Introduction

In the years following 1994, South Africa has become well known for its culturally diverse population and heritage (Fraser, 2005:11). The ways in which this diversity manifests varies and is dissimilar throughout the country. In the popular tourist city of Cape Town, one of the ways in which it may be observed is in the annual Minstrel Festival which takes place on 1 January, and is also referred to as Tweede Nuwer Jaar (Second New Year). During the festival thousands of brightly-clothed people march through the streets of Cape Town, organized into Klopse (troupes), entertaining the crowd through singing, dancing and playing a number of musical instruments. This festival has become an integral part of Cape Town popular culture and it is important to understand its history and significance within the broader South African historical context and narrative. That being said, this article will discuss the evolution of the festival, the terminology used to describe it as well as its relevance to South African history.

Slavery in the Cape - a brief overview

An illustration of freed prized slaves celebrating with a ghoema-style drum and shaker (Meltzer et. al., 2012:2).

An illustration of freed prized slaves celebrating with a ghoema-style drum and shaker (Meltzer et. al., 2012:2).

A comprehensive understanding of the minstrel festival requires an understanding of the socio-historical and political context in which the festival originated. The Tweede Nuwe Jaar carnival as it is known is a tradition which was established more than a century ago and may be dated back as early as 1907. However, it is maintained that its social roots can be traced back even further - entrenched in the experiences of those who were forced into colonial slavery. It is thus important to note that this merry carnival has its roots in South Africa’s painful past of colonial rule, racial prejudice and segregationist policies whilst highlighting the ways in which oppressed people resisted such notions.

The roots of slavery in the Cape can be traced back to as early as 1652 when the first officials from the Dutch East India Company settled there. Reaching Table Bay in 1653, Abraham from Batavia became the first slave to be imported. Even though the slave trade was banned in 1808 by the ‘British Crown,’ it was only in 1834 that slavery was abolished. Even so, liberated slaves had to serve an apprenticeship between 1834 and 1838, in order to facilitate their transition into society and make sure that they are “prepared” for freedom. It is estimated that between 1652 and 1808, 63 000 people were brought to the Cape and enslaved, with as many being born into slavery. In 1834 there were 36 169 slaves at the Cape.

Slaves hailed from different parts of the world. It is maintained that 26.4 percent came from Africa – mostly from Mozambique, West and Central Africa. During the early years of colonisation; 25.9 percent of the slaves came from India – specifically from Bengal, Malabar, Coromandel and Ceylon. A further 22 percent of the slaves came from areas that make up modern-day Indonesia. It’s important to note that during the early period of slavery the Dutch East India Company forbade the enslavement of the aboriginal people; the Khoikhoi pastoralists and Bushmen hunter-gatherers from the Cape and neighbouring regions. This necessitated enslaving people from other parts of Africa. However, later people from the East were captured and enslaved. Many were forced to be labourers and servants to the company and while others became farmers.

The abolition of the slave trade in 1808 meant that slaves could no longer be imported. However, 5 ,000 “prized negroes” were brought to the Cape between 1808 and 1856 These captives were loaded on ships bound for the Americas where they were to be sold, but the British Royal Navy often intercepted these ships and brought their human cargo to the Cape. This specific group was “apprenticed” for fourteen years. After 1934 they were employed as domestic or farm workers. Some of the slaves were housed at the Company Lodge, and were regarded as the property of the Company. After 1692 though, most of the slaves were privately owned by colonists and were employed as domestic servants, farm workers or as artisans. Since the slaves were from different regions they had very little or nothing in common, apart from their experience of slavery. Eventually the number of slaves born at the Cape outnumbered imported slaves and as of 1770, their shared experience became the foundation on which they could construe their environment and also their lives (Shell, 1994:404).

It is argued that the dehumanizing of the slaves contributed in a number of ways to preventing the formation of a collective consciousness. People were abducted and enslaved, deprived of their freedom and separated from their families and everyone-else with whom they shared the same notions of life. When they were relocated, they were given new names (Martin, 1999:51). They were forced to serve foreign people as their masters and to live alongside other enslaved people from different parts of the world, with whom they did not share the same language or customs. Consequently, it was impossible for them to reconstruct communities similar to those in their countries of origin. What aggravated the situation is the fact that slaves were treated differently. The physical features of a slave as well as their place of origin in some cases meant that they were treated better than others. As a result, some slaves had more comforts than others and on occasion some slaves were given authority over other slaves (Martin, 1999:51-52).

