Published date

Related Collections from the Archive

From the book: All That Glitters by Emilia Potenza

An industrial revolution was affecting the lives of everybody living in Southern Africa. By the 1920s, one or more members of nearly every family spent some time every year working as wage labourers on white-owned farms, on the mines or doing some other form of work in the towns.

Behind the scenes of the world of the workers

1904:The government under Lord Milner imposed rents on those who live on the crown lands. This was land owned by the government. It was a bit like the common land in Britain. It was often in the least attractive areas of the northern and eastern parts of the country.

1905:East Coast fever* spread amongst cattle throughout the country. Amongst the Pedi, for example, over 10 700 cattle were shot by officials. In the end, losses added up to 20 000 head of cattle, close to three quarters of their entire herd.

1910:Afrikaner parties had won elections in 1907 to have self-governing parliaments in the previous republics (the Transvaal and the Orange Free State). These governments came together with those of Natal and the Cap to form the Union of South Africa.

1913:The Land Act was passed. This law said that most of South Africa was white land and that African people could only own land in the reserves. The reserves now made up about 7,5% of the country. (The 1913 Land Act is dealt with in more detail later in this unit.)

1914-1918:During World War I, 146 000 whites, 83 000 Africans and 2 000 coloured men volunteered for service. When a troopship, the Mendi, collided with another ship in the English Channel and sank, 615 Africans on board died.

1924 -1929:A very severe drought occurred in many parts of the country.

Before the 1913 Land Act

Because most African kingdoms had lost their independence by the late 80s, African families had to set up new arrangements that enabled them to use the land. Some were able to occupy and farm the crown lands. After 1904 these families were obliged by law to pay rent to Milner's government.

The reserves, were areas of the country allocated for Africans to farm. It is impossible to estimate what percentage of the land was 'reserved' before 1913 because the concept of private ownership of land didn't exist among African communities. The land was considered to be a natural resource like the rain. Everyone had the right to use it and nobody could own it. So, an African farmer and a white farmer sharing the same land are likely to have had conflicting views about who 'owned' it.

In order to see how Africans lost the final traces of their independence, it is necessary to understand how they lost use of the land.

Changing relationships with the land

In the early 1900s more and more was being sold by the government to white farmers, mining companies and land companies. Africans who wanted to escape the crowded conditions of the reserves or the demands of the chiefs had to enter into some form of agreement with these new landowners:

- African families could become rent tenants on land owned by land companies or on Boer farms. This meant that they paid rent to the landowner in cash. (Nearly 20% of the farms in the Transvaal were owned by companies in 1905.) Rent tenants then had the right to live on the farm and cultivate some of the land. They could make extra money by selling the surplus that they produced. Often the landowner didn't live on the farm.

- African families could become labour tenants. This was the most common arrangement. It involved working for the landlord, usually for three to six months, in exchange for a place to stay and a piece of land to farm. In theory, African families could then farm for themselves for the rest of the time.

- African families could become sharecroppers. Sharecroppers owned family labour, ploughs, oxen and wagons that they could use to cultivate the land. They lived and worked on white-owned farms. In exchange, they 'shared their crop' with their landlords, i.e. they were expected to hand over between half to three quarters of what they produced.

- African men could become migrant labourers or wage labourers on farms. They could sell their labour to white farmers in exchange for very low wages. These labourers mostly did not live on white farms; they lived elsewhere with their families. On the whole, however, African farmers resisted wage labour at this time saying, 'We do not want wages, we want ground'.

Resentment grows amongst whites on the land

Boer farmers were mainly cattle farmers. They weren't used to cultivating the soil on a large scale. They were also often very poor and lacked the equipment and the labour they needed to use their land effectively. Although white farmers 'owned' the land, African farmers had the skills, the labour and often the equipment needed to farm the land.

White farmers could not compete with the mines in getting labourers because they paid less than the mines did. They started to feel resentful about their dependence on African tenants and sharecroppers. They accused rent tenants of being stock thieves. They began to demand that the government control the conditions under which Africans could remain on white farms.

There were also whites who had no land of their own. They had to compete on the land with African tenants and wage labourers. They were often at a disadvantage because they were not willing to make use of family labour. Those who failed to make it on the land were forced to migrate to the towns. Many blamed African farmers for their misfortune.

