For example, in exchange to host the independent film premieres, the GFIO would offer editing and production services to the self-trained filmmakers. [29] Another point of impact was that the state was losing control over censorship. For example, due to the high rate of illegal copying and distribution, the Censorship Board could not control the various depictions of “sex, violence, burglary, racial prejudice and female discrimination” in the video films. [30] To an extent, the GFIO was losing control over the new “Ghallywood”. Therefore, the state decided to sell approximately 70% of the GFIO’s shares to “Sistem Televisyen Malaysua Berhard of Kuala Lumpur”, a Malaysian production company. [31] Although this seemed to be a final attempt to save the “old” film industry, it, in a sense, made it worse. The GFIO changed into the “Gama Media System LTD”, and the new company was unable to breathe life back into the existing systems, as well as failing to establish new ones. [32] Therefore, many believe that Ghana’s Film Industry (or at least the traditional “cinema” component) may be doomed to keep failing.

An empty Rex Cinema that does not play films anymore (2013). Image source

An empty Rex Cinema that does not play films anymore (2013). Image source

The Rise of Ghanaian Video Films: The Rise or Fall of Ghallywood?

When looking at the history of the film industry, it is evident that Ghana plays a pivotal role in Africa. This is significantly due to Ghana being one of the first African countries to become independent, as well as being one of the first African countries to develop their own film industry in the post-colonial era. This, however, did have its own problems.

Ghana’s film industry has gone through many highs and lows – from the Colonial Film Unit to the Nkrumah Regime to Ghallywood. When studying the existing academia surrounding Ghallywood, it also becomes clear that many academics seem not to agree on whether the video film industry is the hero or the villain of Ghana’s film industry. However, when looking at some of the points discussed, it seems as though it may be both. The video film industry could be seen as a vigilante - a self-appointed group who decides to take matters into their hands without legal authority.

End Notes

[1] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 1. ↵

[2] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 2. ↵

[3] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 1. ↵

[4] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, pp. 2-5. ↵

[5] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 4. ↵

[6] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 4. ↵

[7] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 6. ↵

[8] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 6. ↵

[9] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 1. ↵

[10] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 2. ↵

[11] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 6. ↵

[12] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 94. ↵

[13] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 94. ↵

[14] M. Diawara.: African Cinema: Politics & Culture, p. 6. ↵

[15] J. Haynes.: “Video Boom: Nigeria and Ghana”, Postcolonial Text, (3), (2), 2007, p. 1. ↵

[16] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 4. ↵

[17] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 4. ↵

[18] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 95. ↵

[19] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 97. ↵

[20] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 5. ↵

[21] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 5. ↵

[22] R.L. Brown.: The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/02/ghanas-wild-golden-age-of-movie-posters/458949/ (Accessed 4 February 2016). ↵

[23] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 97. ↵

[24] J. Haynes.: “Video Boom: Nigeria and Ghana”, Postcolonial Text, (3), (2), 2007, p. 3. ↵

[25] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 98. ↵

[26] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 95. ↵

[27] J. Haynes.: “Video Boom: Nigeria and Ghana”, Postcolonial Text, (3), (2), 2007, p. 4. ↵

[28] F. Ogunleye.: African Video Film Today, p. 4. ↵

[29] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 94. ↵

[30] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 99. ↵

[31] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 99. ↵

[32] B. Meyer.: “Popular Ghanaian Cinema and ‘African Heritage’”, African Today, (46), (2), 1999, p. 99. ↵