Early Years

Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela was born, the fifth of nine children, in the village of Mbongweni, Bizana, in the Transkei on 26 September 1936. During her infant years her father, Columbus, was a local history teacher. In later years he was the minister of the Transkei Governments’ Forestry and Agriculture Department during Kaizer Matanzima's rule. Her mother, Nomathamsanqa Mzaidume (Gertrude), was a science teacher.[i]

Her parents desperately wished Winnie had been born a boy and growing up, Winnie took pains to fulfil the role of tomboy by playing with the other boys in her peer group, practising stick fighting and setting traps for animals. [ii] Once, while quarrelling with her younger sister, Princess, Winnie fashioned a knuckleduster out of a nail and a baking powder tin and accidentally struck her sister across the face while aiming for her arm. It was one of many instances for which her mother administered a hefty beating.[iii]

As a young girl, Winnie’s family moved around within the former Transkei, due to her father’s work. She attended primary school in Bizana but when she was nine years old, the family moved to eMbongweni, where as well as attending school, Winnie would help her father to labour on the farm. This helped create a closer bond with her father, who was known for his aloofness despite wielding a great love for his children. Colombus, to all intents and purposes, was a proud man who greatly valued educated and who saw the importance of educating his children about their Pondo roots as well as traditional academic subjects.

When Winnie was still young, two tragic events hit. Firstly her elder sister, Vuyelwa, contracted tuberculosis and died – an event which shook Winnie’s belief in the God her mother had ardently prayed to during her daughter’s demise. Secondly, soon after her sister’s death, Winnie’s mother also developed the disease and died. However, shortly before her mother passed away she gave birth to a baby boy, whom Winnie took responsibility for during her mother’s incapacitation, and after her death.

Portrait of a young Winnie Image source

Portrait of a young Winnie Image source

Early Experiences of Apartheid

In 1945, when she was only nine years old, Winnie had her first conscious experience of what the strictures and injustices of racism and apartheid meant in South Africa. News had just arrived in Bizana that the Second World War had ended, and celebrations had been scheduled. Along with her siblings, Winnie begged their father to attend, and eventually he acquiesced to their demand. However, upon arriving at the town hall, it was discovered that these celebrations were “for whites only” and the children were forced to remain outside with their father while the white population enjoyed the merriment within.[iv] The obvious injustice struck a deep blow for Winnie, and thereafter she grew increasingly sensitised to the inequality of the world around her.

This incident was followed by another, equally formative one. In Bizana, there was a large Black population, but all shops and services were owned by Whites. One day, Winnie recalls seeing a scene in a shop with her father, whereby a Black man was squatting on his haunches and breaking off pieces off bread to feed to his wife while she breastfed their baby. All of a sudden a White youth – the son of the shop owners, came charging towards them and yelling that he wouldn’t have kaffirs making a mess in his store. He kicked at them and their food and forced them out of the shop. Winnie watched the scene dumbstruck. She could not understand how this man could allow himself to be treated thusly, or why her father, who was such a staunch moralist, would not intervene where his morality so obviously demanded that he should. In time she came to understand that her father’s involvement would likely only have made the situation worse, and moreover, that a byproduct of Apartheid was that from an early age Black children became accustomed to seeing their parents humiliated without any attempt to protest in defence of themselves.[v]

Luckily for Winnie, Bantu education – the hated Apartheid policy of introducing separate education syllabi for Whites and Blacks – was only introduced in the early 1950s. Therefore she was able to benefit from an education that was on par with her White peers at the time. She passed her junior certificate (Standard 8) with distinction and then went on to study at Shawsbury, a Methodist mission school at Qumbu. It was there that she matriculated and distinguished herself as a person with exceptional leadership qualities. It was also there, under the tutelage of teachers who were all Fort Hare graduates, that she began to become more politicised. Due to financial constraints, Winnie’s sister, Nancy, to whom Winnie was close, dropped out of school and worked casual jobs to ensure that Winnie’s education could continue.[vi]

When Winnie returned from Shawsbury with a first-class pass, she discovered that her father had remarried. His new wife was a woman by the name of Hilda Nophikela, whom all of the Midikizela children welcomed into the family fold, especially Winnie.

Move to Johannesburg

In 1953, upon her father’s advice, Winnie was admitted to the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work in Johannesburg, where Nelson Mandela (who was already gaining national renown), was the patron.[vii] It was the first time she left the Transkei and a formative moment in her life. It was in Johannesburg that she saw the full effects of Apartheid on a daily basis, but also where she discovered her love of fashion, dancing and the city. It was only after a few months of living in Johannesburg that Winnie first went to Soweto.

She completed her degree in social work in 1955, finishing at the top of her class, and was offered a scholarship for further study in the USA. However, soon after receiving the scholarship offer, she was offered the position of medical social worker at the Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg, making her the first qualified, Black member of staff to fill that post. Following an agonising decision about whether to leave and further her academic career in the USA, or to stay and pursue her dream of becoming a social worker in South Africa, she decided to remain in South Africa.

Whilst working at the hospital, Winnie’s interest in national politics continued to grow. She moved into one of the hostels connected to the hospital and found that she was sharing a dormitory with Adelaide Tsukudu, the future wife of former African National Congress (ANC) president, Oliver Tambo. Indeed, Adelaide would confide in Winnie while they were in bed at night about the brilliant lawyer she would soon marry, and his legal partner, Nelson Mandela. It also transpired that Tambo happened to be from Bizana, like Winnie, making them members of the same extended family.

It is worth reiterating that Winnie was already politically interested and involved in activism long before she met her future husband. She was particularly affected by the research she had carried out in Alexandra Township as a social worker to establish the rate of infantile mortality, which stood at 10 deaths for every 1,000 births.

