Timbuktu, French Tombouctou, is a city in the western African country of Mali. Often used as a popular term to describe a distant and mystical place, the city of Timbuktu was historically significant as an area of vibrant trade. In the 12th century, slaves and goods such as salt, gold, and ivory were among the prime commodities traded.

This lesson will concentrate on trade across the Sahara Desert, focusing on why Timbuktu became the centre of trade, what kind of goods were exchanged, the spread of Islam from North Africa into West Africa, the importance of camels as a means of transportation, and the enormous scale of the trade route.

The second part of this lesson will focus on the Kingdom of Mali at the height of its power under the leadership of Mansa Musa. The influence of Islam on Musa’s leadership will be highlighted by concentrating on his pilgrimage to Mecca and the construction of the Great Mosque. Finally, the lesson will explain why Timbuktu was not only a centre of trade, but also a centre of learning and why it is now considered a World Heritage site.

Flag of Mali. Image source

Flag of Mali. Image source

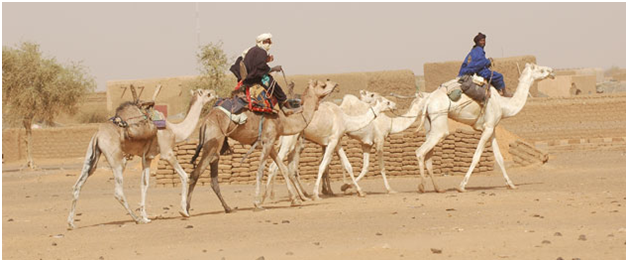

Riding Camels in the Sahara Desert. Image source

Riding Camels in the Sahara Desert. Image source

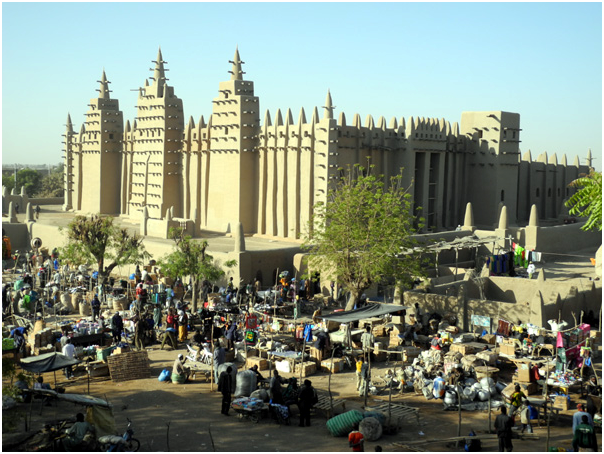

"The Great Mosque in Djenne, the largest Mud- Brick Building in the World” . Image source

"The Great Mosque in Djenne, the largest Mud- Brick Building in the World” . Image source

Trade across the Sahara Desert

Camel caravans as the means of transport

Traders moved their goods across the Sahara in large groups called caravans. Camels were the main mode of transportation and were used to carry goods and people. The camel was the most important part of the caravan. Without the camel, trade across the Sahara would have been impossible. Camels are uniquely adapted to survive long periods without water. They can also survive large changes in body temperature allowing them to withstand the heat of the day and the cold of night in the desert.

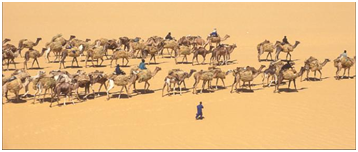

A camel caravan moving through the Sahara desert. Some of these caravans will start walking from 4 am until sunset to trade goods with others . Image source

A camel caravan moving through the Sahara desert. Some of these caravans will start walking from 4 am until sunset to trade goods with others . Image source

Sometimes slaves carried goods as well. Travel by camel caravan was slow, strenuous, and dangerous. Hazards such as excessive heat, stifling sandstorms, death by starvation, thirst, and attacks by raiders added to the possibility of getting lost. Despite all this, trans-Saharan trade along caravan routes linking oases persisted from very early times. The Silk Roads were already in use in the late Bronze Age, though intensive use of cross-desert roads was triggered by the domestication of the camel. Caravans included on average a thousand camels, sometimes reaching as many as 12 000 animals. Runners were sent ahead to oases to ship out water when the caravan was still days away. Large caravan processions were safer because they offered protection from bandits. Today most cross-desert transport is through an extensive tarmac road network in addition to transport by air and sea. Tuareg camel caravans still travel on the traditional Saharan routes, carrying salt from the desert interior to communities on the desert edges.

