Introduction

Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu (née Nontsikelelo Thethiwe) was one of the prominent anti-apartheid South African leaders, widely referred to as the “Mother of the Nation”. Albertina Sisulu was one of five children born to Bonilizwe and Monikazi Thethiwe in the Tsomo district in the Transkei on 21 October 1918. She was a nurse, a political activist and council to her husband former Secretary-General and Deputy President of the African National Congress (ANC), Walter Sisulu.

Early Life

In September 1918 the Spanish Flu, a strain of the influenza virus that had killed 40 million people worldwide, reached South Africa and is estimated to have killed over 30 000 people in the Transkei. Monica Thethiwe (née, Mnyila), caught the virus and was seriously ill whilst pregnant with her first daughter and her second born, Nontsikelelo. “Umbathalala”, as the flu was called in isiXhosa, was lethal to pregnant women and small babies, however, baby Nontsikelelo was born perfectly healthy on 21 October 1918. She would later become the primary caregiver to her four siblings.

Education

Nontsikelelo and her family went to live with her maternal family in Xolobe, because her mother was constantly ill after surviving the Spanish flu and her father went to work in the mines. She attended a local primary school in Xolobe that was run by Presbyterian missionaries, and it was standard procedure that Black learners had to choose Christian names from a list presented to them by the missionaries. Nontsikelelo chose the name Albertina.

Albertina excelled at school in cultural and sporting activities. She showed leadership skills from an early age when she was chosen as head girl of her school in standard five. However, Albertina was forced to leave school on several occasions to take care of her younger siblings, because her mother was constantly ill, resulting in Albertina falling behind by two academic years. This two-year gap proved an obstacle later when she was disqualified, because of her age, from a competition that she had entered and won a four-year scholarship. Since the competition call had not stipulated an age limit, Albertina’s teachers wrote to the local isiXhosa newspaper, Imvo Zabantsundu, making a strong case for Albertina to be given the prize which she had come in first place for. The article caught the attention of the priests at the local Roman Catholic Mission who then communicated with Father Bernard Huss at Mariazell College, who arranged for a four-year high school scholarship for Albertina at Mariazell College. The Mnyila family was very happy and celebrated Albertina’s achievement with the entire village, Albertina recalls that the celebration saying, “you would have thought it was a wedding”.

In 1936 Albertina left for Mariazell College in Matatiele in the Eastern Cape where her anxieties were eased by the discovery that the college’s prefect was a girl from Xolobe. The school’s routine was rigid and strict; pupils were woken up at 4am to bath and clean their dormitories and they would then proceed to the chapel for morning prayers. Although Albertina’s scholarship covered her board and lodging, she had to pay it back during the school holidays by ploughing the fields and working in the laundry room. Albertina only went home during the December holidays, but she found this a small price to pay for the opportunity to attend high school.

After successfully completing high school in 1939, Albertina decided that she would pursue a profession that would enable her to support her family in Xolobe. Whilst at Mariazell, Albertina had converted to Catholicism and because she had resolved never to marry she decided that she would become a nun as she admired the dedication of the nuns who taught at the college. However, Father Huss advised Albertina against this as nuns did not earn a salary and did not leave the mission post, so she would not have been able to support her family in the way she wanted to. Instead, he advised her to consider nursing, as trainee nurses were paid to study. The practicality of this suggestion was appealing, and Albertina applied to various nursing schools. She was accepted as a trainee nurse at a Johannesburg “Non-European” hospital called Johannesburg General and left Xolobe for Johannesburg in January 1940.

Career

South Africa in the 1940s was defined by significant economic and political changes, determined by the Second World War and by the introduction of formal apartheid in 1948. The labour market experienced phenomenal growth because of an increased demand in the manufacturing sector, where goods that were previously produced in Europe, were produced locally because of the war. Many Black South Africans were drawn into the manufacturing sector on the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and there was a great increase in the number of women who joined the labour force for the first time. A small portion of this new group of female migrants moved to the city with the intention of pursuing higher education in the fields of nursing, teaching or social work and it is amongst this group that Albertina found herself. For Albertina, Johannesburg represented a totally different life to the one she experienced in Xolobe. She had heard stories of the “tsotsis”, of the wild parties and nightlife and of the dangers of living in the city. Despite all this, Johannesburg represented a promise of a better life where Albertina could earn a decent wage to support her family back home in the Transkei.

While she loved the work of nursing, her workplace became the place where she experienced racism for the first time. There seemed to be an unofficial policy of racial segregation amongst the staff of Johannesburg General as White nurses, regardless of age or experience, were treated and behaved as superior to their Black colleagues. Albertina was shocked at the way junior White nurses would order Black sisters around. Coming from a rural village with very few White people, Albertina had never been exposed to racism and racial prejudice before. Six months into her training she witnessed blatant racism and discrimination against Black patients who were admitted to the hospital after a horrific accident at Park Station, Johannesburg’s central bus and train terminus. The accident’s victims were flooding into the hospital and all staff members were on call, including those who were on leave. The Non-European section of the hospital was swamped with patients and the senior Black medical staff appealed to the hospital authorities to allow Black patients to be treated in the European wards, but the hospital authorities would not allow it. Due to the lack of available bed space, seriously injured patients were forced to sleep on the floor. This incident had a profound effect on Albertina as she could not believe that medical practitioners would violate their duty and deny patients care, solely based on their skin colour. This sparked outrage and evoked the strong sense of responsibility to act.

