Early History

Few Southern African indigenous groups have so captured the interest of the world as have the South amaNdebele of the central highveld, an area previously known as the Transvaal but today incorporated into the Gauteng and Northern Provinces. Their highly colourful and intricately painted homesteads, their skilled and varied beadwork, their clear language of architecture, and their stately forms of dress have made them a popular field of research with artists, architects and social anthropologists. They have also become a major focus of interest for many visitors to this country.

It is generally accepted today that the South Ndebele migrated onto the central highveld of southern Africa some four centuries ago. The exact date of their arrival is difficult to determine, but estimates tend to vary from 1485 by Fourie, through to the 1630-1670 period established by Van Warmelo. The latter dating is today regarded as the more reliable of the two.

Both Fourie and Van Warmelo are in agreement that, despite the fact that the Ndebele settled in a predominantly Sotho-Tswana speaking area, they have retained their customs and Nguni language roots with "remarkable tenacity". However some researchers have suggested a Sotho influence in some rituals and aspects of material culture, and more recent research into their architecture, settlement patterns, and methods of construction seem to indicate a definite Pedi-Tswana influence, even allowing for the adaptations one has come to expect of a culture moving from the grass-rich coastal lands east of the Drakensberge to the more extreme thermal variations found on the South African Highveld.

Details regarding the Ndebele prior to their arrival on the highveld are scarce, and their recorded history only begins with the names of their first two kings, Mafana and Mhlanga. Following Mhlanga's death the clan became embroiled in a protracted struggle which eventually brought his son, Musi, to the leadership. By that stage the group had already moved to Mnyamana, near Wonderboompoort, immediately north of the future Boer town of Pretoria. Musi, in his turn, had five sons: Manala, Masombuka, Ndzundza, Mathombeni and Dhlomu. Upon his death Musi was buried beneath a tree at Wonderboompoort, a location which is still visited by his descendants to the present day. Almost inevitably his sons quarreled over their inheritance and, as a result, the clan split into a number of smaller groups, the largest two coalescing under the leaderships of Manala and Ndzundza respectively. Masombuka left briefly but rejoined Manala later on, while Dhlomu and some of his followers are reputed to have returned to KwaZulu. For the purpose of subsequent Ndebele history the Manala were held to be the senior of the two groups.

In due course Ndzundza was succeeded by his son Mxetsha who, in his turn, was succeeded by his son Magoboli. Magoboli was followed by his son Bongwe, who unfortunately only reigned for three years, and as a result of his premature death, his brother Sindeni was appointed as regent. At this time, for reasons that are not known, there was a shift in the line of succession, which allowed Sindeni's son, Mahlangu, to follow his father. As a result the ruling family, which had previously been known as the Mdungwa, now became the Mahlangu. The last of these events probably took place in the latter part of the mid-eighteenth century.

Mahlangu was succeeded by his son Phaswana, who was followed in his turn by Maridili, who was followed in rapid order by his four sons, Mdalanyana, Mgwezana, Dzele and Mxabule. The last, Mxabule, was murdered by his nephew Magodongo, the son of his older brother Mgwezana, who then became head of the Ndzundza. In 1823 the amaKumalo under Mzilikazi invaded the highveld, and in about 1825 they attacked the Ndzundza, burning their capital at Mnyamana, and killing Magodongo together with all his sons from his Right-hand House. The remnants of the Ndzundza fled from Mnyamana under the leadership of Mabhogo, a younger son of Magodongo and the only survivor of his Left-hand House, and settled at Namashaxelo, near the site of the latter-day Boer village of Roossenekal. At this time Mabhogo, who ruled until 1865, entered into an alliance with the neighbouring Pedi chief Malewa, and it seems probable that the alterations in Ndebele material culture can be dated from this time onwards.

In 1847 Mabhogo was visited for the first time by groups of disaffected Dutch farmers from the Cape, better known as Voortrekkers, who rapidly came to know the Ndebele as either the Mapog, Mapogga, Mapoers, Mapoch or M'pogga. Although most Ndebele today find this form of address derogatory, many South Africans sadly still persist with this form of address.

