Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu was born in Pretoria on 10 July in 1956. He was the second son of Martha Mahlangu. His father left him in 1962, and from then on only saw him infrequently. His mother was a domestic worker and took sole responsibility for his upbringing. He attended Mamelodi High School up to Standard 8, but did not complete his schooling as a result of the school’s closure due to ongoing riots.

He joined the African National Congress (ANC) in September 1976, and left the country to be trained as an Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) “The Spear of the Nation” soldier. The training was received in Angola and Mozambique and on 11 June 1977 he returned to South Africa as a cadre, heavily armed, through Swaziland to assist with student protests.

On 13 June 1977, Mahlangu and his companions, Mondy Johannes Motloung and George "Lucky" Mahlangu, were accosted by police in Goch Street, Johannesburg. “Lucky” Mahlangu managed to escape, however, in the ensuing gun battle two civilian men were killed and two wounded. Solomon Mahlangu and Motloung were arrested.

Solomon Mahlangu was tried from the 7th of November 1977 to the 1st of March 1978, for charges associated with the attacks in Goch Street in June 1977. He was therefore charged with two counts of murder and several charges under the Terrorism Act. Mahlangu pleaded not guilty to the charges. His council stated that he entered South Africa in June 1977 as part of a group of ten, bringing arms, ammunition, explosives and ANC pamphlets into the country.

The judge accepted that Motloung was responsible for the actual killings, but since he had been so brutally beaten during the course of his capture, he had suffered severe brain damage and was unfit to stand trial. However, as common purpose had been formed, Mahlangu was therefore found guilty on two counts of murder and three charges under the Terrorism Act. He was sentenced to death by hanging on 2 March 1978.

On 15 June 1978 Solomon Mahlangu was refused leave to appeal his sentence by the Rand Supreme Court, and on 24 July 1978 he was refused again in the Bloemfontein Appeal Court. Although various governments, the United Nations, international organizations, groups and prominent individuals attempted to intercede on his behalf, Mahlangu awaited his execution in Pretoria Central Prison, and died on 6 April 1979.

The execution provoked international protest and condemnation of South Africa’s internal policy. In fear of crowd reaction at the funeral the police decided to bury Mahlangu in Atteridgeville. On 6 April 1993 he was reinterred at the Mamelodi Cemetery, where a plaque states his supposed last words:

"My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Tell my people that I love them. They must continue the fight."

In 1993, the Solomon Mahlangu Square in Mamelodi was dedicated to his memory. The ANC hailed him as hero of the revolutionary struggle in South Africa, and subsequently named a school after him, in honour of his courage and dedication: The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO). He was awarded “The Order of Mendi for Bravery in Gold for bravery and sacrificing his life for freedom and democracy in South Africa” posthumously in 2005.

*Note: Sources differ as to the birthplace of Mahlangu, as other sources state he was born in Doornkop, Middelburg.

Early life and training in exile 1956 - 1976

Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu was born in Pretoria on 10 July in 1956. He was the second son of Martha Mahlangu. His father left the family in 1962, and from then on Mahlangu only saw him infrequently. His mother was a domestic worker and took sole responsibility for his upbringing. He attended Mamelodi High School and was in standard eight (grade 10) at the time of the 1976 Soweto uprisings against Bantu Education. The protests spread throughout the country, and after being recruited by Thomas Masuku, Mahlangu joined the protests in his area, Mamelodi, near Pretoria.

Shortly after the uprising Mahlangu left the country to join the African National Congress (ANC), to be trained as an Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) cadre. Mahlangu was part of a new generation of MK recruits dubbed the June 16 Detachment, as the group was made up mainly of students who were part of the student uprisings of 1976.

He left without informing his family, who thought he was still selling goods on trains and had ended up in Pietersburg. Mahlangu left a letter under his brother’s pillow:

“Boet Lucas, Boet Lucas, Boet Lucas, don’t look for me, I have left and you’ll never find me”.

Later, Temba Nkosi’s father, the young man Mahlangu left the country with, came to inform the family that their son had left to join the ANC in exile.

