The Kingdom of Kongo was a large kingdom in the western part of central Africa. The name comes from the fact that the founders of the kingdom were KiKongo speaking people, and the spelling of Congo with a C comes from the Portuguese translation. Kingdom was founded around 1390 CE through the political marriage of Nima a Nzima, of the Mpemba Kasi, and Luqueni Luansanze, of the Mbata, which cemented the alliance between the two KiKongo speaking peoples.[i] The Kingdom would reach its peak in the mid 1600s[ii]. The Kingdom of Kongo would eventually fall to scheming nobles, feuding royal factions, and the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, initiating its eventual decline.

The Kingdom was centered around the great city of Mbanza Kongo, located in what is now northern Angola, (location: 6°16′04″S 14°14′53″E), which was later renamed to São Salvador. In 1888, what was left of the Kingdom of Kongo was made a vassal state to Portugal, and in the early 1900s it was formally integrated into the Portuguese colony in Angola[iii].

Early history and formation 1390 - 1491

Understanding the early history of the Kingdom of Kongo is complicated by the lack of written sources from the time, as well as the problematic fact that almost all of the later accounts were produced by Europeans[iv]. This means that there is a need to be critical about European accounts, as they were writing from the perspective of conquerors and outsiders. A further issue is that local chroniclers (those writing from an insider’s perspective), such as the Congolese historian Petelo Boka , made assumptions based on the organisation of clans in more recent history[v].

It is generally acknowledged, however, that the establishment of the Kingdom of Kongo came about through both the voluntary and involuntary inclusion of neighbouring states around a central core state[vi]. Much of the early territorial expansion of the Kingdom of Kongo came through various voluntary agreement with smaller neighbouring states. Some historians prefer to call state entities similar to the Kingdom of Kongo as ‘commonwealths’ rather than Kingdoms, as they were built, in part, on mutual agreement, marriage alliances and cooperation rather than conquest[vii]. Later territorial expansion in the Kingdom came to a larger degree from conquest.

The founding myth of the Kingdom of Kongo begins with the marriage of Nima a Nzima to Luqueni Luansanze, the daughter of Nsa-cu-Clau the chief of the Mbata people[viii]. Their marriage would solidify the alliance between the Mpemba Kasi and the neighbouring Mbata people, an alliance which would become the foundation of the Kingdom of Kongo. Nima a Nzima and Luqueni Luansanze had a child named Lukeni lua Nimi, who would become the first person to take the title of Mutinù (King)[ix]. Lukeni lua Nimi is presumed to have been born between 1367 and 1402 CE[x]. Historians therefore also date the founding of the Kingdom of Kongo to sometime around 1390 CE.

It is estimated that the core of the Kingdom began in the province of Mpemba Kasi in the south of Kongo, and that Lukeni lua Nimi built the capital city of Mbanza Kongo[xi]. There is speculation, however, that earlier rulers controlled a larger territory before Lukeni lua Nimi became king, and that he simply moved the capital city to that area[xii]. This was also in this period that the neighbouring province of Mbata came under the protection and voluntary subordination of the Kingdom of Kongo[xiii]. It is presumed, but not known for certain, that the Kingdom of Kongo had similar protection treaties with other smaller neighbouring states[xiv].

The early Kingdom was to some degree founded on conquest, but was largely made up of voluntary protection arrangements. With help from the Mbete and other allied provinces, the Kingdom of Kongo then conquered Mpangu and Npundi to the south[xv]. These provinces would be governed by governors who received their orders from the King.

Both Npundi and Mbata later expanded their own territories, which would in turn expand the boundaries of the Kingdom of Kongo[xvi] and Bby 1490 the Kingdom of Kongo was estimated to have around 3 million subjects in total[xvii]. The Kingdom of Kongo is believed to have had six Kings (including Nima a Nzima, despite never taking the title of King) before 1490[xviii].