During her time at Baragwanath, Winnie’s reputation began to grow, with stories and photographs about her appearing in newspapers, acknowleging the achievement of this girl from Pondoland who came to Johannesburg and looked to be making a name for herself.

Until 1957, Winnie had been fairly romantically uninvolved. However, in that year she met with Barney Sampson, a “gallant, fun-loving man”[viii] of whom Winnie eventually grew tired due to his apoliticism and submissive attitube to white domination. Soon afterwards, Winnie was also courted by the future chief of the Transkei, and her father’s future boss, Kaiser Matanzima, whom happened to visit Baragwanath hospital as a disitinguised visitor that year. It was a relationship that was never to be, however, because she was soon to fall in love with Matanzima’s childhood acquaintance and relative, Nelson Mandela.

Marriage to Nelson

Winnie was twenty two when she met Nelson, and he was sixteen years her senior. He was already a famous anti-apartheid figure and one of the key defendants in the Treason Trial, which had commenced the year before, in 1956. From the very beginning, Nelson was ensconced in the Liberation Struggle, and the parameters of their romance were set by his commitment to political change. On March 10 1957, Nelson asked Winnie to marry him and they celebrated their engagment together in Johannesburg on 25 May 1958.

Despite government restrictions on the movements of Treason Trial defendents, Winnie and Nelson got married on 14 June 1958, in Bizana. The celebration caught the national interest and was reported in publications such as Drum Magazine and the Golden City Post.

Their marriage was to prove both robust and fraught. Winnie quickly discovered that life married to one of Apartheid’s most famous opponents was a lonely one. Her husband was incessently busy with ANC meetings, legal cases and the Treason Trial. The Mandela residence was also a site for frequent police raids, during which policemen would awaken the household with loud banging on the doors in the early morning and set to turning the whole house upside down. Added to the turbulence of their early married life, in July, Winnie found out she was pregnant with her first child.

In October 1958, Winnie took part in a mass action which mobilised women to protest against the Apartheid government’s infamous pass laws. This protest in Johannesburg followed a similar action that had taken palce in Pretoria in August 1956.[ix] The Johannesburg protest was organised by the president of the ANC Women’s League, Lilian Ngoyi and Albertina Sisulu, amongst others. In fact, Winnie travelled with Albertina from Phefeni station in Orlando to the city centre where the protest was taking place. During the protest, the police arrested 1000 women.

A decision was taken by the arrested women not to apply for immediate bail, but to rather spend two weeks in prison as a sign of further protsest. During these weeks, the pregnant Winnie saw first hand the squalid conditions of South African prisons, and her commitment to the struggle only intensified. Eventually, Nelson and Oliver Tambo were called to arrange their bail, and the ANC raised money to pay the convicted women’s fines. It was an event which took Winnie out of her husband’s considerable shadow in eyes of the public, but also one which alerted national security to her potency as a voice of political dissent - independent of her famous husband. Shortly afterwards she was sacked from her post at Baragwanath hospital. Following the trauma of incarceration, on February 4 1959 Winnie gave birth to a daughter she named Zenani.

On March 30 1961, nine days after the police murdered sixty-nine people during a Pan African Congress (PAC) anti-pass demonstration at Sharpeville, a police raid on the Mandela home saw Nelson arrested and Winnie left by herself, in what would become her overarching experience of marriage.

Winnie’s Influences

Winnie had a few influential presences in her life: chief amongst them were Lillian Ngoyi, who, along with Helen Joseph, were the only two women accused in the Treason Trial; Albertina Sisulu; Florence Matomela; Frances Baard; Kate Molale; Ruth Mompati; Hilda Bernstein (who was the first Communist Party member to serve on the Johannesburg Council in the 1940s); and Ruth First. These were people who Winnie was able to consider not only as sources of inspiration, but as trusted confidantes. This is significant, because as Winnie’s struggle against government continued, her inner circle became consistantly infiltrated by people who would gain her trust as allies, only to reveal themselves later as spies.[x] As Nelson spent increasing amounts of time in police custody or underground, the number of unsettling relationships Winnie established with people who would turn out to be police informants also seemed to increase. As Bezdrob has written about Johannesburg at the time, it was “a cesspool of informers” and unfortunately for Winnie, she appeared to be surrounded by spies.[xi]

Bantu Authorities and Rift with Colombus

Conflict occurred in the family when the Apartheid government introduced the Bantu Authorities Act in 1951. Kaizer Matanzima, her former suitor, had sided with the government and fought the opposition to the government’s transparently divide-and-rule policy. A body of Pondo elders, referred to as Intaba, opposed the Bantu Authorities and waged a resistance that swept Winnie’s family up into the turmoil. One night during a raid on her family home (specifically targeting her father, Colombus, due to his reluctance to donate his buses to their cause) Intaba rebels entered his house and badly assaulted his wife before burning down the hut where they lived. Winnie’s stepmother survived the attack, but was paralysed from the waist down and died soon after. Despite this event, Colombus sided unequivically with Kaizer Matanzima and was subsequently rewarded with a cabinet position in the Transkei homeland looking after agriculture. This was a huge betrayal for Winnie as it was tantamount to siding with the Apartheid government. Winnie’s other relatives joined the resistance, thus her family was cleft in two.[xii]

Treason Trial

On 29 March 1961 the verdict from the Treason Trial, delivered by Justice Rumpff, declared all of the accused ‘not guilty.’ This event followed quickly after another, equally joyful happening, which was the birth of the Mandela’s second daughter, Zindziswa on 23 December 1960, who was named after the daughter of Samuel Mqhayi, the famous Xhosa poet. However, Winnie’s joy at having a second child and seeing her husband’s name cleared was immediately tempered by the news that the ANC executive required him to go into hiding. Nelson had not discussed this with his wife, simply taking the support of his family for granted. Such was life married to the leader of a revolutionary movement.

