George Hallett—More than Mandela

Abstract

George Hallett, a South African photographer is an artist who spent several decades living in exile. He left the country because of the continual hardships and injustices of the apartheid state. Hallett grew up in a fishing village outside of Cape Town where the influences from his teachers and friends opened up the world of artistic expression through the lens. Hallett spent nearly 30 years moving around the world and photographing the oppressed and their stories. He is most well known for his award-winning photography of Nelson Mandela during the election near the end of his time in exile. Hallett’s resistance documentary work focuses on the stories of those discriminated against in South Africa, and all across the world.

Key words

George Hallett, Photography, Documentary, Resistance, Apartheid, Exile, Artist, Mandela

Introduction

Most famously known for his internationally circulated photographs of Nelson Mandela during South Africa’s first democratic elections, George Hallett’s work began long before his involvement with the African National Congress (ANC), and his portfolio is much broader than that of one subject. Hallett’s career in photography was sparked by his childhood but really took off with his work in District Six, where he photographed the area before it was to be destroyed and rebuilt into a white area because of the Group Areas Act. Fleeing his home country, he travelled the world and photographed other South African artists that left their homes during apartheid. He also felt compassionate about other marginalised groups he encountered during his travels and his humanist photography of these groups amplified the voices of the oppressed—his photographs speak out against injustice by sharing the stories of his subjects. George Hallett’s background and experiences as a resistance photographer living in apartheid South Africa, and then going into exile, helped to create his humanist portrayal of the stories of the oppressed in South Africa, and around the world, and those he captured through the lens.

Hallett and Nelson Mandela

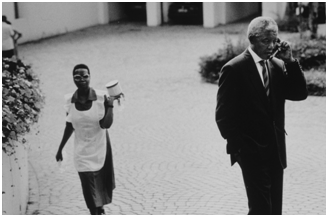

Mandela on the phone with de Klerk, 1994, World Press

Mandela on the phone with de Klerk, 1994, World Press

Hallett is best known for his photographs of Nelson Mandela. Some of the most iconic pictures of Nelson Mandela were taken by Hallett, because they showed him as a man, and not just an icon: Mandela talking on the phone, welcoming roaring crowds, thanking his supporters with arms wide ready to embrace them. When the world thinks of Nelson Mandela, they think of a smiling man, advocating for peace and for a loving, free, and equal South Africa. Hallett found himself faced with the task of portraying Mandela as “pensive and thoughtful,” and as a statesman prepared to handle governing a nation of hurting people[1] . In 1995, Hallett’s photographs of Mandela earned a Golden Eye World Press Photo Award[2] . Hallett’s photographs were published in a book, Images of Change, with over 140 black-and-white images of Nelson Mandela during the election[3] .

First Encounter with Mandela, 1994, MOMO

First Encounter with Mandela, 1994, MOMO

But these images of Mandela not only changed peoples’ perceptions of the ANC leader, but they helped to change the world’s perceptions of South Africa. They helped to “re-fashion…reflections about the ‘new’ nation” that aided the world in understanding what was going on during this complex and chaotic time in the nation’s history. After a 27-year ban on Mandela’s picture, Hallett’s images worked to “fill the empty…spaces” in the reconstruction of the new leader to give the world a fresh, evolutionary perspective of not only Nelson Mandela, not only the ANC, but of South Africa.

Background

Childhood

George Hallett was born in 1942 in District Six, an area of Cape Town, but he grew up with his grandparents in Hout Bay Village, a small fishing village in the Western Cape[4] . Hallett’s aunt and uncle, who also lived in Hout Bay, had a large impact on his intellectual development—as a young boy, his uncle’s library hosted magazines and books that were Hallett’s first source of artistic inspiration. His desire to become a photographer grew out of this early inspiration, and also the movie nights his school would host on the weekends. Here, Hallett developed his talent for “becoming the camera”—playing the role of the observer, allowing the “reality in front of you” to commence without the observer’s direction.[5]

Another influence on Hallett’s future photography career came from his interactions with his teacher, Richard Rive, and his teacher’s friends, Afrikaans writers and artists[6] . His family could not afford to send him to university, so his “university was out in the streets”—the knowledge that he gained about the world and about art came from his friendships with artists like James Matthews and Peter Clarke. These friendships exposed Hallett to more photographic works, as well as the discriminatory nature of newspapers and magazines, which did not display pictures of people of colour. During this period in his young adult life, in the early 1960s, Hallett became, in his words, “a man of the world” gaining his inspiration to become a photographer[7] .