Almost from the onset sporadic skirmishes began to take place between these new immigrants, or Boers as they became known, and the Ndebele-Pedi alliance, who actively resisted the incursions which they were beginning to make upon their ancestral lands. In 1864 the alliance was attacked, and defeated, by a Swazi force acting at the instigation of the Boers, leaving the Dutch in the rear-guard to conduct a simple mopping-up operation of survivors. Soon thereafter, in 1865, Mabhogo died, leaving the Ndebele to sort out a complex and bitter inheritance struggle. As a result Ndebele leadership passed to the Masilela family. Soqaleni ruled until 1873, followed by Xobongo, a tyrant who ruled until 1879, when he was succeeded by Nyabele.

Origins of the name “Ndebele”

The name, Ndebele, was probably derived from the Sotho-Tswana term "tebele", meaning a stranger, or one who plunders. They share in this appellation with at least three other South African groups, the most famous being the amaKumalo, an Nguni-speaking group who, under the leadership of Mzilikazi, migrated from northern KwaZulu in 1823, and after a residence of some thirteen years on the highveld, moved to western Zimbabwe in 1837, where they became know by the Shona variant of Matabele. The name has also been applied to the North Ndebele, originally a Venda-speaking group who settled in the Pietersburg area and became acculturised by their Sotho-speaking neighbours; and the baTlokwa, a Sotho-speaking group who joined the British invasion of KwaZulu in 1879, and in consequence were awarded land in the Nqutu region of KwaZulu-Natal. The term is therefore consistent with the idea of being a stranger, an invader, or perhaps even a refugee into a region.

A brief history of polygamy in Southern Africa

One of the preconceptions more popularly held by both academics and lay public alike in regard to southern African rural society is that the indigenous family unit is polygamous in nature. This is only partly true. A broad survey of homestead patterns in the region reveals that whilst a number of polygamous settlements may still be found in the rural countryside, these are in a distinct minority, and monogamous marriages appear to be the general norm. It could of course be argued that this is a recent development brought about by the work of Christian missionaries, but the validity of such an assumption needs be questioned. Not only do the Christian churches which enjoy the largest following in southern Africa, the so-called Independent Churches, permit their followers to practice polygamy, but although the practice of polygamy was indeed more prevalent during the last century, its presence was not as widespread as various missionaries way have wished us to believe. Lichtenstein wrote of the Xhosa in 1812 that:

"Most of the Koossas have but one wife; the kings and chiefs of the kraals only have four or five."

This was reinforced by Alberti who stated, also of the Xhosa, that:

“Those with least resources, must be satisfied with one woman, others have two, and rarely more.”

Contemporary visitors to other parts of the country have come to similar conclusions. Livingstone went one step further and in 1857 estimated that approximately 43% of Tswana men practiced polygamy, and then only a very small minority of these had more than three wives. By 1946 an official census revealed that this figure had dropped to 11% with only 1.3% having three wives or more.

The practice of polygamy may, in most cases, be explained in terms of a levirate, a social practice, used to ensure the continued status and survival of widows and orphans within an established family structure. While it is true, therefore, that every rural family is potentially polygamous in nature, we need to question whether such polygamy was the result of "male sexuality and lust", as the missionaries would have it, or merely the enforcement of social obligations intended to reinforce ties between family or clan groupings. Recent data would seem to show that some 27% of rural households are currently headed by widowed or single women. If we were to assume that in the 1850s an equivalent number of women could have become widows and were thus absorbed into the monogamous households of family members, thus making them polygamous, then it will be seen that this form of union could have accounted for most of the polygamous marriages recorded by Livingstone among the Tswana. The remaining group, those with three wives or more, were a distinct minority and their polygamy may be explained in terms of group leaders creating political alliances and gaining control of resources for their own communities.

The general trend away from polygamous unions evidenced since 1900 could therefore be explained in two ways. The growth of urbanisation and the establishment of urban-based political structures has brought about a decreased emphasis upon both regional group identity and the power of the traditional and inherited rural leadership. The need for making unions based upon political expediency has thus lessened considerably. The economics of obtaining a bride in the rural areas has also changed substantially over the past five generations, as women also began to enter the ranks of an industrialised and urban proletariat in increasing numbers after the 1930s.

The conclusion therefore is that the practice of polygamy may have been common in southern Africa up to the end of the last century but that it was never as widespread as has been popularly represented.

