Towards Union

It is often assumed that the discovery of gold at the Rand was the chief cause of the South African War. This is not completely true, as British imperialism was chiefly concerned with expanding its territory in Southern Africa, in so doing enforcing dominion over all the inhabitants of annexed territories. The Boer Republics, however, were chiefly concerned by British attempts to annex their self-declared republics, a move that would once again put them at the mercy of capital and politics as dictated by England proper. A further concern was that the Boers were chiefly agriculturalists, with little or no skill in industry and manufacturing, and their conceptualization of their relationship to the land was less utilitarian and more Romantic/Calvinist. Finally, denying the franchise to foreigners in the Boer republics, by their reasoning, was repayment for the treatment the Boers received at the Cape.

The Union Buildings were designed by the British Architect Sir Herbert Baker and inaugurated in 1913. The two wings symbolised the Union of the 'two races' in South Africa: the English speakers and the Afrikaners.

The abortive Jameson raid and the issued ultimatum thereafter assured that a confrontation would occur between the Boer republics and the British colonial machine. Initial confrontations between the Boers and British resulted in a number of victories for the Boers; however, this momentum could not be sustained, because Britain as a superpower had more resources and manpower to realise its expansionist policy. Secondly, with the institution of Kitchener’s scorched earth policy, Boer commandoes were denied any material support. Finally, by arming a large number of Blacks – in addition to employing them as ditch diggers, scouts and logistical support – they ultimately tipped the balance in the direction of the British. Only the realization that, as a population, Europeans were vastly outnumbered by the Black population of South Africa, prevented the British from exterminating the Boers. By this, I mean that the British realised that for racial domination to be viable, they would need to forge an alliance with the Boers – hence the generous terms of the Treaty of Vereeniging.

The result of the South African War was a polarising of South African politics into conservative and liberal streams. This is evident when one examines developments before, during and after South Africa became a Union. These would include the loss of life during the South African War, both in combat and within the internment camps, the tension between the ‘bittereinders’ and the ‘hensoppers’ (those who refused to surrender and those who saw the conflict as futile). A number of issues resulted from the arming of large numbers of ‘blacks’ to fight on both sides of the war. This became a source of tension that made difficult an alliance between a Boer and British. Lastly, an increasing number of educated ‘blacks’ were emerging from the mission education system, and this challenged the notion that ‘blacks’ could be denied the vote because of an inferior educational status.

On 31 May 1902, Representatives of the Boer Republics and the British government signed the Peace of Vereeniging. From the outset of the negotiations, British Prime Minister Chamberlain intimated that Britain would negotiate a peace that fostered unity among the settler populations, with the condition that British culture and loyalty to the crown would be the foundation of this peace. Kitchener went as far as to suggest that the Boers accept the terms of a British peace and tie their hopes for independence to regime change, which would surely, he said, speed up the process. Among the more notable consequences of this treaty was that the Dutch language was granted equal status to English in legislation and that self-rule would eventually be granted to the Union colonies. In order to make this peace acceptable to the Boer republics, it was decided to exclude from the terms an insistence on universal franchise for both Black and White. This would have far-reaching consequences, as Britain in effect abdicated its responsibility to influence the policies and laws enacted by South Africa. During this process, Britain continued the subjugation of traditional African structures of governance through its policies of indirect government.

Black responses to the tug-of-war between the British and the Boer republics

The Bambatha rebellion was a notable Black South African response to the encroachment that resulted from the constitutional tug-of-war between the British and the Boer republics. The root of the Bambata/Bambatha Rebellion was the sustained pressure put by colonial authorities on traditional societies to force indigenous peoples into the European-controlled labour market. Discontent was welling up among many black people in Natal, particularly with regard to the allocation of land for sugar plantations and the heavy tax burdens that the colonial government imposed on blacks in Natal. After Dinizulu was deposed by the Natal government, the traditional way of life of the Zulu people came under renewed pressure, as the colonial administration continued with its policy of subjecting pre-colonial social structures to the colonial purpose. This policy was known as indirect rule.

Among the first indications of a brewing rebellion was the killing of a farmer, Henry Smith, on 17 January 1906 by one of his workers. When questioned during his trail, the worker admitted killing the farmer out of resentment for having to enter in a labour relation with him in order to pay tax. In response to Bambatha’s refusal to pay taxes, the colonial government of Natal sent an armed force to arrest him. Bambatha fled to the Mpanza valley with his family and was given refuge by the Zulu king Dinizulu.