Mahlangu, Masuku, Temba Nkosi and Richard Chauke all left South Africa via Mozambique and spent six months at Xai Xai refugee camp. Later they were rescued and transported to an ANC training facility, called Engineering, in Angola. Mahlangu was reassigned to various cells within the training camp but he eventually joined a smaller unit of 10 men under Julius Mokoena, who reported to the commander in chief, Joe Modise. Amongst the 10 were George ‘Lucky’ Mahlangu and Mondy Motloung. The unit was trained at Funda Camp; they underwent crash courses in sabotage, military combat, scouting and political education.

The Goch Street shoot-out 1977

Goch Street, the site where the John Orr’s warehouse was located. Source: South African National Archives

Goch Street, the site where the John Orr’s warehouse was located. Source: South African National Archives

Mahlangu’s MK unit left Angola in mid-1977 on a mission to join student protests commemorating the June 16 Uprising and the police massacre that followed. They travelled through Mozambique to Namatswa on the Swaziland border, where Collin Ramusi met them. Ramusi drove them to a safe house in Mbabane, where they were briefed by General Siphiwe Nyanda and given suitcases filled with false bottoms containing pamphlets, guns and grenades. The packages in which cadres received their sabotage material were known as ‘Dead letter Boxes’ (DLBs). It was common for each unit to be split into cells of three cadres when travelling into South Africa. Mahlangu was assigned to a cell with Lucky and Motloung.

On 11 June 1977 their cell crossed the border into the South African town of Piet Retief. They moved around, staying at the homes of various family members and contacts. At each stop they hid parts of their DLBs, certain items were left for the use of other cadres who would pass through the area later, and others were to be used by local communities for the June 16 protests.

On 13 June 1977 the trio made their way to the Diagonal Street taxi rank in Johannesburg where they planned to catch a taxi to Soweto. As the first anniversary of the Soweto uprising was just three days away, police presence was strong and evident. A Black policeman on patrol noticed the trio entering a taxi with large bags and approached them. The policeman said ‘laat ek sien wat het julle daar!’ (Let me see what you have there). The policeman grabbed a bag and a hand grenade and AK-47 rifle fell out, with the policeman running for cover. The trio panicked and fled from the taxi, disappearing into the crowd. Lucky ran in the direction of Park station and managed to elude capture.

Mahlangu and Motloung ran towards Fordsburg along Jeppe Street, not realising that they were running towards John Vorster Square, the most notorious police station in the country. On the way Motloung got into a tug-of-war with an off-duty policeman. He managed to get away, but the policeman shot at the running pair, hitting Mahlangu in the ankle. The pair kept running, turning left into Goch Street. Running slightly ahead of Motloung, Mahlangu ran into John Orr’s warehouse, where he took cover. Desperately seeking Mahlangu, a panicked Motloung entered the warehouse and fired shots, killing two John Orr’s employees.

Within minutes police surrounded the entire area. Mahlangu and Motloung were beaten by onlookers and the police, and arrested and detained at the nearby John Vorster Square Prison. The media quickly caught wind of the shooting, printing headlines such as ‘Terrorists in the country’.

The Trial 1977 - 1978

Mahlangu and Motloung were brutally abused while in police custody. The police detained them under the 90-day Detention Law giving the state time to fabricate a case against the pair. Before the trial could commence Motloung was so badly beaten that he sustained severe brain damage. Clinical psychologist Annah Venter declared Motloung unfit to stand trial.

Still from SAPS film of Solomon Mahlangu being escorted by policeman from the courtroom, 1978. Source: South African National Repository

Still from SAPS film of Solomon Mahlangu being escorted by policeman from the courtroom, 1978. Source: South African National Repository

Solomon’s mother and brother – not knowing what was happening – were taken to see him. Solomon and his mother stood in silence looking at each other, and eventually Solomon asked his mother how the family was doing, she answered that they were all right, but after another period of silence she broke into a flood of tears. Solomon then asked his mother; ‘Why are you crying in front of these dogs”¦ I don’t care what they do to me. And if they spill my blood, maybe it will give birth to other Solomons.’

Mahlangu’s trial started on 7 November 1977 and ended on 1 March 1978. Martha Mahlangu and her children sought the legal expertise of Advocate Ismail Ayob & Partners to defend her son. The defence team included Ismail Mohammed, Clifford Mailer and Priscilla Jana. Mahlangu was charged with two counts of murder, two of attempted murder and several charges of sabotage under the Terrorism Act. He pleaded not guilty to all charges. Although Motloung was the one who fired the shots that killed the two civilians and wounded two others, the Prosecution argued that under the law of Common Purpose, Mahlangu shared intent with Motloung and George ‘Lucky’ Mahlangu, making him guilty of murder whether or not he pulled the trigger.