The ZAR war against the Ndzundza Ndebele

The leadership of Nyabele was to mark the final era of Ndzundza Ndebele independence. On 13 August 1882 the Pedi paramount chief Sekhukhune was killed, together with fourteen of his advisors. The assassins were acting at the behest of Mampuru, Sehukhune's half brother, who had previously contested the Pedi chieftainship in 1861, and who, under the British administration of the Transvaal, had acted as chief during Sekhukhune's imprisonment in Pretoria from 1879 to 1881.

The ZAR Government, conscious of its newly-won independence from the British, was determine to exercise its authority over the Pedi and demanded that Mampuru be handed over for trial. Mampuru then fled and sought refuge with the Ndzundza, who had previously supported him in 1861 in his claim for the Pedi leadership. The Volksraad of the ZAR demanded his apprehension, but Nyabele not only declined to hand over Mampuru, but also refused to pay the customary Hut Tax to the new Transvaal government. Although largely symbolic, this gesture was also an open act of defiance which proclaimed Ndzundza independence from the ZAR and refuted Boer claims of suzerainty over his people.

Given their precarious hold over their indigenous subjects, this was not a challenge which the newly established ZAR could afford to ignore, Consequently on 30 October 1882 a burgher commando under the leadership of Gen Piet Joubert set out from Middelburg and invested the Ndzundza mountain stronghold near Namashaxelo. In reality this was little more than a series of caves where Nyabele and his people had thought of making a tactical retreat. No records exist of the exact number of Boers engaged in this campaign but, judging from General Joubert's letters, it appears that no more than 1000 to 2000 men were ever in the field at any one time. Certainly the Boers do not appear to have had much stomach for the fight, leading Joubert to complain to the Volksraad that the burghers "seemed to prefer looting cattle for their own account". After a long campaign of nearly nine months, the Ndzundza, starved and dynamited into submission, capitulated and handed Mampuru, bound hand and foot, over to the Boers. Both Mampuru and Nyabele were taken prisoner to Pretoria where they were tried for insurrection and sentenced to death. The British, who had previously supported Mampuru's claims to the Pedi leadership, attempted to intercede on their behalf with the ZAR, but their efforts were only partially successful, for while Nyabele's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, Mampuru was hanged in Pretoria Prison on 22 November 1883.

At the same time the Volksraad declared the Ndzundza ancestral lands to be forfeit to the ZAR Government, which then proceeded to parcel them out to members of Joubert's commando. The surviving Ndzundza were indentured for five years as labourers to the farmers in the district, thus effectively scattering them and breaking their power as a tribe forever.

In retrospect the ZAR Government might appear to have acted in a somewhat precipitous manner in what was, after all, an internecine squabble which did not present them with an immediate threat. However, for the ZAR the question of Pedi succession was a sensitive one which needs to be read in conjunction with political conditions prevailing in the Transvaal at the time. Since the establishment of the Transvaal Republic in 1852, the region had remained in an almost constant state of anarchy. The wars against the Tswana in 1852 and 1858, and against Makapane in 1854; the rise of separate Boer republics at Utrecht (1854), Lydenburg (1856), and Zoutpansberg (1857); the establishment of a Boer revolutionary government in the Waterberg in 1860 and the four years of civil war which followed it; the Swazi attack upon the Ndebele, instigated by the Boers in 1864; the war against the Venda, the Boer retreat from the Zoutpansberg and the destruction of Schoemansdal by the Venda in 1867; and the disastrous war upon the Pedi in 1877, all depleted its resources, and by the time the British annexed the Transvaal on 12 April 1877 its government was bankrupt and on the point of collapse. Boer independence from British rule was only regained after a brief series of battles in 1881, and thus it was to be expected that any challenge made against the newly-established government of the ZAR would be met with harsh and immediate force. The newly-elected Volksraad must have been understandably anxious to avoid a return to conditions prevailing in the Transvaal five years previously while, at the same time, serving notice to British and Black alike that it was determined to maintain the independence it had regained only the previous year.

Msiza settlement at Hartbeesfontein

During the years of Nyabele's imprisonment, some of his family and personal advisers were allowed to settle on the white-owned farm of Hartbeesfontein, located between Wonderboom and Derdepoort north of Pretoria, in order to be near him. These were lands previously occupied by the Ndebele prior to their move to Namashaxelo, but which had since been annexed by the Transvaal government for white occupation. Shortly before the outbreak of the South African War of 1899-1902 Nyabele was granted a pardon. However he was not allowed to return to Namashaxelo but rejoined his followers at Hartbeesfontein where he is believed to have died in about 1903.

