Archive category

Publication date

Published date

Download the file

Related Collections from the Archive

It’s early winter in Cape Town, cold and gray, when I take the 1044 train from Newlands station on a Saturday afternoon to meet the photographer Omar Badsha at his house in Woodstock. I sit in the half-empty carriage and page through one of his first photographic essays, Imijondolo: A photographic essay on forced removals in South Africa (1985).

Despite the grim subject matter of the work – the impending forced removal of a community of quarter of a million people living in the Inanda district, a shack settlement 30km northwest of Durban’s city centre – Badsha’s collection of black-and-white photographs eschews spectacle in favour of the everyday. Seedtime, a retrospective of his work on at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town until August 2, is testament to this.

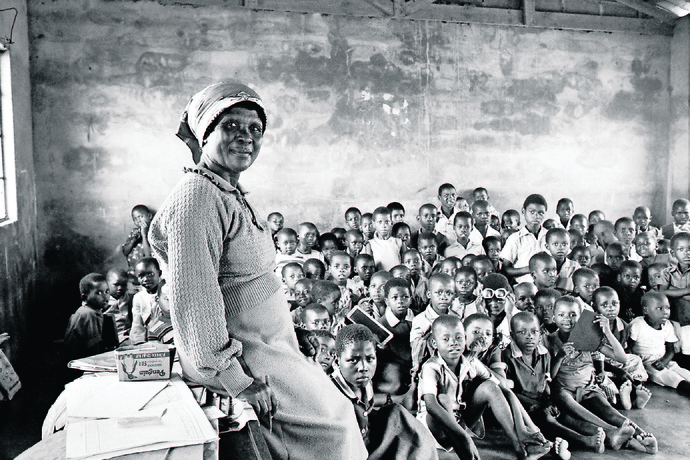

In one photograph, for example, a primary schoolteacher in her mid-50s is seen leaning against a wooden desk, pen in hand. Behind her is a throng of curious young learners. That the school is impoverished is easy to surmise from the children’s bare feet and the absence of any of the usual paraphernalia associated with well-functioning schools – desks, chairs, etcetera. But your eyes are pulled towards the soft face of the teacher, her lips arched in a half-smile. It’s her strength and resilience (not victimhood) that Badsha wants you to see.

I disembark from the train at Woodstock station. Years ago this was a working-class neighbourhood, not too dissimilar to the web of inner-city streets in Durban where Badsha grew up, the Imperial Ghetto as he called it. Now Woodstock is in the spasms of gentrification: the landscape is caught between a past on the threshold of vanishing and a future that is not yet realised.

Badsha is a tall man, bespectacled, with thin gray hair. When he talks, he moves his arms the way a lecturer or a clergyman might to emphasise his point. Another thing about Badsha is that he almost never uses “I” even when talking about himself. He uses “you” – placing the collective above the individual. Indeed, listening to Badsha speak it’s hard to disentangle his own life story from the larger, Âcollective story of the resistance to apartheid.

He was born in 1945 and his father, Ebrahim, a self-taught artist and activist, was a major influence on his life. “He had very little education, formal education,” Badsha says of his father who died in 2003. “Like most of the intellectuals of that period, the artists, they persevered. They saw the importance, or were drawn to, the arts, music, literature, and they created.”

Though his father never exhibited any of his work when he was still alive, Badsha paid tribute to him with an exhibition at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2010 titled Under the Mudoni Tree: The Art of Ebrahim and Omar Badsha. “The act of drawing or writing or playing music is a form of defiance,” Badsha says, reflecting on the lessons from his father’s life. “You’re saying I am human. I am creative. I am worth who I am and, no matter what you do to me, I can create.”

Badsha’s own career as an artist got off to a promising start after he was awarded the Sir Basil Schonland prize. This was in 1965 after his paintings and drawings had been featured in the first nonracial national exhibition – Art South Africa Today. More exhibitions and recognition followed in the ensuing years. In 1966 he featured in an exhibition in Johannesburg titled Artists of Fame and Promise, and in 1969 he won the Oppenheimer award. In 1970 he staged his first solo exhibition in Cape Town at the Artists Gallery. In spite of all the recognition, Badsha says, he made very little money as an artist to support himself.