The Establishment of the Catholic Church in the Kingdom of Kongo

The first meeting between Portuguese explorers and King Nzinga a Nkuwu of the Kingdom of Kongo was in 1482[xix]. Eight years later King Nzinga a Nkuwu would ask, for unknown reasons, to be baptised, and in the process would change his name to João I[xx]. The Christianisation of Kongo would cause many nobles to change their names to Portuguese variations, and it would also entail the adoption of European titles such as ‘duke,’ ‘count’ and ‘king.’

Most of the nobles converted together with the King, and all baptisms were voluntary and without incident[xxi]. It is unknown what the popular sentiment towards Catholicism was among the general population of the time. There was surely some disagreement over the King's conversion and King João I is said to have renounced Christianity in his later years[xxii]. Around 1506 João I died and was succeeded by his son, Afonso. Like his father, Afonso adopted Christianity, despite this conflicting with his brother’s desire to retain their traditional faith. There was an ensuing struggle in which Afonso and the Christians emerged victorious[xxiii].

In the centuries to follow there would be continued conflict over religion in Kongo. The Portuguese clergy would denounce several Kings of Kongo to the Pope in Rome. King Diogo I (who ruled Kongo from 1545 - 1561) was chastised by the clergy for turning away from the church and supporting an anti-Portuguese agenda, while King Álvaro III (who ruled from 1614 – 1622) was denounced for his control over local clergy[xxiv]. Many historians and social scientists argue that the Catholic Church was never as hegemonic in the Kingdom of Kongo as the Portuguese clergy was reporting[xxv]. They argue that Christianity was seen by the Kongolese as another cult which existed parallel to a multitude of other cults and religious practices[xxvi]. Some of the practices of Christianity were localised and assimilated into the already existing religious practices and beliefs within the Kingdom of Kongo.

Thus,there was no full-scale conversion to Catholicism, but rather an adoption of Christian rituals without disrupting the already existing beliefs of the area. The Portuguese missionaries and clergy were largely forced to overlook the continuation of local beliefs; as opposed to the Americas, where large scale and complete conversions were the norm, the Kingdom of Kongo was religiously and culturally strong, and the missionaries were allowed to stay only through the allowance of the King[xxvii]. This meant that the missionaries were required to tread carefully and much more diplomatically in their treatment of local beliefs.

16th century cathedral (built in 1549), which many Angolans claim is the oldest church in sub-Saharan Africa Image source

16th century cathedral (built in 1549), which many Angolans claim is the oldest church in sub-Saharan Africa Image source

Slavery in Kongo

Little is known of slavery in the Kingdom of Kongo before contact with the Portuguese in 1482[xxviii]. A number of sources state that there was an established tradition of making slaves out of people displaced by conquest in the early 1400s[xxix]. This is potentially explained by the fact that the export of slaves was central to the ability of Kongo to maintain its relationship with Portugal[xxx], which meant that Kongo needed to have a constant supply of slaves. The usage of slaves would, during this early period of slave trade, become more common within the Kingdom as well[xxxi] , although the export of slaves to Europe and the Americas would later be the cause of much instability and strife in the Kingdom.

The Portuguese began trading in Kongolese slaves very quickly after their contact with the Kingdom of Kongo. The Kongolese King would protect his own subjects, called gente or ‘freeborn’ Kongolese, from slavery[xxxii]. In the 1500s this was not a problem as the Kingdom of Kongo was experiencing a rapid population and territorial expansion through various conquests, thus providing a steady supply of foreign-born slaves[xxxiii]. Most of these slaves came from wars waged against the neighbouring Mbundu kingdom of Ndongo in around 1512[xxxiv]. While most slaves were exported to Portugal, King Afonso of Kongo retained many slaves for himself. Both King Afonso and later kings would keep slaves, particularly enslaved criminals, but these slaves were freeborn Kongolese and therefore could not be sold to other parties[xxxv].

