The reaction of the outside world to the development of apartheid was widespread, and by the 1980s posed a sustained challenge to the South African regime, which, facing myriad internal and external threats, eventually capitulated to make way for a new, democratic dispensation.

While countries throughout the world took various measures to weaken and topple apartheid, it was the anti-apartheid movements in the United Kingdom (UK), Holland and the United States of America (USA) that mounted the most serious of these challenges to the apartheid state, the UK’s perhaps being the most effective of all such organisations throughout the world.

By the late 1980s the UK’s Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) had unleashed a wide range of campaigns and established branches throughout the country. From small beginnings, the AAM developed a campaign that became one of the most powerful international solidarity movements in history, a model that has subsequently been used to weaken or displace many other dictatorial regimes.

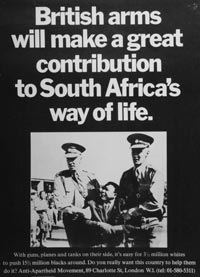

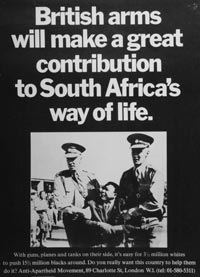

A poster produced in 1971 by the British Anti Apartheid Movement protesting British Arms to South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive

A poster produced in 1971 by the British Anti Apartheid Movement protesting British Arms to South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive

The AAM developed links with political parties and other powerful forces to put in place and reinforce effective measures to destabilise every aspect of apartheid structure, mounting economic, cultural, trade and sports boycotts which resulted in sanctions campaigns supported by governments throughout the world.

By its nature, the AAM was a co-ordinating machine – unable itself to achieve its goals, it persuaded individuals, organisations, political structures and governments to take whatever actions would be necessary to achieve the isolation and weakening of the apartheid state. It’s function was to make powerful actors – such as governments, political parties, trade unions and union federations or the United Nations, but also masses of individuals acting in concert – take significant decisions that had material and, often, historic effects.

The success of the AAM was to slowly, over three decades, bring awareness of the issues to the British public, and to pressure the British and other governments to eventually throttle the apartheid machine by stopping trade, cutting off oil supplies and access to arms, and isolating white South Africa to the point that it was forced to dismantle its oppressive regime.

With nothing more than three, four or five paid staff working out of tiny offices, but hundreds of volunteers and a range of contacts from the highest echelons of power to the everyday citizen, the AAM went a considerable way towards bringing down one of the most repugnant systems in the 20th century.

Britain took over the Cape in 1795 and, after relinquishing control, recolonised the territory during its war with France in the early 19th century. British capital controlled the diamond and gold mines discovered in the late 19th century.

After vanquishing the Boers in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 (now referred to as the South African War), Britain granted dominion status to the Union of South Africa in 1910.

By the late 1950s, Britain was one of South Africa’s most significant trading partners, with more than 30 percent of South Africa’s imports coming from the UK, and 28 percent of South Africa’s exports going to Britain. Besides the economic relationship, Britain enjoyed close relations with its former colony, and between 1946 and 1959, 113,000 Britons had settled in South Africa.

However, other aspects of British culture eventually worked against white domination. Since the 19th century, London became home to exiles from every part of the world, notably to Karl Marx, who wrote his most famous and influential tome, Das Kapital, in the British Library. Similarly, South Africans fleeing from apartheid in the early 1950s settled in the increasingly cosmopolitan capital of the British Empire, and set up structures that took on a life of their own. Vella Pillay, Tennyson Makiwane, Abdul Minty, Yusuf Dadoo, Kader Asmal, Oliver Tambo and later Thabo Mbeki and the Pahad brothers (Aziz and Essop), among many others, all settled in England for periods and used it as a base from which to conduct the struggle against apartheid.

It was Vella Pilay and Tennyson Makiwane who first established the germ of the Anti-Apartheid Movement on British soil. They began holding meetings in the 1950s and planned the first boycotts of South African products, which eventually culminated in the highly influential AAM.

Beginnings: Boycotts in the Fifties

On 26 June 1959, the Committee of African Organisations (CAO) held a meeting at Holbourne Hall in London, calling for the British public to boycott South African products, especially fruit, which was widely available in towns and cities throughout the UK. Julius Nyerere, then leader of the Tanganyikan African National Union (later to become president of Tanzania) and Kanyama Chiume of the Nyasaland African National Congress were the main speakers, and the Congress Movement’s Tennyson Makiwane African National Congress (ANC) and Vella Pillay South African Indian Congress (SAIC) added their voices to the appeal.

In November 1959 a Boycott Committee was formed, and the CAO’s Dennis Phombeah was made chairman of the body. Other organisations played an important role in the committee, including the Movement for Colonial Freedom, Christian Action, and the Universities and New Left Review. Patrick van Rensburg of the South African Liberal Party also took on a significant role, and he asked Chief Albert Luthuli to issue a statement calling for an international boycott, which Luthuli did in a press release dated 21 December 1959. The AAM came to regard Luthuli’s statement as its founding document.

