Key Words: Can Themba, Apartheid, Writer in Exile, Drum Magazine

Born: 1924 Marabastad, Pretoria

Died: 1968 Swaziland

Education: High School, Polokwane

University of Fort Hare:English Degree

Rhodes University: Teaching Diploma

Work: Teacher- Madibane High School

Johannesburg Indian School

St. Joseph’s Missionary, Swaziland

Journalist and Editor- Drum Magazine

Can Themba. Photograph by Drum Photographer. Permission: Baileys History Archives

Can Themba. Photograph by Drum Photographer. Permission: Baileys History Archives

Golden City Post

Can Themba was born a Black South African in a country where his race comprised of the majority. His status in the population did not reflect the living style that would commonly be associated with someone who would be living in the land of his ancestors. Instead, Themba was constantly on the receiving end of the prejudices, hostility, and control the White people of South Africa directed towards the Blacks in that country. He did not remain silent, though. Themba educated the next generation of his people as a means of defying the inferiority that the White people were insisting to define the Black people by. He also wrote about the brutalities of the apartheid regime in various South African newspapers. The world that surrounded him did not get better in his lifetime, though. As the struggle between Blacks and Whites continued, Themba and many of his companions turned to alcoholism and a party life to cope with the bigoted intolerance they had to face amidst their race’s fight for freedom. It was not long before the consequences of this lifestyle caught up to Themba, and he felt it was best to leave the country. Swaziland became Themba’s temporary home and, not long after, his permanent one as well when he died there at the age of 44. At the end, Themba lived up to the maxim that him and his peer writers of apartheid South Africa had for living in the days of apartheid South Africa: ‘Live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse.’

Introduction

Writers are often considered the minority in many societies. Many begin dozens of stories, but only a handful are able to spin these beginnings all the way through into substantial endings. These few can be considered as the compendium of our society. They are forced to live as a member of the society once, and then again when they sit at their desks and craft up their lives into words. Each community has their own group of these individuals. In America there is Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In England, there is Jane Austen and Charles Dicken. In Russia there is Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. And, south to all these countries, there are the writers of South Africa. These individuals include Can Themba, Miriam Tlali, Nat Nkasa, Nadine Gordimer, etc.; they have been able to use ink and paper to bring to life the story of South Africa. Can Themba, particularly, has been the embodiment of the Black African Struggle during apartheid in South Africa, and his literary works made him even more attuned to and personally susceptible to the tragic situations of his people.

Birth of a Writer

Can Themba. D’Orsay Can Themba. Can Von Themba was born in 1924[i] in Marabastad, Pretoria[ii] . His surname has Shangaan origins.[iii][iv] He was born one of four children where financial challenges plagued a family disadvantaged by racial discrimination in a country under white minority rule.[v] Despite this, Themba was able to get an education. He went to high school in Polokwane, and was the first to get the Mendi Memorial Scholarship to the University of Fort Hare.[vi][vii] In 1947, at the age of 23, he graduated with an English Degree.[viii] It was in the University of Fort Hare where Themba began his literary career. His first short story appeared in a publication of the University, The Fort Harian, and his poems in Zonk, a magazine in South Africa.[ix] Close to a decade after his graduation from Fort Hare, Themba won a short story competition hosted by Drum with his work, Mob Passion. Themba was deeply inspired by this, and he said, “I feel inspired to go on writing and writing, until one day, perhaps, I’ll be a really famous author”[x]

Living in apartheid South Africa

“Nude Pass Parade”, written by Can Themba appearing in Drum Magazine, 1957. Photograph by Peter Magubane. Permission: Baileys African History Archive

“Nude Pass Parade”, written by Can Themba appearing in Drum Magazine, 1957. Photograph by Peter Magubane. Permission: Baileys African History Archive

Themba's life was shaped by the legislation of segregation and apartheid in South Africa. His attempts to deal with the indignities of apartheid are revealed in some of his works. He despaired the inhumanity of pass laws[xi][xii] , as evidenced in one of his journalistic writings Nude Pass Parade. He described a human being going through this process as feeling ‘Naked. Humiliated. Hoping to God time’s going to go quickly’.[xiii]

The concept of apartheid in South Africa was implemented by the National Party, a political party that had risen to power as a result of increasing Afrikaner nationalism. This party enforced laws and acts onto the Black people who were already living in South Africa in order to take control of a population that struck them as different due to their skin colour. Consequently, the people who were subjected to these laws, including Themba and his people, found their lives to be in a state of almost constant uprooting due to the actions of the National Party.