“If you look after 1960, there were half a dozen [black] writers and even then they called themselves writers but they were working in the newspapers and magazines. They couldn’t make a living as writers. Their books got banned when they were published. The artists, again, there were not more than 20 of us in the whole bloody country who were exhibiting. That’s the cultural legacy of apartheid; there were so few of us. We had no studios or things like that.”

Some, like Badsha’s close friend, the artist Zwelidumile Geelboi MgÂxaji Mslaba Feni – better known as Dumile Feni – went into exile where their careers were arguably more successful. But for those who remained the opportunities to make a living from their art were scant.

Moreover, because most of them were activists, the idea of exhibiting in “whites-only” galleries went against their political inclinations. “There were some who were successful through selling work mainly in Johannesburg. But some of us didn’t want to be part of that system,” Badsha says. “We were political; we were like ‘fuck these people’, we want to create our own audiences. I could have shown all over the world if I had agreed to the government policy. But we said no, any exhibition that is sponsored by the state we will not participate [in it] because it was breaking the cultural boycott and all that ... you were in a no-win situation.”

In 1976, Badsha started taking photographs – but by then his art career had taken a back seat to his political activism. He had been an activist since his high school days in Durban and in the 1970s had a hand in the revival of the Natal Indian Congress. He was also elected as the first general secretary of the Chemical Workers’ Industrial Union.

Three years later the Institute for Black Research, at what was then the University of Natal, published Badsha’s first photographic essay, Letter to Farzanah. The title of the book is taken from a one-page letter Badsha addressed to his daughter in which he expresses his hope and anxieties about the world she had come into. He wrote: “We live in a society in which not a day goes by when we are not called upon to make decisions which tax our commitment and our principles. If we profess to live by our ideals then there is no escape from our situation. Either we follow the dictates of our conscience and remain free, or see ourselves continuously stripped of our self-respect and dignity.”

Consisting of 67 photographs of children – both black and white – juxtaposed with a selection of newspaper articles that zone in on the devastating brutality of apartheid, Letter to Farzanah was banned on its release.

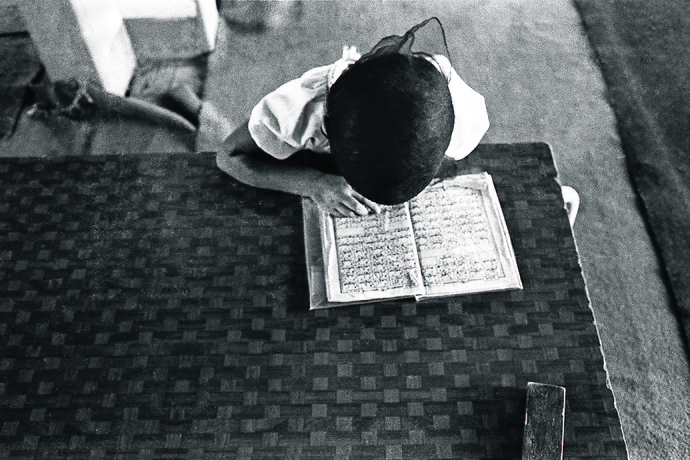

But again, despite the subject matter, Badsha’s photographs are in no way didactic. If there’s one thing that underpins all of his photographs, it’s this refusal to reduce black life to the fact of suffering. One of the most beautiful photographs in Letter to Farzanah is of a young girl at a madrasa. She has her head bowed, reading the Qur’an. You don’t see her face – the photograph is taken from above – but you see her small fingers tracing the Arabic script.