Winnie’s married life to Nelson while he was in hiding was unusual, to say the least. She would meet him clandestinely in highly covert places; often with Nelson in thick disguise. This was the ‘Black Pimpernel’ phase of Nelson’s life, and Winnie had little choice but to fit in around his clandestine activities.[xiii] Their most intimate and prolonged encounters occurred at the Lilliesleaf farm in Rivonia.

On Sunday 5 August 1961, the police finally apprehended Nelson while he was driving from Durban to Johannesburg. It was to be the beginning of his 27 year detention and another event that caused an irrevocable change to the direction of Winnie’s life.

With Nelson in jail and in virtual isolation for the first four months of his detention, the police, sensing Winnie’s potential to carry the cause, slapped her with a banning order on 28 December 1962. This restricted her movements to the magisterial district of Johannesburg; prohibited her from entering any educational premises and barred her from attending or addressing any meetings or gatherings where more than two people were present. Moreover, the banning order also stipulated that media outlets were no longer permitted to quote anything she said, effectively gagging her voice too.

During this time, Winnie also became conscious of certain Janus-faced individuals who, under the guise of friendship secretly betrayed her secrets to the police. People such as the journalist Gordon Winter were fully fledged agents of the state who took advantage of Winnie’s isolation to infiltrate her life and offer their friendship and support, all the while daily betraying her confidence to Apartheid officials. This was also a time of increased police harassment and intimidation, with regular aggressive raids occurring on her house. To make matters worse, there also occurred the repossession of all of her furniture after Nelson had neglected to make provision for regular hire purchase payments following his arrest.

‘Inside Boss,’ the expose written in 1981 by former BOSS spy, Gordon Winter, just one of many people Winnie put her trust in, only to be badly betrayed. Image source

‘Inside Boss,’ the expose written in 1981 by former BOSS spy, Gordon Winter, just one of many people Winnie put her trust in, only to be badly betrayed. Image source

At the end of May 1963, Mandela was transferred without warning to Robben Island. Ironically, once absorbed into the prison system proper, Mandela, who was so fluent in the laws and strictures of the country, found himself much less vulnerable to abuse than Winnie found herself on the outside.[xiv] Whereas prison for all its despicable features was governed by clear rules and structures, outside of prison Winnie found herself at the mercy of unpredictable and chaotic forces, which she was ill-equipped to navigate. In June of that year she was first permitted to visit her husband in jail. She travelled 1400 kilometres from Johannesburg to Cape Town for the purpose, before a 10 kilometre journey over choppy seas to Robben Island. Once there the couple were allowed to meet for just 30 minutes, separated by dual wire mesh, no seats, and a security detail in easy listening distance. They were not permitted to speak to one another in Xhosa; only English or Afrikaans.

Nelson was unexpectedly moved from Robben Island back to Pretoria barely a month after his initial transfer. The reason for the move soon became clear, however, as his close colleagues within the ANC had been arrested in a swoop on the Lilliesleaf farm. Nelson was to be tried with them in the infamous Rivonia Trial, in which he and his co-accused escaped the death penalty, but were handed life imprisonment on Robben Island instead.

With her husband in jail, the authorities increased the pressure to make Winnie’s life as difficult as possible, with her children Zenani and Zindziswa particularly targeted. On numerous occasions Winnie enrolled them into schools, only for the security police to find out and insist that the schools have them expelled.[xv] This was in addition to the continued raids on her house; her banning order and frequent last minute refusals to visit her husband in jail.

A flavour of the harassment and trauma of a typical raid is summed up by Winnie herself:

“…that midnight knock when all about you is quiet. It means those blinding torches shone simultaneously through every window of your house before the door is kicked open. It means the exclusive right the security branch have to read each and every letter in the house. It means paging through each and every book on your shelves, lifting carpets, looking under beds, lifting sleeping children from mattresses and looking under the sheets. It means tasting your sugar, your mealie meal and every spice on your kitchen shelf. Unpacking all your clothing and going through each pocket. Ultimately it means your seizure at dawn, dragged away from little children screaming and clinging to your skirt, imploring the white man dragging Mummy away to leave her alone.”[xvi]

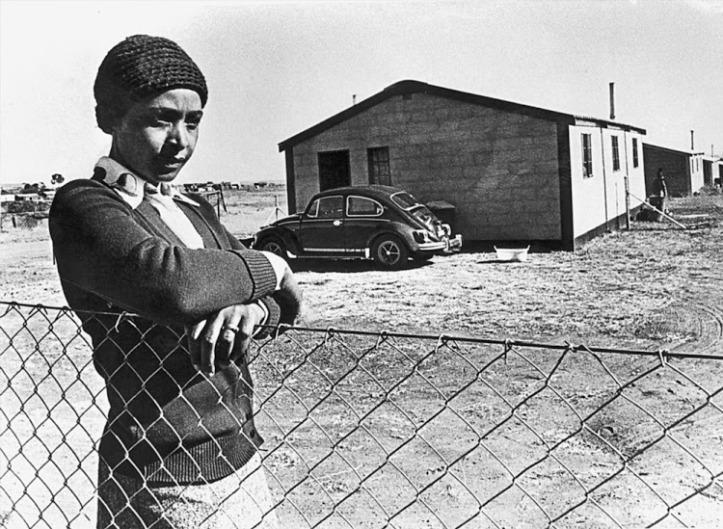

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela during her exile in Brandfort in 1977. Image: Gallo Images/ Avusa Archives/ Peter Magubane Image source