Leaving Sophiatown

In addition to the Pass Laws, Themba, along with thousands of other Black South Africans, suddenly learnt that they were going to be deprived of their homes in the 1950 Group Areas Act. This act relocated all non-White Africans to segregated townships further away from city centres. Prior to this, most Blacks were not allowed to own land in the White cities, so there were some freeholds put aside where they could live in their own places. These places developed into rich and diverse Black communities despite the limits in their land area and the unbelievably large population. One of these towns was Sophiatown. A hub of music and culture, it was a haven for the Black South Africans, including Themba. Many of his works are based on this place and the lived of the people there, including The Suit. Some understanding of how Themba was seen by the people of Sophiatown can be gained from Stan Motjuwadi, a student of Themba’s. Motjuwadi describes him as a ‘swarming, cacophonous, strutting, brawling, vibrating life’.[xiv] He also mentions going to The House of Truth[xv] , which was what Themba called his place in Sophiatown after converting it into some sort of shebeen.[xvi] As its name denotes, the House of Truth was literally a place of truth as declared by its owner. It was a sort of intellectual platform for many Black South Africans who associate Themba with it. After Sophiatown’s destruction, Themba talked about the beauty of Sophiatown and his longing desire to go back to his life there in Requiem for Sophiatown. He describes his favourite shebeen[xvii] , Fatty of the Thirty-nine Steps on Good Street, when it was torn down, ‘where it should have been was a grotesque, grinning structure of torn red brick that made it look like the face of a mauled boxer trying to be sporting after his fight. A nausea of despair rose up in me, but it was Bob his friend who said the only appropriate thing: “Shucks”’.[xviii] This and many other places were what had helped the Black people cope with everyday life in apartheid South Africa, and were destroyed under one swift act.

Struggles as a Teacher

A few years after the Group Areas Act, another Act was passed that affected Themba greatly since his profession as a Teacher was heavily defined by it, The 1953 Bantu Education Act.[xix] The passing of this established an inferior system of education for Black students that would grow them to be educated enough to work but nothing more.[xx] Since Themba was educated prior to this, he was not forced to undergo this new system of education. He had become familiar with the works of Shakespeare, Milton,[xxi] Euripedes and Blake[xxii] , and it only made sense that he wished to part this knowledge onto the next generation. He was able to do this as a teacher at Madibane High School and Johannesburg Indian High School after receiving a teaching diploma from Rhodes University.[xxiii] Motjuwadi, a student at Madibane High School, said that Themba left him and his peers awestruck by the amount of knowledge Themba possessed on literature. He continues, “From the moment he opened his Themba mouth to address us, we were, to use a cliché, eating out of his bony palm.”[xxiv] Yet, when the 1953 act was passed, Themba was forced to downplay the education that he had received during his school years and convey a much more watered down version of it to his students. He was deeply annoyed at this as this incident contributed to how insignificant his race was forced to become in their land. The Suit, one of his works, features a character, who joins a group of women protesting this act.

Coping with the Prejudiced Lifestyle

These kinds of discrimination and dehumanization affected the spirit of Themba. Lewis Nkosi, as friend and worker of Themba’s was able to comprehend Themba on a familiar level that only comes from acquaintanceship and empathy. Nkosi describes how Themba sought to live under apartheid: in his own way Themba tried to reduce the South African problem into some form of manageable game one plays constantly with authority without winning, but without losing either.[xxv] Besides the Afrikaner’s belief of the inferiority of the Black man according to skin colour, there was another motivating factor for their discriminating behaviour towards the Black people. The former feared the latter. The Afrikaner’s were on foreign soil that was native to the Black people. For them, any accomplished Black South African was a source of fear because of their automatic belief that that person would get beyond their control. This put many Black South Africans in quite a predicament. Nkosi describes Themba’s struggle with this situation. ‘ Themba was forced to look “dumb” in order to reassure very dumb white citizens whose sense of security was threatened by any “native” who seemed imaginative enough and talented enough’.[xxvi]