In addition to the disappointingly low wages she earned, the hospital administration imposed strict and unreasonable restrictions on Albertina and other Black nurses. For example, in 1941 she was denied leave to attend her mother’s funeral in Xolobe.

Political activity

Albertina’s introduction to politics was directly linked to her relationship with Walter Sisulu. Prior to her relationship with Walter, Albertina had never participated in political activities. Albertina met Walter in 1941 at the nurses’ residence through one of her cousins. It turned out that Walter was the brother and cousin of two of Albertina’s closest friends at the hospital, Rosabella (Barbie) Sisulu and Evelyn Mase. Although she was at first hesitant to start a relationship with Walter, because Barbie and Evelyn related to her as an older sister, she eventually decided to take Walter up on his invite to the “bioscope” (movie cinema) and their relationship developed from there. Albertina regularly accompanied Walter to his political meetings, but only in a supportive role and not with the intention of becoming actively involved. She was the only woman present at the inaugural conference of the African National Congress’ Youth League in 1944, hesitant to join the movement since it was apparent that it was a young men’s league. Albertina qualified as a nurse and married Walter Sisulu in that same year. Nelson Mandela and then wife Evelyn were best man and bridesmaid at the Sisulu wedding at the Bantu Men’s Social Club in Johannesburg on 15 July 1944.

The Sisulu’s wedding in 1944

The Sisulu’s wedding in 1944

Albertina and Walter Sisulu lived at No. 7372 in Orlando, Soweto. The house belonged to Walter’s family, and it was here that their first son – Max Vuyisile – was born in 1945. The Sisulu house was always busy with visitors constantly moving in and out, many of whom were prominent political leaders. Miriam Matsha, Albertina’s sister-in-law, has commented that “the best political education I had was living at No. 7372”. Walter decided to quit his job and join the ANC full time around 1947 and Albertina accepted the responsibility of supporting the family as the sole bread winner; a brave decision given that the wages of Black nurses was low. In 1949 Albertina supported Walter’s election as the first full-time Secretary-General of the ANC. The ANC only began accepting women as members in 1943 and in 1948 the ANC Women’s League was formed. Albertina Sisulu joined as a member; this was the beginning of Albertina’s life as an activist in her own right.

After joining the ANC Women’s League, Albertina began to assume leadership roles in the ANC and in the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) in the 1950s. She was one of the organizers of the historic anti-pass women’s march in 1956 and opposed inferior `Bantu’ education. Her home in Orlando West in Soweto was used as a classroom for alternative education until a law was passed against it. Both Albertina and her husband were jailed several times for their political activities and she was constantly harassed by apartheid security.

In the 1960s the ANC moved toward the armed struggle and Umkhonto we Sizwe (the ANC’s armed wing) was formed in 1961 by Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela. Walter was responsible for framing the organizational units of the National High Command, Regional Commands, Local Commands and cells. In 1963 while he was awaiting the outcome of an appeal against a 6-year sentence, Walter decided to forfeit bail, and go underground. Apartheid security visited his house and found that he had fled. Soon afterwards they arrested Albertina and her young son Zwelakhe, making her the first woman to ever be arrested under the General Laws Amendment Act. The Act gave the police the power to hold suspects in detention for 90 days without charging them, and in Albertina’s case she was placed in solitary confinement incommunicado for almost two months while the Security Branch looked for her husband. During this period, she was psychologically manipulated into believing her children were ill and that Walter had died when in fact he had been arrested and would go on to be one of the Rivonia trialists who were sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island in 1963.

The Sisulu’s children were effectively orphaned after the arrest of their parents Image source

The Sisulu’s children were effectively orphaned after the arrest of their parents Image source

As Walter and his co-accused left the courtroom, Albertina Sisulu, some ANC Women’s League members and other supporters rushed out to form a guard of honour to meet the men. The court officials turned them away, but they sang ‘Nkosi Sikele i’Afrika’ in Church Square in Pretoria in solidarity and mourning. Albertina was detained and put in solitary confinement again in 1981 and 1985 for her activism. She was also placed under multiple bans, and under house arrest, but still managed to keep links between jailed members of the ANC and those in exile. In 1983 Albertina was elected co-president of the United Democratic Front (UDF), and in June 1989, the government finally granted her a passport. The following month she led a delegation of UDF leaders to Europe and the United States. She met the British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher and the American President, George Bush Snr. In October 1989, the last restrictions on the Sisulu family were lifted and Walter was released from Robben Island.

Albertine at a UDF conference in Johannesburg in 1983 Image source

Albertine at a UDF conference in Johannesburg in 1983 Image source

Walter Albertina celebrate his release from prison in Soweto in 1989. Image source

Walter Albertina celebrate his release from prison in Soweto in 1989. Image source

The Defiance Campaign of 1950-1952 was a turning point in the national struggle for liberation for many reasons; the mass support it generated sent a strong message to the government about the organizational strength of African leaders, the United Nations recognized that South Africa’s racial policies was an international issue and a UN Commission was established to investigate the situation, the ANC’s membership increased exponentially, and a new era of non-racial resistance to apartheid was set in motion. This also propped up the ANC Women’s League and led to the formation of FEDSAW on 17 April 1954 in Johannesburg. It aimed to establish a broad-based women’s organization that would not only fight for national liberation, but specifically address issues of gender inequality that were driven by the state against non-White women. The Women’s Charter was adopted at the inaugural conference which was attended by 150 women from all over South Africa. During the early stages of the federation, Albertina was not in a central position of leadership, but she was actively committed to promoting the ideals of FEDSAW.