On 14 April 1906, the Natal Government offered a reward of £500 for the capture of Bambatha. On his return to his chieftaincy, Bambatha discovered that the colonial government had installed his uncle as ruler in his place. After deposing his uncle, Bambatha and his followers fled into the Nkandla forests and from there proceeded to wage a guerrilla war against the colonial government. Government measures to suppress this rebellion by Bambatha only served to garner him more support among the Zulu people, and many chieftaincies joined up with him. On 5 May 1906, Bambata’s forces engaged a colonial force dispatched to end the rebellion for good. The colonials, armed with firearms, inflicted heavy losses on Bambatha’s forces. Bambata was forced to flee, but his forces were tracked to the Mome Gorge. In the battle that followed, Bambatha was captured and killed on 10 June 1906.

The response to this rebellion was to set the tone for the constitutional developments that eventually resulted in the Union of South Africa. The status and views of Blacks were considered a secondary concern, as the British were more concerned with encouraging unity and loyalty to England among the settler population. This was played out in the National convention of 1908

National Convention 1908

The most important reason for the National convention of 1908 was to foster closer relations between the four colonies with regard to policies concerning labour, the relationship of between Britain and South Africa, education, fostering equality between Afrikaans/Dutch and English and the question of extending franchise to Black South Africans. This convention can be considered the prelude to South Africa becoming a Union. It is important to note that each of the colonies that participated in this process were considered self-governing territories. Among the major debates at this convention was the question of whether the unification of the South African Colonies would take on the form of a union or a federation. What the shape of the South African economy would take and legislative procedures that would be followed to empower laws were also debated. The final concern was the apportioning of constitutional authority in such a way as to avoid a situation in which the political interests of one group would dominates the other. This convention in many regards constituted the foundation for the Union of South Africa, as many of the issues discussed and examined would form part of the laws of the eventual Union.

South Africa Act 1909 and the denial of franchise to Black South Africans

The South Africa Act of 1909 could be considered as an empowering of the decisions reached at the National Convention of 1908 by the British Parliament. This is to say that draft laws, such as language policy and the denial of the franchise to Black South Africans, as well as the eventual form the Union of South Africa were now finalised. The passing of this act, however, was not made without opposition as the South African delegation – known as the Schreiner mission – travelled to Britain in order to convince the English parliament of the need to make amendments to the South Africa Act, specifically to confer the right to vote upon all South Africans. Included in this delegation were Dr Abdurahman, as leader of the ‘Coloured’ delegation, and JT Jabavu, as leader of the ‘African’ deputation. The main concern of the Schreiner mission was that the unification of the colonies would empower the Union parliament to remove the franchise from persons of colour at the Cape.

Britain, as indicated earlier, had at this point given up on influencing governance in South Africa as long as South Africa remained loyal. The granting of self-governance to the different South African colonies as well as marked encouragement toward closer economic ties brought the vision of a unified South Africa closer to reality. In 1909, Lord Elgin, the British Colonial secretary, met with the leaders of the different colonies in South Africa and discussed the issue of a potential union as well as a proposed constitution for the Union of South Africa. Old divisions hampered this process though, as the smaller and less wealthy colonies feared that the larger and wealthier ones would dominate them. The Cape colony, in particular, feared that in a union, the other colonies would eliminate Black voters from the voters’ roll, and these voters were the electoral base for many Cape politicians.

Natal, on the other hand, wished to retain some of its independence, but eventually relented on this condition. When it came to actually forming the Union, an important concern was who would lead the government. Initially Steyn, who was once president of the Orange Free State, was asked to form a government, but he declined the offer, while Merriman, as last prime minister of the Cape Colony, indicated he would never serve under Louis Botha. Thus, it was decided that Botha would form the first government as Prime Minister.

Launch of Union 1910

On the 31 May 1910, exactly eight years after the Boers had made peace with the English through the Treaty of Vereeniging, South Africa became a Union. Despite the mistrust in the Boer camp, the Afrikaners, as they now became known, had negotiated and achieved self-determination.

Politically, it was nothing short of a miracle that the British and Afrikaners were able to unite to form the Union of South Africa despite the hatred, tensions and damage that the two South African Wars had inflicted on the psyche and landscape of the country. It must be admitted that the formation of the Union was a direct result of the Treaty of Vereenging. By ignoring the wishes of the majority of the population, the formation of the Union of South Africa contributed to the political upheaval and turmoil that would engulf the country for the next eighty years.