Can Themba (left) with his friend and two beauty queens of his time, 1958. Photographed by Drum Photograph. Permission: Baileys African History Archives

Can Themba (left) with his friend and two beauty queens of his time, 1958. Photographed by Drum Photograph. Permission: Baileys African History Archives

As these frustrations and indignities affected Themba’s life for the worse, he turned to drinking and other outlets to deal with his cooped up anger at the prejudices that his people had to face with. Mike Nicol, a Cape-Town author and journalist, writes that ‘he Themba wallowed in township life: the shebeens, the shebeen queens, the good-time girls, the singers, the gangsters’.[xxvii] He was especially known for his drinking among all of his friends and colleagues. It was a rare day that passed with Themba being sober throughout it. His lifestyle and the number of girls he encountered gave him a fair share of affairs. The most prominent of these was with a white woman named Jean Hart who was already married. Their affair did not start much after her arrival in South Africa in 1957.[xxviii] Hart says, about Themba, that ‘he turned out to be a most gentle and tolerant and humane person…’.[xxix] She also mentions that there were times when Themba would withdraw from her due to the impossibility of a happy outcome from their affair. Hart was one of the few women perspectives given into Themba’s life. As a mistress of his, she knew Themba intimately. She says that Themba did live his life with rash moments. However, he was never able to leave his analytical side behind in these moments, and he was constantly reminded of the reality of the apartheid world he lived in; he could never really escape it unlike many of his companions on their escapades. [xxx] Not long after the affair had begun, they were discovered, and Jean was forced to leave South Africa while Themba remained trapped behind the bars of apartheid.

Marriage

Themba did eventually settle down. His wife was Mrs. Anne Themba.[xxxi] They had two daughters: Yvonne and Morongwa.[xxxii] Anne Themba survived her husband by close to half a decade, but there is no other significant information given about Themba’s marital life.

A ‘Drum Boy’ and his Writings

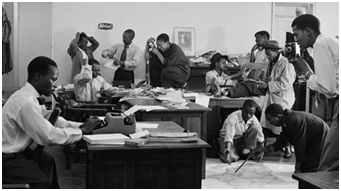

Themba (standing to the right of the ‘Africa’ sign) in the Drum office with other Drum writers. 1954. Photographed by Jürgen Schadeberg Permission: Jürgen Schadeberg

Themba (standing to the right of the ‘Africa’ sign) in the Drum office with other Drum writers. 1954. Photographed by Jürgen Schadeberg Permission: Jürgen Schadeberg

Themba was living another life parallel to this reckless and amorous one as a member of a group who called themselves the ‘Drum boys’[xxxiii] . It must be noted that he was also a writer, and later editor, at another media sister of Drum, Golden City Post, but his time there was overshadowed by his life at Drum[xxxiv] . His aforementioned lifestyle remained a huge obstacle to his success as a journalist, though. Many said that he had talents that no other writer had; that he had the education; that he had the standpoint to write the truth because of his position as a Black person under a White apartheid government, yet he also squandered these abilities while drowning himself in alcohol. Obed Musi, a journalist of Drum, though, talks about Themba’s inability to truly get into journalism: ‘Can was more of a teacher than a journalist, more of an intellectual than a hard scribe, more of a pedagogue…’.[xxxv][xxxvi] Nevertheless, the truth still remains that Themba the journalist remained an enigma to many of his peers.

There are other more modern day critics who criticize Themba and his colleagues as being romantics. For them, these writers were no more than people aspiring to have what they could not: the life of a White South African. Michael Chapman, who specializes in South African literature, said that these critics considered the writers to be bitter. They claimed, ‘writers like Themba sought personal transfigurations of social experience because they reveal the false consciousness of their petty-bourgeois aspiration’.[xxxvii][xxxviii] That is, the writings were corrupted and made overtly emotional by the aspirations of of its authors.

Themba being sent out of a Seventh Day Adventist Church after trying different White Churches to see which one would let him stay. Permission: Jürgen Schadeberg

Themba being sent out of a Seventh Day Adventist Church after trying different White Churches to see which one would let him stay. Permission: Jürgen Schadeberg

Chapman, though, attributed this to the fact that Themba was writing fiction and therefore had to have emotion, or else it would lose the entertainment and attention aspect of such writings.[xxxix] Without emotion, Themba’s fictional stories would probably not have communicated with the large black populace and incite in them the fire for the justice he believed they deserved. His level of melodrama was only to be expected. The moments where his works did seem more love story than a representation of black life can be justified by the formidable challenge Themba may have faced in keeping his stories entertaining and, at the same time, a depiction of his people’s terrible conditions.

