The sinking of the SS Mendi was caused by the reckless action of the captain of the SS Darro. It remains the greatest wartime maritime disaster ever suffered in South Africa. During the First World War, there was a shortage of labourers, which despite the draft, caused delays in moving supplies from the rear to the front lines. In September of 1916, General Louis Botha, the current Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa at that time, informed Parliament that Britain had requested that the South African Native Labour Contingent provide 10 000 men to work behind the front lines in France.

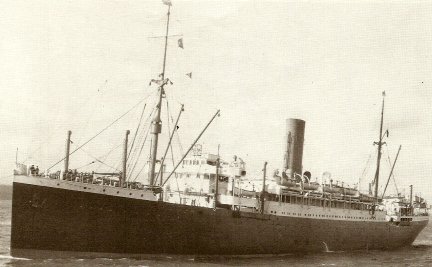

The Mendi was built in Glasgow and in 1905 registered to the British & African Steam Navigation Co Ltd. She is shown here in pre-war days in use as a mail ship. Image courtesy of the John Gribble Collection Image source

The Mendi was built in Glasgow and in 1905 registered to the British & African Steam Navigation Co Ltd. She is shown here in pre-war days in use as a mail ship. Image courtesy of the John Gribble Collection Image source

Their first task was to act as dock workers and to unpack the incoming supplies and then move further inland to support the troops. This proposal was quickly approved despite lingering resentment among the Afrikaner representatives towards the British over actions during the Anglo-Boer Wars. While in certain areas of the country such as Lovedale, Healdtown and Blythswood, many Blacks were willing to volunteer; in others, there was less enthusiasm as people felt they should have been asked to volunteer as fighters and not as labourers.

Diving the SS Mendi © Martin Davies Image source

Diving the SS Mendi © Martin Davies Image source

The concept of training and arming a Black army was considered undesirable by the White government as many felt they could return to South Africa and lead an armed insurrection. In the end, thousands volunteered and many arrived in the conflict areas. They provided valuable support to the British war effort. Most of those on the SS Mendi unfortunately never reached their destination. Leaving Plymouth harbour on 20 February 1917 during the late evening, she sailed towards La Havre, France.

SS Daro Image source

SS Daro Image source

Wartime ships ran dark or with low lights and with inclement weather her visibility was greatly reduced. It was at 5.00 am on 21 February 1917 that the SS Darro, a far larger ship, which was not only running with low lights but not blowing her horn to alert others to her presence, and at full speed hit the SS Mendi straight down on the starboard side of the ship. The initial collision killed many. A number of the lifeboats were rendered unusable due to the speed at which she heeled over. The ship began to sink. The SS Darro did not pause to assist but rather continued onward. This action would see Captain Stump of the SS Darro to in an investigation and having his license suspended for a year.

The men on the SS Mendi were have been said to be surprisingly calm when considering the watery fate that faced them, despite that a large part had never seen the ocean prior to this journey and an even greater number had never learnt to swim.

According to witnesses from the disaster, the men acted with such dignity and calm that several of the crew gave up their places on the few lifeboats to the Black volunteers. There was even an anecdote that a small group encircled their White NCO and did a war dance around him until the waves came crashing down. As heartening as that image is, it is extremely unlikely to have happened as there is not a proven witness or survivor mentioned of it. Rather this tale first appears in a book, J.S.M Simpson's South African Fights (London, 1941). While this may have not occurred, the final sermon by Isaac Williams Wauchope, an interpreter and minister is not disputed.

Black privates standing at their last parade before boarding the SS Mendi Image source

Black privates standing at their last parade before boarding the SS Mendi Image source

"Be quiet and calm, my countrymen. What is happening now is what you came to do...you are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers...Swazis, Pondos, Basotho...so let us die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war-cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies."

These words calmed the men on the doomed ship and provided inspiration for unity between people since. The men of the SS Mendi, Black and White, faced death together.

George V, centre, inspecting the South African Native Labour Corps at Abbeville, France, July 1917 © National Library of Scotland Image source

George V, centre, inspecting the South African Native Labour Corps at Abbeville, France, July 1917 © National Library of Scotland Image source