Early Career

Hallett began his early career as a photographer on the streets where he learned to be bold and defend his practice[8] .He started after his friend from high school, Clarence Coulson, insisted that, instead of criticising his work, he should get his own camera and work for the same man Coulson worked for and practice street photography. Hallett walked through the streets, stopping and asking strangers if they wanted their pictures taken—unstable, low paying, unrewarding work.

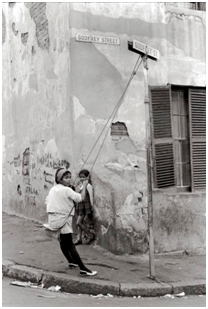

Godfrey Street, District 6, MOMO

Godfrey Street, District 6, MOMO

Hallett’s first big documentary photography project came when he photographed District Six after it was declared a white area and before it was destroyed and recreated. His friends, Matthews and Clarke, suggested that he go and document the sights and people of the District Six area. He went every Saturday to take photos of his birthplace before it was lost and recreated into something else—the government stripping away this tangible part of Hallett’s identity. His story has parallels with other South Africans not in the government’s favour—their opportunities limited, pieces of their identity stolen, and their lives tainted with the stains of discrimination and segregation. An artist like Hallett not only has to live through his story of oppression and discrimination, he also has to relive these experiences every time he shares his stories, and the stories of others like him through his art.

Exile

Not much other than what has been included in this biography is known about George Hallett’s personal life and background. Hallett has not given many interviews, and there are very few photographs of him on the Internet. He has managed to keep much of his personal life private. On the topic of his going into exile, Hallett does not delve much into the reasoning behind his decision to leave South Africa. Around 1970, Hallett decided that living in South Africa was too much and not enough[9] . For Hallett, his career in photography was not enough—only getting to take pictures after work and in his free time did not satisfy his desire to photograph the people and themes he wanted. At the same time, living in South Africa became altogether too much—the insults, the harassment by the police, the belittling, the inability to stand up for his rights, the anger and frustration with the systematic discrimination and oppression in an apartheid regime. Hallett says that living in South Africa had become “intolerable” and that the anger inside of him was “ugly” to look at[10] . He had many friends who had already left, and in 1970, and he decided to follow suit.. The next 24 years Hallett lived in exile, moving to several different locations until the end of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela.

London

Hallett arrived in London in 1970 where he began working for the Times Higher Education Supplement as a photographer[11] . He also began creating covers for Heinemann books and created the African Writers Series portfolio portraits for 16 outstanding writers as a piece of publicity for Heinemann[12] . He worked as a freelance photographer for Heinemann for 12 years, creating covers and portraits, where, for the first time, he was allowed to express himself freely[13] .

As a South African photographer in European society, Hallett learned how crucial relationship building was to his practice. In order for people to open up their homes and their lives to be documented, a photographer had to earn his subject’s trust. Hallett spent much of his time in the communities he wanted to photograph, sharing his life and struggles with the people, and in turn, getting to learn about and record real people’s lives and stories[14] .

France

In 1974, Hallett left Britain for France after being accused of being apart of a terrorist organisation that was killing South African spies[15] . One day while he was living in London, Hallett got a call from an inspector from Scotland Yard, the police service responsible for protecting and monitoring most of London[16] . The inspector accused Hallett of assassinating South African spies and running a terrorist organisation—accusations based off information Hallett believes to have been planted.

Peter Clarke's Feet, Gallery MOMO

Peter Clarke's Feet, Gallery MOMO

Already in exile, Hallett decided it was time to move from yet another country where he felt threatened and in danger. He left for France to go for a holiday and stay with a mutual friend, Lilli, who he fell in love with and married[17] . He would commute to London to work on his book covers, but in France, he spent his time farming and photographing for pleasure and leisure. During his time in exile, Hallett continued to meet other South Africans in exile and photograph their stories and struggles. Even during his time in a remote French village, he found the time to photograph artists and friends like Peter Clarke and James Matthews.