In 1526 correspondence between the Portuguese King Joao III, and the Kongolese King Afonso, showed that the Portuguese would kidnap many freeborn Kongolese to sell into slavery (including the children of nobles)[xxxvi]. While various Kongolese nobles were sometimesimplicated in the trade of freeborn Kongolese, much of this unsanctioned slave trade is attributed to Portuguese merchants who kidnapped people off the streets and from their homes[xxxvii]. Inability to protect his subjects became an issue on the domestic front for King Afonso, as it caused him to lose legitimacy in the eyes of his people[xxxviii].

From 1568–1570, during the reign of king Álvaro I, the Kingdom of Kongo experienced a large scale conflict called the Jaga invasion[xxxix]. The source of the Jaga invasions is hotly debated by historians, but it is assumed that the Jaga were in some way related to the Yaka ethnic group. During the invasion they managed to capture the capital city of Mbaza Kogno[xl].The conflict caused an economic crisis in the Kingdom, the severity of which caused fathers would sell their sons, and brothers to sell their brothers into slavery as a means of survival[xli]. An unprecedented amount of freeborn Kongolese were sold to the Portuguese during this time, including princes and nobles.

The Kings of Kongo proclaimed upon their coronation their duty to protect all of their subjects, rich and poor. As such, they swore to protect even their enslaved subjects, and the Kings who reigned during the 1500s were mostly successful in preventing their subjects from being transported across the Atlantic as slaves[xlii]. Following the widespread selling of slaves during the Jaga invasion, for example, King Álvaro became incensed by the sale of his subjects. He thus sent an emissary to São Tomé, where the slaves where held prior to transportation across the Atlantic, to ransom them[xliii]. Most of the people enslaved during in the aftermath of the Jaga invasion were allowed to return home and the nobles were integrated into the administration of the King. This indicates that when the central authority of the King was strong, he was in fact able to protect his subjects.

However, after 1590 several civil wars and rebellions weakened the King’s authority and caused an increasing amount of Kongolese subjects to be enslaved[xliv]. A major obstacle for the Kingdom of Kongo was that slaves were the only commodity which foreign powers were willing to trade for, and this meant that Kongolese kings had no international currency other than people[xlv]. Slaves became the tool through which Kongo developed and sustained their material, cultural and diplomatic ties with the European powers[xlvi]. Kongolese nobles could buy slaves with the local currency, nzimbu shells, and the slaves could in turn be traded for international currency. As an example of how slaves were used as an international currency we can see how the Kongolese authorities paid the Catholic church in slaves for bishops to preform various religious duties in the Kingdom[xlvii].

There needed to be a constant source of slaves for Kings to sell in exchange foreign commodities, the absence of which would prevent them from buying influence with foreign powers such as Portugal and the Dutch. Kongolese kings would desperately need this influence to garner support from European powers for quelling internal rebellions in the Kingdom and to aid them against other colonial empires[xlviii]. To illustrate, in 1641 King Garcia of Kongo required the help of the Dutch military, and paid them in slaves for their assistance in defeating the counts of Soyo (a growing city in the northern part of the Kingdom) after they declared independence.

Since the Kingdom of Kongo had stopped their conquests of expansion in the early 1600s, the supply of foreign slaves were drying up. Rebellions like the Soyo rebellion became the Kingdom’s new way of supplying slaves[xlix]. During the mid-1600s it became common practice for freeborn Kongos to become slaves through a variety of infractions, such as disrespecting nobles, stealing from gardens, rebelling against the central authorities, and disciplining seditious nobles[l]. In fact, if several villagers were deemed guilty of a crime, the whole village was sometimes enslaved[li].

The chaos and internal conflict of the late 1600s and 1700s would mean the end of the King's protection of his subjects from slavery; in this period every Kongolese person was in danger of being enslaved, and this caused further instability within the Kingdom[lii]. During this period of internal conflict a large amount of captives of war, refugees, and conquered peoples were captured by British, Portuguese and Dutch slave traders and shipped across the Atlantic.

