Archive category

Publication date

Published date

Download the file

Related Collections from the Archive

Petrus Mashishi, President of the South African Municipal Workers Union (SAMWU) from its founding in 1987 until 2009, was both a man of his times and a giant representing working class principles of co-operation, democracy, probity and the best in human values. He lived through the rigours of apartheid, the transition to democracy, and in more recent times the splitting of the trade union movement he had helped to found. He was witness to the rise of predatory and corrupt tendencies within the state, out of what had once been a proud struggle for liberation.

May his passing on the 3rd July 2018 be marked as a moment of contemplation in which divisive voices within the ranks of the trade union movement are stilled. What he stood for was the antithesis of what he had to witness in his own union and in Cosatu over the past 8 years. He witnessed it at its sharpest when with Charles Nupen he was asked to mediate differences within Cosatu and failed. He witnessed SAMWU splintering as one group expelled any leader of principle who demanded financial accountability. He witnessed the looting of union finances.

Yet to the end Mashishi hoped and believed that worker unity could be forged anew.

Petrus Mashishi was born on the 28th June 1948 in Alexandra. After leaving school he was taken on by Johannesburg City Council in 1969 to be trained as an artisan in terms of the Bantu Building Workers Act of 1951. This Act provided for the training of African building artisans on condition that they only be allowed to work in black residential or bantustan areas. His specialisation was in plumbing and sheet metal working. In the early 1970s the Apartheid state established Bantu Administration Boards in urban areas to remove black townships from ‘liberal’ white municipal control. Petrus and his fellow artisans found their jobs under threat as the registered white and coloured unions questioned their continued employment in white and coloured areas.