He was succeeded by Mfene, the second son of his eldest brother Soqaleni, who had preceded Nyabele as chief of the Ndzundza. Mfene is reported to have lived at Hartbeestfontein for a few years before moving with the bulk of his family and followers to a site on the upper reaches of the Wilge River, known as Weltevrede, near Vaalfontein. Mfene was followed by his son Maysha and, when he died in about 1951, he was succeeded by Mabusa David Mahlangu who continues to reside at Weltevrede.

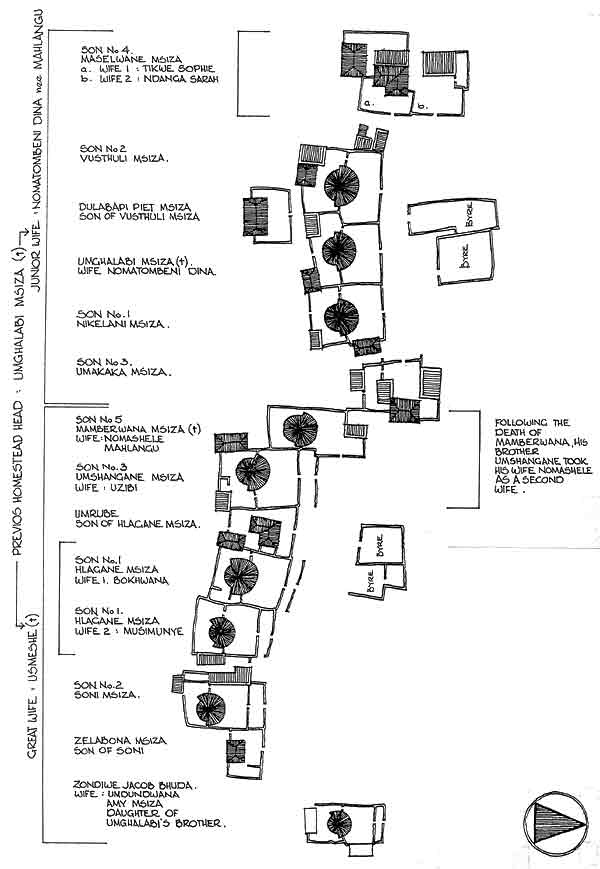

The contingent of Nyabele's immediate family and followers included Kgalabi (also given as Umghalabi) Msiza whose family, the Msiza, traditionally enjoyed the high status of "shield-bearers to the Ndzundza king". He settled at Hartbeesfontein where, in time, he became the patriarch of a substantial extended family. His first wife, Usmeshe, raised a family which included six sons, while his second, Nomatombeni Dina Mahlangu, bore him another five. The number of daughters in the family is not known. Nomatombeni was the daughter of Nyabele and his wife Sibiya, and probably met and married Kgalabi at Hartbeesfontein.

When Mfene and the majority of his retinue relocated to Weltevrede, for reasons which are not clear the Msiza family chose to remain at Hartbeesfontein where they continued to farm their lands. By all accounts they flourished, and by the 1950s Kgalabi's extended family settlement included the homesteads of nine sons, three of whom had two wives each. The settlement also included the home of Zondiwe Jacob Bhuda, who had married Umdundwana Amy Msiza, daughter of Kgalabi's brother, who probably joined the Hartbeesfontein community after Mfene's group had departed for Weltevrede.

The date of Kgalabi's death is not known, but can probably be assumed to have taken place during the 1930s or the early 1940s Leadership of the Hartbeesfontein community thereafter devolved upon Hlangane Speelman Msiza, his oldest son by his senior wife, Usmeshe. In time Hlangane became known to his white neighbours as Cornelius Speelman.