Zimbabwe and the US

Eventually, Hallett’s relaxed lifestyle in France began to bore him—he was a man of movement and competition, a man meant to photograph and teach about the struggle and resistance that had driven him out of his home country. In 1980-1981, he went back to Africa in order to be close to his dying father and to teach photojournalism[18] . Hallett spent time with friends and family in Cape Town before his father died, and worked on a few smaller projects during his short time back home. However, his marriage to a German woman, Lilli from France, “created a huge problem” for supporters of apartheid—Hallett felt like he was being watched and spied on by the government, so after his father died, it was time to leave again.

Hallett moved to Zimbabwe to photograph and display exhibitions of his work both from his time in exile and from his time in South Africa[19] . However, no matter where he moved, his life was still marked by constant monitoring and infiltration by spies. He was accused of teaching his politics instead of teaching purely photojournalism and his classes were spied on, which made Hallett feel as if the environment in Zimbabwe was “’…worse than apartheid.’” When Hallett was offered a job in the United States, he took it. In the 1980s, Hallett worked at the University of Illinois where he taught photography. His experiences allowed him to travel around the country and connect with minorities in America, to share with them the struggles and stories of South Africa, and to teach them about the tool of photography.

Amsterdam

When Hallett decided to leave the United States, he knew that his marriage with Lilli was breaking up[20] . After the end of their relationship, Hallett moved to Amsterdam where he had several exhibits, photographed plays, worked with the media, and taught photography to young Turkish and Moroccan women[21] . Here, Hallett discovered a whole new world of exiles beside the world of his own country. He photographed people from the Islamic world living in Amsterdam, people who ran away from the fear and hate-driven culture of their country to find peace and safety—a plight much like his own.

His Return

Before his official return to South Africa, he was commissioned by an agency in Paris to photograph the violence between Inkatha and the ANC[22] . He spent his timing photographing the military and their rallies, their camps and training, and taking pictures of the conflicts in the rural areas. He then went to Cape Town to spend a week with the Archbishop Desmond Tutu and photograph parts of his life that people had “never seen before.” After he returned to France, Pallo Jordan called him and commissioned him to photograph the first democratic elections in South Africa’s history[23] . His images of Nelson Mandela during the election were published in his photograph book, Images of Change.

After the election, Hallett returned to Paris. When he finally came back to South Africa to stay, it took Hallett two years to adjust to life in South Africa. Hallett had gone from being a man of the world, travelling internationally, free of the racial binds of apartheid, free to photograph whatever he wanted to, to living in a nation still struggling to overcome the legacies of apartheid. In South Africa, although the legal framework of apartheid had been denounced, the “old-fashioned mind-set” persisted, and anger and hatred loomed over the country[24] . In 1997, Hallett became the official photographer for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the program implemented to restore justice to victims of apartheid crimes through televised court-like hearings from victims and requests for amnesty from perpetrators[25] .

Resistance photography 1946-1976

In order to understand Hallett’s development as a photographer, an understanding of resistance photography is crucial. In apartheid South Africa, photography became a medium of resistance—with the camera as a weapon in the battle against discrimination and oppression[26] . Resistance photography, or political photography, documents the “conflict between oppressed and oppressor from the perspective of the subjugated”[27] . Around the time Hallett left South Africa in the mid-1970’s, resistance photography could be divided into two categories: photojournalism and social documentary photography[28] . Photojournalists documented the resistance in action—photographing violence, and active nonviolence, with access to scenes and events. Social documentary photographers, a category to which Hallett’s photography prescribes him to, told people’s stories and revealed the injustice of South Africa. The power of photography helped mobilise international support for the ANC and other opposition groups. To hear the plights of the oppressed is one thing, but to see the horrific impacts of a government program has the ability to inspire uprisings and massive resistance. Photographs captured the truth behind the deceit the government tried to cover up—pictures shown internationally made other countries question and withdraw their support of the apartheid regime. The impact of photographs that circulated around the world sparked “worldwide condemnation and sanctions” that contributed to the collapse of apartheid in South Africa[29] .