According to Kader Asmal: ‘If any event galvanised the Boycott Movement into action it was Chief Albert Luthuli’s plea for sanctions”¦’ Luthuli’s statement read: ‘I appeal to all governments throughout the world, to people everywhere, to all organisations and institutions in every land and at every level to act now to impose such sanctions on South Africa that will bring about the vital necessary change and avert what can become the greatest African tragedy of our time.’

Demonstration at Trafalgar Square organized by the Anti Apartheid Movement. Source: Museum of London and Henry Grant.

Demonstration at Trafalgar Square organized by the Anti Apartheid Movement. Source: Museum of London and Henry Grant.

The Boycott Committee set about organising for a month of boycott action in the New Year, and support came from a wide range of sources, including student bodies, unions, various newspapers, writers and artists and the Liberal and Labour parties. British public opinion was overwhelmingly against apartheid, especially in such communities as those from the Caribbean, and the committee tried to tap into this sentiment to win support. However, in some quarters the idea of a boycott was anathema – except for a few church leaders, most churches failed to heed the call. Most members of the Conservative Party also refused to support the call. Indeed, when Prime Minister Harold MacMillan made his famous ‘Winds of Change’ speech in the South African Parliament in February 1960, he condemned the boycott.

Other organisations were more forthcoming, and in December 1959 the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress, the vast union federation, officially backed the call for a boycott.

The boycott month, set for March 1960, began with a march to Trafalgar Square, where the South African High Commission was based, on 28 February 1960. As many as 15,000 held a rally at Trafalgar Square after the march, and speakers included Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell, Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe, and Tennyson Makiwane, with Father Trevor Huddleston in the chair. The event received favourable coverage in the press, and a Gallup poll found that 27 percent of those polled supported the boycott.

The Sixties - Sharpeville and After

When police fired upon anti-pass protesters in Sharpeville on 21 March 1960, there was widespread international condemnation of the apartheid regime. British newspapers splashed the massacre on their front pages, and for almost a week hundreds of people demonstrated outside the SA High Commission in Trafalgar Square. While the call for boycotts had been a huge success, the massacre reinforced the British public’s abhorrence of apartheid.

The subsequent banning of the liberation organisations had the effect of sending many ANC and PAC members into exile, and increased the ranks of the organisations’ offices abroad, especially in London. Some have argued that Sharpeville precipitated the formation of the AAM, but the Boycott Committee had already in mid-March made the decision to internationalise the boycott. When the ANC, now underground, called on the United Nations to impose economic sanctions on South Africa, the resolve of the Boycott Committee to expand the campaign was strengthened, and the movement took on its new name, the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

At the Boycott Committee’s meeting of 20 April 1960, the minutes reflected the name change. Yusuf Dadoo, a leader of the SACP and SAIC who had recently arrived in London, suggested that the AAM call on the UN to impose economic sanctions, and that the AAM call on the union movement and African states not to handle oil headed for South Africa.

The transformation of the Boycott Committee into the AAM saw the movement shift its tactics: the call for economic sanctions became a call for regime change, set within a discourse of national liberation, rather than a moral plea to help nudge the apartheid government to reform. However, the call also became a threat to the financial interests of sectors of the British economy, and put the AAM on a path of conflict with powerful corporate blocs and conservative politicians.

Anti Apartheid Movement Activities in the Sixties

With South Africa set to become a republic in May 1961, the AAM called for the country to be expelled from the Commonwealth. When newly independent African states joined in the call to expel the country, South Africa was forced to withdraw from the body. Barbara Castle, the chair of the AAM’s London committee, organised a 72-hour vigil to publicise the issue.

The AAM organised a ‘Penny Pledge’ campaign, appealing to British people to donate a penny to the movement and sign a pledge to boycott South African products. The boycott campaign was supported by the Labour Party, but the party stopped short of calling for economic sanctions. Labour’s support would take on an erratic pattern in the following years: when Oliver Tambo had difficulty in entering Britain, the party intervened; but it did not support the AAM when it organised a speaking tour for Tambo.

The AAM organised the International Conference on Economic Sanctions Against South Africa, held in April 1964, which saw delegates from 40 countries in attendance. At the meeting, Abdul Minty and Vella Pillay met with ES Reddy, the secretary of the UN’s Special Committee Against Apartheid, and forged a relationship that would continue until the fall of apartheid.

Following the conclusion of the Rivonia Trial, in which Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders were sentenced to life imprisonment, the UN Security Council set up a panel of experts to look at ways to oppose apartheid. The AAM set up the World Campaign for the Release of South African Political Prisoners, and launched a worldwide petition, which was signed by 194,000 people. The AAM organised a letter campaign, calling on people and organisations to bombard the South African government with letters demanding the release of the Rivonia Trialists.

When the accused were sentenced on 11 June 1964, 50 MPs marched to South Africa House in Trafalgar Square. On 18 June, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 191, calling on South Africa to release all political prisoners.

The AAM was instrumental in getting various councils to oppose sport and cultural contacts with South Africans. It worked with the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC) to get South Africa excluded from the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964.