Msiza family make-up at Hartbeesfontein

The resettlement of the Msiza at ODI

Despite the fact that the Msiza family continued to live and farm at Hartbeesfontein, the property remained in the ownership of a family called Wolmarans. At that time it was a common arrangement for black farmers living on "white" land to exchange their labour for a small piece of ground where they could build their homesteads and plant a small crop. However, they had no title to this land, no tenure or work contracts, and could lose their homes at the whim of the white owner. By all accounts Wolmarans was considered to have been "a good man", and the Msiza remained at Hartbeesfontein for nearly sixty years. When Wolmarans died in about 1952, his son-in-law found it expedient to sell the property to the developers of the new Wonderboom airport, and the Msiza were forced to find new homes elsewhere.

By this time the Ndebele had begun to decorate the walls of their homesteads with a variety of polychromatic designs, and at an early stage the practice had come to the notice of architects, artists and anthropologists. Among them was Prof AL Meiring, Head of the School of Architecture at Pretoria University. He appears to have begun visiting the Msiza at Hartbeesfontein early in the 1950s, and at one stage he and his students drew up a detailed record of the settlement. When the family found itself in the position of being evicted from their homes, Meiring interceded on their behalf with the authorities and made it possible for them to be resettled in an area known as Klipgat, in the district of Odi, located some 50km north of Pretoria. Meiring further facilitated the move by obtaining grants of building materials for the family, most particularly timber and thatch.

By 1953 the Msiza, under the leadership of Hlangane, had rebuilt their homes at Odi and their old homestead at Hartbeesfontein had been demolished. They were joined in the move by members of the Bhuda and Skosana families, who had married Msiza women and now belonged to the extended Msiza family group. One additional family, also called Msiza but not directly related to the Kgalabi line, also made its home at Odi. Initially this move involved some 21 nuclear families, but as at least three of the men were polygamous, the number of families units was probably closer to eighteen.

In the 1960s Hlangane Msiza died, and leadership of what had by now grown into a village passed on to his brothers. Today this rests with Hlangane's last surviving brother, Maselwane Msiza who, despite his advanced age, still enjoys good health and clear thinking. His memories of events at Hartbeesfontein, and thereafter, form the basis for much of what has been related here.

Although never given an official name, the village began to appear on road signs and various large-scale maps as either KwaMapoch, Speelman's Kraal, or simply as The Ndebele Village. Its residents however, prefer the term KwaMsiza, which translates to "the place of the Msiza".

By the 1960s the village had become a popular stopping point for tourists, a factor assisted by the South African Tourist Board who placed it upon its itineraries of local attractions, and its residents had begun to supplement their income through the manufacture and sale of beaded artifacts. It did not take long for Msiza women to develop a name for themselves as excellent bead workers, and their handiwork was to inspire similar developments among other Ndebele families in the region. Articles about the Msiza and their colourful, polychromatic habitat began to be carried by numerous journals, both local and overseas, thus increasing their fame as a community of artists.

Unfortunately the agricultural lands allocated to the Msiza were neither suitable for planting, nor were they large enough to sustain the growing community. As a result many of its menfolk, as well as some of the women, were forced to enter the migrant labour market. In most cases this took them away from home for eleven months of the year, and although their income helped to sustain their families, their absence from home for such long periods had a negative effect upon the quality of life now enjoyed in the village. Most of the responsibility for the raising of children now fell upon the women, and although this was not unique to the Msiza in the context of the Apartheid society which developed in South Africa during the 1950s and 1960s, the Ndebele reaction to this oppression had some unique and interesting results. This was most marked in such areas as wall decoration and codes of ceremonial female dress.

During the 1960s and early 1970s the people of KwaMsiza were to enjoy a period of relative stability and prosperity. Assisted by grants of thatching grass and paint from the South African Tourist Board, they continued to maintain their homes to a standard which continued to attract visitors to their homes and clients for their beadwork. Work was also available, and although absent from their families as migrant workers, the men were able to earn money on a constant basis. However, by the mid-1970s the nation-wide drought had begun to have a serious effect upon the already meager crops they could grow. Their economic well-being was aggravated after June 1976 when a national student revolt made international headlines and heralded the beginning of a more intensive resistance against white Apartheid government. Although the district was not directly involved in the events of 1976, many whites were deterred from entering black residential areas by both the threat of violence as well as the ominous presence of South African security forces, and the number of visitors to the village dropped dramatically. Added to this was the fact that many men, previously employed in the migrant labour market, lost their jobs and returned home to their families, thus increasing their financial burden.