Albertina earned her midwife qualification in 1954 and was subsequently employed by the city’s Health Department as a midwife. The job was challenging but Albertina still made sure to visit her patients in their homes in townships. She carried a suitcase full of her apparatus (bottles, lotions, bowls and receivers) on her head because she walked to her patients. She would take FEDSAW pamphlets with her to encourage the women to join the federation. In 1955 FEDSAW was actively involved in the ANC’s boycott of Bantu Education and Albertina was heavily involved in the preparations of the boycott. The ANC Women’s League and FEDSAW aided the boycott greatly by opening alternative schools for children that were supported by the ANC as well as teachers who had resigned from their jobs in protest of Bantu Education. Albertina’s home became an alternative school as her children had been withdrawn from their government schools. The apartheid state responded by making it illegal to run alternative schools and it announced that it would shut down all boycotting schools permanently. This resistance from the government, and the fact that alternative schools were not viable long term, had parents returning their children back to the government schools. Several Christian schools decided to continue as private schools rather than being placed under the control of the Bantu Education Department and Albertina and Walter decided to send their children to a private Seventh Day Adventist school despite the considerable financial burden this would place on them.

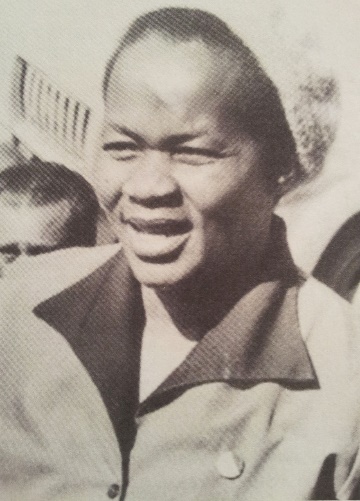

Albertina a staunch activist in her own right Image source

Albertina a staunch activist in her own right Image source

The 1956 women’s anti-pass protest was a historic moment for South Africa and women’s movements. About 20 000 women gathered from all over the country to march to Union Buildings demanding to see Prime Minister Stijdom to hand over their memorandum. After the ANC Women’s League’s first national conference at the end of 1955, the League and FEDSAW set up a joint working committee to coordinate the women’s anti-pass campaign. Networks and meetings were organized with regular weekend meetings being held in townships, the success of which convinced FEDSAW and ANC women leaders that a mass protest would be an effective means of protest, despite some reservations from male comrades in the ANC. Transporting women to Pretoria was perhaps the biggest logistical challenge to the march, because of the financial cost as well as the reactionary measures taken by the police. Albertina was one of the leaders who had to ensure that women bypassed the reported police stops that were barring groups of ten or more women from traveling to Pretoria. It was decided that the trains would be used as these would be harder to stop than busses, and Albertina was at the Phefeni train station at 2am on the 9th August 1956 buying and distributing tickets to women attending the march. The march itself was phenomenal. Bundles of petitions with more than 100 000 signatures were placed outside the Prime Minister’s door whilst 20 000 women stood in silence for 30 minutes with their hands raised in the Congress Salute. After singing freedom songs, especially the famous “Wathint` abafazi, Strijdom! Wathint` imbokodo uzo kufa!” (Now you have touched the women, Strijdom! You have struck a rock, You will be crushed!), the women left the Union Buildings together in unity and solidarity.

Albertina was influential in the 1956 women’s anti-pass protests Image source

Albertina was influential in the 1956 women’s anti-pass protests Image source

During 1958 the South African Nursing Council demanded that all nurses and student nurses supply their identity numbers to the council. Immediately nurses realised that this demand was linked to the government’s attempts to extend pass laws and pass books to women and a demonstration was organized at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. A delegation of nurses leading the demonstration warned the Nursing Council that forcing nurses to carry passes would have a devastating effect on hospital and clinic administration and after considering this the Council dropped their demands. In the same year a demonstration of over 1000 women (led by Maggie Resha) converged on Freedom Square in Sophiatown to protest against ongoing removals in Sophiatown. Women in Alexandra were also protesting against passes. Over 2000 women were jailed for participating in these demonstrations, including Albertina as she was part of a demonstration organized by the ANC Women’s League in Orlando. The women were in jail for three weeks awaiting trial. They had Nelson Mandela as their legal representative and eventually they were all acquitted at the end of the trial.

To visit Walter, Albertina was forced to apply for a passbook as no-one could visit Robben Island without one. This process was very humiliating and degrading for her, she had never owned a passbook and had engaged in active resistance against the use thereof. The officials who administrated Albertina’s passbook mocked her by asking her where she had been when others had applied for their reference books years ago. They aggravated circumstances further by deliberately delaying the administrative process.