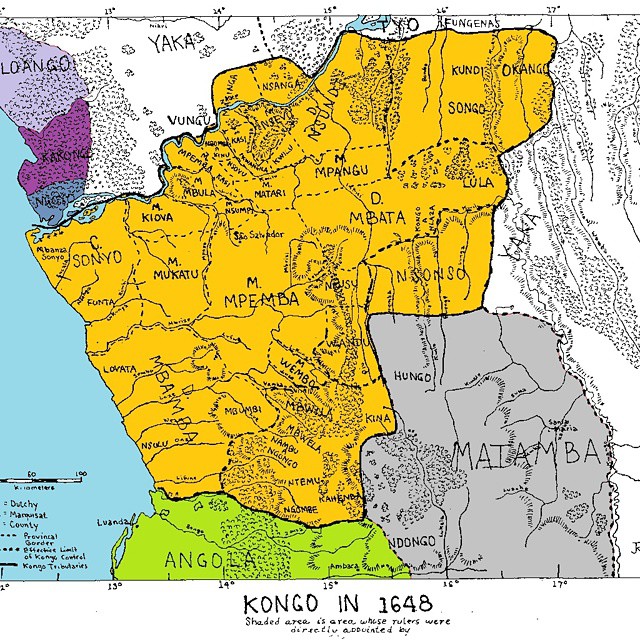

Kongo in 1648 Image source

Kongo in 1648 Image source

Internal Conflict, Factionalism and Civil War in the Kingdom of Kongo (1641-1718)

Before 1641 the Kingdom of Kongo had managed to fight off several Portuguese incursions and had remained a strong and centralised state. In the years following 1641 this would change drastically.

Aside from the divisive issue of slavery, the split within Kongo had already begun in 1593 with the internal conflict between Sonyo, one of the richest provinces in the Kingdom of Kongo[liii] and home to the Counts of Soyo, and the Kongolese state[liv]. In 1641 the Soyo declared independence under Count Daniel da Silva, and King Garcia II of Kongo declared war against the rebels[lv]. The same year also saw a rift in the relationship between Portugal and Kongo, when a joint Kongo-Dutch force worked together to expel the Portuguese from Luanda.

More than two decades later, in 1665, the oppurtunistic Portuguese colonisers invaded the Kingdom of Kongo and battled the Kongolese forces in the Battle of Mbwila[lvi]. The Kongolese forces lost and King António I of Kongo was killed by Portuguese soldiers[lvii]. The Portuguese also seized the island of Luanda, an important source of the local currency; Nzimbu shells[lviii]. The defeat of Kongolese forces and the death of King António I was to cause further internal strife in the Kingdom.

After the death of King António I, two royal factions - the Kimpanzu and the Kinlaza - competed for power and divided much of the country between them[lix].Meanwhile, the civil war between Soyo separatists and the Kingdom of Kongo raged on, while both sides attempted to garner the support of European powers of Holland, Brazil and Portugal to aid them. In 1670, despite having fought each other five years earlier, a joint Portuguese and Kongolese force invaded Soyo and were in turn soundly defeated by Soyo forces[lx].

The Soyo manipulated and exacerbated the post-António I conflict between the Kimpanzu and the Kinlaza with the intention of creating further instability in the Kingdom of kongo[lxi]. During the skirmishes between the Kimpanzu and the Kinlaza, the capital city of Kongo (now called, São Salvador) was sacked in 1669 by the Soyo and then completely destroyed during an attack by Pedro III of the Kinlaza faction in 1678[lxii]. The capital was later rebuilt and some former residents returned, but it would never reach its previous size.

The two factions established separate capitals; the Kinlaza faction in the mountain fortress of Kimbangu, and the Kimpanzu faction in the northern town of Mbula[lxiii]. The Kingdom of Kongo experienced a great degree of decentralisation during this period of intrastate war. People and bands of warriors moved vast distances and resettled in new provinces. One general, General Pedro Constantinho da Silva, moved his army across the country and in1705 resettled his whole army in the rebuilt São Salvador[lxiv]. Pedro Constantinho da Silva was defeated by King Pedro IV of the Kinlaza faction in 1709 when he attacked the army outside of the former capital[lxv].