SANROC button calling for the rejection of Apartheid in sport. Source: African Activist Archive

SANROC button calling for the rejection of Apartheid in sport. Source: African Activist Archive

The AAM continually updated its list of South African products, and kept the issue in the public eye, especially through its newspaper, the bi-monthly Anti-Apartheid Bulletin. The movement explored ways to further the boycott, and expanded its activities to include sport and cultural boycotts. Having opposed the Springbok Rugby tour of 1960, the AAM organised demonstrations at every match of the Springbok cricket team in 1965. On the advice of the Labour government, the Queen did not attend one such match at Lords.

Love of Labour Lost

When the Labour Party won the election in 1964, Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced in Parliament on 17 November that his government would stop all arms sales to South Africa.

Nonetheless, Labour failed to halt already agreed contracts, and continued to supply naval spares to the South African navy. Labour was reluctant to support the AAM in all its campaigns, especially if these threatened the economic interests of the country. It failed to heed the report of the UN Security Council’s panel of experts on sanctions, who argued that sanctions were feasible. Instead, Labour ministers considered the Vorster regime as more pragmatic than that of Verwoerd, and argued that Britain could exert a positive influence on Vorster.

Faced with disappointment, the AAM reviewed its policies and strategies, and decided to broaden these and make them more effective.

When Rhodesia’s Ian Smith made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain on 11 November 1965, a series of effects followed. With Rhodesia forming a bloc with South Africa, the AAM began to campaign against South Africa’s neighbour and ally, stretching the resources and capacity of the movement. The AAM also began to work more closely with the liberation movements of Namibia (then South West Africa) and Mozambique.

Faced with a crisis in its international relations, the Labour government considered taking on Pretoria as an ally, and dangled as a carrot the possibility of lifting the arms embargo. The AAM was devastated by this development, and Abdul Minty wrote to the Labour government expressing the AAM’s view. Eventually, Harold Wilson prevailed over his rivals and left the embargo in place, but the incident shook the AAM’s relation to the Labour Party.

By the late 1960s, the AAM had lost ground as other issues took centre stage in British public opinion. Abdul Minty concluded that ‘once apartheid and racialism were great moral issues, now it is seen in the economic light’.

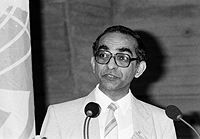

Abdul Minty one leading figures in the Anti Apartheid Movement speaking at a session of the World Conference on Sanctions Against South Africa. Photographer: Michel Claude, Source: United Nations.

Abdul Minty one leading figures in the Anti Apartheid Movement speaking at a session of the World Conference on Sanctions Against South Africa. Photographer: Michel Claude, Source: United Nations.

When the Labour government agreed to joint naval exercises with the South African Navy, the AAM asked Barbara Castle and David Ennals, both Labour ministers and former AAM presidents, to resign from either the AAM or the Labour Party. The episode triggered rifts within the AAM over strategy and tactics, and the movement resolved to develop bases among students, trade unions and antiracist organisations, and to attenuate its emphasis on parliamentary lobbying.

The AAM also reviewed its sanctions campaign, and instead of relying on governments, decided to expose individual companies doing business with South Africa.

The AAM began to express support for armed struggle when the ANC’s military wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), and militants from Zimbabwe’s ZANU embarked on the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns in July 1967. But it had to be careful not to alienate less radical sectors of the British public.

Other campaigns continued, and in 1967 the AAM tried to stop the British Lions from touring South Africa. The D’Oliveira incident in 1968 – when the South African government refused to allow the British cricketing tour because it was captained by Basil D’Oliveira, a ‘Coloured’ South African – highlighted the reasons why the public should heed the AAM’s various boycott campaigns. In 1969 various sports fixtures were disrupted by the Young Liberals in league with SANROC.

The Seventies

In the early Seventies, the ANC was at its lowest point, but the AAM began the decade with its most successful campaign ever, ‘Stop the Seventy Tour’. When the Labour Party came to power in 1974, the AAM found that despite promises and expectations, the party was unable to throw its weight behind the movement. The AAM then went on a drive to cultivate a mass base among students, unions and churches.

The AAM had also at its 1967 annual conference decided on measures that would make the sanctions campaign more practical: it began to focus on disinvestment, putting pressure on specific companies to pull out of South Africa. The Seventies saw this aspect of AAM activity take off.

With more and more political trials underway in South Africa, the AAM worked with the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) and in 1973 set up Southern Africa the Imprisoned Society (SATIS) to draw attention to the plight of political detainees.

When the Black Consciousness leaders were arrested and banned in 1974, the AAM mounted campaigns in support of the South African Student Organisation (SASO).

Stopping the Springboks

With the Springboks due to play a series of 23 games throughout Britain, the AAM’s Hugh Geach and SANROC’s Dennis Brutus established the ‘Stop the Seventy Tour Committee’ (STST), with Peter Hain as the committee’s spokesperson.

Under the umbrella of the AAM and the STST, scores of organisations in each region arranged mass protests in concert with direct action tactics (such as pitch invasions) over the three months of the tour (from 30 October 1969 to 2 February 1970).

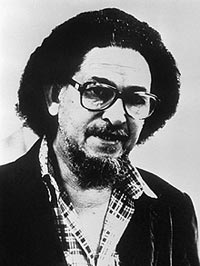

Dennis Brutus played a leading role in SANROC and worked closely in AAM in protests against Apartheid in sport. Source: The Telegraph.