Goods including salt brought from Europe and North Africa into Mali where they were exchanged for gold, slaves, ivory and ostrich feathers

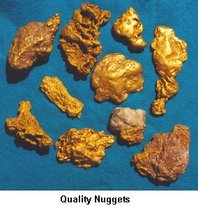

In the ancient empire of Mali, the most important industry was the gold industry, while the other trade was the trade in salt. Much gold was traded through the Sahara desert to the countries on the North African coast. The gold mines of West Africa provided great wealth to West African Empires such as Ghana and Mali. Other items that were commonly traded included ivory, kola nuts, cloth, metal goods, beads, and also human beings in the slave trade.

Salt (pictured below) was often brought from Europe and North Africa in exchange for Gold (pictured above), or other commodities such as slaves or ivory. Image source

Salt (pictured below) was often brought from Europe and North Africa in exchange for Gold (pictured above), or other commodities such as slaves or ivory. Image source

Gold was bountiful in West Africa, and was used as a form of currency. It was also used by the wealthy as decoration, worn on articles of clothing, and it was prized by many people. Worldwide, African gold was famous and many countries wanted it, and would trade for it. The trade in gold helped Mali stay very wealthy. The main item they would import was salt which they would use it for many things. Since salt was abundant in the North of Mali, but scarce in the South, they would have to import it. Salt was mainly used to preserve foods, like meat, but also corpses, etc. Malians would also need salt in their food, since they wouldn't normally have much in their diet. They would also import things like glass, ceramics, and precious stones from North Africa.

The spread of Islam across North Africa and into West Africa via traders during the 9th century

Islam had already spread into northern Africa by the mid-seventh century A.D., only a few decades after the Prophet Muhammad moved with his followers from Mecca to Medina in the neighbouring Arabian Peninsula. While the presence of Islam in West Africa dates back to the 8th century, the spread of the faith in North Africa was a gradual and complex process. Islam slowly spread to regions that now make up the modern states of Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali and Nigeria. Much of what we know about the early history of West Africa comes from medieval accounts written by Arab and North African geographers and historians. It is apparent that the early presence of Islam in West Africa was linked to trade and commerce with North Africa. Although trade between West Africa and the Mediterranean predated Islam, North African Muslims intensified the Trans-Saharan trade. North African traders were major players in introducing Islam into West Africa. Between the 8th and 9th centuries, Arab traders and travellers, and thereafter African clerics, began to spread the religion along the eastern coast of Africa and to western and central Sudan.

The first converts to the religion were Sudanese merchants, followed by a few rulers and courtiers. The masses of rural peasants, however, remained relatively untouched. In the 11th century, the Almoravid intervention, led by a group of Berber nomads who were strict observers of Islamic law, gave the conversion process a new momentum in the Ghana Empire and beyond.

The history of Islam in West Africa can be divided into three stages: containment, mixing, and reform. In the first stage, African kings contained Muslim influence by segregating Muslim communities; in the second stage African rulers blended Islam with local traditions as the population selectively appropriated Islamic practices; and finally in the third stage, African Muslims pressed for reforms in an effort to rid their societies of mixed practices and implement Sharia law.