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela during her exile in Brandfort in 1977. Image: Gallo Images/ Avusa Archives/ Peter Magubane Image source

Banning Orders and Jail

In 1965, a new and more severe banning order was handed to Winnie. Previously her banning order had limited her movements from ‘dusk to dawn’ but her new banning order barred her from moving anywhere other than her neighbourhood of Orlando West. This had several ramifications, including the necessity for her to give up her job as a social worker. Subsequently, she was hounded out of job after job with the police approaching anyone bold enough to give her employment be it a dry cleaning temp or a clerkship, and insist that by some mechanism they fire her.[xvii] Due to her continued struggles and that of finding her daughters a school, Winnie eventually sent them away to Swaziland and with the help of Lady Birley (wife of Sir Robert Birley, an ex-headmaster of Eton College) and Helen Joseph, she was able to enrol them at Waterford Kamhlaba private school.

Meanwhile in South Africa, Winnie continued to keep active. From her highly restricted position, she organised assistance for political prisoners. On the night of 12 May 1969 Winnie awoke to the familiar sounds of a police raid. Her children were home for the school holidays and the police made a particularly thorough investigation of everything in the house. After ransacking the property, they tore Winnie away from her daughters and bundled her into a police van. She had just fallen foul of Prime Minister John Vorster’s1967 Terrorism Act, No 83, which allowed the arrest of anyone perceived to be endangering the maintenance of law and order. It stipulated that anyone could be arrested without warrant, detained for an indefinite period of time, interrogated and kept in solitary confinement without access to a lawyer or a relative.

Winnie was kept in solitary confinement for seventeen months. For the first 200 days, she had no formal contact with another human being at all aside from her interrogators, amongst whom was a certain Major Theunis Jacobus Swanepoel; a notorious torturer.[xviii]The only items in her concrete cell were three thin bug-infested and urine-stained blankets, a plastic water bottle, a mug and a sanitary bucket without a handle. The only other feature of her confines was a bare electric light bulb, which burned constantly and robbed her of any sense of night or day.

During her interrogation, Winnie was kept awake for five days and five nights without respite in an attempt to break her will. Major Swanepoel played ‘bad cop’ to another officer’s ‘good cop,’ and together they pushed her relentlessly to provide information about the ANC and her husband. After five days of resistance, under every kind of coercion imaginable, the interrogation team brought a prisoner into the adjacent interview room and began torturing him. Winnie’s interrogators made it plain to her that her silence was causing unnecessary distress to others fighting for the cause, and eventually, her will broken, she acquiesced to tell them whatever they wished to hear.

On 1 December 1969, Winnie’s trial finally began. Winnie and her co-accused were represented by Joel Carlson, an old friend of Winnie and Nelson’s, and a well respected human rights lawyer. After many complications, Winnie’s release was finally secured. She had spent a total of seventeen months in prison with thirteen of those in solitary confinement, and nothing in the way of a conviction by the end of it.

Winnie’s first banning order expired while she was in jail. However, almost immediately upon being released she was served with another, lasting five years. This, more stringent restriction forbade her from leaving the house between 6pm and 6am and made it virtually impossible to see her husband on Robben Island. Before the second banning order took effect, however, Winnie travelled to the Transkei to see her father. Since their last meeting, Colombus had both aged visibly and become disillusioned with the state of the so-called ‘independent’ homeland.[ix]It had become clear to him that the homeland system was little more than a ruse to prevent Black South Africans from claiming full political rights in the country.

Despite the banning order, Winnie did in fact manage to visit Nelson again in prison. However, a half hour meeting through glass, observed and recorded by security police and subject to extreme self censoring was a distinctly unsatisfactory experience. Meanwhile, Winnie’s life outside of jail took an almost opposite turn to her husband’s. While Nelson and his ANC cadres on Robben Island accommodated themselves to being politically inert and concentrated their efforts on intellectual pursuits, Winnie found herself at the coalface of the struggle. The police raids were relentless, with intrusions into her home sometimes happening up to four times a day. Her house was routinely burgled, vandalised and even bombed. During this time, with her husband in jail and the ANC in the back foot, Winnie became something of a lightning rod for South Africa’s disenfranchised youth. To the Apartheid regime she became a significant political figure in her own right, as opposed to merely being the feisty wife of Nelson Mandela.

Up until the 1970s, the years of constant police harassment, jail time and intimidation had done absolutely nothing to quash Winnie’s revolutionary spirit; indeed, her conviction had only become stronger. Her message to the authorities was clear: “you cannot intimidate people like me anymore.”[xx]

In May 1973 Winnie was arrested again, this time for meeting with another banned person, her good friend and photographer for Drum magazine, Peter Magubane. She was handed a twelve month sentence to be served at Kroonstad’s women’s prison, however, this imprisonment was much less arduous than her previous incarceration and Winnie was released after six months. Winnie’s banning order expired in September 1975 and to her great surprise, was not immediately renewed.

Soweto Uprising and another Banning Order

By the mid 1970s, unrest amongst the South African youth had become increasingly volatile. Steve Biko had founded the Black Consciousness Movement in 1969 as a riposte to what he saw as unhelpful white liberal paternalism. The formation of the all-black South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) followed soon thereafter. The struggle for liberation in South Africa was increasingly being taken up the country’s youth and Winnie found herself settling into a new role to as the symbolic mother to this burgeoning student movement. In May 1976, just a few weeks before the famous student uprising in Soweto, Winnie along with Dr Nthatho Motlana helped to establish the Soweto Parents’ Association. In the weeks that followed the violence of June 16, Winnie and Dr Motlana had their hands full attending to youth and parents who had been arrested, injured or killed in the riots. The police attempted to pin responsibility for inciting the violence on Winnie herself, but regardless of how influential she might have been, Winnie’s influence alone could never explain the levels of anger amongst South Africa’s youth at that time.