Slavery brought different people together in the setting of the home. Each slave was exposed to each owner and each settler to each slave on a very intimate footing. There was, in fact, a common reciprocal legacy, a legacy which is the as yet unexamined creole culture of South Africa, with its new cuisine, its new architecture, its new music, its melodious forthright and poetic language, Afrikaans, first expressed in the Arabic script of the slaves’ religion and written literature - Robert Shell (1994)

Cape Society

A Creole Culture

Given the fact that the slaves were from different parts of the world, they contributed uniquely to the eclectic society that evolved at the Cape. It was a melting pot of cultures incorporating and blending features of African, Asian and European sub-cultures. This resulted in the formation of a Creole society in Southern Africa, similar to other countries such as West Indies and parts of the Americas. The dominated, enslaved groups where subsequently characterized by an amalgamation of the different aspects of each culture, which has been passed down from one generation to another. This meant that slaves eventually created a culture of their own, completely different to that of their masters. Regardless of it being different, the world of the slaves was consequently never completely cut off from the dominant culture. Instead, it continued to interact with it, resulting in shared-shaping of traditions and practices.

The ‘Creolization’ of Cape Town was particularly evident when people met and interacted with each other. Furthermore, because of the dependence of its harbour, Cape Town eventually became known as the ‘tavern of the seas’. Sailors and colonists who travelled between Holland and Batavia stayed here for several weeks at a time. During their stay-over, they could enjoy boarding houses, restaurants and other places of pleasure. It is also important to note that before abolition of slavery, there were certain residential areas that were mixed. People from different parts of the world lived together and so-called ‘free Blacks’ were allowed to work alongside White people in the same jobs. It is maintained that slaves were well integrated into the social life of the underclasses. In the taverns, canteens and unlicensed bars, free Blacks socialized with sailors and White Capetonians. The ‘Creolization’ of the Cape was thus also influenced by outsiders.

It was against this backdrop that the New Year festival developed, which was also the onset of a street culture in Cape Town. Capetonians were very fond of processions and parades and by the mid-nineteenth century groups would go from bar to bar with burning torches, making music. However, this was not welcomed by everyone. In 1803 a regulation was passed banning private music bands or any other form of musical assembly from playing in the streets after sunset or before sunrise. This subsequently resulted in a lack of organized entertainment in Cape Town during the time of slavery. Permitted musical entertainment was mostly provided by the military, while other types of entertainment were provided by the taverns. Also, the absence of theatres and organised entertainment further fuelled the development of a street culture, since this was the only other space where people could join together to organise informal processions, observe parades and create music.

Celebration of New Year

The celebration of New Year has always been a big event at the Cape, and its Dutch influence is clearly witnessed. During the seventeenth and eighteenth century in the Netherlands, Twelfth Night was the most popular festival. Celebrated on 5 or 6 January, this was the festival of the Magi who allegedly followed a star to the birth-place of Jesus Christ. It is believed that some aspects of this celebration were maintained in the ways in which New Year was celebrated in the southern hemisphere. They include going from house to house providing serenades while accepting certain gifts such as bread and pancakes. Also, those serenading would carry a paper lantern in the shape of a star lit by a candle, called star singers.

This Dutch celebration first included South African slaves in 1674 when the governor at the time, Isbrand Broke, desired the slaves to be part of the celebration on 1 January of that year. They were instructed to refrain from work, and were offered money, clothing and tobacco. Cannons were fired from the Castle of Jan van Riebeeck as well as from the ships that were anchored at Table Bay. Furthermore, farmers from the interior travelled to Cape Town with their slaves to spend time with relatives in the city, and it is maintained that street parades and serenades formed part of the celebration. By the early nineteenth century New Year was the most joyous occasion of the year, particularly for slaves as it afforded them the opportunity to engage in festivities. It therefore comes as no surprise that when slavery was abolished in 1834 and the apprenticeships ended in 1838, it was greeted with much celebration, street processions, music and songs. This celebration formed the foundation on which the subsequent New Year festival of Cape Town would develop.