The the period between 1641 and 1718 was marked by several ongoing conflicts between a variety of different factions. There were independence movements such as the Soyo, and there were competing royal dynasties such as the Kimpanzu and the Kinlaza. There were also conflicts between foreign powers such as the Portuguese. In the beginning of the 1700s King Pedro IV had, however, managed to subdue the rival Kimpanzu faction led by King João II[lxvi]. In 1715 João II recognised Pedro IV as the rightful king of Kongo and in the same year, several other internal conflicts came to an end[lxvii].

There is much debate between academics and historians as to why the Kingdom of Kongo fell apart so rapidly in the mid 1600s. Certainly, the pressures of the slave trade and its constant demand for more slaves de-legitimised the power of the king[lxviii]. This weakened the monarchy, as did Portuguese military expeditions against the Kingdom. Further instability stemmed the death of King António I which directly triggered the civil war[lxix]. The third, and some argue, the most plausible reason for the decline of the Kingdom of Kongo was the conflict between the Counts of Soyo and the Kings of Kongo[lxx].

In the 1500s the city of Mbaze Soyo grew very wealthy on the slave trade[lxxi]. The city would at its height have a large population, and was located in the already wealthy province of Sonyo. This created two centres of power; one in Soyo, and one in São Salvador[lxxii]. The Counts of Soyo were, for a while, loyal towards the Kings of Kongo (King Pedro II was related to the then count of Soyo). Later counts such as Daniel da Silva, however, became extremely hostile towards the Kingdom of Kongo. By 1680 Soyo had grown so strong and independent they could muster between 20 000 and 25 000 soldiers, and styled themselves the Princes of Soyo[lxxiii].

The rise of a new centre of power together with the external pressures of colonialism and slavery and increasing in the Kingdom all contributed to the cause of the civil war. The Kingdom of Kongo survived after King Pedro IV emerged victorious, but his descendants would only rule directly over a fraction of the previous Kingdom[lxxiv]. The structures of power and prestige established around the city of São Salvador was an important part of what kept the Kingdom together, and by 1718 these structures had been completely destroyed by the civil war.

List of kings and their affiliated faction during the period of internal conflict:

Antonio I (who's death in battle against Portugal sparked the internal conflict)

Alfonso II of the House of Kimpanzu

Alvaro VII of the House of Kinlaza

Alvaro VIII of the House of Kimpanzu

Pedro III of the House of Kinlaza

Alvaro IX of the House of Kimpanzu

Rafael I of the House of Kinlaza

Afonso III of the House of Kimpanzu

Daniel I of the House of Kimpanzu

Garcia II of Kibangu (Ruled around the Kibangu area only)

André I of Kibangu (Ruled around the Kibangu area only)

Manuel Afonso of the House of Kimpanzu (Ruled around the Kibangu area only)

Alvaro X of the House of the Agua Rosada (Ruled around the Kibangu area only)

Pedro III of the House of Kinlaza (Ruled around the Mbula area only)

João Manuel II of the House of Kinlaza (Ruled around the Mbula area only)

Pedro IV of the House of the Agua Rosada (Reunited the Kingdom under one ruler again in 1709)

Flag of Kingdom of Kongo Image source

Flag of Kingdom of Kongo Image source

A Century of Decentralisation and the Decline of the Kingdom (1718 - 1914)

The Kingdom of Kongo was, from the 1700s, a decentralised Kingdom largely dependant on slave labour and armies[lxxv] to maintain control. This century saw the emergence of clans as important political actors, especially because the clans would join together to elect the Kings. As part of a peace agreement between the two warring factions, King Manuel II of the Kimpanzu faction was crowned king in 1718[lxxvi]. The area he would rule over only included São Salvador and Kimbangu. After his death in 1743 King Garcia IV, a member of the Kinlaza faction, assumed power[lxxvii]. During Garcia IV's reign, São Salvador was again recognised as the capital of the entire Kingdom, thus ending the final rivalries of the civil war[lxxviii].