Though Themba was most famous for his stories, they were not all he wrote. He also did articles on the injustices being done in South Africa. He would write about ‘gangster terror[xl] , illegal brews that were killing the unwary in the cut-throat shebeens,’ Nicol says, and continues, ‘he was the grim witness of Sophia town’s destruction’.[xli] These works of Themba’s, being on a more serious end, played a role in preventing him from escaping the prejudices towards the Black people that were surrounding him. Consequently, it may have played a role in his continued decline into alcoholism as well.

As Themba drifted deeper into the careless routine of recklessness that he had built himself, his career started to down spiral as well. Tom Hopkinson, the assistant editor of Drum at the time and Themba’s supervisor, understood that drinking was the form of defiance that Themba and his companions had taken up to represent their stance against apartheid, but he says, ‘to have them drunk and absent just when they were needed most ran absolutely against the grain’.[xlii] Themba had been promoted to associate editor by this point, but, in the late 50s to early 60s, he got fired. It was not much after this incident that he could no longer stand the way his life had become and the threat of living as a Black, especially a journalist, in South Africa. Consequently, he ran away to Swaziland in 1961.[xliii] But he was not just leaving behind his companions and life as he knew it behind, though.

Arriving in Swaziland

When Themba arrived in Swaziland after leaving South Africa, he arrived at the St. Joseph’s missionary, where a man named Father Ciccone was resident. In a Drum interview with Father Ciccone, Father Ciccone recounts the night he heard Themba knock on his door: ‘“when I opened the door there stood this dashing, handsome young man”. He continues, “The caller introduced himself as Can Themba, a journalist and writer escaping the unjust apartheid system in South Africa. Father Ciccone pauses before saying with deep admiration, “That was my first encounter with this great writer, friend and hero.”’[xliv] A friendship soon formed between the two individuals. Father Ciccone comments that Themba’s was a lonely life. He never had any friends or loved ones in Swaziland. Consequently, He soon relapsed into his old habit of drinking.[xlv] It was only his taking up of the teaching post in Swaziland that added a social aspect to his life.

Back to Teaching

Themba began teaching at the school in St. Joseph, where he lived, and it was here that he influenced the life of another great writer of Africa: Mbulelo Mzamane. In an appearance on the South African Broadcasting Digital News, Mzamane talks about how Themba taught him about literary giants, including Shakespeare.[xlvi] For Themba, this must have been a reprieve from the inferior education he was forced to teach the kids in South Africa due to the Bantu Education Act. This ability to do so did not cause Themba to forget South Africa’s struggles, though. He never really stopped being a voice against the apartheid in his homeland. His mere presence, when combined with his and Father Ciccone’s preaching, made sure that the true nature of the apartheid regime of South Africa did not remain an unknown topic in Swaziland for long.

Outlawed

Leaving South Africa at this time was not an uncommon path taken by many Black South Africans including many renown political figures that were on the forefront of the anti-apartheid government. These figures, like Themba, never stopped speaking out against apartheid no matter what corner of the globe they were at. This enraged the South African government. They would often send out search parties to bring these people back. Themba was no exception to this. Father Ciccone mentions the times when he had to hide Themba from the people the South African apartheid rule sent to find him. ‘The South African secret police were hellbent on making his stay here unbearable as they snooped around trying to catch him,’ Father Ciccone says.[xlvii] Whether due to their failure in catching Themba or not, in 1962, around a year after he had left the apartheid government, the apartheid regime declared him to be banned, along with all his works on the basis that they were communistic and promoted an unsupported form of governmental reform[xlviii] , from South Africa.[xlix] Not many works of Themba’s could necessarily be considered as revolutionary. Most of them gave facts and an emotional viewpoint into the lived of a Black South African. They were written to make people realize the tragedies; they did not necessarily dictate what approach should be taken to prevent these misfortunes. However, the apartheid regime claimed that they did. Two things came out of this. The first was that Themba’s voice was effectively subdued in South Africa. The second, though, was that it became a rallying force for all the people who wanted to fight against the conditions that Themba’s works portray. The White South African government had made a martyr out of Themba’s writings.