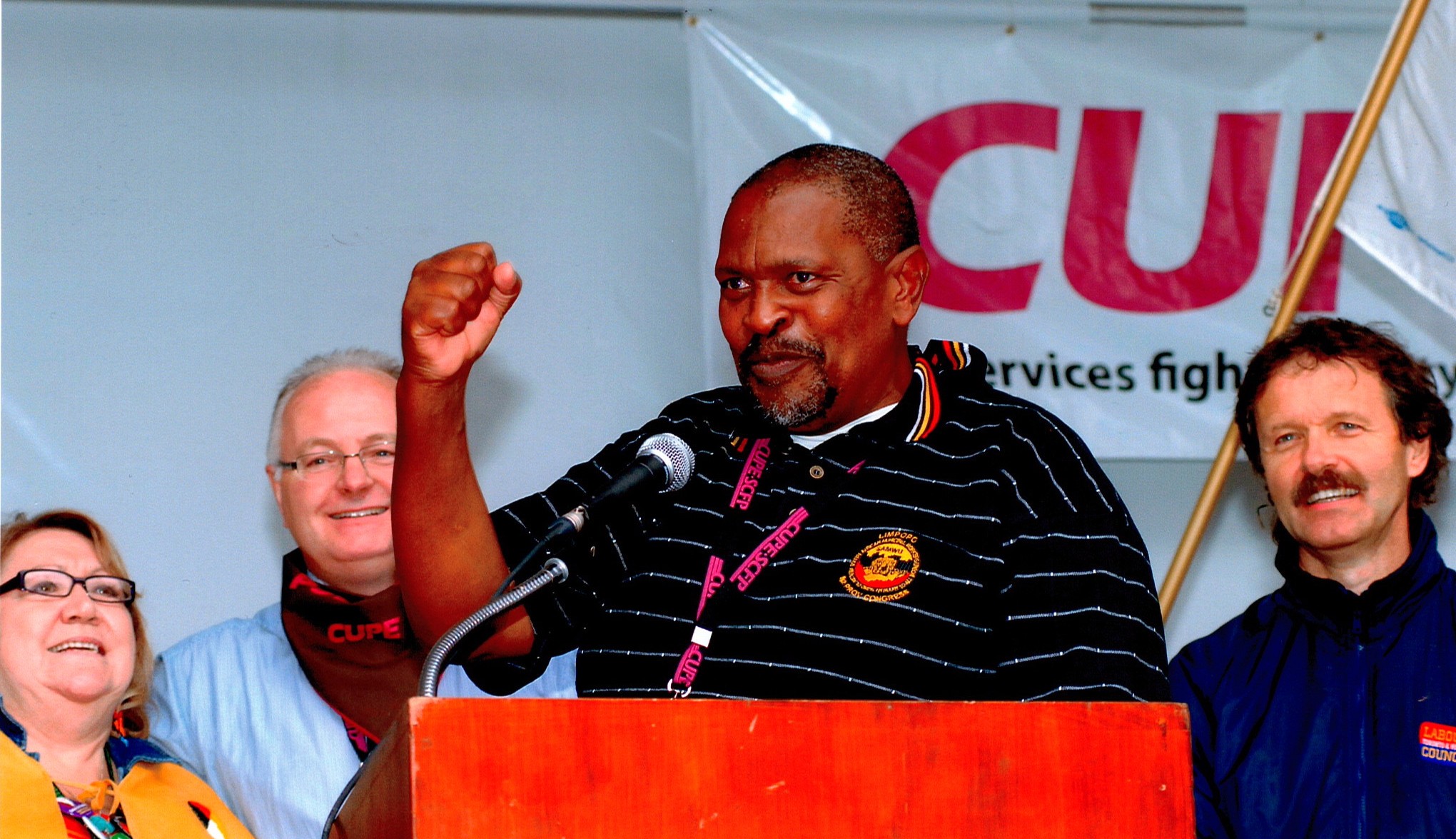

Mashishi at a rally of the CUPE in Canada

Mashishi at a rally of the CUPE in Canada

Comrade Mashishi and a group of affected workers approach the Industrial Aid Society (IAS) in 1978. IAS was an advice centre associated with the Trade Union Advisory and Co-ordinating Council (TUACC). TUACC had emerged from the 1973 strikes in Durban. It had recently become a national federation with its roots in Natal and the Witwatersrand. These municipal workers become members of a structure called TUACC Workers Project. A press campaign and pressure from bodies such as the Black Sash and Council of Churches forced the City of Johannesburg to keep them on. He also participated in educational classes run by sympathetic Wits University intellectuals, such as the late historian Phil Bonner, around issues of South African working- class history and organisation, labour internationalism and basic labour law. Petrus was an avid reader, self- educator, and educator of fellow workers. An organic intellectual of the working class.

In 1979 TUACC gave way to the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu). Municipal workers were to be organised by the Transport and General Workers Union (T&GWU). Comrade Mashishi became the Transvaal Branch Chairperson and also a member of the union’s NEC. It was under Fosatu that he developed, and himself fostered, the key principles of workers controlling the union through participatory democracy. He was also exposed to issues of gender equality. He promoted a strong sense of union independence from employers and from political parties. Worker politics meant above all fostering workers unity. Party ideologies and interests were important, social and economic policy development was crucial, but workers needed to formulate their own union positions through internal debate and compromise. This central emphasis on workers control was about control over the union, its officials and leaders, but it was also about extending workers control over the shop-floor and society. Petrus stood for workers democracy and Socialism.

Organising of T&GWU in Johannesburg was difficult. The union used Works Committees as a tool to organise around and make representations. In the Depots it was strong in that it opposed the establishment of Liaison Committees. In 1980 the City Council HR Department sought to turn its coordination liaison committee structures into a sweetheart union to which all African workers would be forced to belong through a closed shop. Led by the bus drivers’ leader the late Joe Mave and by the late Martin Sere in the electricity department, and Phillip Dlamini, there was a walk-out. It was decided to set up a Black Municipal Workers Union (BMWU). They had hardly started organising when workers exploded in a mass strike. The T&GWU members joined the strike. There were mass dismissals with many in the dominantly migrant workforce being forcibly bussed back to the bantustans.

1993 March against hostel violence

1993 March against hostel violence

BMWU was soon affected by splits. This was over the use of relief funds and ANC versus PAC politics. This led to the formation of the General Workers Union (MGWUSA) which aligned with the UDF and the SABMWU led by Dlamini and espousing PAC affinities. T&GWU stayed its course. In the aftermath it expanded its membership considerably by negotiating re-employment of many workers.

Comrade Mashishi served on the T&GWU Transvaal BEC and NEC in the early 1980’s. He served as a T&GWU representative in the “unity talks” to create a national municipal union. This process had its conflicts and delays, starting early in 1986 and dragging on to the launch of SAMWU in October 1987. The key unions in these talks were the Cape Town Municipal Workers Union (CTMWA), the T&GWU municipal sector, which were seen as ‘workerist” and a number of unions affiliated with the United Democratic Front (UDF) and characterised as “populist” in the rhetoric of the time. The latter included Municipal Workers Union of South Africa (MWUSA), a merger of MGWUSA from Johannesburg and a small Natal union, the South African Allied Workers Union (SAAWU) members from East London municipality and members of the General Worker Union of South Africa (GWUSA) from Port Elizabeth. Despite their differences SAMWU was finally launched.

CTMWA had looked to T&GWU to put up a person for President or Vice President while their John Ernstzen became General Secretary. The T&GWU caucus chose Mashishi to stand for President and Joe Spambo (Molitsane) from Natal in case other positions might need to be contested. Typically, Petrus was reluctant but the caucus was unanimous. The intention was that one from the other “UDF” unions would be elected as Vice President. However, their nominee was unacceptable, having antagonised many. In the end both Petrus and Spambo became President and Vice President.