On top of all of this Albertina was served with a five-year banning order (valid until the 31st July 1969) which limited her movement and activities according to ‘Group B’ restrictions. For five years Albertina was not allowed to leave the magisterial district of Johannesburg. Although the ‘Group B’ restrictions were less severe than those of ‘Group C’ (24 house arrest), Albertina’s banning order prevented her from visiting all townships, hostels, villages or compounds where Black people lived. She was also prohibited to visit any factory, newspaper or magazine office, university, school, college, or educational institution, and any Coloured or Asian area, except Orlando where she lived. She was further barred from communicating with any banned or listed person (list of individuals who the state wanted to persecute or were suspicious about) except her husband. In addition to this she was not allowed to be involved with the compiling, printing or distribution of any publication, or to give any educational instruction to any person other than her own children. Albertina was banned from attending social, political or student gatherings – a “gathering” being defined as more than three people present and/or any number of persons of different races being together. Albertina also had to report to the Commanding Officer of the Orlando Police Station every Wednesday.

Empty chair at a protest meeting for banned anti-apartheid activist Albertina Sisulu. Photographer: Gideon Mendel Image source

Empty chair at a protest meeting for banned anti-apartheid activist Albertina Sisulu. Photographer: Gideon Mendel Image source

When Albertina’s permit to visit Robben Island arrived she had to apply to the Chief Magistrate for special permission to leave Johannesburg. In turn the Magistrate had to refer the matter to the security police. Eventually Albertina was able to visit Walter in September 1964, but the same restrictions applied to her in Cape Town and although she informed the police of all her arrival and departure times, her movements were closely watched over by local police.

Albertina’s first Christmas without her husband was difficult. Over and above the pain of not being with Walter, she was faced with dire financial problems. Her children returned home from school in Swaziland for the December holidays and she was concerned that she might not be able to feed them. Holiday celebrations were a bleak affair as many of Albertina’s friends and comrades were either in prison or in exile. Albertina remembers the following about the 1964 festive season:

“There was hardly anything to eat and I had to close the doors and windows to keep out the aroma of delicious food coming from the houses of our neighbors. We were so lonely. The people who we would normally spend the day with were not there. It was the worst Christmas we had ever had.”

Albertina’s financial woes continued throughout the 1960s as she struggled to afford her children’s schooling in Swaziland, but she said that she would rather struggle than subject her children to Bantu education. When she was not at work, Albertina sewed ‘lishweshwe’ dresses, knitted jerseys and baby clothes to sell for extra money and she also bought eggs at wholesale prices, selling them at a small profit. From grocers who allowed her to buy on credit, to friends who would lend her money to buy school supplies for her children, to neighbors who would donate coal for cooking free of charge every month - in these difficult times her neighbors and friends were kind and supportive. Anglican priests in South Africa who were friends with Albertina and Walter also helped her out by either paying for the children’s school fees or helping them to secure bursaries from overseas donors.

Even though Albertina was under constant surveillance by the security police she still managed to exchange political information with Walter and a network of other activists. In a letter dated 25 November 1965, Albertina cryptically wrote the following:

“Our gardens are not too good at all this year. The drought has been too much. The worms are so powerful that as soon as you put in plants they are destroyed instantly.”

Albertina was referring to the fact that informers (worms) were defeating the work of the ANC underground (gardens) which was made worse by the repressive political climate (drought). As a FEDSAW leader and ANC stalwart who was not imprisoned Albertina had to do her best to dodge the security police so that she could communicate with ANC comrades and other activists. One such person was John Nkadimeng who was closely associated with Walter in the ANC before he joined the Communist Party and was also a target of apartheid security. John and Albertina managed to contact each other during 1966 and together they set up an underground cell. They were joined by activist John Mavuso and the three of them maintained contact with the ANC leadership in Botswana. The cell’s main activity was to help ANC members to leave the country for education or military training and they managed with the help of others to set up a working committee to facilitate this.

Nkadimeng and Albertina went about setting up links with activists in other provinces which proved to be very difficult because of their banning orders and the ban on formal meetings. Nkadimeng would visit Albertina at her clinic pretending to be a relative. They would discuss political matters by pretending to be chatting about family matters. Other underground activists would also go to the clinic and pretend to be patients and they would exchange information as Albertina attended to them. Between 5pm when she finished work and 7pm when she had to report to the police station, Albertina managed to sneak off to meetings. One of her sons, Lungi, assisted her as courier and driver to other activists. He often picked up messages and parcels for his mother.

Albertina also managed to keep in contact with her FEDSAW comrades through very unconventional but ingenious methods; one of which involved conversations through a toilet wall. The toilet in Albertina’s house, like most in her area, shared a wall with her neighbour, Metty Hluphekile Kubheka. Kubheka moved in next door in the mid-1960s. FEDSAW members would pretend to visit Kubheka but would converse with Albertina through the thin adjoining toilet wall while Kubheka kept a look out in the front garden for the security police.

Albertina always had to be extremely careful as police informants were all over neighbourhood, the clinic and even posed as members in the movement. Towards the end of 1967 Albertina grew suspicious that John Mavuso was a police informant. He was their main contact with the ANC leadership in Lusaka and after he opened a new factory and Albertina was unsure where he had managed to get the money. After an investigation carried out by John Nkadimeng it turned out that Albertina’s suspicions were correct. They decided not to confront Mavuso about the matter, but they stopped all business with him.

