The student protest that broke out on 16 June 1976 was organised and directed by the Soweto Students Representative Council (SSRC). Recent accounts of the event suggest that the SSRC was motivated and guided by underground networks of the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). This has been confirmed by some student leaders who were actively involved in organizing the event. Other student leaders were critical of the ANC and PAC, arguing that the two organisations had become alienated from developments in South Africa since the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.

In exile the latter group, led by Tsietsi Mashinini and Khotso Seatlholo, sought to transform the SSRC into a national liberation movement distinct from and autonomous of the ANC and PAC. This was realised with the formal launch of the South African Youth Revolutionary Council (SAYRCO) in the Zambian capital, Lusaka, in April 1979. The launch marked the end of nearly three years of planning and organisation, beginning in August 1976 in Botswana. Botswana became the epicentre of SAYRCO’s brief existence, though it did establish a branch in Lesotho and had representatives in Nigeria, London and Bonn in West Germany.

On 2 August 1976 the SSRC was formally launched with Mashinini as president. Other members included representatives from the five high schools in Soweto. They included Majakathata Mokwena from Orlando High School, Seatlholo and Issy Gxuluwe from Naledi High School, Murphy Morobe from Morris Isaacson High School, and Abiel Lebelo from Madibane High School. Emerging Junior Secondary Schools directly affected by the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction were also represented, among them Seth Mazibuko of Orlando West Junior Secondary School.

Immediately after its launch the SSRC decided on a workers’ stay away two days later, on 4 August 1976. On the same day, students were called upon to march to John Vorster Square Police Station to demand the release of political detainees. The workers’ response was overwhelming. It was reported that nearly 70 % of the workers heeded the call to stay away from work, with schools deserted as students gathered at different points to march to John Voster Square.

Students attempted to march from different points in Soweto to John Vorster Square Police Station. One group of students was stopped by a police cordon outside New Canada Station, and another on the edge of the Soweto Highway. While the first group dispersed without incident, clashes erupted between police and the second group near the highway. Police opened fire, using live ammunition, while students retaliated by throwing stones. Madibane High School representative and executive member of the SSRC Abiel Lebelo was shot and killed. By the end of the day scores of protesters had been killed and many more injured.

As clashes between police and residents became routine for the remainder of August, the hunt for members of the SSRC intensified, with police offering a R500 reward for information that would lead to Mashinini’s arrest. At the end of August Mashinini fled to Botswana and was succeeded by Seatlholo. At about the same time scores, probably hundreds of students also fled to neighbouring states seeking political asylum. Those from Soweto were joined by students from Alexandra, north of Johannesburg, and Tembisa on the East Rand, where the unrest had spread. The number of students fleeing the country increased significantly as the unrest spread to boarding schools in rural areas and homeland territories

Unlike the march on 16 June, which some historians have characterised as largely spontaneous, the stay away in August was the result of prior planning by the SSRC. Sometime in July representatives who had called for the march in June met for several days at Wilgespruit, west of Johannesburg, for a series of seminars on a range of topics. The seminars were organised by the Wlgespruit Fellowship Centre. Among the speakers – with many addressing the ongoing unrest in Soweto – was Percy Qoboza, editor of the World.

Most of the students fleeing the country went to Botswana. The next preferred destination was Lesotho, with Swaziland considered the least attractive. In fact, the majority of students who sought political asylum in Swaziland entered the country under the pretext of attending a music concert. Bob Marley was scheduled to perform in Swaziland in December 1976. Consequently, thousands of South Africans headed for Swaziland, along with those intending to remain there as exiles.

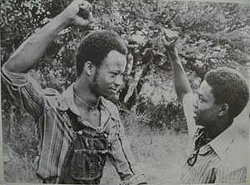

Tsietsi Tsietsi Mashinini and Khotso Seathlolo, Gaborone, 1977. Source: www.oumarou.net/ [accessed 23 May 2012]

Tsietsi Tsietsi Mashinini and Khotso Seathlolo, Gaborone, 1977. Source: www.oumarou.net/ [accessed 23 May 2012]

In Botswana, exiled students were solicited by the ANC and the PAC. Many joined the ANC and were later sent to Angola and then to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union for military training. It is often argued that among those that joined the ANC, many were underground operatives of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) inside South Africa before going to exile and becoming the first group of recruits in the June 16 detachment.