From Slaves to Coons

Over time slaves managed to establish families and social networks despite the significant control exercised over their lives by the colonial authorities. They especially enjoyed dancing and playing music at picnics and weddings in an attempt to foster social cohesion amongst each other. Apart from a small number of slaves who committed suicide in response to their lives of oppression and dehumanisation, most slaves were resilient and looked to ways that would make their lives more bearable, both physically and spiritually. As a result, slaves enjoyed what liberties they could, whilst innovatively developing strategies and traditions to ensure happier futures for their children. These innovations drew on their memories and aspects of their cultures brought from their countries of origin as well as certain mannerisms which belonged to the non-slave people with whom they had interacted.

According to Winberg (1992:78), one of the earliest references made to an innovation was the so-called ghoemaliedjie (‘ghoema song’). It is attributed to a male slave named “Biron”. He would later be punished for singing ditties “half in Malay and half in Dutch” in the streets of Cape Town, which were deemed dubious. This is because the song would most likely have been a satirical commentary on the mannerisms of their “white masters and madams”. These ghoemaliedjies were always sung at picnics, an event which slave masters were obligated to provide the slaves with. For this reason ghoemalidjies have become known as a Malay picnic song, a straatlied (street song), or a skemliedjie (comic song).

According to Fakier (1988), when slaves first arrived at the Cape, they attempted to deal with their sense of melancholia by going to the beach on a Sunday afternoon and beating on the ghoema drum. This ghoema-drum tradition and the mish-mash of dance steps used by troupes during recent New Year’s festivals may also be traced back to the influences of the slaves, who often imitated dances of their British rulers. These dances include the lances, the squares and the quadrilles. Slaves, freed slaves, and those who were descendant of Khoi-San people would also sing in choirs, watch the colonial troops march on parade, sing “God Save the Queen,” and celebrate marriages and birthdays with song and dance. All these influences innovatively were blended into new traditions and passed down from one generation to another.

After emancipation in 1838, freed slaves and their descendants formed dance bands which were in demand across all classes during the nineteenth-century in Cape Town. Even though they mostly played European dance music before and after emancipation, there was some other music played by Coloured musicians. Subsequently there were some Creole repertoires which developed, mixing Eastern musical elements with European elements. At the New Year, slaves were always given a holiday. As one would expect, it was a joyous and much-celebrated occasion. They dressed up in brightly-coloured and eccentric costumes, and also sang and danced. This subsequently became a tradition, which was maintained well after emancipation. Emancipation was henceforth celebrated by street parades which were accompanied by bands.

The Influence of American Minstrelsy

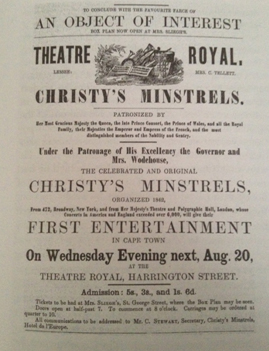

An advertisement in The Cape Chronicle for the appearance of Christy’s Minstrels on 20 August 1862 at the Theatre Royal (Martin, 1999:79).

An advertisement in The Cape Chronicle for the appearance of Christy’s Minstrels on 20 August 1862 at the Theatre Royal (Martin, 1999:79).

At the end of the nineteenth century the ways in which New Year was celebrated in Cape Town, especially among coloured people, would be significantly influenced by American ‘blackface’ minstrelsy. American minstrel troupes were initially comprised of white comedians, singers and musicians, and during their performances they would impersonate African American slaves from the south. Using burnt cork, they blackened their faces. They also wore very eccentric clothing such as colourful tailcoats when they impersonated the more stylish societal figures and rags as their impersonations turned to rural slaves. Humorous skits, the singing of “negro” songs as well as playing instruments such as the violin and banjo were considered essential elements of their act. Within this context, participants were referred to as coons, a racist term which referred to the inferiority of the slaves. Despite the negative connotations attached to this term, many troupes today still prefer to use this term, many without knowing what the term means.

It is maintained that the songs from American minstrel shows were sung at the Cape, even before they were staged in the U.S. This involved groups of Malay men, who would walk up and down the streets while singing certain Dutch (and on occasion, American) songs “in perfect harmony.” Soon, certain bands of singers formed “serenaders” such as the Celebrated Ethiopian Serenaders in 1848. In 1860 these serenaders even sung for Prince Albert upon his visit to the Cape; and on 11 March 1861 they were part of the “Grand Entertainment” at the Theatre Royal in Harrington Street. The appearance of Christy’s Minstrels alongside the Celebrated Ethiopian Minstrels revolutionized Cape Town entertainment in August 1962.