There was a union on paper, but structures still had to be built from the bottom up. T&GWU, CTMWA and SAAWU had shop steward committees and membership. There were doubts about MWUSA’s democratic and membership substance in Johannesburg although the Natal section was strong in Newcastle. MWUSA as a municipal only union had formally to dissolve itself. CTMWA’s registration was to be the shell to register SAMWU by name change. T&GWU municipal members and the other workers were transferred from unions which remained in existence. In the end in the early 1990s four organisers for this stream were dismissed by the union for divisive activity which also included misleading workers in a number of smaller municipalities, later to form part of Ekhuruleni, about the dispute they claimed SAMWU had failed to support. In fact, the employers had declared the dispute. In the course of this division Petrus and a fellow leader were held hostage by angry workers in a hostel for 5 hours. They finally persuaded workers of their credibility. The union including MWUSA members who had invaded an NEC meeting on behalf of the dismissed officials emerged more united than ever. Comrade Mashishi was no stranger to the difficulties of countering divisive behaviour.

It was a hallmark of the comrade’s approach to trade unionism throughout, to turn the attention of the union to its grassroots. In these first years while the union was to be the most rapidly expanding union in South Africa it was hard work keeping up with all the problems. The union grew from perhaps 12 000 members at its launch to over 80 000 by 1993 and 120 000 by 1996. This was through recruitment, but also through merger of other pre-existing municipal in-house unions. The most substantial being the Durban Independent (previously Indian) Workers Union. Mashishi was a central figure in recruiting and negotiating municipal worker unity. This included uniting with the coloured municipal union in Johannesburg and a dummy union from 1980. SAMWU had by then expanded considerably in Johannesburg. A key moment that convinced workers of their home was the unions agitation and march in 1993 against hostel violence by Inkatha.

In all of his 22 years as SAMWU President he also represented SAMWU in COSATU and gained widespread recognition for his articulation of worker democracy and unity. It was fitting that Mashishi was to be one of the worker representatives sent by Cosatu to participate in the Cosatu September Commission in 1997 which sought to address the emerging problems of union organisation in a new democratic order. He also served Cosatu in a variety of capacities and was one of the longest serving member on its CEC by 2009. He also represented the Federation on the Labour Development Trust Board.

He was a key figure in Local Government Bargaining and the establishment of the South African Local Government Bargaining Council (SALGBC) in 1997. He occupied positions on the Executive and Negotiating Committees of the SALGBC through tough negotiations and strike actions in 2002, 2005 and 2009. He led the union from a point where it consisted of scattered groups of organised and semi-organised workers to a national union which could pull off repeated strike action across the country. He was a clear- headed strategist and effective negotiator. He was respected by the other major union in the sector, IMATU, as by his opponents in the South African Local Government Association (SALGA).

From 1996 onwards when Government shifted its economic policy to GEAR, which included privatisation. SAMWU was to be at the forefront in resisting privatization. In 2002 it faced a critical challenge with Johannesburg’s iGoli Plan. The struggle was lost in the short term. The mess that Pickitup and City Power have represented since then show us the consequences. This process was accompanied by a shift to casualisation, sub-contracting and labour broking. This fragmentation also affected union democracy and Mashishi, with his fellow office bearers, such as the late Boss Nxu and General Secretary Roger Ronnie were at the forefront in urging new strategies to organise these new workplaces and to find ways of representing them in union structures.

Mashishi represented the union at a number of Public Service International (PSI) Conferences and gained much respect from fellow unions globally for his clear respect and concern that union should serve their members interest and be directed by workers. His also provided direct support to Mozambique comrades.

Mashishi was part of a struggle for worker unity. A struggle to advance the rights of workers to justice and equality. He was never alone, because he inspired respect, and led from the front, yet remained always humble and a man who listened carefully, taking his counsel from grassroots workers. Mashishi always ensured that he remained active as a shop stewards and faced regular re-election processes in his workplace-constituency and serviced his electorate. Not for him the perks of office, not for him upward mobility out of the working class.

Long live the spirit of Petrus Mashishi – long live.

______________________________________________________________________________

Based on interviews by John Mawbey, ex- SAMWU official, and previously a T&GWU official with Petrus Mashishi in 1998 and by Melanie Samson in August 2003.