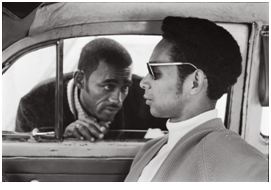

Debt Collector, MOMO

Debt Collector, MOMO

Hallett’s humanist approach to photography allowed him to focus on the people in his photographs, their stories and their everyday lives[30] . His photography lends to a social documentary portrayal of the struggle—by telling his subjects’ stories, Hallett captured stories of racism, discrimination, oppression, injustice, inhumanity, and violence. However, as so many others before and after him, Hallett soon discovered not only the hardships, but also the dangers, of being a struggle photographer in apartheid South Africa[31] . Cameras were confiscated, photographers were often harassed, bullied, and faced the potential of being intentionally or accidentally harmed during intense conflict situations. Photographers were often mistrusted—their intentions unknown to their subjects or by those who doubted their political affiliations. For those oppressed by the systems they lived in, to have their stories documented with the potential of display, or worse, exploitation, scared people. With the culture of fear instilled by the government, people often battled an internal struggle over whether to open up to others, or to stay closed within. Resistance documentary photographers, like Hallett, often had to build relationships with people in the communities they worked in to build trust.

Photography in Exile

Hallett’s humanist, documentary style of photography is pervasive through almost every one of his works. However, another of Hallett’s photographic characteristics was his humility. When Pallo Jordan was asked why Hallett was chosen for the crucial job of photographing Nelson Mandela during the first democratic elections, he said, “You’re the best. But the other thing I like about you is that you make yourself invisible. You bury your ego, and that’s what I wanted”[32] . As a man always behind the camera, Hallett says that he “’prefers] being a fly on the wall’”—the “invisible” photographing the forgotten and ignored communities across the world[33] . He photographed marginalised groups in Europe, including the Moroccans and ‘peasants’ in France, the hippies in conservative English towns, and racial mixing in Paris and Amsterdam. Hallett also stayed true to his South African political roots by working with other exiles. From political activists like Pallo Jordan, to painters like Dumile Feni and musicians like Abdullah Ibrahim, Hallett never let the politics of South Africa fall far from his focus.

Recent Work

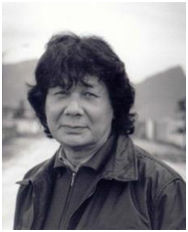

George Hallett, SAHO

George Hallett, SAHO

More recently, post-apartheid South African galleries and museums welcome Hallett’s work. In 2014, the Iziko South African National Gallery exhibited Hallett’s exhibit, A Nomad’s Harvest. This exhibit was a testament to his travels across the world during his time in exile—from London to Paris, Amsterdam to Tokyo, Italy, Cameroon, Morocco, Zimbabwe, to the United Stated[34] . As one reviewer suggests, Hallett’s photographs capture “the beauty of living, yet forever mindful of injustice and its deleterious effects” of human life and communities discriminated against—from the townships in South Africa to the “farthest corners of the world”[35] . Shown through this exhibit, Hallett always tries to convey the “positive images of humanity”[36] . His vision is never blurred by constructs of race or status—Hallett concentrates on the “beautiful things in life” that effectively make viewers feel the “warmth of humanity.”

Conclusion

George Hallett’s legacy is far more than just his work with Nelson Mandela in 1994. His story began when he was born into apartheid South Africa, where he would be inspired to live a life devoted to conveying not only the struggles of the survivors, but the strength of the oppressed, the good in people and the richness of their stories. When we think about George Hallett, we think about the iconic and award-winning imagery of Nelson Mandela shouting “Amandla!” and broadly smiling at his supporters. But we should also think of a man who battled apartheid himself. We should think of a man who traversed the world representing people and their stories, giving them a voice through his photography. George Hallett is a man whose background and experiences, leading to his exile, allowed him to use his photography as a way of sharing the tales of peoples’ struggles and triumphs around the world.

Bibliography

Currey, J. (2008). Africa Writes Back. Oxford: James Currey. Print.

Jayawardane, N. (2013). The Photographer who Showed Nelson Mandela to the World. Africa is a Country. [online]Available at: africasacountry.com [Accessed 18 October 2016].

Johns, L. (2014). Photographer George Hallett Captures the ‘Dignity’ of Apartheid. The Root, pp. 1-2. [online] Available at: theroot.com [Accessed 16 October 2016].

Kamaldien, Y. (2014). George Hallett: I Prefer Being a Fly on the Wall. Mail & Guardian: Africa’s Best Read. [online] Available at: mg.co.za [Accessed 18 October 2016].