Dennis Brutus played a leading role in SANROC and worked closely in AAM in protests against Apartheid in sport. Source: The Telegraph.

The protests were massively successful, with thousands turning out at the games to protest while the STST used direct action tactics to disrupt whichever games they could. A planned cricket tour soon after drew an even more intense series of protests. Virtually every sector of British society was involved, from the Labour and Liberal parties to the Afro-Caribbean communities, the churches, unions, students and the British aristocracy. African countries threatened to boycott the Commonwealth Games to be held in Edinburgh in July 1970 and the government, facing an election, ordered the Cricket Council to call off the tour.

The tours and protests received huge coverage in the British press, and the issue of apartheid was condemned from every quarter.

The Conservative Party won the elections and announced that it would end the embargo and resume sales of military equipment to South Africa. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Trade Union Congress (TUC) urged Prime Minister Ted Heath not to break the UN Security Council resolution by selling arms to South Africa. The AAM organised a rally at Trafalgar Square which was attended by 10,000 people, and a declaration in favour of the embargo was signed by 100,000 people. Abdul Minty flew to Singapore to present the declaration to the Commonwealth heads of state conference. The Conservative government sold only a few helicopters to South Africa, although it never officially reversed its position.

Constructive Engagement vs Disinvestment

In the early 1970s, proponents of a less radical approach to dismantling apartheid began to gain ground when arguments were made for ‘constructive engagement’, which proposed that aid and trade would more effectively dissolve apartheid and that economic growth would bring a share of the cake to all. Instead of disinvestment, these critics proposed that British firms be called upon to raise the wages of their Black workers and provide training and upward mobility.

BJ Vorster and Malawi's president Kamuzu Banda in 1971. From: http://www.aboutmalawi.net/2011/07/photos-of-hastings-kamuzu-banda.html

BJ Vorster and Malawi's president Kamuzu Banda in 1971. From: http://www.aboutmalawi.net/2011/07/photos-of-hastings-kamuzu-banda.html

Meanwhile Vorster’s policy of détente – an attempt to woo African leaders and neutralise possible enemies – was yielding results: Malawi’s Banda visited South Africa, as did leaders from various other African countries.

In contrast, the AAM’s disinvesment campaign sought to show how British firms profited from apartheid policies, and called on sympathetic forces such as trade unions to withdraw any investments they might have in the South African economy, and persuade the government to halt new investments.

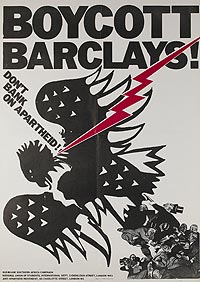

When it was discovered that Barclays Bank had a tiny investment in the Cabora Basa dam project in Mozambique, the AAM targeted the bank, which had thousands of branches throughout the UK.

Building a mass base

The failure of the Labour Party to support the AAM’s most important campaigns led to disillusionment with parliamentary politics and prompted a shift in the AAM. The movement now began to cultivate students, unions, church groupings, women’s organisations and other sectors in an attempt to build a mass base that would ensure the success of its campaigns.

Students

At the 1970 spring conference of the National Union of Students (NUS), the students passed a resolution that they would support the armed struggle against apartheid. The union’s president, Trevor Fisk, who had met with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) leaders on a trip to South Africa, went against the AAM’s cultural boycott when he supported the idea of academics taking up work at universities in South Africa. The students voted him out, and Jack Straw was elected in Fisk’s place, marking a radicalisation of the student union, which called for a total cultural, sporting and academic boycott.

The infrastructure of the NUS, with branches at every university in the UK, became a resource for the AAM, and students became the largest sector of the AAM’s membership. The two organisations joined forces in September 1971, and joint conferences were held annually from July 1972. Scottish students launched their own network in May 1973, and were especially active.

Unions

The AAM also began to build a base among unions. Some unions had supported the movement since its formation. however, the Trades Union Congress, which had strong links with the conservative, white-dominated TUCSA in South Africa, turned down an invitation to attend the AAM’s national committee in 1961. The TUC continued a policy of constructive engagement, and became a battleground as more unions began to forge links with the AAM, many trying to radicalise the TUC’s policies and get the federation to support the AAM.

In 1971, 14 unions were AAM affiliates. It took the 1976 Soweto uprising to bring a flood of affiliates, and by 1980 35 national trade unions were affiliates. More and more unions began to refuse to handle South African goods, and the International Conference of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) asked workers to observe a week of action in November 1976. An International Labour Organisation (ILO) conference in 1977 also proposed a week of action, during which the Union of Postal Workers asked its members to stop telephonic communication and not handle post to and from South Africa.

Churches

Churches in the UK generally took a conservative position, although he British Council of Churches (BCC) called on the Labour government in 1964 to impose an arms embargo and supported sports boycotts. Yet, the council withheld support for more radical measures, such as a World Council of Churches (WCC) call for international corporations to withdraw from South Africa. Most churches followed the policy of constructive engagement, but the Methodist Church and the Church of Scotland tended towards a more radical policy towards South Africa.

During the 1970s the churches fostered links with the Black Consciousness Movement rather than the ANC, SACP or PAC. The Black Allied Workers Union (BAWU) and the Black People’s Convention (BPC) members attended seminars organised by the British Council of Churches and the Church of England’s Board for Social Responsibility.