Nonetheless, a simple scapegoat had to be found for the Soweto uprising and Winnie fit the bill. Once again she was detained. The police held her in custody for five months, eventually releasing her in December 1976 without charge. In January 1977, she was served with a fresh five year banning order.

Brandfort: a Banishment

There was, in fact, a far graver fate awaiting Winnie in 1977: in the early hours of the morning on May 15, a police contingent arrived at her doorstep to take her away to the station. Over the coming hours it transpired what the police had in store. On instruction from the government, the police were instigating Winnie’s domestic exile to a dusty town in the middle of the Free State, a place that would keep her for the next eight years of her life.

Brandfort lies around 400 kilometres south-west of Johannesburg and 50 kilometres north of Bloemfontein. Prior to her arrival in Phathakahle, the township there, the Department of Bantu Affairs had informed locals that a dangerous female – indeed, a terrorist – would be moving there and that they should avoid contact with her at all costs.[xxi]

To all intents and purposes Winnie’s banishment to Brandfort backfired. Instead of being demoralised by her isolation and the endemic racism of local shop-owners, Winnie continued much as before, flouting racist Apartheid legislation and dumbfounding conservatives with her audacity not to be cowed by unjust segregationist laws. Opinion polls taken during her first two years in Brandfort showed that she was seen to be the second most important political figure in the country after Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. Part of what kept Winnie motivated was her exceptional ability not to become demoralised and her inexhaustible tenacity to keep busy. While she was living out her banishment she established a local gardening collective; a soup kitchen; a mobile health unit; a day care centre; an organisation for orphans and juvenile delinquents and a sewing club.

After spending eight years in this backwater and in the midst of growing urban turmoil, Winnie’s banishment finally came to an end in 1986. She was at last free to return home to her house at 8115, Vilakazi Street, Orlando West.

States of Emergency and Mandela United Football Club

When Winnie returned to Johannesburg, the place she had come to identify as home, in 1986, she found it was a changed and more dangerous place than the one she had left behind. In 1985 Oliver Tambo, from his position in exile, had made a call to all South Africans to “make the country ungovernable” and people had heeded his call in droves.[xxii] The youth were running riot and the government’s imposition of a series of states of emergency had done nothing to quell the resistance.

Nonetheless, shortly after returning home, Winnie again set to doing what she had always done and looked for ways to help those she saw as vulnerable. To this end, Winnie established a place for disenfranchised youth to feel at home, organise, and socialise. This informal grouping of youngsters became known as the Mandela United Football Club (MUFC). There already existed in Soweto a Sisulu Football Club and it was therefore not an unusual moniker for the group to adopt. As it transpired, football was but one aspect of these groups’ vigilante activities and for MUFC, it would unfortunately be the last thing for which they were remembered.

During the long years that Nelson had been in jail and Winnie had been struggling by herself, the couple had moved in starkly opposite directions. Whilst Nelson and his Robben Island coterie had become more academic and statesman-like during their years cut-off from grassroots politics, Winnie on the other hand was forced to become a soldier on the ground. During her decades of police intimidation and harassment; her emotional brutalisation (having had her family torn apart and her closest friends betray her); and her physical imprisonment and banishment, Winnie had developed combative defences against a world that was unfailingly hostile. Since the latter stages of her exile, rumours had begun to circulate about Winnie’s increasingly erratic behaviour; her recourse to drink and her occasional bouts of violent behaviour. Once established in Soweto, these rumours refused to dissipate and her frequent public appearances in khaki uniform did little to quell speculation that her approach to liberation was becoming increasingly military driven and violent.

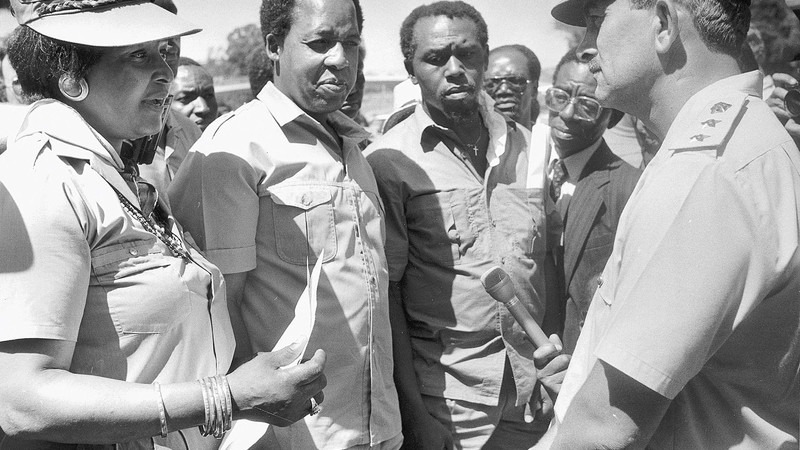

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Chris Hani and Tokyo Sexwale present at a rally in South Africa Image source

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Chris Hani and Tokyo Sexwale present at a rally in South Africa Image source

On April 13 in Munsieville, Winnie gave a speech that would become immediately infamous. Addressing a crowd of listeners, she declared that “together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this country.”[xxiii] This speech that appeared to overtly endorse the practice of necklacing was highly inflammatory and the media outcry against her was profound. However, in light of her enormous sacrifices to the cause, the ANC’s response was muted at best – this, despite the fact that behind closed doors there were murmurs amongst the organisation’s top brass that Winnie had become a liability.[xxiv]