In addition to the constant surveillance, the security forces tried to break the nerve of political leaders using psychological tactics. In July 1966 Albertina received a letter from the Liquidator informing her that he had evidence that she was a member of the Communist Party and that FEDSAW was under “communistic domination and control” because its leaders; Albertina, Eufemia Hlapane and Gertrude Shope, were confirmed communists. In a back and forth exchange of letters between Albertina, the Ministry of Justice and the Liquidator the allegations were dropped but the psychological strain of the ordeal affected Albertina. The security forces also stirred up gossip in the townships making people suspicious of their comrades, asking questions like “why are their children studying in boarding schools in Swaziland when ours are in township schools?”

In July 1969, exactly five years after her first banning order the state informed Albertina that her banning order had been renewed for another five years and that she was being placed under partial house arrest. The security police justified their decision by saying that Albertina had continued her involvement in FEDSAW and had continued to engage in illegal political activities. The security police report used in extending Albertina’s banning order contained many fabrications, some of which were completely fantastical. The police were correct that Albertina was still a member of FEDSAW. The usual allegations that Albertina was a member of the Communist Party were included in the report, along with allegations that she was planning to buy a property for returning freedom fighters (‘terrorists’). By far the most bizarre allegations were that she had communicated with her husband by putting a “secret message” into the frames of the new spectacles she had bought him and that a white man called Platz-Mills from London had given Albertina a secret writing apparatus that looked like a mirror so that she could communicate with leaders abroad. The security police were also very interested in the rift between Albertina and Winnie Mandela and alleged that Albertina was “competing with Winnie for the leadership of FEDSAW” – a ridiculous allegation as Winnie was not a member of FEDSAW or of any affiliated organization. These allegations were merely used to convince the Ministry of Justice to impose further restrictions on Albertina.

Although the 1960s were tough, Albertina felt that significant work had been done in rebuilding the underground and community structures of FEDSAW and the ANC. In September 1968 she wrote to Walter, using the same metaphors as before, saying that:

“Though we have not got enough rain yet this year, our gardens are not as poor as all these other years. I think by next year we will have enough vegetables. So rest in peace in the Island. We are not going to starve long.”

The renewed banning order made it almost impossible for Albertina to network with FEDSAW and the ANC members as she was under partial house arrest. During this time, she kept Walter up to date with family matters, writing to him constantly about their children’s school achievements. The Sisulu house was always busy as extended family, friends and neighbors often visited and political activists came by to exchange information and of course there were the obtrusive police raids. Albertina was a busy house wife; this amazed her children who appreciated the political stress she was under. In 1972 some of Albertina’s children clubbed together to buy her a washing machine for her 54th birthday. Sheila Sisulu (daughter-in-law, married to Lungi Sisulu) commented on this occasion: “I felt so guilty about Mama doing laundry all the time and I was not about to spend my days helping her with the washing. At first she distrusted the machine and felt it did not wash the clothes properly, but after the first few washes she was so impressed that she named the machine ‘MaSisulu’. When the washing machine was churning out load after load we would jokingly say ‘MaSisulu is busy today!’”

Throughout her life Albertina had always been mothering. From when she had to take care of her younger siblings to her experience of motherhood with her own children and her late sister’s children, then later taking care of her grandchildren whose parents were away in exile. In African cultures, extended family (i.e. nieces and nephews) are part of the immediate family and Albertina frequently looked after her sister Flora’s children. Albertina had to make more room for her family and built extra ‘backrooms’ in the backyard of her house to accommodate everyone. Albertina always kept Walter up to date with these changes so that he would recognize No. 7372 when he returned home.

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was very popular amongst students of the 1970s and Lindiwe Sisulu (Albertina’s 4th child and first daughter) was active in the Black People’s Convention (BPC) from 1971-1973. Albertina was concerned with Lindiwe’s involvement with BPC because she disapproved of the way that many of the youths had interpreted the Black Consciousness (BC) philosophy with regards to White people. The ANC had always maintained a policy of non-racialism and while Steve Biko’s views on Whites in South Africa were not extreme, some of the BCM’s youth were bent on eliminating White people from South Africa. Despite her concerns, Albertina was supportive of her daughter and did not patronise her during the political conversations they enjoyed. Lindiwe felt that Albertina and John Nkadimeng were too passive and lacked real activity in merely working to set up structures.

On 25 April 1974 Mozambique was liberated by FRELIMO. This victory boosted the morale of the South African freedom fighters. Albertina’s second five year banning order was due to end that year, but it was renewed again for another five years. The partial house arrest requirement was removed, but she was prohibited to leave her own township of Orlando and she had to continue to report to the Orlando Police Station weekly. She had to apply for special permits to attend work-related lectures outside of Orlando from the Chief Magistrate of Johannesburg.

Nkuli Sisulu, Albertina’s daughter and youngest child, attended Morris Isaacson High. This school was centrally involved in the organization of the student protests. Before the 1976 riots Albertina could sense that Nkuli was hiding something from her and so could her siblings who saw the excitement that she was repressing. Nkuli and her cousin Jongi left home as normal with their school books on 16 June 1976 not speaking of the protest plans to anyone. Albertina was at work when she heard about the student protests but was not really worried about it because she did not imagine that they would be in any real danger. However, during the day Albertina became increasingly worried as reports about children being shot at and killed came in. On her way home that evening Albertina saw that the township had erupted into chaos, students were throwing stones at the police and cars and buildings had been set alight. Albertina had no idea where Nkuli and Jongi were, but they returned home later that day. The student riots continued through June and July. Albertina, like most parents, could not stop her children from taking part as the Sisulu children did not want to sit around at home while their friends and peers were out fighting on the streets. This period was very nerve wrecking for Albertina who never knew when her children would be home. Nkuli often came home badly bruised or burnt by teargas.