After Beyers Naude’s Christian Institute was banned in 1977, the British churches began to take more radical positions. Manas Buthelezi preached at Westminster Abbey in 1977 and Desmond Tutu participated in events on British soil in 1978.

A shift occurred at the BCC’s general assembly in 1979, and the council accepted a policy of ‘progressive disengagement’ in place of the constructive engagement it had practised. The move rendered the churches more susceptible to closer ties with the AAM.

AAM activities in the late Seventies

When Angola and Mozambique achieved independence in 1975, the geopolitics of the region took a dramatic turn, and South Africa was isolated more than ever. Nevertheless, it was the unrest in Soweto in 1976 that changed the country and started a process that would lead to renewed resistance and eventually negotiations. The AAM, which had always had a special relation to the ANC, now had to contend with new forces in the liberation movement, and the re-emergence of the trade union movement in 1973 brought yet another aspect to the struggle.

SATIS launched an emergency campaign in May 1976 after Joseph Mdluli was killed in detention in March 1976. When Steve Biko was killed in 1977, the AAM called for an inquiry, a call that received backing from many groups.

Labour’s foreign secretary David Owen attended an IDAF-organised memorial service for Biko at St Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1977 the Commonwealth governments endorsed the Gleneagles Agreement, an informal measure to ‘take every step discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa’.

The new Labour government, elected in 1974, terminated the Simon’s Town Agreement, but continued to hold joint naval exercises. The AAM exposed NATO collaboration with the apartheid government in Project Advokaat, a secret underground naval surveillance system, and in March 1975 organised a mass rally against joint naval exercises and collaboration with the apartheid state.

A poster produced in 1971 by the British Anti Apartheid Movement protesting British Arms to South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive

A poster produced in 1971 by the British Anti Apartheid Movement protesting British Arms to South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive

In 1977, reports confirmed that South Africa was set to test a nuclear bomb, and despite warnings from Western governments not to go ahead, the regime exploded a nuclear bomb in the south Atlantic in October 1979. The AAM linked up with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in a drive to ‘Stop the Apartheid Bomb’.

After June 1976, the government became more willing to heed the AAM. In May 1977 the government announced that it was no longer supplying South Africa with NATO codification data. Labour’s Foreign Secretary, David Owen, proved to be more receptive than any other minister had ever been, and twice met with the AAM in 1977, agreeing to investigate transgressions of the arms ban.

The government even dropped its veto at the UN and voted for a mandatory arms embargo, something no previous British government had done. Labour’s NEC took a more radical line than the government, and pushed for a freeze on new investment.

But the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 meant that the AAM could rely even less on the British government to back its campaigns.

The Eighties

The success of Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party in the first democratic election in Zimbabwe in March 1980 left South Africa exposed as the only racist regime remaining in Africa, and freed the badly stretched AAM to focus its scarce resources on its South African campaigns. In its attempts to isolate South Africa, the AAM sought to influence the UN, the Commonwealth and the European Economic Community (EEC) to pressure the new Thatcher government to support international sanctions.

Joseph N. Garba (left) Chairman of the Special Committee against Apartheid and Reverend Trevor Huddleston President of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement at a press conference, 10 October 1984, Photographer: Milton Grant, United Nations.

Joseph N. Garba (left) Chairman of the Special Committee against Apartheid and Reverend Trevor Huddleston President of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement at a press conference, 10 October 1984, Photographer: Milton Grant, United Nations.

In the sporting field, the AAM worked with SANROC to compile a list of sportsmen and women who broke the boycott – more than 700 had visited South Africa between 1980 and 1987. Rugby was the biggest challenge, and the British Lions tour of South Africa went ahead in 1980. The Rugby Football Union sent another team in 1984, but pressure from the AAM and ministers ensured it was the last to do so.

The revolution in Iran in 1979 saw South Africa’s main source of crude oil cut off, and the UN Special Committee, together with the Holland Committee on South Africa and the church initiative Kairos, organised a seminar which called for an oil embargo against South Africa. The AAM launched a campaign against multinational companies, especially Shell and BP, which were involved in the oil trade with South Africa. Other organisations involved in the oil trade also came under the spotlight, and the AAM pressured the British government to cut South Africa off from benefitting in any way from North Sea oil. After an ILO conference in 1983, maritime unions joined in the action, and the cost of oil became much more expensive for South Africa.

The cultural boycott, endorsed in a resolution of the UN General Assembly in 1980, was reinforced with the drawing up of a register of entertainers who had performed in South Africa. Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey and David Essex, who had performed at Sun City, pledged that they would not return to South Africa. Local authorities, such as the Greater London Council, took action against anyone on the register and anyone who refused to make the pledge. When the president of Equity (the British drama association), Derek Bond, announced that he would break the boycott, members of Equity voted to ban members from performing in South Africa. Bond was forced to resign.

Visits to Britain by black South African artists were difficult to target, and the group Bahamutsi performed in England, as did a group from the Market Theatre. Paul Simon’s work with black South African musicians for his Graceland album came under fire, although the album hit the charts in the UK. The academic boycott proved difficult to implement, even though the Association of University Teachers voted in 1980 to boycott all links with South African universities.