Winnie Mandela, wearing her khaki slacks, helps bereaved comrades carry the coffin of an Apartheid victim. Image source

Winnie Mandela, wearing her khaki slacks, helps bereaved comrades carry the coffin of an Apartheid victim. Image source

As events in South Africa began to reach fever pitch in the late 1980s, with international calls for Nelson’s release resulting in massive pressure on the Apartheid government, life on the ground was more precarious and dangerous than ever. Despite the government making grand concessions by releasing top ANC members such as Govan Mbeki at the end of 1987; in the townships, murder, disorder and civil unrest were the order of the day. Furthermore, in Soweto the MUFC were quickly gaining a reputation for operating with impunity as a kind of vigilante mafia under the tutelage of their coach, Jerry Richardson, who later revealed himself to have been a police informer during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).[xxv][xxvi]

Joyce Mananki Seipei and Jerry Richardson, Johannesburg, 1997. Photographer Jillian Edelstein Image source

Joyce Mananki Seipei and Jerry Richardson, Johannesburg, 1997. Photographer Jillian Edelstein Image source

On 28 July 1998, the MUFC became embroiled in a conflict with pupils from Daliwonga High School and as a consequence, Winnie and Nelson’s beloved house in Orlando West was set on fire and burnt to the ground. Winnie relocated to a bigger property - some would say a mansion – in Diepkloof and the MUFC moved with her.[xxvii] Shortly after the move, grim stories emerged about kidnappings, assaults and torture at the hands of the MUFC. One of the stories of kidnapping involved a youth whose name was to become synonymous with Winnie’s in years to come: Stompie Seipei.

Stompie

A thick veil of murkiness continues to engulf the truth around what happened to Stompei Seipei in 1988, the fourteen year old activist who fell foul of the MUFC. At the TRC hearing, the extent of clarity surrounding his death amounted to the following: that he went missing from his home, was beaten and ultimately murdered with a pair of gardening shears.

During the TRC it transpired that Stompie, along with three other missing boys, Gabriel Mekgwe, Thabiso Mono and Kenneth Kgase, was in the company of MUFC members prior to his disappearance and murder.[xxviii] Stompie’s body was discovered on the outskirts of Soweto on January 4.[xxix][xxx] Evidently, he had undergone a severe beating prior to his murder and Winnie’s old friend, Dr Abu-Baker Asvat had seen him for the injuries he sustained. Dr Asvat reported that Stompie was vomiting and could not eat and declared that he had suffered permanent brain-damage. On January 7, one of the other boys who had been with Stompie at Winnie’s home in Soweto, Kenneth Kgase, escaped and contacted Father Paul Verryn, a Christian priest whom Winnie alleged was guilty of abusing children in his care. Verryn took Kgase to a doctor and then to his friend Geoff Budlender, a lawyer, where Kgase described abductions and assaults perpetrated by MUFC.

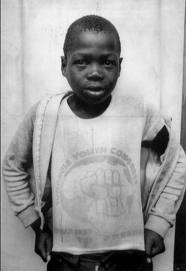

James "Stompie" Seipei, the 14 year old child who was brutally kidnapped and murdered by the Mandela United Football Club, with Winnie herself directly implicated. Photographer Gille de Vlieg

James "Stompie" Seipei, the 14 year old child who was brutally kidnapped and murdered by the Mandela United Football Club, with Winnie herself directly implicated. Photographer Gille de Vlieg

On 27 January, Dr Asvat himself was murdered by two young men posing as patients. Cyril Mbatha and Nicholas Dlamini were subequently convicted of his murder. By February 12, the murders of Stompie and Dr Asvat, along with rumours concerning MUFC, came to the attention of The Sunday Star. They broke the news nationally that Winnie may have been involved in Stompie’s beating and death. However, as a tide of popular opinion looked as though it were rapidly turning against Winnie, her name would quickly be knocked off the newspapers front pages, for the nation’s political forces were conspiring to free the world’s most famous prisoner.

Free Nelson

On February 2 1990, FW De Klerk used the opening of parliament to unban the ANC along with 31 other organisations. Political prisoners who had not committed violent crimes were to be released and executions of prisoners on death row were to cease. Also, in a major move, Nelson Mandela was to be released from jail. Just over a week later, on February 11, Nelson walked out of Victor Verster Prison hand in hand with Winnie to a reception of hundreds of thousands of supporters. The couple were finally reunited after almost 30 years of separation.

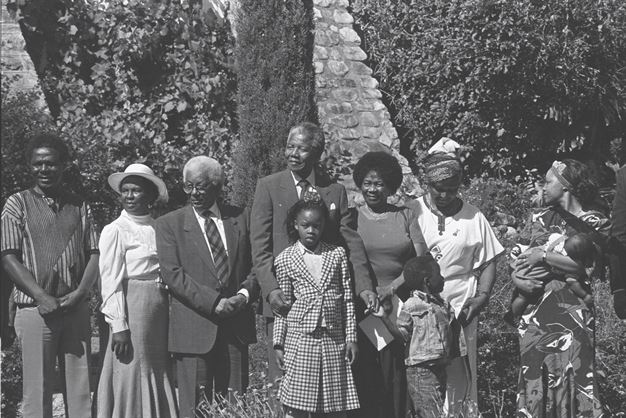

Walter Sisulu, Nelson, Winnie, Albertina Sisulu and the Mandela family Image source

Walter Sisulu, Nelson, Winnie, Albertina Sisulu and the Mandela family Image source

Each one a titan to the liberation struggle, Winnie and Nelson’s life after his release was a blur of travel, speeches and media obligations.[xxxi] Despite certain members of the ANC having grown increasingly frustrated with Winnie’s militancy and candour, Nelson elected to appoint her to the ANC’s head of Social Welfare in September. The decision was a controversial one but given her good relationship with the country’s youth (and de facto future voters), it was ultimately accepted by the dissenting voices within the party.