The kingdom of Mali

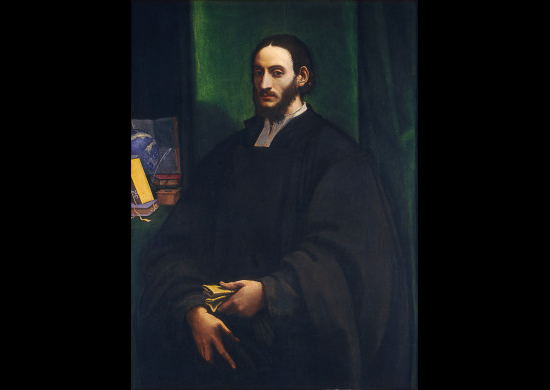

A depiction of Mansa Musa in the 14th century. Image source

A depiction of Mansa Musa in the 14th century. Image source

Mali at the height of its power under Mansa Musa in the early 14th century

Mansa Musa made an important mark in Mali by introducing the kingdom to Islam and making it one of the first Muslim states in northern Africa. He incorporated the laws of the Quran into his country’s justice system. Cities such as Timbuktu and Gao were developed into international centres of Islamic learning and culture. Elaborate mosques and libraries were built. The university that emerged in Timbuktu might well have been the world's first. The cities became meeting places for poets, scholars, and artists. Musa became one of the most powerful and wealthiest leaders of his time. Mali became renowned in the imaginations of European and Islamic countries in the 14th century.

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca

A camel caravan moving through the Sahara desert. Some of these caravans will start walking from 4 am until sunset to trade goods with others . Image source

A camel caravan moving through the Sahara desert. Some of these caravans will start walking from 4 am until sunset to trade goods with others . Image source

Musa is most noted for his pilgrimage to Mecca, a visit which put Mali on the map. In 1339, Mali appeared on a “Map of the World” after his pilgrimage. In 1367, another map of the world showed a road leading from North Africa through the Atlas Mountains into Western Sudan. In 1375 a third map of the world showed a richly attired monarch holding a large gold nugget in the area south of the Sahara. Also, trade between Egypt and Mali now flourished.

On his return from Mecca, Musa brought back with him an Arabic library, religious scholars, and architects; who helped him build royal palace universities, libraries and mosques all over his kingdom. He strengthened Islam and promoted education, trade, and commerce in Mali. He laid the foundations for Walata, Jenne, and Timbuktu to become the cultural and commercial centre of North Africa.

Mansa Kankan Musa ruled with all the ideals of a fine Muslim king. He died in the mid-14th century, and Mali was never quite the same. Internal squabbling between ruling families weakened Mali's governance and its network of states started to unravel. Then, in 1430, a group of Berbers seized much of Mali's territory, including Timbuktu.

Construction of the Great Mosque

The Great Mosque of Djenné, the largest mud- brick building in the world. Image source

The Great Mosque of Djenné, the largest mud- brick building in the world. Image source

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the largest mud brick building in the world and is considered by many architects to be the greatest achievement of the Sudano- Sahelian architectural style, albeit with definite Islamic influences. Originally built in the 13th or 14th century, reconstruction of the current Great Mosque began in 1906 and was probably completed between 1907 and 1909. The mosque's construction was supervised and guided by the head of Djenné's mason guild, Ismaila Traoré. At the time, Djenné was part of the colony of French West Africa and the French may have offered political and economic support for the construction of both the mosque and a nearby madrasa. The structure of the small town of Djenné is demarcated by rivers with approximately a population of 23,000, and it’s close to 2,000 houses mostly retaining Malian traditional styles.

The city of Timbuktu

A portrait of Al-Hasan ibn Muhammad Al-Wazzan, known as Leo Africanus in the West. Image source

A portrait of Al-Hasan ibn Muhammad Al-Wazzan, known as Leo Africanus in the West. Image source

Leo Africanus’s eyewitness stories of his travels and Descriptions of Timbuktu in his book Description of Africa (1550)

For centuries caravan travel was the central means of transportation for goods traded between the Mediterranean and the Sudan. Cloth, salt, metals, pearls and writing paper were brought from Europe and the Maghreb into present-day Mali, where they were exchanged for gold, slaves, ivory and ostrich feathers.

The last caravan routes were closed down in 1933. Leo travelled along these caravan routes, into the Saharan desert and twice to Timbuktu; once as a young man, accompanying his uncle to visit the sultan of the Sudan; and once a few years later, on a longer trip through what was then known as "Black Africa".

Below you will find Leo Africanus’s description of Africa and specifically Timbuktu as written around 1492.

“The name of this kingdom is a modern one, after a city which was built by a king named Mansa Suleyman in the year 610 of the hegira around twelve miles from a branch of the Niger River. The houses of Timbuktu are huts made of clay-covered wattles with thatched roofs. In the centre of the city is a temple built of stone and mortar, and in addition there is a large palace, constructed by the same architect, where the king lives. The shops of the artisans, the merchants, and especially weavers of cotton cloth are very numerous. Fabrics are also imported from Europe to Timbuktu, borne by Berber merchants. The women of the city maintain the custom of veiling their faces, except for the slaves who sell all the foodstuffs. The inhabitants are very rich, especially the strangers who have settled in the country; so much so that the current king has given two of his daughters in marriage to two brothers, both businessmen, on account of their wealth. There are many wells containing sweet water in Timbuktu. Grain and animals are abundant, so that the consumption of milk and butter is considerable. But salt is in very short supply because it is carried here from Tegaza, some 500 miles from Timbuktu. I happened to be in this city at a time when a load of salt sold for eighty ducats. The king has a rich treasure of coins and gold ingots.

The royal court is magnificent and very well organized. When the king goes from one city to another with the people of his court, he rides a camel and the horses are led by hand by servants. If fighting becomes necessary, the servants mount the camels and all the soldiers mount on horseback. When someone wishes to speak to the king, he must kneel before him and bow down; but this is only required of those who have never before spoken to the king, or of ambassadors. This king makes war only upon neighboring enemies and upon those who do not want to pay him tribute. When he has gained a victory, he has all of them--even the children--sold in the market at Timbuktu.

Only small, poor horses are born in this country. The merchants use them for their voyages and the courtiers to move about the city. But the good horses come from Barbary. They arrive in a caravan and, ten or twelve days later, they are led to the ruler, who takes as many as he likes and pays appropriately for them.

The title page of 'A Geographical history of Africa' by Leo Africanus. Image source

The title page of 'A Geographical history of Africa' by Leo Africanus. Image source

The king is a declared enemy of the Jews. He will not allow any to live in the city. If he hears it said that a Berber merchant frequents them or does business with them, he confiscates his goods. There are in Timbuktu numerous judges, teachers and priests, all properly appointed by the king. He greatly honours learning. Many hand-written books imported from Barbary are also sold. There is more profit made from this commerce than from all other merchandise.

Instead of coined money, pure gold nuggets are used; and for small purchases small cowry shells carried from Persia.

The people of Timbuktu are of a peaceful nature. They have a custom of almost continuously walking about the city in the evening (except for those that sell gold), between 10 PM and 1 AM, playing musical instruments and dancing. The citizens have at their service many slaves, both men and women.

The city is very much endangered by fire. At the time when I was there on my second voyage, half the city burned in the space of five hours. But the wind was violent and the inhabitants of the other half of the city began to move their belongings for fear that the other half would burn.

There are no gardens or orchards in the area surrounding Timbuktu.”

Timbuktu as a trade centre on the trans-Saharan caravan route

The Trans-Saharan trade route was conducted throughout a vast region between the Mediterranean countries and sub-Saharan Africa. It was an important trading route commencing from the early 8th century to late 16th century. As a place where countless numbers of people practised trade; the Sahara was surrounded by many small trading routes. The establishment of trade interconnected the Europeans to the African empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. However, travelling across the Sahara was difficult; transportation relied and gravely depended on camels.

In 1235, the Ghana Empire collapsed and the Islamic Mali Empire ascended to rule. Due to the strong Muslim push at the time, many of Ghanaians converted to Islam. Though the gold-salt trade continued to linger, a second major gold-salt trade route emerged. This route weaved through the Sahara and continued into Egypt’s interior. As both routes thrived, the growing impact of Egypt’s culture extended throughout Sudan. Under the Mali Empire, wealthy towns proliferated. Particular cities such as, Gao and Djenné, of the Niger bend developed with great prosperity. As for Timbuktu, it became widely known as a city of fortune. The growth of the Mali Empire led to an extension of the region into the Savannah and forest. Western routes were developed and with that, cites such as Ouadane, Oualata, Chinguetti, Begho, and Bono Manso emerged along important trading routes.

The Portuguese expeditions from the West African coast created new routes for trade between Europe and West Africa. European bases on the coast were established late in the 16th century. As the Saharan route was a treacherous route, it resulted in a weakening of political and economic influence in North Africa. In 1591, the Moroccan War devastated Timbuktu and Gao, the significant trading centres. The outcome of the war reduced trade significantly. The trans-Saharan trade routes still continued after the war. After the French invasion railroads were constructed and West African trade routes became dominant. From the mid-20th century various nations were granted independence.

Askiah Muhammad’s Reign

Goods coming from the Mediterranean shores and salt being traded in Timbuktu for gold

From the 11th century and onward, Timbuktu became an important port where goods from West Africa and North Africa were traded. Goods coming from the Mediterranean shores and salt were traded in Timbuktu for gold. Salt, books and gold were the main commodities that were traded in Timbuktu. Salt was extracted from the mines of Tegaza and Taoudenit in the north, gold from the immense gold mines of the Boure and Banbuk and books were the refined work of black and Arabs scholars.

Timbuktu had been an important trans-Saharan trade route. Goods coming from Mediterranean shores and salt from central Sahara were exchanged in Timbuktu for gold. The prosperity of Timbuktu attracted both African scholars and Arab traders from North Africa.

Pictured above are gold nuggets that were exchanged with salt/ or other commodities. Image source

Pictured above are gold nuggets that were exchanged with salt/ or other commodities. Image source

The specialization of Timbuktu was in knowledge and book trade. [This is according to the CAPS curriculum and does not solely focus on Muhammad’s reign]

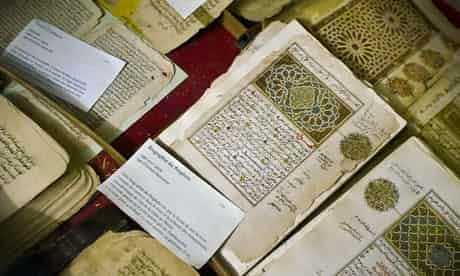

Under the reign of Askia Muhammed (1493-1591), Timbuktu became an important centre for Islamic learning, engineering, medicine and architectures. With the campuses of Sankore Madressah (comparable to an Islamic University) attended by some 25,000 students, Timbuktu became an intellectual and religious centre and served as a distribution platform for scholars and books. Books were not only written in Timbuktu, but they were also imported and copied there. There was indeed a local book-copying industry in the town.

Hundreds and thousands of manuscripts were written over the course of the centuries. Written in ornate calligraphy, the manuscripts represent a compendium of learning on everything from law, sciences and medicine to history and politics. It is reported that Timbuktu made more profit from the trade in books than from any other line of business.

Timbuktu as a centre of learning

Mathematics, chemistry, physics, optics, astronomy, medicine, history, geography, the traditions of Islam, government laws and much more

Some of the 20,000 ancient manuscripts at the Ahmed Baba Institute. Photograph: Ben Curtis/AP. Image source

Some of the 20,000 ancient manuscripts at the Ahmed Baba Institute. Photograph: Ben Curtis/AP. Image source

The Golden Age of Islam is traditionally dated from the mid-7th century to the mid-13th century. During this period Muslim rulers established one of the largest empires in history. “In Timbuktu there are numerous judges, scholars and priests, all well paid by the king, who greatly honours learned men. Many manuscript books coming from Barbary are sold. Such sales are more profitable than any other goods,” wrote Leo Africanus in the 16th century. During this period, artists, engineers, scholars, poets, philosophers, geographers and traders in the Islamic world contributed to agriculture, the arts, economics, industry, law, literature, navigation, philosophy, the sciences, and technology, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding inventions and innovations of their own. Also at that time the Muslim world became a major intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education.