However, other initiatives were more successful. The rebel cricket tour by a team captained by Mike Gating in 1990 was forced to cut short the tour.

The Thatcher Government

From the beginning Margaret Thatcher’s opposition to apartheid was steeped in reluctance. The Pretoria regime, seen as an ally in the Cold War, enjoyed a kind of covert support from the new Conservative government. Unable to openly side with a racist regime, and publicly expressing abhorrence of apartheid, Thatcher used every loophole to oppose sanctions, preferring ‘dialogue, steady pressure and exploitation on SA provided by our economic involvement there’.

According to Christabel Gurney: ‘At the moment when the AAM was at last succeeding in building a coalition of support for the isolation of apartheid, it was confronted by a prime minister who was implacably opposed to sanctions.’

Nonetheless, it is a testament to the AAM that even a government as conservative as Thatcher’s was forced to take steps against Pretoria that eventually pushed it to the negotiating table. The fact that Thatcher was positioned to the right of most of her cabinet meant that certain forces within the Conservative Party were more receptive to the call to end apartheid.

In the face of widespread scepticism towards PW Botha’s Tripartite Parliament that persisted in the exclusion of Black South Africans, Thatcher refused to condemn the constitutional makeover of apartheid, preferring to give it ‘the test of time’. When Botha tried to garner international acceptance for his new scheme by touring Europe in June 1984, the British government was the only Western power to extend an invitation to Botha. The AAM ensured that Botha got a frosty reception, and a wide range of groupings protested at his visit. So effective was the anti-Botha lobby that Thatcher was forced to meet with the leaders of the AAM – in the first and only such occasion. After talks with Trevor Huddleston and Abdul Minty, Thatcher issued a statement recommitting the British government to the arms embargo and the Gleneagles Agreement. On the day of the meeting between Botha and Thatcher, 50,000 people marched to an AAM rally in Hyde Park.

British opposition to Thatcher’s increasingly conservative rule resonated with an anti-apartheid ethos, and opposition to Thatcher naturally morphed into opposition to apartheid.

The Tide Turns

By the mid-80s, the AAM had mobilised a vast network and succeeded in largely overwhelming opposition to sanctions. Local authorities, trade unions and churches now came on board in an unprecedented and sustained attempt to force the Pretoria regime to the negotiating table.

Local authorities throughout the UK took concrete steps in support of the AAM’s agenda:

Sheffield; London’s Camden Council; London boroughs Brent, Islington, Tower Hamlets and Newcastle-upon-Tyne; Scotland’s huge Strathclyde Regional Council; all expressed opposition to apartheid in concrete measures. According to Gurney, ‘By 1985, more than 120 local authorities, representing 66 percent of the British population, had taken some form of anti-apartheid action.’

Britain’s huge union federation, the TUC, previously at arm’s length from the AAM, now came out in full support of UN sanctions. In 1981, at its annual congress, it passed its first resolution calling for sanctions. General secretary Len Murray met with an AAM delegation in June 1982, in a first for the TUC’s highest official. The TUC rallied to the side of African workers fired by Wilson-Rowntree in South Africa, and in 1985 passed a resolution calling on unions to support the AAM’s boycott campaigns.

Against the advice of the AAM, the TUC’s new general secretary, Norman Willis, and Ron Todd, chair of the federation’s international committee, visited South Africa in July 1986. Nevertheless, the visit impressed on the duo the horrors of apartheid and prompted them to take effective measures. Todd was appalled by the realities of apartheid, and when the pair visited a family in Alexandra township, hippos descended on them and they were arrested. From then on the TUC made South Africa a priority, even producing a film promoting the boycott, which was seen in cinemas throughout the UK.

Churches, invited by the South African Council of Churches, attended the launch in 1985 of the Kairos document, which called on Christians to recognise the period as one calling for unprecedented interventions. In 1986 major church bodies called for targeted sanctions.

The AAM’s campaigns throughout the subsequent period were supported by huge swathes of British citizens, and international measures required less effort to persuade partners and governments, although the Thatcher government always needed to be cajoled.

Hitting the South African Economy

The AAM’s campaign against Barclays Bank came to a dramatic end when, in November 1986, the bank pulled out of South Africa. With students throughout the UK closing their Barclays accounts, the bank admitted: ‘Our customer base was beginning to be adversely affected.’

Between 1986 and 1988 as many as 55 British companies sold off their subsidiaries in South Africa and a further 19 reduced their investments. The number of British companies investing in South Africa fell by 20 percent. Standard Chartered, the second largest bank in South Africa, also pulled out, as did insurance companies Norwich Union and Legal & General, and arms manufacturer Vickers.

Poster produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement calling on people to boycott Barclays Bank and force the bank to withdraw from South Africa, South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive.

Poster produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement calling on people to boycott Barclays Bank and force the bank to withdraw from South Africa, South Africa, Source: African Activist Archive.

When Chase Manhattan Bank decided it would not roll over its loans to South Africa, the government in August 1985 announced a moratorium on the repayment of foreign loans. Foreign exchange markets and the Johannesburg Stock Exchange were temporarily closed, and other banks followed the lead of Chase.