Mashinini tried to draw large numbers of students to Botswana to the informal structure that would become SAYRCO. He was convinced that, for exiled students, joining the ANC or the PAC was not an option that would advance the liberation struggle in South Africa. In an exclusive interview with former Weekend World journalist Duma Ndlovu, Mashinini declared that the ANC was defunct and the PAC dead. He urged students leaving South Africa not join the ANC or PAC. This marked the beginning of several attempts to establish a student formation in exile.

Seatlholo became president of the SSRC from the end of August 1976 through to the end of the year. His immediate challenge was to keep up the momentum and organise further campaigns to undermine the apartheid government’s authority. He began by addressing mass meetings at high schools in Soweto, appealing to those intending to go into exile not to join the ANC or PAC. Between June and December 1976, some students heeded Mashinini’s call. Prior to the conference in Lusaka, informal structures at various stages of development existed in Lesotho, Botswana, Swaziland and Nigeria. Between August 1976 and April 1979 these isolated structures operated independently of each other, united only by the conviction that they would join neither the ANC nor the PAC.

Seatlholo called for another student march into Johannesburg on 22 September 1976. The march was largely successful, with thousands converging at the Johannesburg Station to march to John Vorster Square. Police intervened, arresting scores of students and dispersing the rest. Thousands of students returned to Soweto triumphant, emboldened by the fact that they had succeeded in getting to the city centre. The event marked the end of schooling for the rest of 1976. In the meantime, the police hunt for Seatlholo intensified. After two months of evading arrest, Seatlholo fled to Swaziland some time in November or early in December. Finding it difficult to organise and establish a student formation in Swaziland, he went to Botswana sometime in 1977.

In Botswana, Mashinini continued to recruit students arriving from South Africa to join the informal structure he led. He undertook speaking tours during 1977, addressing students at universities in the US in an attempt to garner support for the student movement he planned to establish. In 1978 Mashinini travelled to West Africa and met with Sekou Toure and William Tolbert, presidents of Guinea and Liberia respectively. Both heads of state pledged their support for SAYRCO.

In Nigeria Mashinini was warmly received. At the time General Obasanjo was head of state having seized power in a coup earlier in the decade. Obasanje offered material support to the organization while he remained at the helm of the Nigerian government. An exiled student and member of the SSRC Comfort Molokoane was sent as a students’ representative in West Africa and was based in Lagos.

Towards the end of 1978 and early in 1979, Mashinini was interviewed by the South African-based PACE Magazine He told PACE sub editor Lucas Molete that students were establishing a political formation aligned to neither the ANC or PAC and capable of advancing the liberation struggle. He also revealed that he was engaged to Wilma Campbell, the Liberian model he had met at Mirriam Makeba’s house. The informal structure in Botswana, now led by Seatlholo, decided to suspend Mashinini pending ratification by the fledgling movement. Seatlholo took charge of preparations for the launch of the movement. The main reason for Seatlholo’s suspension was the discovery that PACE Magazine was a publication of the Department of Information under Minister Connie Mulder. (See box for a brief account of the Information Scandal

In 1974 the apartheid government under BJ Vorster established the Department of Information with a slush fund amounting to R64m from the Defence budget. The Department’s brief was to spread propaganda on the virtues of apartheid. PACE Magazine was the South African publication established solely for this purpose. When the link between PACE and the Info Scandal became known, Mashinini was in danger of being discredited. For this reason, the decision was taken by the group in Botswana to suspend him.

In Lesotho there were no high profile SSRC members who could attract significant numbers of exiled students. The few that were there were isolated, waiting for a break that could lead to the establishment of a recognisable structure and establishing contact with those in Botswana and elsewhere. By the beginning of 1978, there were less than ten members based in Qoaling, a village just outside Maseru. They were in regular contact with Father Aelred Stubbs in Quthing, and talked of establishing a formal structure.