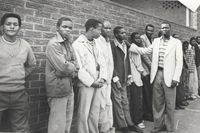

Man identifies Mondy Motloung in a line-up at Middleburg Police Station. Source: South African National Archive

Man identifies Mondy Motloung in a line-up at Middleburg Police Station. Source: South African National Archive

The Common Purpose law argues that all parties together committing a crime should face the same consequences regardless of whether they carried out the same acts or knew of each other’s intent.

For the acts that Mahlangu had in fact committed, he should have received a maximum of five years’ imprisonment. The State demanded the death penalty and the prosecution got its way when he was sentenced to death by hanging on 2 March 1978. On 15 June 1978 the Rand Supreme Court refused Mahlangu leave to appeal his sentence, and on 24 July 1978 the Bloemfontein Appeal Court again turned him down. Mahlangu awaited his execution in Pretoria Central Prison.

Execution and Reactions 1978 -

Although various governments, the United Nations, international organisations, groups and prominent individuals attempted to intercede on his behalf, Solomon ‘Kalushi’ Mahlangu was hanged at the Pretoria Central Prison on 6 April 1979. The day of execution, observers believe, was deliberately chosen to coincide with the 327thanniversary of Jan van Riebeck’s arrival at the Cape in 1652.

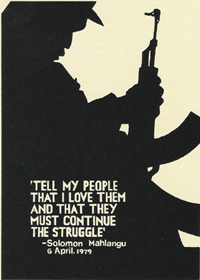

In apparent defiance of Prime Minister PW Botha, Mahlangu’s last message was inspirational. Before he was executed, Mahlangu said: ‘My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Tell my people that I love them. They must continue the fight.’

The police decided to bury Mahlangu in Atteridgeville, afraid that there would be violent protests during the funeral.

The 1976 generation of MK combatants

Within a few months of his execution, from 1979 to 1983, units of the June 16 Detachment mounted a series of attacks inside South Africa. The Silverton Siege occurred in January 1980, during an attack carried out by units of the June 16 Detachment known as TUM and G5. Other TUM units carried out attacks on police stations in Soweto, Wonderboom in Pretoria and Soekmekaar.

Solomon Mahlangu: designed by Judy Seidman with Medu Art Ensemble, silkscreen, Gaborone, 1982

Solomon Mahlangu: designed by Judy Seidman with Medu Art Ensemble, silkscreen, Gaborone, 1982

Those behind the attacks in Soekmekaar and Wonderboom were charged in what became known as the Silverton Trial, and were sentenced to between 10 and 20 years in prison. Marcus Motaung and two of his companions, charged with attacks on police stations in Soweto – including Orlando – were sent to the gallows in 1983.

International and National protests

Besides the protests and appeals from across the world directly related to Mahlangu’s execution, various bodies became increasingly vocal about the death sentence, especially political executions.

Towards negotiation and reconciliation

The Law Today

Mahlangu, among others, was charged under provisions of the Terrorism Act of 1967. The Act was enacted after the Rivonia Trial, with the aim of tightening security legislation and preventing a recurrence of acts of sabotage reminiscent of those carried out in 1961. Another law that was passed and directly affected Mahlangu was the Criminal Procedure Act of 1967 – the law provided for stiffer sentences for murder with aggravating circumstances.

Over and above all of these laws, it was ‘the principle of common purpose’ that most affected Mahlangu and many others in political trials. The legal principle originates in English law, the general idea being that when a group of people embark on an unlawful or dangerous activity and someone gets hurt, all the participants may be found jointly liable even if it is not clear precisely who caused the harm. It was this principle that alerted many protesters to the injustice of political assassination verdicts.

Between 1990 and 1993 numerous political formations and the Apartheid government were involved in negotiations. Initial interactions led to the formation of CODESA I and II, culminating in South Africa’s first democratic elections of 1994 and the birth of the new constitution.