This was not to last, and in 1763 the Kingdom saw renewed internal strife as Alvaro IX and Pedro V both claimed the throne. This contestation led to renewed hostilities between the Kimpanzu and Kinlaza factions, and in 1781 a battle compromising of about 30 000 soldiers was fought outside of São Salvador[lxxix]. The Kinlaza faction emerged victorious and Jose I became King, later passing the crown on to his brother Afonso V in 1785[lxxx]. Afonso V is thought to have been poisoned in 1794 and Henrique I was crowned the King of Kongo[lxxxi].

Henrique I again attempted to centralise power within the monarchy, and as a result he was driven from court at São Salvador[lxxxii]. He returned with an army in 1802 or 1803 only to be defeated and deposed as King[lxxxiii]. In this period of back-and-forth struggle between several factions, who had by now splintered off from the Kimpanzu and Kinlaza factions, São Salvador became an important symbolic centre of power. While it was the capital of the country, it had a mostly token population and kings like Henrique I drew theire power and military forces from outside the city[lxxxiv]. Henrique I was even crowned on the outskirts the city[lxxxv]. This stands in contrast with previous centuries where the majority of power of the Kings and nobles aome from São Salvador itself.

The power struggle between various factions over who was going to rule continued into the 1800s, further eroding the legitimacy and power of the kings[lxxxvi]. In 1842 Henrique II, representing a new faction called the Kivuzi, was crowned King[lxxxvii]. The new faction would be short lived, and disputes about succession continued.

One of the largest changes to happen in the Kingdom of Kongo during the mid 1800s was not political, but economic; by 1839 the British had abolished the slave trade, and were patrolling the shores of Kongo to ensure that no ships would transport slaves across the Atlantic[lxxxviii]. This meant that the main source of foreign revenue in the Kingdom was drying up, causing the Kingdom to shift its economic emphasis to trade in ivory and rubber which were becoming dominant parts of the Kingdom’s economic makeup[lxxxix].

The rubber trade in particular was not dependant on large armies and centralised power as the slave trade had been. What was essential for the rubber trade was a small and mobile workforce[xc]. Since the rubber grew inland, large parts of the population moved inland to harvest and sell it to European traders. The larger population-dense villages and cities which had been the main source of power for the Kongo nobility and royalty disappeared[xci]. Mobility had always been an essential part of Kongolese society, and people could break down entire houses and move them at short notice[xcii]. By 1880 most of the Kingdom of Kongo was now made up of small, decentralised trading villages[xciii].

During the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885 European powers decided that Portugal would take most of what remained of the Kingdom of Kongo, and Belgium would take the rest. For Portugal to claim their part they were also required to occupy the territory[xciv]. Portugal, however, had limited military success against the Kingdom of Kongo in the past, and they needed an alternative route to conquest. An opportunity for occupation arose in 1883 when King Pedro V was embroiled in fighting a rival faction lead by Alvaro XIII[xcv]; Pedro V invited the Portuguese into an alliance to aid him in efforts to supress his rival, and in return Portugal would station soldiers in São Salvador[xcvi]. In 1888 the Portuguese forces defeated Alvaro XIII and occupied São Salvador, making King Pedro V a vassal. The Portuguese demanded rights to collect taxes and trade revenues[xcvii] , which effectively ended the independence of the Kingdom of Kongo. By the early 1900s the Kingdom was integrated into the Portuguese colony of Angola[xcviii].