Death

It was not many years after this when Themba departed from this world. He is said to have been buried in the St. Joseph’s cemetery. A mystery shrouds his death, which occurred in 1968.[l] . As for the controversy, there are two main opinions. Nkosi wrote the following oblique statement: his heart just stopped in his obituary for Themba.[li] Nkosi and the others who accepted this verdict for Themba’s death were probably not surprised in light of his heavy alcoholism. Some others, though, have made his death into a source of conspiracy directed towards the apartheid government. Whichever the case was, the fact remains that Themba died far from his home on foreign soil in Manzini.

Legacy

As the initial struggle to end apartheid was coming to an end so did the ban on Themba’s voice in South Africa in 1982, fourteen years after his death.[lii] Around two decades after this, on September 27, 2006, Themba was awarded The Order of Ikhamanga[liii] in Silver for ‘excellent achievement in literature, contributing to the field of journalism and striving for a just and democratic society in South Africa’ from the president of South Africa at that time.’[liv] During the time that he was alive, Themba had also received another award: Henry Nxumalo[lv] Award for journalism from the Writer’s Association of South Africa.[lvi] The struggle still goes on to fix all the broken pieces of Themba’s land that was once so peaceful. However, as the process continues, the world must not forget the men like Can Themba. The men who lived and died fighting this battle without ever getting to witness the light at the end of the tunnel.

Primary

Gordimer, Nadine. "Can Themba." Speech, Can Themba Memorial Lecture, State Theatre,

Tshwane, Gauteng Province, South Africa, October 18, 2016. Available at http://artsnash.com

Stan, Motjuwadi. "The Man from The House of Truth". The World of Can Themba. Can Themba. 1st ed. Braamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd., 1985. 4-7. Print.

SABC Digital News. (2013). Mbulelo Mzamane talks about the great Can Themba. [Online

Video]. 21 June 2013. Available from: https://www.youtube.com. [Accessed: 21 October 2016].

Themba, C., 1972. The Will to Die. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Themba, C., 1985. The World of Can Themba. Braamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd.

Zwane-Siguqa, Z. Ciccone, A. (2013). Remembering Can Themba [Online]. Available at

http://www.drum.co.za [Accessed: 21 October 2016].

Secondary

Bantu Education, Act No 47 Of 1953. 2016. PDF. Legislation. South Africa.

Chapman, M., 1989. Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s: The Text in Context. In: English in

Africa. Grahamstown: Rhodes University, pp. 19-29.

Johnson-Castle, Patricia. "Group Areas Act of 1950 | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. N.p., 2014. Web. 19 Oct. 2016. Available at http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/group-areas-act-1950

Kgositsile, K. (2013, June 21). “Speech by Professor Keorapetse Kgositsile on the Behalf of the

Minister Paul Mashatile at the Can Themba Memorial lecture”. Speech, Can Themba Memorial Lecture, State Theatre, Tshwane, Gauteng Province, South Africa, October 18, 2016. Available at http://www.gov.za. [Accessed: 20 October 2016]

Nicol, M., 1991. a good-looking CORPSE. London, Great Britain: Secker & Warburg.

"Pass Laws in South Africa 1800-1994 | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. N.p., 2011. Web. 20 Oct. 2016. Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/pass-laws-south-africa-1800-1994

Patel, E., 1985. Preface. In: The World of Can Themba. Braamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd, pp. 1-3.

End Notes

[i] Another source states that he was born in 1923. ↵

[ii] Essop Patel, preface to The World of Can Themba, ed. Essop Patel (Braamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd., 1985), 2. ↵

[iii] One of Themba’s friend remarks that Themba would only speak English or township lingo to not make his origins apparent. Mike Nicol, A good-looking Corpse, London, Great Britain: Secker & Warburg, 1991. ↵

[iv] Nicol, 179. ↵

[v] Nicol, 160. ↵

[vi] This university produced many South African legends including Nelson Mandela ↵