During this time, Winnie and her accessories in the MUFC were also standing trial for Stompie’s murder. Winnie was cleared of the murder itself but sentenced to five years in prison on four counts of kidnapping and one year as an accessory to assault. In the event she was granted leave to appeal and her bail was extended, with the courts eventually ordering her to serve a two year suspended sentence and pay a fine of R15 000. However, the allegations, the trial and the penchant for controversy were all taking their toll on the Mandelas, and the image of the happy couple was fading fast.

In her new role as head of Social Welfare, Winnie continued to court controversy when financial irregularities began to show up on her receipts and rumours emerged surrounding a possible affair she was having with her deputy, a young articled clerk by the name of Dali Mpofu.

Yet even in light of her involvement with the unsavoury behaviour of the MUFC, the fate of Winnie after Nelson’s release might be considered to be unfortunate. One of Winnie’s biographers has offered the following:

“In the worldwind of events following Mandela’s release from prison and the start of negotiations designed to ensure a peaceful transition rather than a bloodbath in South Africa…no one bothered to find out what Winnie needed and wanted, how her life had changed or what her aspirations might be… From the moment she was implicated in the serious crimes involving the football club, it was as though her entire past had been erased from the public mind.”[xxxii]

Irrespective of the actual reasons for Winnie’s waning standing amongst top members of the ANC and the media, the truth was that following the Nelson’s release any image of her as an uncomplicated, beneficent mother figure were surely gone. Similarly, whether it was time and distance, lifestyle or politics, Winnie and Nelson’s union was fast approaching its conclusion and on April 13 1992, Nelson called a media conference and announced that he was separating from his wife.

On September 6 1992, The Sunday Times got hold of a letter Winnie had written to Mpofu making mention of, amongst other things, ANC welfare department cheques that had been cashed for him.[xxxiii] It was virtually the death knell for any aspiration Winnie may still have had for a career in politics and on September 10 Winnie resigned all her positions in the ANC.

Winnie’s political career was all but over, and despite a brief stint as the head of the ANC Women’s League at the end of 1993 and again in 1997, her retreat from political life had begun. To add insult to injury, by the time Nelson was formally inaugurated as President of the new South Africa, Winnie’s position at the ceremony was not even amongst the distinguished guests.

In August 1995, Nelson instituted divorce proceedings against Winnie and in March 1996, the divorce was finalised.

TRC

By the time the TRC was established in February 1996, Winnie had enough accusations made against her to warrant an appearance at an in camera hearing of the Human Rights Violations Committee. Winnie appeared before the TRC in 1997, which judged her to have been implicated in a number of assaults and murders carried out by the MUFC. At the end of Winnie’s own testimony, the chairman of the committee, Archbishop Desmond Tutu implored her to admit that whatever her intentions might have been in Soweto in the late 1980s, that “things went wrong.” Winnie responded that indeed “things went horribly wrong” and she apologised to the families of Stompie Seipei and Dr Abu-Baker Asvat.[xxxiv]

Post Apartheid Activities

Following the end of Apartheid, Winnie continued to campaign for issues she strongly believed in. For instance, in June 2000, she travelled to Zimbabwe to express solidarity with the ‘war veterans’ taking over white farms, and in July 2000 she wore a T-Shirt emblazoned with the words ‘HIV positive’ and joined the chorus of voices demanding free anti-retrovirals for sufferers of HIV. This latter incident both highlighted her principles and gestured towards the ever fractious relationship she had with then President Thabo Mbeki.

In her personal affairs, the media reported numerous financial irregularities involving Winnie’s name, including a R1 million scandal also involving the African National Congress (ANC) Women’s League.[xxxv]

On June 16 2001, offering Winnie some respite from the media’s disclosure of her unusual financial activities, an incident was captured on television of an extraordinary encounter with Mbeki onstage at a Youth Day rally at Orlando Stadium. Winnie arrived an hour late to the event, and despite interrupting a speech by the chairman of the National Youth Commission, received a huge outpouring of support when the crowd saw her stepping out of her car. Mbeki was already onstage and visibly unamused by the interruption. On the way to her seat on the platform, Winnie stopped behind Mbeki’s chair and bent down to greet him with a kiss. Mbeki snapped and pushed Winnie away, knocking her baseball cap off her head in the process, only for Home Affairs minister Mangosuthu Buthelezi to retrieve it and place it gently back on Winnie’s head.[xxxvi]

Nadira Naipaul Interview

In 2010 an English newspaper, The Evening Standard, published an interview with Winnie by Nadira Naipul that claimed to accurately quote her talking disparagingly about her relationship to her husband, Desmond Tutu and the TRC.[xxxvii] Naipul insists that the controversial interview took place, but Winnie vehemently denies this.[xxxviii] The truth of the matter remains unknown.