Before such a structure could be formed, the entire group, along with student exiles who had joined the ANC, were offered scholarships by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to study in West Germany. Because the majority were high school students when they left South Africa and had not yet matriculated, they were enrolled for vocational courses like carpentry, bricklaying and electronics. For many, the opportunity to leave landlocked Lesotho was irresistible.

At the end of October 1978, nearly all student exiles arriving in Lesotho after the Soweto uprising had taken up the UNHCR scholarship and moved to West Germany. They were joined by others from Botswana and a handful from Swaziland. The Quthing group, for a while, teamed up with those from Botswana in an attempt to revive the exiled student formation. This group, however, was not represented at the founding conference, probably because it fell apart.

In the meantime, developments inside South Africa gave impetus to the establishment of a student formation in Lesotho. Seatlholo was succeeded by Sechaba Montsitsi as president of the SSRC at the end of 1976. Montsitsi, unlike Seatlhlo, seemed more inclined towards establishing links with the ANC than promoting the idea of an autonomous student formation. He also opened a dialogue with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a move heavily criticised by political formations affiliated to the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

In June 1977, shortly before the first anniversary of the Soweto uprising, Montsitsi, along with the entire executive committees of the SSRC and NUSAS, was arrested in a house in Diepkloof, Soweto. NUSAS members arrested with them included Max Price, current vice chancellor of the University of Cape Town, and Peter De Villiers, who was president at the time. While in detention, Montsitsi was succeeded by Trofomo Sono as president of the SSRC. Sono remained president until October 1977 when the SSRC was banned along with all BCM formations. Sono too fled in October and joined the PAC in exile. He returned years later as a member of the Azanian People’s Army (APLA).

When schools reopened in Soweto in 1978, the Soweto Students League (SSL) was formed to continue the programmes of the SSRC. Its president was Oupa Mlangeni, and Teboho Moremi was appointed secretary. Not much is known about the other members of the SSL. The SSL immediately established regular contact with Lybon Mabasa and Ishmael Mkhabela, both of the Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), thus locating itself within the BCM tradition. But it was short-lived attempt, with police more determined to avert a repeat of the events of June 1976. Mlangeni and Moremi soon went into hiding in Bloemfontein, where they helped establish the Bloemfontein Students League (BSL).

A riot involving students in Bloemfontein’s black townships broke out during September and October 1978. The attention of the police turned to Bloemfontein, and it was discovered that Mlangeni and Moremi were behind the outbreak of unrest in the town. The police search for the duo escalated and they were forced to flee to Lesotho, arriving just after almost of the exiled students based in Qoaling had departed for Germany. The duo teamed up with students who had declined the UNHCR scholarships and revived an exiled student formation in Lesotho.

Shortly after Mlangeni and Moremi arrived in Lesotho, they were joined by about a hundred students fleeing police harassment in Bloemfontein. The latter were members of BSL and teamed up with Mlangeni and the Qoaling group. Between October and December 1978 the Qoaling group grew significantly, benefiting from the arrival of students from Bloemfontein and other parts of the Free State. All this happened at the time when the entire ANC membership of exiled students had left Lesotho for West Germany.

Contact between the interim structures in Lesotho and Botswana was finally made in February 1979. Seatlholo’s group sent a representative, Lefa Moffat, to visit the Qoaling group in Lesotho to discuss the launching conference scheduled for the Easter weekend of 1979. Moffat spent a week in Lesotho before returning to Botswana. A few days before the Easter weekend, a representative from Botswana arrived with two tickets for members of the Lesotho delegation to the conference starting in Lusaka over that weekend. But Lesotho authorities refused to issue passports to the delegates.