On top of this stress Albertina was very anxious about her daughter Lindiwe who had been taken into custody on 14 June. Initially Albertina did not know where Lindiwe had been taken and she feared the police’s increased brutality towards detainees. Fortunately, Albertina found Lindiwe the following day at John Vorster Square, the notorious detention centre where Steve Biko died. Lindiwe remained in detention for almost a year and suffered terrible physical and mental torture at the hands of the police. Many young people were either forced to leave the country or left voluntarily after the events of 1976. Lindiwe left for Mozambique in June of 1977 because she feared being detained again. Albertina facilitated the departure of many young people into exile post-1976 and there were many opportunities to mobilise not only the youth but also women. Albertina noted that women who had previously shunned her and her political activity because they were afraid to land up in jail had a change of heart. Primarily because of the involvement of their children in the student protests and the police brutality against them, but also because they wanted to become active members of FEDSAW.

In July 1979 Walter and Albertina celebrated 35 years of marriage; a marriage like no other with many children in exile (they had not seen Max, their firstborn, in 16 years) and with 15 years of not living in the same house. Two weeks after their wedding anniversary the security police arrived to serve Albertina with another banning order, this time it was a two-year ban. The report from the security police recognized that Albertina was a very good public speaker who could mobilize many people so the ban on attending “gatherings” remained.

Albertina addressing a ‘Free Mandela’ campaign rally in 1985 Image source

Albertina addressing a ‘Free Mandela’ campaign rally in 1985 Image source

Albertina and Helen Joseph were both under banning orders that prevented them from attending the funeral of long-time friend and fellow freedom fighter Lilian Ngoyi in 1980. The pair applied for permits to attend. Helen was granted leave to attend but Albertina’s application was denied. Despite these personal struggles, the initial climate of the 1980s was in favour of the liberation struggle as Zimbabwe gained its independence on 18 April 1980. This completely disarmed the apartheid regime’s plans to establish links with other African states in the region to support its policies of racial segregation and to prevent a “communist onslaught”. Sabotage acts against the state, most notably the bombing of police stations, increased greatly as the ANC relied on its armed wing – Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) – to retaliate against police brutality and the murders of political activists.

Albertina, Helen Joseph and Amina Cachalia Image source

Albertina, Helen Joseph and Amina Cachalia Image source

Fortunately, in July 1981, much to her surprise, Albertina’s banning order was not renewed. She had been banned for 18 years, the longest any person in South Africa had been banned. Her new ‘freedom’ meant that she could actively and openly set to work on rebuilding women’s organizations within FEDSAW, she was also inundated with requests to speak at meetings and rallies. However, despite the fundamental freedom of speech, she could not be quoted in newspapers as she had once been a banned person. On the 15th June 1982 Albertina was served with her fifth banning order, a two-year set of restrictions that barred her from attending any meetings (and funerals) where she was able to “expound her ideological views”.

Albertina worked closely with veteran activists like Greta Ncapayi, June Mlangeni and Sister Bernard Ncube. Much work was done to recruit young female activists who could organize the women in the ANC underground. A Soweto teacher O’Hara Diseko was one of these new recruits who Albertina sent to Botswana to discuss plans with the ANC Women’s Branch there. Albertina and O’Hara also formed a local cell called Thusang Basadi (‘help women’) with other women in the area to support detainees and the families of political prisoners. Thusang Basadi would help with the educating of political prisoners and with the organization of funerals, tracing missing members of ANC’s families. The cell staged protest marches outside of municipal offices, demanding that the dummy municipal structures and non-elected councils be dismantled.

Albertina had been banned from attending the conference in January where Reverend Allan Boesak proposed plans for increasing momentum in the resistance against apartheid, but she was in strong support of the plans. The timing for such an initiative could not have been more perfect as Albertina’s banning order was cut short due to the introduction of the new Internal Security Act of 1982. Her banning order ended approximately a year before it was due to. Albertina was eager to be involved with the preparations for the launch of the UDF as mass mobilisation on a national scale – across organizations and race – was desperately needed to change the political situation in South Africa. However, she was arrested on 5 August 1983 (probably because the state saw her involvement with the UDF as a threat) after the funeral of ANC Women’s League veteran Rose Mbele in January. She was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act for allegedly furthering the aims of the ANC – still banned at this time. The security forces’ ‘evidence’ was that Rose Mbele’s coffin was draped with an ANC flag and Albertina was asked to deliver a tribute to Rose’s life; facts which were distorted to incriminate Albertina for delivering a speech on behalf of the ANC. During this time the UDF section in the Transvaal held its Regional Executive Committee Elections and Albertina was elected president in absentia. In an article written about her election by the vice-president of the UDF for the Transvaal region, Dr. RAM Saloojee, Albertina was dubbed the ‘mother of the nation’.