Kleinsmith, M. (2014). A Nomad’s Harvest: A retrospective exhibition of photographs by George Hallett. Iziko Museums of South Africa: Iziko South African National Gallery.[online] Available at: iziko.org.za [Accessed 20 October 2016].

Krantz, D. (2008). ‘Politics And Photography In Apartheid South Africa.’ History Of Photography 32, no. 4, 280-300.

Mason, J. (2014). An Interview with George Hallett. Social Dynamics 40, 199-214.

Scaldaferri, G. (2014). George Hallett: Photographing South Africa’s Greatest Son. The Culture Trip. [online] Available at theculturetrip.com: [Accessed 24 October 2016].

South African History Online, (2016).Photography and the LiberationStruggle. [online] Available at: sahistory.org.za/article/resistance-photography-and-mobilization-resistance-1946-1976[Accessed 27 October 2016].

Staffordshire City Council. (2016). Connecting Histories. [online] Available at: search.connectinghistories.org.uk [Accessed 17 October 2016].

The Gallery MOMO. (1942). George Hallett. [online] Available at: gallerymomo.com [Accessed 17 October 2016].

1995 World Press Photo Contest. (1994). People in the News, Third Prize Stories. [online] Available at: worldpressphoto.org [Accessed 17 October 2016].

End Notes

[1] Graziano Scaldaferri, “George Hallett: Photographing South Africa’s Greatest Son,” The Culture Trip, 2014, accessed October 17, 2016,theculturetrip.com. ↵

[2]“People in the News, Third Prize Stories,” accessed October 17, 2016, worldpressphoto.org. ↵

[3] Neelika Jayawardane, “The Photographer who Showed Nelson Mandela to the World,” Africa is a Country, 2013,accessed October 18, 2016,africasacountry.com. ↵

[4] John Edwin Mason, “An Interview with George Hallett,” Social Dynamics40 (2014): 200. ↵

[5]Ibid, 201. ↵

[6]Ibid, 202. ↵

[7]Ibid, 203. ↵

[8]Ibid, 204. ↵

[9]Ibid, 205. ↵

[10]Ibid, 205. ↵

[11]Ibid, 206. ↵

[12]James Currey, Africa Writes Back. (Oxford: James Currey, 2008). ↵

[13]Mason, 206. ↵

[14] Lindsay Johns,“Photographer George Hallett Captures the ‘Dignity’ of Apartheid,”The Root, April 26, 2014, accessed October 16, 2016, theroot.com. ↵

[15]Ibid, 209. ↵

[16] Yazeed Kamaldien, “George Hallett: I Prefer Being a Fly on the Wall,” Mail & Guardian: Africa’s Best Read, March 14, 2014, accessed October 18, 2016, mg.co.za. ↵

[17]Mason, 209. ↵

[18]Mason, 209. ↵

[19]Mason, 210. ↵

[20]Mason, 211. ↵

[21]Mason, 211. ↵

[22]Mason, 211. ↵

[23]Mason, 212. ↵

[24]Mason, 213. ↵

[25] “Staffordshire City Council: Connecting Histories,” accessed October 17, 2016, search.connectinghistories.org.uk. ↵

[26]“South Africa History Online: Photography and the Liberation Struggle,” last modified August 19, 2016, accessed October 17, 2016, www.sahistory.org.za/article/resistance-photography-and-mobilization-resistance-1946-1976. ↵

[27] David L. Krantz, “Politics And Photography In Apartheid South Africa.” History Of Photography 32, no. 4, (2008): 290. ↵

[28]“South Africa History Online,” www.sahistory.org.za/article/resistance-photography-and-mobilization-resistance-1946-1976. ↵

[29]Krantz, 290. ↵

[30] “The Gallery MOMO: George Hallett,” accessed October 17, 2016, gallerymomo.com. ↵

[31]Krantz, 290. ↵

[32]Mason, 214. ↵

[33]Kamaldien, “Fly on the Wall.” ↵

[34]Johns, “‘Dignity’ of Apartheid.” ↵

[35]Ibid, Johns. ↵

[36] Melody Kleinsmith, “A Nomad’s Harvest: A retrospective exhibition of photographs by George Hallett,” accessed October 20, 2016, iziko.org.za. ↵

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project