Human Rights and the Bill of Rights, including the right of association, are guaranteed in the new constitution. It is inconceivable that acts of political dissent can be considered ‘common law’ crimes today. The principle of common purpose cannot be applied in a legal system that is informed by the desire to uphold human rights.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Solomon Mahlangu’s mother, Martha Mahlangu, represented the family at the TRC hearings on 3 May 1996. She told the TRC that she had heard news over the radio about ‘terrorists’ who had shot and killed White people in Johannesburg. She had no idea that Solomon was involved until the police came to search her home looking for evidence implicating him that could help with their investigation. She then pointed out that she had not been allowed to see him until after his trial.

Mrs Seroke, leading Mrs Mahlangu during her testimony, wanted to establish if Mrs Mahlangu knew that Solomon’s actions had unjustly brought the death penalty the court handed down to him. Mrs Mahlangu indicated that she was not aware of the technicalities of the trial. Asked what she expected of the TRC, she said that it was at the Commission’s discretion to decide what had to be done to establish the truth. She said she would welcome any assistance. During an interview years after the TRC hearing, she said she found it difficult to forget what the apartheid courts had done to her family and she carried with her the pain of losing her son every day.

‘My son had aspirations of becoming a school teacher”¦ He was very conscientious and humble. He stood firm and unshaken in his beliefs. Now, in my old age, I miss him even more,’ Martha Mahlangu quoted in the Mail & Guardian, 1999

Remembering Solomon Mahlangu

On 6 April 1993, Solomon Mahlangu’s body was reinterred at the Mamelodi Cemetery, where a plaque states his last words:‘My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Tell my people that I love them. They must continue the fight.’

Recently, more tributes have been paid in Mahlangu’s memory. A statue of Mahlangu was unveiled in 2005 in Mamelodi and a stamp bearing an image of Mahlangu was unveiled by the South African Post Office to mark the 30th commemoration of his execution on 6 April 2009.

Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO)

The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College was established on a dilapidated sisal farm donated by the Tanzanian government to the African National Congress (ANC) in 1979. The 5000 hectare piece of land was located in the city of Morogoro, Tanzania. The area is known as Mazimbu.

Mr Reddy Mampane, was deployed by the ANC in 1973 to hold discussions with authorities in Tanzania when the ANC sought means to accommodate an ever increasing influx of youth who were fleeing the apartheid regime in South Africa with the objective of joining the liberation effort of South Africa through the ANC. In 1975 led by Anna Abdullah, the Tanzanian government donated this old Sisal farm to the ANC. ANC veterans of the highest calibre testify that when this land was just bush when it was donated. It was hard to see past the high weeds that infested the land. Denis Oswald, an activists who had just completed his studies on architecture through an ANC scholarship was unperturbed by the sprawling bush and saw opportunity.

Driven by a strong vision and through the sheer initiative, perseverance, co-operation between leaders, ANC members and most importantly the future students themselves, trenches where dug and the foundations where laid towards opening the doors of learning. In 1977, whilst work was ensuing in Mazimbu, the apartheid regime captured the 21 year old Solomon Mahlangu which resulted in an international for his clemency throughout his 2 year trial for a crime he had not committed.

In 1979, as the first buildings were being completed, amidst international outcries from luminaries such as E.S Reddy who chaired the anti-Apartheid Committee of the United Nations, Father Trevor Huddleston, former United States President Jimmy Carter, former French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and many other governments, Solomon Mahlangu was sentenced to death.

On April 6 1979, the same date that Jan Van Riebeeck had first set foot on South African soil, Solomon Mahlangu was sent to the gallows.

The late ANC President OR Tambo, delivering a speech in Asia called the spirit of Bundung said of Solomon Mahlangu: “..In his brief but full life Solomon Mahlangu towered like a colossus, unbroken and unbreakable, over the fascist lair. He, on whom our people have bestowed accolades worthy of the hero-combatant that he is, has been hanged in Pretoria like a common murderer. Alone the hangmen buried Solomon, bound by a forbidding oath that his grave shall remain forever a secret, because, in his death the spirit of Solomon Mahlangu towers still like a colossus, unbroken and unbreakable, over the fascist lair”¦”

It is this commitment to the liberation of South Africa and his unbroken and unbreakable spirit that amongst other factors characterized the essence of the effort of those who were building in Mazimbu and that encapsulated the vision of what was being built in Mazimbu.

On completion of the school, it was decided that in remembrance and the spirit of Solomon Mahlangu, it was apt to name this historic institution that was also a beacon of international solidarity and collaboration as the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO).