Published date

Related Collections from the Archive

From the book: A.I. Kajee His Work for the Southern African Indian Community by C. H. Calpin

And so indeed it was.

Kajee was on the way out. His hair was already grey. Now his face was grey, with the greyness that an Indian's face assumes in sickness, like the bloom on a black grape.

He was working with the demonic energy of a man to whom time had become the only wealth worth possessing. He knew something of the despair that Cecil Rhodes knew, an almost universal despair of men who know the impulse of creative work.

He had a slight diabetic stroke. His doctors ordered him a long rest, prolonged treatment and undisturbed quiet. One side of his face was slightly contracted. One of his eyes was a little closed. But his mind was as lively as ever, too lively for this condition and too stimulated by the friends who came to see him.

Indians have a gratifying concern for one of their fellows who is sick, and 28 Ryde Avenue became a sort of Mecca to which his friends made their pilgrimage either in body or in spirit.

The most endearing feature about Kajee was his capacity for friendship. Where other men choose their friends from a small group of acquaintances in a particular class, Kajee knew the friendship of people in all ranks of society and among all races. Kajee had magic in him. You couldn't meet him without being attracted by his magic, his striking face and eyes, his voice and gestures, his conversation and his all embracing affection. He would weep with you and laugh with you; he would fight with you and fight for you, if you were willing to let him. To many he was a friend indeed. To them his memory is surely golden in every sense.

Among his closest and dearest friends were those who were not much interested in politics and who stood by him with quiet confidence, ready when he needed them. For months he did not see them, so busy was he in his affairs. I am thinking of people like "Banja Bobat" and Suliman Paruk, men who had grown up with him and had chosen to live simple lives outside the hurly burly of public life. To them he turned in deep affection at those moments when he looked for calm advice and serious help. To the end of his life they were brothers to him. Then there were other friendships of a different order though of the same worth. Younger men by a few years, in Essop Randeree and Sol Paruk, the sort of men who would go anywhere, do anything, for him and for whom; he would go anywhere and do anything. The younger rebels often sneered at the attachment of such men. Little did they know of friendship? Included too were his business associates, the most recent of whom was A. B. Moosa, but amongst whom must be mentioned the shrewd M. A. Motalla. There were a host of these, some of more critical vein like A. M. Moolla with whom he often strove in discussions, and upon whom he relied for the critical judgment which some of the others could not supply and which was so necessary to him in his political work.

But best of all perhaps were those who loved him and did not care a jot for his politics or for his affairs, the countless ordinary people whom he had known in childhood or whom he had got to know during his life. His house was open to them all, young and old. Nor were they confined merely to Indians. Kajee is the only Indian I know who could move with grace and distinction from the east to the west. He was, in fact both a westerner and an easterner, changing from one idiom to the other with ease and delight, laughing easily and talking fluently, throwing himself into rollicking ornamentations of incidents as attractively as a boy, and passing into the most profound discussions when occasion arose. He counted among his European friends many men of improved minds and of various vocations. Among them were General Smuts, Sir Evelyn Baring, Mr. J. H. Hofmeyr, and Mr. Justice F. N. Broome. There is good reason to know that these men had held him in respect and even affection. For one thing he appealed to them as a man of the world and as a man of affairs. He knew more about the Indian problem in South Africa than any other man in the world, not excluding General Smuts.

He was the only authority in the world on this particular problem. He could meet South Africa's public men therefore and feel quite at ease. At times some of them who were not notable for sympathy with the Indian cause were often worsted at his hands in a recapitulation of facts on which they proved astonishingly ignorant.

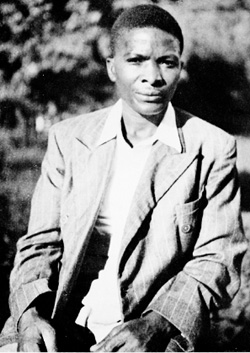

"John" - the faithful servant

"John" - the faithful servant

The men I have mentioned were men of improved minds, in the presence of whom he learnt much. The esteem in which he held Mr. Justice Broome, for example, was a tribute to both, for in many ways they were men of contradictory natures and outlook having but one thing in common, an earnest desire to pursue the truth.

It is a big claim for him that he was the only authority on the South African Indian problem. There have been many Indians who have devoted themselves to some aspect of Indian welfare and who deserve the gratitude of a community singularly inarticulate in gratitude. But Kajee knew all aspects of his people's affairs. There was nothing he did not know.

There were other things that set him apart from his fellows. To use a current expression, Kajee 'Had something' that is not given to all men. No European met a without recognising it. He counted among Europeans many enemies and many more friends. He always acknowledged the benefits he had received by being in their company. There are many people I could mention of whom he often spoke, and one more particularly than others is Mr. J. W. Meldrum, the secretary to the High Commissioner for India, whose critical assessments of Kajee's views and policies did much to sharpen the intellect.

One of the secrets of Kajee's success which is worth passing on to any young Indian desirous of similar success was the fact that he knew his opponents' case as well as his own. He never allowed his knowledge to weaken his arguments or to divert him from the ends he set. Instead he used this knowledge to fortify the Indian 'It is one of the weaknesses of many present leaders of the Indian community that they are ignorant first of their own history and secondly of the European case. We live in an age; it is true, when noise serves for knowledge, and when the loudest voice is substitute for wisdom. The world has been brought low by the vociferous chancer. For the most part we are governed by the groundlings but the time will come again when ability and merit, knowledge and wisdom will be needed to put right what the rabble has put wrong. Then the Kajees will be needed, the men who combine the adventure of public affairs with the ability and knowledge to lead the illiterate masses.

This feature which was so marked in him of studying and knowing the context in which Europeans moved was a tremendous help to him in all his public work. The influence of individual Europeans upon him was great. One of the most abiding friendships which he knew was that of a European woman Mrs. Pauline Morel, the headmistress of an Indian school in Durban. To her he owed so much in so many ways that it is quite impossible for any narrator to catalogue his debt. This friendship cannot be described in any other terms than those of beauty. In his private life Kajee was a complex character, a man of many moods, of sharply rising temper and short periods of depression. The friendship of Mrs. Morel brought into his life, not only a wealth of good counsel but a kindliness for him and those near him which made smooth many difficult periods. Kajee was not always as sympathetic with his own as he was with others, and it was in these periods when the smaller things went wrong that Mrs. Morel brought to him a womanly wisdom for which he was always grateful.

It is always difficult to read the mind of another. In many ways Kajee was a singularly shy fellow. In many other ways he was attractively vain. This mixture of shyness and vanity was best seen on those occasions when he was entertaining some new visitors to his house. Many travellers sought him out, authors and foreign corresÂpondents of newspapers. People like Negley Farson and Stuart Cloete. They would come to Ryde Avenue, and Kajee would greet them in a shy manner and preen himÂself a little, like a small boy, when they remarked about the pleasant lounge, and he would take them into dinner rather proudly, certain that John would serve up the food in the correct manner. He rejoiced in these meetÂings and in the exchange of reminiscences and opinions.

He had the mind of an historian. His reading was wide and catholic. He read every newspaper published in. South Africa, from the Guardian to the Star. He knew journalists and editors throughout the country. He was either at war with them or at peace. Many are the reporters who have reason to bless him for the way he would provide them with copy when copy was difficult to obtain. He acted for a long time as a sort of voluntary correspondent of the Bombay chronicle to which he sent the most amazing cable "Press collect". He kept up a voluminous correspondence with all manner of people about all sorts of things. He seldom read a novel. The booksellers had a fixed order to choose for him anything they thought might interest him. He must have been one of their best customers. It was not that he paid no attention to novels. Indeed there were always a few by his bedside. He picked them up at odd moments, for he was the sort of man who could read an average length novel in half an hour or so. Most of his reading was confined to subjects bearing upon his immediate interests. He liked studies of American life. He was an avid reader of biographies. There was not a blue book on any subject relating to non-Europeans in South Africa that he did not study and to which he did not add his marginal notes.

Kajee had no idea of the meaning of leisure. What he did know was that a change of scene even with extra work was a holiday. He was stimulated by new aspects of his own work, the travel which work entailed and he was always excited, like the boy he was, at the prospect of going a train journey or flying to some other place. Movement was the breath of life to him. He always said he wanted to go to Switzerland. But then he wanted to go to South America. But now Kajee was ill. His face had the lines of sickÂness imposed upon the lines experience and character had drawn. It was obvious if Kajee lived it would be a very different Kajee that rose from his bed. Kajee was restless in bed as out of it, and within a couple of weeks he was persuaded to go into the country to escape the importunities of those who looked to him for counsel and help. He went to stay with another dear friend, Cassim Lakhi at Greytown. Cassim Lakhi had the things which Kajee needed at this time.

Cassim Lakhi had spent many years as a student in England. His house at Greytown is distinguished for a library, its music, and its pictures. There are few Indians who live the sort of life that surrounded this Greytown home. It was the sort of change Kajee needed, restful and quiet, orderly and satisfying. Here in good company Kajee's spirits rose. He had his close friends around him. There was old Mahomed Ebrahim, who in Muslim circles was well known for his cooking. Mahomed prepared special meals. Others of his friends accompanied him on short walks or sat chatting in the garden. This was a time of great solace. The telephone, on which for 25 years he had lived, was forbidden. Others took incoming calls and the callers diverted to their own business. The office at Albert Street was far away. The cares of business and politics receded, and Kajee remembered the things worth remembering, his boyhood days.

A man, they say, goes home to die. A man certainly finds his own when he knows he is dying. I do not think Kajee ever knew a matter of personal habits until this time. Driven by ambition and impelled by purpose to spend his days tearing himself and others in a host of activities. It was at Greytown he began to know himself and to be reminded that there was in the world such a thing as happiness. He might have recovered completely had he been able to resist the importunity of his friends and to silence the call which always urged him in the service of the Indian community. He went from Greytown to a friend at Bulwer for a few days, and from there on a sudden call from a friend in difficulties in Durban he hurried back home. Once more Ryde Avenue became the centre of his industrial and energy. He worked himself up to such great passions in some personal trouble confronting one of his friends, and at the same time was tempted once more to make a last effort on behalf of his community to see Mr. H. G. Lawrence who, as we have seen, had just returned from the United Nations. Against the advice of those near him he travelled to Cape Town by air where he stayed at his flat on the top floor above the Avalon Theatre in Hanover Street. At Cape Town he went to a specialist who confirmed all his fears.

"There will be no second chance," the specialist said. Kajee had had a number of previous warnings as early as 1946. Some of his doctor friends had indicated the course he must travel if he wished to retain his health and usefulness. A specialist in Johannesburg had added his diagnosis of Kajee's condition. He knew that unless he gave up the struggle, the struggle would destroy him. To the pleadings of his family and friends he always made one answer. "I shall retire from politics and business as soon as a round table conference is arranged." At this time Mr. H. G. Lawrence, himself a man overburdened with work and by no means well, was staying at George. Kajee travelled there in order to see him, and while waiting for his appointment he spent a few days with one or two friends and acquaintances on holiday in this the most beautiful part of the country. Kajee used to say that he would like to die in the Knysna district. His friends were all keen on sea fishing and would take Kajee with them. Here again, as at Greytown, he disÂcovered what he had been missing all these years, in leisure and recreation.' The friends he was with were the sorts of people to be found in any society who take opportunities to enjoy themselves in simple ways. It seldom occurred to Kajee to go fishing. Or indeed, to do anything in the way of bodily or mental diversion. He enjoyed the pictures, but since his very young days as a footballer he took very little exercise and was never seen taking part in any of the games or activities which attracted a few of his friends. At George however, he recaptured once again something of his boyhood, as far as his physical condition would permit.

The day came when he met Mr. H. G. Lawrence for an interview at the Magistrates Court. He had his notes with him. Poor Kajee. He was talking, exchanging views with this minister to whom he was much attached, when a sharp attack caught him. His sight became blurred. He went on talking clumsily for a few moments, trying to regain his composure and to collect his thoughts. He could not bear to embarrass Mr. Lawrence, and after a minute or two he pushed his notes towards Mr. Lawrence I begged him for a glass of water. He had been talking on the best way in which he could help to forward the proposal to hold a round table conference. His political life might be said to have begun with a round table conference in 1926. His life was to end with a plea that another round table conference should be held.

He had recently had some discussions with General Smuts. The Prime Minister and he had come to the same conclusion. General Smuts informed Mr. Lawrence by telegram to see Kajee. The Natal Indian Organisation was to hold a conference at Durban on January 8th and Mr. Lawrence had agreed to open the Conference. Kajee's purpose was to talk over the approach Mr. Lawrence might make in his speech to the subject of a round table conference. They were talking about this when Mr. Lawrence noticed that Kajee was ill. He suggested that Kajee should see Dr. Mann, who occasionally had been brought in to check the health of General Smuts. Mr. Lawrence proposed that Kajee should go over and see him there and then, and afterwards join Mr. Lawrence at his hotel where they could continue their chat. Mahomed Paruk was with Kajee at the time, and they went out together to the car to be taken over to Dr. Mann's rooms. Getting out of the car Kajee's sight be-blurred. He leaned heavily upon his friend who helped him into the Doctor's house. Reaching there his lagged beneath him and he was placed on a settee.

Before the Doctor had time to apply his stethoscope Kajee was heard to repeat a few prayers in Arabic. As he did so he turned over and died.

As tenderly as if bearing a General, his friend Mohamed Paruk had his body taken to the hospital. There it lay until Sol Paruk and others motored from Cape Town. Mr. Lawrence was able to arrange for his friends to telephone quickly to Cape Town and Durban. Next morning, they placed his body in the garden shortly before sunrise and waited for the dawn, at the first sight of which they said their funeral prayers over him. Here within the range of the Outeniqua mountains, where a day before he had said he would like to die and be buried, a few rose trees bent in the morning breeze.

It is a simple enough story; from then on all the confused issues surrounding Kajee were straightened out as neatly as the sunrise. He had arranged to return to Durban by air, and so he came by air. His small frame was laid on the floor of one of the rooms at 136 Mansfield Road, surrounded by his women relatives, as is the custom of Islam. They sat praying silently over him, sprinkling camphor on his chest. His wife was in India at the time on a visit. I went to see him there. What a small coffin, I thought.

Kajee was buried as a Muslim. His coffin, headed by the white bearded and majestic looking Molvi crowded about by his friends was carried down the Old Dutch Road, along Grey Street to the Mosque, and from there to the cemetery at Brook Street. His friends, surging about the coffin, took turns in carrying him a few steps on his way. At long last they carried him, as he, for so long, had carried them, while from the housetops, the shops, and the blocks of flats Indians, their women and children, looked upon this strange and moving spectacle, and in the crowd that followed a few Europeans joined the procession.

So passed Abdulla Ismail Kajee.

The ways of estimating a man's worth are legion.

Two days before he died, he with Mohamed Paruk, called on an old Irish doctor. It was almost as if Kajee was trying to discover some Doctor who would give him hope as to his condition, so numerous were the medical had consulted.

Are you any relation to A. I. Kajee?" the Doctor asked him.

The two men smiled and Mohamed Paruk playfully interpreted the remark, "No, he is no relation to A. I. Kajee."

Pity," observed the Irishman. "Great man, A. I. Kajee.

We need more men like him."

When the Doctor was told that he was examining the Kajee, he said, "You are too sick a man to get better. Pity a short time after his funeral the Prime Minister received a deputation of Natal Indian Organisation at Pretoria. At the outset General Smuts spoke of Kajee delegates in terms of affection and esteem. He and the Indian delegates with him stood in silence for a few moments in Kajee's memory. General Smuts had watched so many of his fellows younger than he depart this life. He was often called upon for such occasions as he provided at this interview. It is very satisfying to know in life the friendship of a man like General Smuts. Such friendship offered without good reason.

Measuring Kajee's achievements perhaps the best memorial that can be raised is the inspiration he leaves to a community which at times lack inspiration.

The Indian community is entering a new era in its affairs. As I suggested at the beginning of this appreciation of Kajee, his death marked the end of a particular period in relations between Indians and Europeans. An entirely new order is opening. The new Indian leader is a product of the class war. He is a part of the revolutionary change. Indeed he is a revolutionary. Inside the Indian community there is no man to take Kajee's place. The destiny of the Indian community rests almost entirely on the choice of leaders and the man they choose to follow. At the moment they appear to have chosen to attach themselves to the new ideology that is sweeping the world, if the noise with which their leaders blazon the new truths is any criterion of their opinions.

Kajee was never ignorant of the forces moving in the world, and he knew better than most men where the Indian community might go under the influence of a younger generation of politicians raised in the militant schools of communism. He was only too fully conscious, as many of us are who have lived through two world wars, of the disappearance of systems and orders and the rise of other ideas. But just as he in his early manÂhood recognised the contribution of a generation of older men who preceded him, so too will the younger generÂation of leaders come one day to recognise his contribution both to his community and to his country. For Kajee was a great South African patriot, even as he was a great South African Indian. The day is not past I hope, when patriotism too is also despised. Kajee was the single Indian who can be described as an Indian South African. As such his spirit will continue to inspire the men of this and of future generations.

At a meeting with a few Indians shortly after A.I 's death. General 'Smuts said:

"I welcome this conference. This is our round table conference so we can talk to each other as fellow citizens and I only regret as you do most deeply the absence of a very remarkable man whom I have looked to in years gone by for advice in the difficult problems that faced us. In A. I. Kajee we have lost a wise and very remarkÂable man, who as a businessman could give and take and who was not influenced by any particular ideologies but by facts. The late Mr. Kajee was a very good man to talk things over with, not only to you but to the GovernÂment and myself as Prime Minister."