The formation of minstrel societies

In the late 1800’s there was an emergence of local minstrel acts in Cape Town, such as the Amateur Darkie Serenaders and the Darkie Minstrels. In 1887 many concerts were held in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, with many local minstrel ensembles performing. However, it is important to note that the Cape Town Coon was adapted to fit into the local context. This is evident in the acts of the 1869 performance of the Amateur Coloured Troupe. For example, it included Malingo Hoy, the Cape Town Coolie (which was Dutch-Mozambique lingo) and A jolly place is Cape Town.

The Jubilee Singers, an African American minstrel group was especially influential in shaping the minstrel culture in South Africa. They performed in the country during the 1890’s (Meltzer et. al., 2010:4).

The Jubilee Singers, an African American minstrel group was especially influential in shaping the minstrel culture in South Africa. They performed in the country during the 1890’s (Meltzer et. al., 2010:4).

By the 1870’s there were a number of societies, which existed among the Coloured people of the Cape. They included sporting groups and singing societies as well as sports clubs that paraded on New Year’s Eve. It is maintained that the first New Year Carnival troupe was organized in 1887, called the Cape of Good Hope Sports Club. It was also a singing society and on New Year’s Eve members of this klops (club) appeared in black face and minstrel costumes. The march was poorly attended and the help of the police was enlisted to maintain order to escort what essentially became a lantern bearing procession. On New Year in 1888 those who were employed by a baker in Loop Street walked across town to their annual picnic with the accompanied by a band of musicians (Martin, 1999:91). Whilst these may appear to be seemingly insignificant events, it could be seen as some of the first attempts at New Year festival celebrations in Cape Town.

The Carnivals in twentieth century Cape Town

Competitions

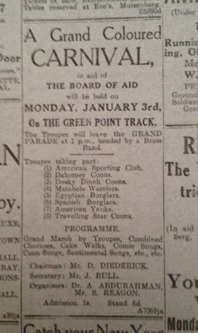

An advertisement in the Cape Times on 1 January 1907 for the first carnival competitions held at the Green Point Track (Martin, 1999:99)

An advertisement in the Cape Times on 1 January 1907 for the first carnival competitions held at the Green Point Track (Martin, 1999:99)

Cape minstrels group performing at the Green Point Track in Cape Town, 1907 (Martin, 2000:366).

Cape minstrels group performing at the Green Point Track in Cape Town, 1907 (Martin, 2000:366).

By the 1900’s New Year celebrations in the streets of Cape Town was a common occurrence. There was also a measure of competition which came into being between seranaders, clubs and bands even though competition remained informal. It happened in the streets without judges or reward. The performances were mostly intended for the listeners and to gain their approval as well as some popularity. It was not until 1 January 1907 that the first competitions were organized by the Green Point Cricket Club at the Green Point Track. The last carnival happened in 1909. It was less successful than the ones that preceded it, possibly due to a lack of money, and became more of a “show” (Martin, 1999:103). Carnivals were discontinued until 1920, when the leader of the African People’s Organization (APO), Dr A Abdurahman decided to organize a “Grand Carnival on Green Point Track”. It was a huge success and the event was held again the following year. A rival carnival was held at Newlands in 1921 and from that year onwards, competitions took place every year at various venues. Various boards organized it and it attracted very big audiences, which resulted in it becoming a big commercial affair (Martin, 2000:366).

The carnival organized by the APO in the Cape Times on 1 January 1921 (Martin, 1999:104)

The carnival organized by the APO in the Cape Times on 1 January 1921 (Martin, 1999:104)

Rivalry

In 1921 rivalry broke out between the Cape Town Cricket Club and the APO, when the former decided to hold its own carnival again at the Green Point Track, which was reserved by the APO. The APO then had to rent the Western Province Rugby Grounds at Newlands. The Cape Town Cricket Club boasted in a number of different troupes in flamboyant attire; such as the Irish Princes, whose uniform incorporated straw with white feathers. The APO on the other hand made quite a profit and managed to donate just over 100 pounds to the Cape Town and Wynberg Board of Aid. The organizers continued to compete for the largest audience, best troupes and for the best venues (Martins, 1999:106).