Conclusion

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela remains an enigmatic figure in South African society and history. It has been speculated that like so many South Africans traumatised by the brutality of life under Apartheid, Winnie may have long suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and her actions ought to be understood in light of this. [xxxix] Despite her occasionally “morally ambiguous” behaviour, Winnie is someone whose commitment to justice and the downtrodden has seldom been in doubt, though her means of achieving her goals have drawn justifiable scrutiny.[xl]

Following the first decade of the 21 century, Winnie has been relatively quiet, though the public did turn its attention briefly her way when Nelson Mandela passed away on December 5 2013. Mandela’s death also coincided with the release of the movie 'Long Walk to Freedom' in which Winnie’s character was played by British actress, Naomi Harris.

with Julius Malema and Cyril Ramaphosa at her 80th birthday celebrations at the Mount Nelson Hotel on 13th September 2016 Image source

with Julius Malema and Cyril Ramaphosa at her 80th birthday celebrations at the Mount Nelson Hotel on 13th September 2016 Image source

On 15 September 2016, in a pre-birthday celebration, Winnie celebrated her 80 birthday at the Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town. The event was attended by family, friends and a cross-mixture of politicians including Julius Malema, Cyril Ramaphosa and Patricia de Lille.

Winnie passed away on 2 April 2018. Family spokesman Victor Dlamini said in a statement: "She died after a long illness, for which she had been in and out of hospital since the start of the year. She succumbed peacefully in the early hours of Monday afternoon surrounded by her family and loved ones."

Endnotes

[i] ‘Winnie: Soweto's most famous lady’ published on joburg.org.za. See http://joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=5036&Itemid=188 (last accessed 23 January 2017) ?

[ii] Bezdrob, Anne Marie du Preez (2003) Winnie Mandela: a Life. Cape Town: Zebra Press. ?

[iii] Ibid 23 ?

[iv] Ibid 29 ?

[v] Ibid 35 ?

[vi] Ibid 38 ?

[vii] Ibid 47 ?

[viii] Ibid 55 ?

[ix] South African Women Protest Pass Laws. See http://www.africanfeministforum.com/south-african-women-protest-pass-laws/ (last accessed 23 January 2017) ?

[x]Daley, Suzanne (1997). ‘Winnie Mandela's Ex-Bodyguard Tells of Killings She Ordered.’ The New York Times. ?

[xi] Ibid 137 ?

[xii]Bezdrob 90 ?

[xiii]Ibid 97 ?

[xiv]ibid 115 ?

[xv]ibid 127 ?

[xvi]Ibid 138 ?

[xvii] Winnie Mandela Facts.’ See http://biography.yourdictionary.com/winnie-mandela (last accessed 22 January 2017) ?

[xviii]Bezbrob 142 ?

[xix]Ibid 158 ?

[xx]Ibid 170 ?

[xxi]Ibid 186 ?

[xxii]Ibid 214 ?

[xxiii]Ibid 220 ?

[xxiv]Ibid 221 ?

[xxv]Ibid 223 ?

[xxvi]Daley ?

[xxvii]Bezdrob 223 ?

[xxviii] Parker, Faranaaz (2010) ‘Paul Verryn: what went wrong.’ The Mail and Guardian 29 January 2010. See http://mg.co.za/article/2010-01-29-paul-verryn-what-went-wrong (last accessed 30 January 2017) ?

[xxix]Bezdrob 223 ?

[xxx]Daley ?

[xxxi] Bezdrob 237 ?

[xxxii] Ibid 239 ?

[xxxiii] Ibid 240 ?

[xxxiv] Daley ?

[xxxv] Bezdrob 265 ?

[xxxvi] ‘Mbeki brushes off Winnie.’ News 24 Archives ?

[xxxvii] Naipul, Nadira (March 8 2010). ‘How Nelson Mandela betrayed us, says ex-wife Winnie.’ The Evening Standard. ?

[xxxviii] Naipul, Nadira (July 16 2010). ‘The Immortal Truth about Mandela: interview with Winnie by Nadira Naipul. http://mayihlomenews.co.za/ ?

[xxxix]Bezdrob 218 ?

[xl]Ndebele, Njabulo (2016) ‘Contemplating the intricacies of Winnie Mandela.’ The Mail and Guardian. ?

Bezdrob, Anne Marie du Preez (2003) Winnie Mandela: a Life. Cape Town: Zebra Press. | Daley, Suzanne (1997). ‘Winnie Mandela's Ex-Bodyguard Tells of Killings She Ordered.’ The New York Times. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/04/world/winnie-mandela-s-ex-bodyguard-tells-of-killings-she-ordered.html (last accessed 20 January 2017) | Naipul, Nadira (March 8th 2010). ‘How Nelson Mandela betrayed us, says ex-wife Winnie.’ The Evening Standard. Available at http://www.standard.co.uk/news/how-nelson-mandela-betrayed-us-says-ex-wife-winnie-6734116.html (last accessed 28 January 2017). | Naipul, Nadira (July 16th 2010). ‘The Immortal Truth about Mandela: interview with Winnie by Nadira Naipul.’ Available at http://mayihlomenews.co.za/ http://mayihlomenews.co.za/the-immortal-truth-about-mandela-interview-with-winnie-by-nadira-naipaul/#more-1931 (last accessed 24 January 2017). | Ndebele, Njabulo (2016) ‘Contemplating the intricacies of Winnie Mandela.’ The Mail and Guardian. Available at http://mg.co.za/article/2016-09-29-contemplating-winnie-mandela (last accessed 28 January 2017). | News 24 Archives ‘Mbeki brushes off Winnie.’ Available at

http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Mbeki-brushes-off-Winnie-20010616 (last accessed January 25 2017). | South African Women Protest Pass Laws. See http://www.africanfeministforum.com/south-african-women-protest-pass-laws/ (last accessed 23 January 2017) | Winnie: Soweto's most famous lady’ published on joburg.org.za. See http://joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=5036&Itemid=188 (last accessed 23 January 2017)