With the re-election of Thatcher’s Conservative Party in 1987, the AAM began to focus on public support for sanctions instead of putting all its efforts into getting the government to impose sanctions. The AAM launched a ‘People’s Sanctions’ campaign, asking ordinary members of the public to boycott South African goods. It targeted the largest supermarket chains, Tesco and Sainsbury’s, urging them to stop buying products from South Africa. The People’s Sanctions campaigns were remarkably successful – a Harris poll fond that 51 percent of Britons were in favour of some form of sanctions.

In various ‘days of action’ activists piled up South African goods onto trolleys and then refused to pay for them, causing blockages and inconvenience, while a ‘Boycott Bandwagon’ toured the country and spread the message. The AAM produced a film, The Fruits of Fear, promoting the boycott.

New targets were identified: gold, coal and tourism. In conjunction with End Loans to Southern Africa (ELTSA), the ANC and the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO), the AAM set up the World Gold Commission to look into the issue of gold sanctions. The movement also joined with the UK’s National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) to set up an embargo of South African coal, while tour operators were targeted in the campaign to stop Brits from holidaying in South Africa.

Anti-apartheid movements from other countries, in particular Holland and the US, focused on oil giant Shell, which jointly owned one of the largest refineries in South Africa and had interests in coal mining and petrochemical industries. The AAM joined in these efforts, and launched a total boycott of Shell products in the UK. Some local authorities moved their heating oil contracts from Shell, and the company’s Annual General Meeting (AGM was broken up by protesters.

Focus on Repression

With the declaration of the state of emergency in July 1985, activists inside South Africa were increasingly coming under harsh laws: detentions, political trials and, for some, death sentences. The AAM urged churches, trade unions and students to draw attention to the plight of detainees. SATIS convened a UDF Treason Trial Campaign Committee in 1985, calling for the withdrawal of charges. Trevor Huddleston launched a petition, ‘Free All Apartheid’s Detainees’, in June 1987, which 300,000 people signed, and a campaign was launched to oppose the repression of trade unionists, who were being targeted by the apartheid state.

Solomon Mahlangu was hanged in April 1979 despite a UN Security Council appeal, and 14 other activists were condemned to death over the next 14 years. Because of international pressure, seven of them were spared the death sentence. The AAM and Southern Africa: the Imprisoned Society (SATIS) held vigils outside South Africa House. Women’s groups took up the case of Theresa Ramashamola, one of the Sharpeville Six accused, while other AAM activists drew attention to the Upington Seven. The AAM met with Thatcher’s foreign minister, Lynda Chalker, and eventually Thatcher was pressured into voicing her concerns to PW Botha and, in the case of the Sharpeville Six, an indefinite stay of execution was announced in July 1988.

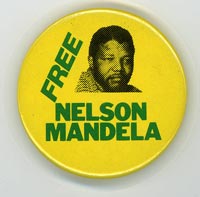

The Free Mandela Campaign

After the launch of the Free Mandela campaign in South Africa in 1980, the AAM also took up the cause, which had already been underway because of the efforts of ES Reddy, the secretary of the UN Special Committee. Together with the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF), the AAM produced a film about Mandela, called South Africa’s Other Leader, which was watched by millions during PW Botha’s visit to the UK in 1984.

Mandela was awarded the Freedom of the City of Glasgow in August 1981, and similar awards were made by 50 councils and local authorities over the next decade. The street in which the AAM had its offices was renamed Mandela Street. The AAM urged Britons to send postcards to the jailed leader, which they did in their thousands.

Button of the Free Mandela Campaign produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement. Source: African Activist Archive.

Button of the Free Mandela Campaign produced by the Anti Apartheid Movement. Source: African Activist Archive.

The AAM set up the Free Nelson Mandela co-ordinating committee in 1983 to liaise with the many organisations that called for his freedom. Musicians were especially responsive to the call to free Mandela, and several artists and bands released songs making the call, including The Sussed and The Special AKA, which recorded Free Nelson Mandela, written by Jerry Dammers. Hugh Masekela played at a ‘Festival of African Sounds’ in 1983 at London’s Alexander Palace, commemorating Mandela’s 65th birthday.

Dammers linked up with Dali Tambo (son of Oliver Tambo) to form Artists Against Apartheid, which organised a rock concert on Clapham Common in July 1986. Thabo Mbeki spoke at the festival, which was attended by 250,000 people.

The AAM’s ‘Freedom At 70’ campaign, lasting more than a month, began with a concert and ended with a rally five weeks later. Dammers worked with the AAM to organise a huge concert at Wembley to kick off the campaign. Held on 11 June 1988, the concert featured Simple Minds, Peter Gabriel, Whitney Houston, Stevie Wonder and Sting, among scores of others, and 72,000 people attended the event. The event was screened live by the BBC over nine hours, and the broadcast was made available to TV stations in 63 countries. Headlined ‘Nelson Mandela: a 70th Birthday Tribute’, the concert was a huge success, and made Mandela a household name in the UK as well as elsewhere.