Segregation

Another feature of the carnival at the time was the reservation of seats for white people at venues such as the Green Point Track, which cost three times as much as a regular ticket. This was in stark contrast to the way in which the carnival was experienced on the street. Newspaper articles about the street carnival frequently made mention of the fact that “young white and coloured people” participated in the occasion and that “there was no colour distinction in the riot of the merriment” but that “all nationalities in the peninsula were represented”. The family members of the troupes often ended up sitting or standing in positions where they could only notice the backs of the trouped, which led confrontation at some points (Martin, 1999:108).

Change during the 1920’s and 1930’s

While most of the troupes had names inspired by American minstrelsy, such as the Happy Boston Coons, troupes that emerged at this time had more localized names such as the Cape Town Hawkers and the Grand Parade Darkies. At this time the troupes were also small in size and ranged from 30 to 70 members. The uniforms were also given more attention and it was cut to the sizes of the participants and fitted individually. These uniforms were kept secret until New Year’s Eve and it is reported that tailors worked behind locked doors and even blindfolded Coons during their fittings. The uniform was in the official colour of the troupe. It usually consisted of a top hat, a tailcoat, a shirt and a big bow tie, a pair of trousers, socks and shoes. They were accompanied by a stick, which they stomped to the ground as they sang and marched to the beat of the music (Martin, 1999:114).

The Carnival during Apartheid

Even though the carnival had become part of Cape Town tradition at this point, it was not isolated from the ensuing political context, which had a big impact on the festival. After the Group Areas Act was passed implemented in Cape Town in 1951 the areas where the Coons were allowed to compete were now off-limits to them, because they were located in “white areas”. They were instead showed to other venues such as Athlone Stadium in 1971. Not only were the locations changed but the competition itself also became a segregated arena and there were attempts to change the ways in which the carnival was organized as well as the content thereof. Those who participated in the march were of the opinion that Cape Town belonged to them, that they were part of its history and that marching through the streets of Cape Town was how they tried to affirm and maintain their place in the city’s history (Martin, 2000:376).

However, the troupes remained resilient and the festival culture continued to develop, albeit within the overcrowded, dilapidated and poverty stricken area of District Six. This is where many coloured families in Cape Town resided at the time. People socialized in the streets and created forms of expression of their own. More importantly is how the community managed to preserve their love for music. Malay choirs as well as Coons rehearsed and performed in the streets while also influencing the Cape Town Jazz subculture, which developed after World War Two, through the incorporation of the ghoema beat into jazz music (Martin, 1999:135). So while there were attempts at interrupting the development of a culture specific to the coloured people of Cape Town, it continued to develop within the boundaries they were forced and limited to exist in.

Another change that took place after the advent of Apartheid was the costumes worn by troupes. During the 1950’s and 1960’s the costumes became more standardized. This is because more people joined the troupes and a standardized uniform meant that they would save on the cost thereof. They also did away with tailcoats, which were now replaced with smaller jackets and also made use of synthetic material instead of satin or cotton. The music also changed to include more popular music such as Frank Sinatra’s songs. Also, instead of string bands troupes were now accompanied by brass bands (Martin, 1999:136). The carnival also became more commercialized which further influenced the music. Troupes paid professional artists to participate in the carnival. Those who were unable to enlist their services had to look for sponsors, which meant that carnivals now became a business. By 1960 there were five organizing boards whose promoters were intent on making profit from competitions. Coons, captains and performers felt that they were being exploited. In 1961 the captains of 21 troupes decided to form the South African Carnival Board, but they failed to maintain it (Martin, 1999:142).

The growing strain on the Coons from Apartheid and the commercialization of a tradition that was kept alive for many years eventually began to take its toll. It is maintained that by 1968 there were virtually no troupes in Cape Town in January. This is because Green Point was demarcated as a white area and a permit for a multiracial audience to attend the Carnival there had been refused. Troupes were instead taken by bus or lorry areas such as Goodwood (Martin, 1999:150-151). This was a very sad development as the Green Point Track was where the marching traditionally took place. It also meant that some of the most important aspects of the carnivals would be scrapped. This included the marching of the troupes through the streets while singing, dancing and making music which was part of the heritage of the community; the opportunity to watch the coons without having to pay which meant that the festival became inaccessible to the poor; as well as the opportunity to remind South Africa of the contribution of the ancestors of Coloured people to Cape Town culture (Martin, 1999:150-151). Finally, in 1977 Coon marches anywhere in Cape Town were banned only to be allowed back into the city in 1989 (Martin, 2000:376).