The representative from Botswana remained in Lesotho and presided over the formation of the structure and election of a committee. Mlangeni was elected president of the Lesotho branch with Steve Lebelo was appointed secretary. Other executive committee members included Moremi and Luyanda Msumza, who was initially linked to the PAC. When the conference ended Mokoena was sent to Lesotho to report back to the Qoaling group. He was joined by delegates from Swaziland who, fearing arrest and deportation to South Africa if they returned, opted to head to Lesotho to seek political asylum. Margaret Moshoeshoe, a man named Shabaz and a woman known only as Thami joined Mokoena, arriving in Lesotho after the Easter weekend.

Mokoena was arrested soon after landing at the Lesotho International Airport. Traveling on a passport issued by the UNHCR, he was also in possession of another issued by the Lesotho High Commission in London, where has was based before he attended the conference in Lusaka. Mokoena’s grandfather was a Lesotho national and this qualified him for a citizenship and a passport. At the time the Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA) had stepped up its bombing campaign against Leabua Jonathan’s government. Lesotho’s security police suspected Mokoena of being an LLA operative, and detained him for several weeks before he was cleared of all suspicion.

Early in May, Mokoena was released from detention. Soon thereafter SAYRCO in Lesotho began organising the third anniversary of the June 16 uprising. In Lesotho the first two commemoration services in 1977 and 1978 were organised by the ANC. In exile politics at the time and in Lesotho in particular, the June 16 commemoration was contested terrain. The event always generated heated discussions about “ownership”, with the ANC asserting that its underground structures had inspired and given direction to students during the uprising. This version of events was contested by SAYRCO members, who proceeded to organise the commemoration service.

During the month leading up to 16 June 1979, two parallel services were being organised: one by SAYRCO and another by a student group based at the National University of Lesotho. The latter group was made up of students from South Africa (not exiles), Zimbabwe and South West Africa (now Namibia who were aligned to the ANC, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) and the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO). Eventually this group outmanoeuvered SAYRCO and organised the commemoration of the Soweto uprising in Lesotho in 1979.

Speakers drawn from the ANC, ZAPU and SWAPO condemned what they perceived as a divisive “third force” in the liberation struggle. SAYRCO’s programme, which in the event was not used, had included representatives from Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), the PAC and a group aligned to the ANC 10 (or ANC of Azania). This was a splinter group of the ANC that first emerged in Zambia in 1978 and spread to Lesotho by the beginning of 1979.

Being upstaged by the ANC and its allies, SAYRCO was dealt a devastating blow. In the weeks and months following this event, internal squabbles surfaced within SAYRCO. There were complaints about the leadership, in particular Mokoena, who was seconded by SAYRCO’s National Executive Committee (NEC) at the end of the conference in Zambia. Shortly thereafter, Mokoena returned to England. Interest in SAYRCO dwindled as members, made up mainly of the Bloemfontein contingent involved with BSL and a few new arrivals from the Vaal townships, left to join the ANC. This marked the beginning of the end for SAYRCO in Lesotho, and by the end of 1979 it had ceased to exist. The spotlight swung back to Botswana.

During 1980 Seatlholo continued to organise events for SAYRCO. In mid-1980 he traveled to Lesotho in the hope of finding comrades to help revive the structure. He found there were no prospects for reviving SAYRCO in Lesotho and returned to Botswana.

In December a Youth Guild of the Methodist Church in Diepkloof, Soweto, arrived in Botswana for a summer camp. Seatlholo made contact with them and arranged to travel to South Africa early in 1981 in the hope of establishing underground structures and ferreting students to Botswana and grow SAYRCO.

Seatlholo secretly entered South Africa early in March 1981. His visit coincided with the 10- days school holiday in March. A day after he arrived he was arrested at a house in Diepkloof and charged with sedition. He was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison. He was released as part of the negotiations for a transition to democracy. His imprisonment marked the final demise of SAYRCO.

Conclusion

The history of the Soweto uprising of 16 June 1976 has always generated controversy about whether or not it was the outcome of ANC and PAC underground operations. A great deal of the literature ignores developments in exile which reveal the resilience and longevity of a student formation existing independently of the ANC and PAC.