Endnotes

[i] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 105. ↵

[ii] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 13. ↵

[iii] Thronton, John. 2000. “Mbanza Kongo/Sao Salvador: Kongo's Holy City” in Africa's Urban Past (eds.) David Anderson and Richard Rathbone. Oxford: James Currey Ltd. Page 73. ↵

[iv] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 91. ↵

[v] MacGaffey, Wyatt. 2003. “Crossing the River: Myth and Movement in Central Africa” From International symposium Angola on the Move: Transport Routes, Communication, and History,Berlin, 24-26 September 2003. Page 2. ↵

[vi] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 104. ↵

[vii] MacGaffey, Wyatt. 2003. “Crossing the River: Myth and Movement in Central Africa” From International symposium Angola on the Move: Transport Routes, Communication, and History,Berlin, 24-26 September 2003. Page 3. ↵

[viii] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 105. ↵

[ix] Ibid. ↵

[x] Ibid. Page 106. ↵

[xi] Ibid. Page 107 – 110. ↵

[xii] Ibid. Page 110. ↵

[xiii] Ibid. Page 111. ↵

[xiv] Ibid. ↵

[xv] Ibid. Page 114. ↵

[xvi] Ibid. Page 115. ↵

[xvii] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 28. ↵

[xviii] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 105. ↵

[xix] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 30. ↵

[xx] Thornton, John. 1984. “The Development of an African Catholic Church in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1491-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 25, No. 2 (1984), pp. 147-167. Page 148. ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. Page 149. ↵

[xxiv] Ibid. Page 151. ↵

[xxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxviii] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 2. ↵

[xxix] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[xxx] Ibid. Page 3. ↵

[xxxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[xxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxv] Ibid. Page 5. ↵

[xxxvi] Ibid. Page 6. ↵

[xxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxix] Ibid. Page 7. ↵

[xl] Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 18, No. 4 (1977), pp. 507-530. Page 519. ↵

[xli] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 7. ↵

[xlii] Ibid. Page 8 ↵

[xliii] Ibid. ↵

[xliv] Ibid. Page 6. ↵

[xlv] Ibid . Page 8. ↵

[xlvi] Ibid. Page 3. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid. Page 10. ↵

[xlviii] Ibid. Page 9 ↵

[xlix] Ibid. Page 12. ↵

[l] Ibid. Page 13. ↵

[li] Ibid. ↵

[lii] Ibid. Page 22. ↵

[liii] Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 18, No. 4 (1977), pp. 507-530. Page 519. ↵

[liv] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 8. ↵

[lv] Ibid. Page 11. ↵

[lvi] Thornton, John. 1998. Warfare in Atlantic Africa. London: University College of London Press. Page 117. ↵

[lvii] Ibid. Page 122. ↵

[lviii] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 34. ↵

[lix] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[lx] Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 18, No. 4 (1977), pp. 507-530. Page 520. ↵

[lxi] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[lxii] Ibid. Page 85. ↵

[lxiii] Ibid. Page 82. ↵

[lxiv] Thornton, John. 1998. Warfare in Atlantic Africa. London: University College of London Press. Page 118. ↵

[lxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxvi] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 113. ↵

[lxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxviii] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 22 . ↵

[lxix] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[lxx] Ibid. Page 54. ↵

[lxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxiii] Thornton, John. 1998. Warfare in Atlantic Africa. London: University College of London Press. Page 117 and 118. ↵

[lxxiv] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 115. ↵

[lxxv] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 19. ↵

[lxxvi] The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 115. ↵

[lxxvii] Thronton, John. 2000. “Mbanza Kongo/Sao Salvador: Kongo's Holy City” in Africa's Urban Past (eds.) David Anderson and Richard Rathbone. Oxford: James Currey Ltd. Page 73. ↵

[lxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxix] Ibid. ↵

[lxxx] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxi] Ibid. Page 74. ↵

[lxxxii] Ibid. Page 75. ↵

[lxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxvii] Ibid. Page 76. ↵

[lxxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxix] Ibid. ↵

[xc] Ibid. ↵

[xci] Ibid. ↵

[xcii] Ibid. ↵

[xciii] Ibid. ↵

[xciv] Ibid. Page 78. ↵

[xcv] Ibid. ↵

[xcvi] Ibid. ↵

[xcvii] Ibid. ↵

[xcviii] Ibid. ↵