White farmers won the sympathy of church leaders and politicians. In response the government passed the 1913 Land Act.

The 1913 Land Act

The only areas where it was legal for Africans own or lease land were the reserves. The 1913 Land Act officially limited the reserves to about 7,5% of the country. Africans who ready owned land outside the reserves could keep this land, but could not buy any more.

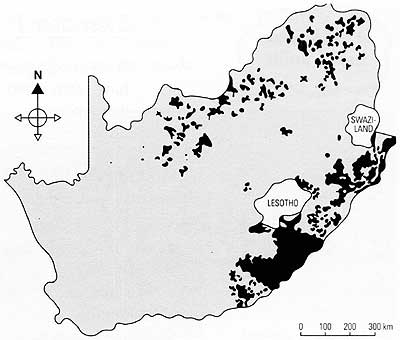

The Land Act "reserved" 7.5% of the country for African ownership

The Land Act "reserved" 7.5% of the country for African ownership

Taking away the right to own land from the majority of people in the country gave the government, the mine owners and white farmers a great deal more power. The main purpose of the Act was not to keep Africans off white-owned farms; it was in fact to control the conditions under which Africans could remain on white-owned farms.

An important aspect of the Act was that it made rent tenancy and sharecropping illegal. Because it was left to provincial authorities to implement this part of the Act, it took a long time for these changes to reach certain parts of the country. Nevertheless, over time many rent tenants and sharecroppers were forced to become labour tenants or wage labourers. This often caused tensions between fathers and their sons. It was common for African youths to refuse to become labourers on white farms; they preferred to leave the farms and seek their fortune on the mines.

There were also many cases where African families were evicted by farmers who were afraid of being fined under the Act. This led to dramatic 'forced removals' which left many homeless, especially in the Orange Free State where there were no reserves.

The quote below describes the horror of a family in the Orange Free State in 1913 after they had been evicted from a farm. As they were 'trekking' rough the countryside in the bitter winter cold, one of their children died of exposure.

The deceased child had to be buried, but where, when and how?”¦even criminals dropping straight from the gallows have an undisputed claim to six feet of ground on which to rest their criminal remains, but under the cruel operation of the Land Act little children, whose only crime is that God did not make them white, are sometimes denied that right in their ancestral home.

From Native Life in South Africa by Sol T. Plaatjie, 1916.

The 1913 Land Act took away from Africans the last traces of their independence. Except for the few who were able to survive in the reserves, most Africans would in time be forced to become wage labourers on white-owned farms, on the mines and later in factories.

The hungry mines

For many young men the Land Act meant finding work on the mines. These men ended up working mainly on the diamond mines in Kimberley and gold mines on the Witwatersrand, but also in the coal, platinum, tin and asbestos mines in the Northern and Eastern Transvaal.

Soon laws were introduced which favoured the mine owners. Migrants had to sign contracts, which prevent them from leaving a mine if they were unhappy with the wages or conditions of service. Controls were introduced over drinking and deserting. Migrant labour, once a weapon in the hands of the workers, which they could use to their own advantage, now became a form of control.

Because the mines were so hungry for labour, at various times foreign workers were also recruited. Migrants came from countries like Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Botswana, Namibia and Angola to work in the gold mines of South Africa.

StimeIa (the coal train)

Many songs, novels and poems have been written about migrants on their way to the mines.

The men are going ... the women are staying

While African men and older boys went to work on the mines, the women and children, as well as the elders, remained in the rural areas. Chiefs and elders were strongly opposed to women going to the towns.

Most men who came to the mines in these early days until about 1930 maintained contact with their rural homesteads. If they were unable to return home on a regular basis themselves, they would be sure to send money to their families.

A thousand ways to die

Safety is a very important issue in the mines. Workers are constantly faced with unexpected situations underground. Aside from accidents caused by mistakes, mineworkers have to deal with things like rockfalls, which are difficult to predict.

Since the turn of the century, 69 000 miners have died and more than a million have been seriously injured. At present levels, an underground miner who spends 20 years working underground faces a 1 in 30 chance of being killed and a risk of nearly 1 in 2 of being permanently disabled.

In May 1995 there was a terrible disaster on Vaal Reefs gold mine near Orkney. A locomotive fell down a shaft and landed on a lift cage that was transporting workers - 104 men were killed.

At least one life has been claimed for every kilogram of gold that has been produced in the past century?