Although mosques like Sankoré were centres of learning, much of the day-to-day teaching activity occurred more informally in the homes of scholars. The core of the Islamic teaching tradition is the transmission of texts, which is handed down through a chain of transmitters from the teacher to the student, preferably through the shortest and most prestigious set of intermediaries. The student would listen to the teacher’s dictation, write their own copy and read it back, or listen to another student read it. The scholars had their own private libraries to help them teach.

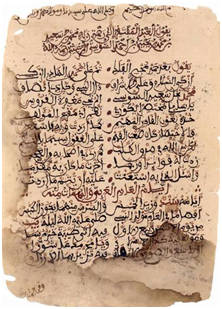

Timbuktu Manuscripts Project and South African collaboration

The city and its desert environs are an archive of handwritten texts in Arabic and in African languages in the Arabic script, produced between the 13th and the 20th centuries. The manuscript libraries of Timbuktu are significant repositories of scholarly production in West Africa and the Sahara. Given the large number of manuscript collections it is surprising that Timbuktu as an archive remains largely unknown and under-used.

Pictured above is an example of a deteriorating manuscript. The Timbuktu Manuscript Project aims to preserve the content contained within these manuscripts. Image source

Pictured above is an example of a deteriorating manuscript. The Timbuktu Manuscript Project aims to preserve the content contained within these manuscripts. Image source

The manuscripts provide a written testimony to the skill of African scientists, in astronomy, mathematics, chemistry, medicine and climatology in the Middle Ages.

South Africa is driving a project to build a new library to house between 200 000 and 300 000 ancient manuscripts currently housed in 24 private libraries in and around the Malian city, and to train local librarians in the preservation of a treasure trove that is threatening, literally, to disintegrate. Launched in 2003, the South Africa-Mali manuscript project was the first official cultural project of the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), the socio-economic development plan of the African Union. The Timbuktu Manuscripts, or Mali Manuscripts, some of which date back to the 13th century, are Arabic and African texts that discuss the city's glorious past; when Muslim merchants would trade gold from West Africa to Europe and the Middle East in return for salt and other goods. The manuscripts point to the fact that Africa has a rich legacy of written history, contrary to the popular notion that oral traditions alone preserved the continent’s heritage. A South Africa-Mali Timbuktu Manuscripts Project was officially launched in 2003 and a major achievement of this project was the new library-archive building, which was inaugurated in Timbuktu in January 2009.

Why Timbuktu is a World Heritage Site

Recognising its significance as a site of African architecture and of its scholarly past, UNESCO declared Timbuktu a World Heritage Site in 1990. Timbuktu was a thriving centre of scholarship instrumental to the spread of Islam in Africa. It retains three notable mosques and one of the world’s great collections of ancient manuscripts. This West African city, long synonymous with the uttermost end of the Earth, was added to the World Heritage List in 1988, many centuries after its apex. Timbuktu can be seen as an intellectual and spiritual capital and a centre for the propagation of Islam throughout Africa in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The criteria for declaring Timbuktu as a heritage site have been described as; a) interchange of values, (b) icon of an era and (c) interaction with the environment.

The Mosques of Mali and holy places of Timbuktu have played an essential role in the spread of Islam in Africa at an early period. The three great mosques of Timbuktu, restored by the Qadi Al Aqib in the 16th century, bear witness to the golden age of the city at the end of the Askia dynasty. The three mosques and mausoleums are outstanding examples to the urban urbanisation of Timbuktu.

Although continuously restored, these monuments are today under threat from desertification as radical Islamists, known as Ansar Dine, have taken over the small city in Mali, threatening destruction to monuments, religious sites, and priceless documents. Tourism has suffered from years of security problems. Gunmen seized three foreigners and killed a fourth on a street in Timbuktu last November. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) claimed responsibility.