_________________________________________________________________________

A Union for Angels

(In loving memory of Comrade Petrus Mashishi)

He was larger than life

Starting as a municipal plumbers assistant

As grudgingly allowed

By apartheids hideous demarcations

Did all the work

While supervised by one

Who couldn’t do anything

Without him

He held no malice

Said he actually

Felt sorry for them

For deep down inside

They knew they were lost

And their time was coming to a close

Soaked up the unfolding situation

Like a sponge

Understood early

Workers had the power

If they organized

If they were clear

If they were encouraged

Given confidence

Class confidence

Laughed often

Especially at the stupidity

Of the system

It was murderous

But he simply refused to be intimidated

Became an organiser

Helped build a formidable union

Was elected a leader

Dedicated his life

Never stole a cent

Never ignored a mandate

Always reported back

Built a team

Spoke truth to power

Often

Made mistakes certainly

But learnt from them

Was not afraid to apologise

Reminded his own comrades

What the struggle was about

Refused to let them forget

Some were grateful

Others resentful

Didn’t go to Parliament

Happy where I am he said

With the workers

Woe betide those who sell us out

Whoever they might be

Happiest?

Seeing workers educated

And being at home with loved ones

Experienced tragedy

A son lost to a motor accident

Much more besides

Held Ma Judith, Koto and Tshepo close

Stayed philosophical

Practical

Ready to share his woes

But only if asked

Never touched alcohol

Or tea or coffee

I learnt to bring hot water or juice

First one there in a morning

Ploughing through the papers

Then documents

Then a list of jobs for the day

Like an artisan

Fixing a leaky movement.

Could laugh like a drain

Liked being teased

Adored Chinese food

And took us for lunch

The proprietor

Knew his favourite dishes

I sometimes wonder

Did we deserve him?

Those who fed on factionalism

Stood around in their own luke warm piss

Like a pipe-fitters nightmare

Waited for their opportunity

It came at the Bela Bela Congress

He never lobbied

Some urged him to stand again for election

Then left him stranded and exposed

While empty headed nondescripts

Dreamed of new cars

I wept

I wasn’t alone

But we were noted

Regarded as disloyal thereafter

By those so-called modernists

Whose avarice was as old as time

They took their cue

Not from principles

But from the new millionaires

Inside and outside of government

Their grubby hands eager

To maul workers money

And maul those who tried to stop them

It did not take them long to pillage and loot

To unravel the safeguards

And lie through their teeth

And those with vested interests let them

And we let them

Our loyalty to the Union exploited

By those loyal only to themselves

And a once mighty union now clings

To a coat hanger

They turned their backs on him

And all he stood for

But they will no doubt try

To claim him as theirs

The schemers, the thieves, the misleaders

But they will fail

And miserably so

The unavoidable stark contrast

Between their actions

And his work

Will haunt them into perpetual shame

Well be ashamed!

You lightweight imposters

You who dare not face your own members!

Your time will come

As certain as day follows night

In retirement he worked just as hard

Towards the end

His beloved wife took away his phone

The only way to make him rest

And now he rests forever

On my first day he said

Let’s take a walk through the City

But we could not go more than 20 metres at a time

Before someone called him with an Amandla!

Or stopped to update on a grievance

Or asked about the wage claim

Or what he thought about the latest crisis

Or just for the joy of vigorously shaking his hand

In anticipation of his laughter

Rumbling and rolling up from deep inside

Informal traders knew him by name

Bon jour Monsieur Petrus ca va?

Oui bien merci! He replied

Laughing and waving at the same time

He organized them too!

I laughed again

When three buses

Stopped side by side

In formation

Blocking the main road

To let us amble across

Each driver calling out in turn

Howzit Prez!

What’s happening Mashish?

Need a ride Com?

When I asked

Is it always like this?

He replied

Out here

Each one teaches one

Then he noted a paving stone

That I had tripped over

Must get that fixed he said

Two days later

It was

There will be no shrines for Petrus

No posthumous awards

He refused his name on a Union building

But he will never ever be forgotten

On the day he died

His sister said

He will be organizing in heaven now

Imagine

A union for angels

Lead by a humble plumber.

sf0718

- Interviews with Petrus Mashishi by John Mawbey, ex- SAMWU official, and previously a T&GWU official in 1998 and by Melanie Samson in August 2003.

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1EL1DulmhgUSdIRurmq3zbvxgGMrOMrgK5k19WHSCtZk/edit?usp=sharing Speech by Petrus Mashishi 2009

- https://www.cosatu.org.za/show.php?ID=14055 Statement by Cosatu

- https://karibu.org.za/the-working-class-above-all-else/ Tribute by Khanya College

- https://saftu.org.za/saftu-statement-on-the-passing-of-founding-president-of-samwu-petrus-mashishi/ Tribute by Saftu

- https://www.samwu.org.za/press-statements/item/1558-samwu-morns-it-s-founding-president.html Statement by Samwu