“I think all interesting South African art comes out of some kind of intersection between arts and politics, and the worst stuff comes from the denial of that,” says the writer Imraan Coovadia, a family friend of Badsha. “Omar actually was a trade unionist, [and he] sees his photos as part of his cultural and political ‘work’. And in a way that’s very old-fashioned. And in a way it’s much more radical than most other photographers. I think there are two possible orientations: something like Omar’s, or an orientation towards the European and Anglo-American marketplace.”

“What people forget,” Badsha says, “is that we not only created our art, we [also] had to find a way of creating a new language [of representation] – but we also began to think about our audience. Our audience was not the white middle class. It was there. We exhibited in some places where they [the white middle class] came and bought but we wanted to create a new generation of artists and writers and political activists in our own communities. That was part of the revolution.”

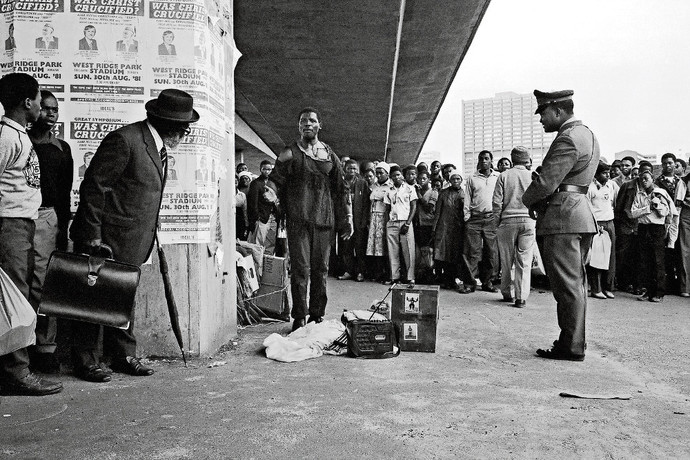

The debates about the representation of black life in South Africa gathered steam in the 1980s, when the country was crawling with foreign photographers and foreign news agencies – Reuters, Associated Press, Agence France Press, to name a few. Images of Casspirs, burning tires, marches and mass funerals circulated around the globe and came to define South Africa during that period.

In her essay Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography, Professor Patricia Hayes says as the country became “big-news from the 1980s onwards, market forces through the press, and outside interests, had started to dictate the kinds of photographs that ‘sold’. This signalled a hardening and proliferation of certain kinds of photography.” But the representation of black South Africans merely as passive victims didn’t sit well with Badsha and many of his contemporaries.

As a response, Badsha got together with a handful of other photographers and activists and founded Afrapix, an independent photo agency, in 1982. The collective took photographs for use by the alternative press and for educational purposes, but they also trained young photographers in townships and staged exhibitions in black communities across the country.

“We were looking for a new way of representing blackness or black life in our communities,” Badsha says.

It was a difficult time to be working as a photographer. “People were dying and people would come to you and say: ‘Comrade, comrade so-and-so died and the funeral is next week. Do you have a photograph of that comrade?’ Things like that. It was quite an extraordinary time.”

In the 1980s Badsha’s reputation as a documentary photographer continued to soar. He released Imijondolo and edited two other seminal collections, Beyond the Barricades: Popular Resistance in South Africa and South Africa: The Cordoned Heart. The latter was part of the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty and Development in Southern Africa and it featured 20 of some the most notable documentary photographers working in the country at the time. Read together, the essays present a stinging critique of apartheid. And in a way they also underline the emergence of documentary photography as a weapon.

“We changed the landscape, the cultural landscape, the photographic landscape, if you look carefully,” Badsha says of the work Afrapix did. “Photography then becomes a major, major artistic form [in the 1980s].”

I ask Badsha, whose work featured in the monumental exhibition Rise and Fall of Apartheid curated by Okwui Enwezor, what he ranks as his proudest achievement. “There’s no such thing as pride, because pride is not what you’re out there to do,” he says.

“You do what you have to do because you have to do it. Because it’s for your own sense of self-worth and survival. You’re part of a movement. You don’t think about pride or big prizes or world renown or anything. You’re just one of many ”¦ you were bearing witness and providing a voice.”