Albertina’s trial date was set for the 17th October and she was denied bail. She remained in custody with Thami Mali (a teacher from Soweto accused of the same offences) in Diepkloof Prison. The international Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) publicised Albertina’s detention abroad with strong condemnation of the apartheid government. This caught the attention of the British Foreign Secretary who issued a statement of concern detailing the ‘strong feelings of repugnance’ that Britons felt towards the South African government. The fact that Albertina and Thami Mali were arrested a full eight months after Rose Mbele’s funeral implies that the state was not really interested in their actions at the funeral but rather in crushing the UDF in its early stages.

Being in jail did not prevent Albertina from participating in the struggle as 250 000 copies of the UDF News boasted a full-length image of her on the front page. The UDF News was distributed throughout the townships in the Transvaal during the UDF’s recruitment drive for its national launch. The launch of the UDF signalled a new chapter in the struggle for liberation as 12 000 to 15 000 people gathered in Mitchell’s Plain to show their support for South Africa’s largest democratic organization. More than 400 organizations throughout the country were affiliated to the UDF including trade unions, women’s groups, sports groups and faith-based and civic organizations. Albertina was elected as one of the three presidents of the UDF along with Oscar Mpetha and Archie Gumede.

George Bizos defended Albertina and Thami in court saying that the ANC’s presence at the funeral was necessary because of Rose Mbele’s history with the organization but the funeral was not a political rally for the ANC. On 24 February 1984 Albertina was sentenced to four years in prison, two of which were suspended for five years. Upon hearing the news of MaSisulu’s sentence, Priscilla Jana, lodged a successful appeal for bail and eventually after rigorous efforts, collected the required R1000 bail fee. Priscilla managed to get Albertina out of jail at midnight that night.

In 1984 Albertina retired from the Council of Nurses to work with Dr Abu Asvat who worked from a mobile clinic (housed in a caravan) in Rockville Soweto. Dr Asvat was politically aligned with AZAPO (Azanian People’s Organization) and was deeply committed to helping the poor. Despite their different political persuasions Albertina and Dr Asvat worked in perfect harmony as both were passionate about serving the poor and overthrowing the apartheid state. Dr Asvat also understood the nature of Albertina’s UDF work and the risk that she could be jailed or banned at any time. He allowed her extensive leave to visit Walter in Cape Town.

By the end of 1984 the UDF had over 600 affiliates and its boycott campaign was the most vigorous and sustained political campaign run by Black South Africans. The ANC had also declared 1984 the ‘Year of the Woman’ and Albertina was part of a group of activists tasked with the challenge of reviving FEDSAW. It was decided, for fear of being banned, that FEDSAW should exist as a network of connected but independent provincial organizations and Albertina set Sister Bernard Ncube and Jessie Duarte the task of drawing veteran activists into the process of building up FEDSAW. As leader in charge, Albertina also maintained that it was vital that FEDSAW communicated and sought the council of women in exile. In her public statements during this period Albertina continually emphasised the role of women in the struggle and combined this with the campaign against the tri-cameral parliament.

Riots, boycotts and indiscriminate police shooting rocked the townships in 1984, but the state could not squash the will of the people and the riots continued throughout the year. The state blamed the UDF for the violence and considered banning the organization but concerns over international pressure and what could happen if the UDF went underground prevented this. Instead the state targeted the UDF leaders and in October and December 1984 nine UDF leaders were arrested. Shortly after this on the 19 February 1985 Albertina was arrested along with other UDF leaders and trade unionists, all of whom were transported down to Durban to join their UDF colleagues who had been detained the previous year. In total sixteen leaders were arrested and charged with treason and a trial date was set for 21 October, on Albertina’s 67th birthday.

All sixteen accused were denied bail with Albertina being the only woman accused. She was put in solitary confinement. Priscilla Jana remembers one occasion where she went to visit Albertina and found the men relaxing enjoying each other’s company over a game of chess while Albertina was alone in her cell scrubbing the floor. In April the French ambassador requested to see Albertina in jail but his request was denied after an embarrassingly diplomatic exchange of letters between the security police, the Ministry of Justice and the French embassy.

Throughout the country the UDF organized mass protests regarding the detainment of their leaders, and Dr Allan Boesak along with other UDF leaders challenged the government to arrest them too as they were ‘guilty’ of participating in the same activities as the accused sixteen. Finally, on 3 May 1985 the Natal Supreme court granted the accused bail of R170 000. But the bail conditions meant that Albertina and her co-accused could not participate in any organizations mentioned in the indictment. This put a halt on Albertina’s FEDSAW, UDF and ANCWL work.

The Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial began with pre-trail proceedings some time before the trial date of 21st October. The state had put together a 587-page indictment that alleged that the UDF was a political front for the ANC and that it was leading a ‘revolutionary alliance’ to overthrow the state. The specific charges were high treason, violations of the Terrorism Act and furthering the aims of the ANC. Once the trial began properly it was clear that the state had insufficient and unconvincing evidence against the accused sixteen. The key state witness (a lecturer at the Rand Afrikaans University) eventually conceded that he had made ‘fundamental mistakes’ that could have misled the court and that he, contrary to what the Attorney-General had argued, had no expertise to assess revolutionary literature. On 9 December the state withdrew its charges against twelve of the sixteen; the remaining four were South African Transport and Allied Workers Union (SAAWU) members who remained on trial. The twelve were met by a crowd who had gathered outside the courtroom to congratulate them. After her release, Albertina made her first public appearance at a meeting on International Human Rights Day in central Johannesburg where she delivered a speech saying that it was ‘the beginning of the end of the apartheid system’.