Black response to the formation of the Union

The response of the African press to the formation of Union was one of undisguised hostility. Much effort was directed at stalling or changing the draft Act of the South African Union. But despite all efforts, the act was passed through the colonial parliaments.

In response, John Tengu Jabavu convened the Cape Native Convention. Jabavu was an important Black political leader, educationist and journalist, and he played an important role in the establishment of what was to become the African National Congress. The principle objection of this convention was that Britain would no longer be able to intervene on behalf of the native people and that the relationship between them and the Crown would be broken.

The attempt was doomed to fail, despite the fact that every politically conscious black person was against the terms and not the principal of the Union. The representatives of the National Convention and various colonial governments gave their support to the formation of the Union under terms that virtually ignored the Black population. Despite vocal objections to the terms, the establishment of the Union of South Africa went ahead.

The Formation of the ANC 1912

Preliminary drafts of the Union governments Natives’ Land Act were debated in 1911 and the Mines and Works Act was passed in 1911. These laws and the formation of the Union were important factors leading to the formation of the South African Native National Congress on 8 January, 1912, in Bloemfontein, renamed the African National Congress in 1923. Land dispossession lies at the heart of South Africa’s history and heritage of inequity. The new ANC was created against the backdrop of massive deprivation of Africans’ right to own land.

To read more about the formation African National Congress in 1912 and the factors leading to the formation.

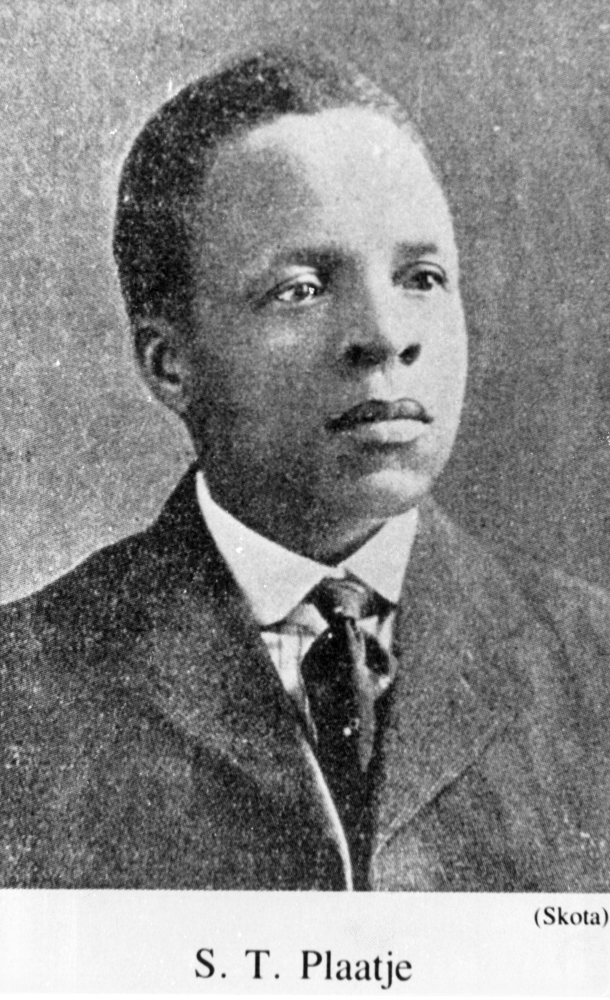

Sol Plaatje. Source: South African tourism1913 Natives’ Land Act

Sol Plaatje. Source: South African tourism1913 Natives’ Land Act

Although the Colonial Government passed many discriminatory laws against Blacks, the most severe, the 1913 Natives’ Land Act, codified those injustices by preserving the large majority of the Union’s land for the exclusive use of the white minority. The Act effectively meant that access to land and other resources depended upon a person’s racial classification. This legislation caused endemic overcrowding, extreme pressure on the land, and poverty.

Activity

– There is a lot of information on the SAHO website about this act. Using the websites search function, try to consolidate all these bits of information and write one page on how the native land act impacted on Black families at the time.

– Secondly, search the SAHO website for Sol Plaatje. Who was he, and what role did he play at this time in history?