The Coon festival post-Apartheid

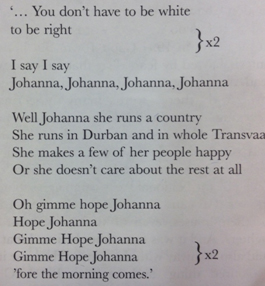

The lyrics to Give me Hope Johanna (Martin, 1999:163).

The lyrics to Give me Hope Johanna (Martin, 1999:163).

Among the political turmoil just before the elections in 1994, the minstrels united under the theme of Peace in our Land, symbolized by a badge with two white doves sewn onto their uniforms. The song which became popular the time was that of Give me hope Johanna, a ghoemaliedjie which was about a girl named Johanna and it is said that this song celebrated “miscegenation”, which is appropriate given the context. (Martin, 1999:163). However, most of the troupes were in support of the ANC, which made efforts to improve the organization of the festivals and in so doing also recognizing that it has become part of the culture of the coloured people here. The City Council also allowed the troupes to make use of Green Point Stadium, Hartleyvale Stadium as well as Athlone Stadium, for half of the price they used to pay. The troupes were now also united under the Coon Carnival Development Trust Committee and later in 1996 under the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival Association (Martin, 1999: 165-167).

The Cape Minstrels have a special and long-standing history in Cape Town’s past, and its heritage is still celebrated today. Image source

The Cape Minstrels have a special and long-standing history in Cape Town’s past, and its heritage is still celebrated today. Image source

The post-Apartheid era demonstrated that the Coons had indeed become an important aspect of the identities of the coloured population of Cape Town but also within the popular culture of the city. It also played an important role in the political sphere, making appearances at the meetings and social events of political parties. The Coons as well as Malay and Christmas Choirs continued to appear at official functions in Cape Town. Their presence at the State of the Nation address of President Nelson Mandela and the inauguration of the Mayor of the city in 1998 further emphasizes the fact that they are recognized as an essential part of the culture of Cape Town (Martin, 1999:169-170).

The Penny Pinchers All Stars in 1999 just before the march. The peace doves on the television screen symbolized their support for a peaceful South Africa (Martin, 1999:149).

The Penny Pinchers All Stars in 1999 just before the march. The peace doves on the television screen symbolized their support for a peaceful South Africa (Martin, 1999:149).

The importance of the Coons within South Africa

As one of the longest surviving traditions it has become very evident that the minstrel festival is an important aspect of South Africa’s history and cultural heritage. Cultural heritage can be defined as any part of a community’s past and present, which it deems important enough to be passed on to future generations. It can be tangible such as buildings and it can also be intangible, such as music and dance. It is therefore important to maintain the tradition, which has become so deeply entrenched within the popular culture of Cape Town.

In light of the various ways in which the Apartheid government attempted and failed to destroy the tradition of the minstrels, the fact that the festival still exists today bears testimony to the resilience of the people during the time. The festival also has the potential to become one of the country’s leading tourist attractions. It is maintained that most tourists visiting Cape Town are unaware of the festival. The festival fascinates those who do know to such an extent that many have even participated in the march, in full uniform.

Many in Cape Town were disappointed at the 2015 postponement of the Minstrel carnival Image source

Many in Cape Town were disappointed at the 2015 postponement of the Minstrel carnival Image source

The New Year carnival as we know it today has a long history which dates back to the early years of colonization. Influenced by the American minstrelsy, slaves and former slaves soon established their own form of minstrelsy that has developed into a festival deeply entrenched into the histories of the coloured people of Cape Town to be celebrated for many years to come.

In 2015, the Second New Year carnival was indefinitely postponed due to the fact that the Minstrel association failed to follow the correct application procedures. This brought much disappointment to many in Cape Town who looked forward to celebrating and remembering the history of the event.