[vii] Keorapetse Kgositsile, "Speech by Professor Keorapetse Kgositsile on the Behalf of the Minister Paul Mashatile at the Can Themba Memorial Lecture" (speech, Can Themba Memorial Lecture, Pretoria, South Africa, June 21, 2013). ↵

[viii] Patel, 2. ↵

[ix] Kgositsile 2013 ↵

[x] Patel, 2. ↵

[xi] All non-White South Africans were required to carry passes, a kind of internal passport, with them at all times. These passbooks contained information about the bearer including name, age, work, etc. ↵

[xii] Pass laws in South Africa 1800-1994 2011. ↵

[xiii] Nicol, 368. ↵

[xiv] Themba, The World of Can Themba, ed. Essop Patel (Baraamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd. 1985), 104. ↵

[xv] A one-room flat on 111 Ray Street, Sophiatown ↵

[xvi] Nicol, 175. ↵

[xvii] Illegal brew houses ↵

[xviii] Themba, The World of Can Themba, 238. ↵

[xix] Patricia Johnson-Castle. “Group Areas Act Of 1950.” South Afrian History Online. Last modified October 04, 2016. http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/group-areas-act-1950. ↵

[xx] Union of South Africa“Bantu Education, Act No 47 of 1953” (Legislation, South Africa, 1953), 258-276. ↵

[xxi] Motjuwadi, 4. ↵

[xxii] Nadine Gordimer, "Can Themba" (speech, Can Themba Memorial Lecture, Pretoria, South Africa, June 21, 2013). ↵

[xxiii] Kgositsile 2013. ↵

[xxiv] Stan Motjuwadi, “The Man from The House of Truth,” in The World of Can Themba, ed. Essop Patel (Braamfontein: Ravan Press Ltd., 1985), 4. ↵

[xxv] Themba, The Will to Die 1972 (London: Heinemann Educational Books 192). viii. ↵

[xxvi] The Will to Die, viii. ↵

[xxvii] Nicol, 175. ↵

[xxviii] Nicol, 180. ↵

[xxix] Nicol, 181. ↵

[xxx] Nicol, 181. ↵

[xxxi] Kgositsile 2013. ↵

[xxxii] Kgositsile 2013. ↵

[xxxiii] Drum magazine was a popular form of media for the Black community ↵

[xxxiv] There is not a lot of information about Themba’s life at Golden City Post ↵

[xxxv] As quoted in Mike Nicol’s a good-looking Corpse. ↵

[xxxvi] Nicol, 179. ↵

[xxxvii] As quoted in Michael Chapman’s Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s: The Text in Context. Michael Chapman, “Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s: The Text in Context,” in English in Africa (Grahamstown: Rhodes University) 19-29. ↵

[xxxviii] Chapman, 22. ↵

[xxxix] Chapman, 22. ↵

[xl] Due to the dense population and mistreatment of Blacks, gangsters soon rose in the few freeholds that were given to the Black people. ↵

[xli] Nicol 1991, 174. ↵

[xlii] Nicol 1991, 178. ↵

[xliii] Nicol 1991, 182. ↵

[xliv] Father Ciccone, interview by Zwane-Siquga, Drum Digital, June 13, 2013. ↵

[xlv] Ciccone 2013. ↵

[xlvi] Mbulelo Mzamane, interview by SABC Digital News Employee, SABC Digital News, June 21, 2013. ↵

[xlvii] Ciccone 2013. ↵

[xlviii] It was usual for the South African apartheid government to declare anyone who went against them as communistic. The Cold War was taking place, so the title of communism was the easiest method of justifying the forbidding of a person from his own land. There are many famous South Africans, including Nelson Mandela, who were given this title. ↵

[xlix] Nicol, 182. ↵

[l] Patel, 2. ↵

[li] Themba, The Will to Die 1972, ix. ↵

[lii] Nicol, 182. ↵

[liii] The Order of Ikhamanga is a national order, and it is awarded to South African citizens for their accomplishments in arts, culture, literature, music, journalism or sport. Others who were awarded this include the famous singer, Hugh Masekela and novelist, Alex La Guma. ↵

[liv] Patel, 2. ↵

[lv] Henry Nxumalo was an investigative journalist in the apartheid times. He was commonly known as ‘Mr. Drum’ in reference to Drum magazine, for which he worked for. ↵

[lvi] Motjuwadi, 6. ↵

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project