Violence in the townships continued with two State of Emergencies being called during 1985 and then again in 1986 which was extended until 1988. Police brutality was unprecedented and in Alexandra seventeen young people were killed in what the press called the ‘Six-day War’. A funeral was held for the victims and 60 000 people mourned their passing at Alexandra Stadium where Albertina delivered a speech that condemned the government as ‘frightened cockroaches’. She appealed to mothers of White soldiers for the government to stop killing Black children. 1986 was also the year that the UDF focused on the role of women as a key part of its programme of action, as a large majority of its members were women. In May the UDF National Working Committee Conference resolved that new women’s organizations be set up where none had existed, and that existing women’s groups be strengthened to lay a strong foundation for its national structure.

During 1986 tensions between AZAPO and the UDF came to a bloody head and hundreds of supporters on both sides were killed and the houses of leaders were bombed. The apartheid state was partly to blame for this as it had circulated fake UDF pamphlets in Soweto that incited anti-AZAPO sentiments. Considering this, it made Albertina and Dr Asvat’s working relationship and friendship particularly remarkable. Albertina always spoke highly of her employer, Dr Asvat who had continued to pay Albertina her salary whilst she was on trial and detained. During the time that they worked together they provided much needed help to people in some of the poorest communities. In McDonald’s Farm where people were living in abandoned cars they set up a surgery and installed 20 toilets that were shared by 150 people. Space for a crèche was made in the surgery and a feeding scheme was introduced that fed approximately 80 children. In January 1987 the leadership of the UDF and AZAPO committed to pursing a peace process and agreed to halt further attacks.

Towards 1994 and Beyond

Walter Sisulu was released in 1989; Albertina finally had her husband back. In the same year she was part of the UDF delegation that met United States president, George Bush, to establish relations between the two countries. Moreover, when the ANC was unbanned in 1990, Albertina worked on a committee that re-established the ANC Women’s League. At the time she was the organization’s deputy President. On 9 August, Albertina and other women from exile set up the first ANC Women League branch in Durban. In April 1991 The ANCWL held its conference and Albertina Sisulu was nominated to stand for President in the election but she withdrew in favour of Getrude Shope.

In 1991 Albertina was elected to serve on the ANC’s national executive committee and Walter was elected ANC Deputy-President to avoid a potentially divisive contest between Thabo Mbeki and Chris Hani. The pair attended the ANC conference in Lusaka where Albertina was elected the convener in South Africa. Her responsibility was to ensure that the structures of the ANC, especially the women’s section were being addressed. In August of the same year, Albertina and Walter visited Singapore, Australia and Mauritius. Later in the year they visited North America (7 major Canadian cities and New York, Washington, Atlanta and Boston).

In April 1994, the Sisulu’s observed the transition of the country in its first democratic elections. Albertina and Walter both became members of parliament. On 17 July Walter and Albertina celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

In 1996 Walter traveled overseas for the last time and Albertina went with him. They were on a fundraising trip to the USA, Ireland and the UK on behalf of Education Africa. In 1998 Albertina celebrated her 80th birthday, still working as a Member of Parliament as the president of the World Peace Council and as an ANC leader in her home constituency of Orlando West, Soweto. At the end of 1999 Albertina and Walter left parliament and retired from politics completely.

Conclusion

In 2002, ‘Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime’, a biography by Sisulu’s daughter-in-law Elinor, was launched by the Nigerian poet Ben Okri, who also wrote a tribute for Walter’s 90th birthday. The following year, while on their way to bed, Walter collapsed and died in Albertina’s arms. On 21 October 2008, Albertina and the nation celebrated her 90th birthday, which would be her second last birthday. MaSisulu died suddenly in her home on 2 June 2011, aged 92. President Jacob Zuma announced that Ma Sisulu would receive a state funeral, and that national flags would be flown half-mast from 4 June until the day of her burial.

Albertina’s state funeral in 2011 Image source

Albertina’s state funeral in 2011 Image source

- Gastrow, S. Who’s Who is South African Politics, Number 4, pp 282-283

- Sisulu, E (2003). Walter & Albertina Sisulu: In our lifetime. Claremont, South Africa: David Philip.

- Albertina Sisulu's story. women24.com

- The Albertina Sisulu Multipurpose Resource Centre/ASC, named after Albertina Sisulu, was founded by Albertina Sisulu. albertinasisulucentre.co.za

- Albertina Sisulu. Biography of distinguished woman. pages.interlog.com

- Leist, R (1991). I am Albertina Sisulu. Interview from Blue Portraits, September. anc.org.za

- (1988) Albertina Sisulu: Freedom Fighter. Sechaba, October.

Image archives:

- Jurgen Schadeberg. jurgenschadeberg.com

- South photographs. southphoto.com

- Bailey’s African History Archives. baha.co.za

- The Sisulu private family collection.

- Mayibuye Archives. Robben Island Museum (Heritage Department). email: mayib@uwc.ac.za