The day after the concert, Oliver Tambo and Trevor Huddleston addressed a rally in Glasgow, attended by 15,000 people. Twenty five marchers, each representing a year of Mandela’s 25-year incarceration, then set out on a walk to London, stopping along the way at 40 towns and cities where events were held to call for Mandela’s freedom. The marchers arrived in London on the eve of Mandela’s 70th birthday, 17th July 1988, at a rally at Hyde Park. The next day, Tambo gave each of the marchers a bust of Mandela.

Sting was one of many artists at the AAM organized concert to pressurize the Apartheid government to release Mandela. Source: Iconicphotogalleries

Sting was one of many artists at the AAM organized concert to pressurize the Apartheid government to release Mandela. Source: Iconicphotogalleries

The success of the campaign was reflected in the findings of a poll, which revealed that 70 percent of respondents thought Mandela should be freed, and 58 percent thought Thatcher should do more to get Mandela out of prison. It was also reflected in a near doubling of the AAM’s membership, from 8,500 in 1986 to 19,410 in March 1989. Even Thatcher was swayed by the campaign, and she assured Huddleston: ‘We raise his (Mandela’s) case regularly with the South African government.’

The decade ended with the formation of the Southern African Coalition (SAC), a grouping made up of churches, trade unions, NGOs, local authorities and development agencies. SAC, in which the AAM was a key player, arranged a huge parliamentary lobby, with 4000 representatives from every part of the country, which called for sanctions against South Africa.

The Nineties

FW de Klerk announced the unbanning of the liberation organisations on 2 February 1990, and on 11 February Mandela walked out of prison in Cape Town. His freeing was greeted with spontaneous celebrations throughout the UK, with thousands descending on Trafalgar Square and other sites throughout the country.

The AAM was caught in a strange predicament: almost everything it had fought for was now a reality, and the movement had to re-assess its role and, indeed, its very reason for existence. Rather than dissolve itself, the AAM continued to monitor developments in South Africa. Membership numbers fell, but a core of activists remained to see through the last mile in the struggle against apartheid.

The AAM decided on three key issues: it would continue to call for sanctions until majority rule was a reality; it would encourage the creation of a climate conducive to negotiations; and it would only endorse one outcome – a united, non-racial South Africa.

Already, Thatcher was moving to undo the sanctions. On 2 February she announced that the ban on cultural, academic and scientific links would be relaxed, and on 10 February she declared that she would lift the voluntary bans on new investment and the promotion of tourism. The AAM stepped up its People’s Sanctions campaign, and worked with European groups to stop the European Community from lifting sanctions. The ANC called for sanctions to be maintained until a transitional executive council was in place, and the AAM endorsed the ANC’s call. However, there was confusion when the ANC allowed a South African rugby team to tour the UK in 1992.

In April 1990, convinced that FW de Klerk was trying to stall negotiations and renege on agreements, the AAM met with foreign secretary Douglas Hurd to draw attention to the continued imprisonment of hundreds of political prisoners, many of them on death row, but Hurd refused to intervene. The AAM initiated a mass letter-writing campaign, with letters being sent to De Klerk and Lynda Chalker.

The AAM was horrified when ‘Third Force’ violence spread from KwaZulu-Natal to Johannesburg. De Klerk, on his third visit to the UK in October 1990, was met by the AAM’s emergency campaign. Its letter to Thatcher, was headed: ‘Tell De Klerk: stop the violence and repression.’ When the AAM got news of the Boipotong Massacre, Huddleston demanded that the government consult with the European Union and the Commonwealth to find ways to monitor the violence. AAM protesters held a vigil outside South Africa House. Mike Terry and Huddleston flew to South Africa, and Huddleston addressed crowds at the funeral of the victims.

On his return, Huddleston organised an international hearing, where delegates from 27 countries heard eye-witness accounts of the killings. The British government changed its stance at the UN, and gave its support for UNSC resolution 772, which authorised the UN to send monitors to South Africa. Observer missions were then established by the OAU, the Commonwealth and the European Community.

The AAM’s last mass rally was held at Trafalgar Square on 20 June 1993, where Walter Sisulu demanded that an election date be announced. When the date was announced on 2 July 1993, Huddleston once again appealed to the OAU, the Commonwealth and the European Community to send observers to monitor the elections, and the subsequent deployment constituted ‘the world’s largest ever international election monitoring operation’, according to Gurney.

The AAM’s last campaign, ‘Countdown to Democracy’, launched in January 1994, appealed to Britons to donate money to the ANC, which had initiated a ‘votes for freedom’ appeal. Throughout the UK, people cast symbolic votes and donated money to the ANC, the trade unions alone raising £250,000.

On election day, 27 April 1994, the AAM witnessed hundreds of South Africans cast their vote at South Africa house, many of them activists in exile or ordinary South Africans living in the UK. When Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first president of the new, democratic South Africa on 10 May, a live video showing Mandela taking the oath of office was witnessed by the gathering at South Africa House, marking the close of a long chapter in international solidarity.

The AAM becomes ACTSA

At it last annual general conference, held on 29 October 1994, the AAM listened to an address by South Africa’s new justice minister, Dullah Omar, before the organisation was reborn as Action for Southern Africa, a body dedicated to supporting the eradication of the effects of apartheid and colonialism on the entire subcontinent.