King Kong: An African Jazz, was the first all-Black South African musical which opened in 2 February 1959. The musical chronicles the rise and fall of champion boxer Ezekiel ‘King Kong’ Dhlamini. It helped create a new set of opportunities for Black South Africans in the arts and has taken South African theatre to new dimensions.

Made possible through the Union of South African Artists and Ian Bernhardt, the musical’s creative team was led by Harry Bloom, best known for his book Episodes, Todd Matshikiza - a well known composer, and Clive Menell, an imaginative business executive with an keen interest in the arts. He made his studio available for the creation of the work and which would become an international masterpiece. They would be joined by architect and painter Arthur Goldriech, which led to the flow of many creative ideas. Later the creative team was joined by journalist Pat Williams who took over the scriptwriting after Bloom’s departure. Leon Gluckman joined the team as the producer and he later assembled a production team of people he had previously worked with.

King Kong is based on the life of Ezekiel Dhlamini, a young man who was born in 1925 in the Vryheid District of Natal. The first of six children, he left home at the age of 14 to find work as a garden boy. Shortly after this employment, he found his way to the south of Natal, landing in Durban, but would soon find himself lured by the stories of streets paved in gold, as he made his way to Johannesburg.

His survival on the streets of Johannesburg was based primarily on playing cards and dice and he would occasionally hang out at clubs and dance halls. He moved around a lot until he found himself in the sparring rooms of the Bantu Men’s Social Center. A confrontational man, he would often taunt and challenge the fighters as they practiced, and he would laugh at them for using boxing gloves.

A troubled and aggressive man, he trained to become a boxer professionally and would go ahead to win many championships. He lived his life instilling fear in people and dared people to challenge him, and when no one would respond, he began to fall from grace. He eventually found himself serving a jail sentence for killing his long-time girlfriend. He committed suicide at the age of 32, only two weeks after he began serving his sentence.

King Kong came alive again in the new theatre musical based on his life. After months of preparation and auditioning of cast members, King Kong was ready to be shown on the stage. Many of the cast members were budding musicians and artists but very few had any theatrical experience with only three of them having had experience in Athol Fugard’s No Good Friday.

With a cast of 70 there was Gwigwi Mrwebi, Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Phyllis Mqoma and many others who would go on to have great careers in the arts.

The production was not without its challenges, with the pass laws rife and full in force in apartheid South Africa. There was always an actor who would get arrested for pass law violation and would have to be bailed out the next morning. There were tensions felt from some of the Black community as well, as some gangsters who had been said to have tangles with the real King Kong were worried about how much the play would reveal and made threats to some cast members, including Todd Matshikiza, who was told that his house and car would be burnt down. These threats subsided when they realised that the play did not reveal any criminal secrets.

The reception of the show

Opening night was set for the Wits Great Hall on the 2February 1959. Doors were opened from 7:30pm and people began to show up in numbers. In the crowds were the influential people of Johannesburg, the mayor, mining and business moguls, politicians and people that frequented opening nights. Nelson Mandela was also in attendance. The rest, including many musicians, had come out to see what the hype was about, as the event had been highly publicised.

The show was a hit. Bookings were coming in the thousands, to such an extent that the Johannesburg Cinema managers were curious about the duration of the show as it was beginning to affect their show attendances. Eventually people had to be turned away as the show was sold out by 10 February.

By early April, 37 performances had been made to a total of 40 000 audience members. Performing for White and for Black audiences did have its challenges as the cast would often find a strange contrast in the reception and reaction to the show, as it highlighted the cultural differences; the White crowd having been accustomed to theatre and the structure of the plays while the Black audience being new to this kind of scene would often miss some theatrical cues and often had questions about the theatre structure.

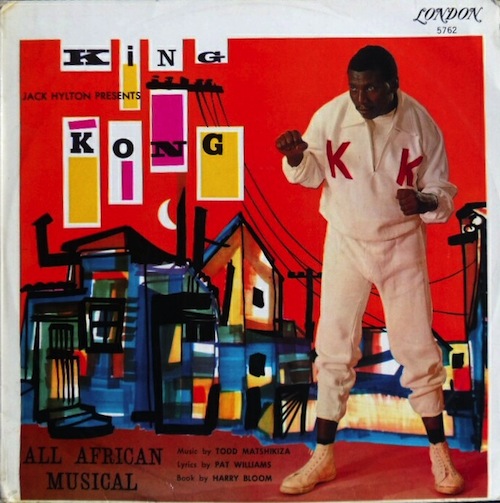

Todd Matshikiza & Pat Willams King Kong (Gallo, 1959) Image source

Todd Matshikiza & Pat Willams King Kong (Gallo, 1959) Image source

In mid-April the King Kong cast arrived at the Cape Town station where they were greeted by the press, fans and penny-whistlers who would whistle the tune to “Little Kong Kwela”. From there the show moved to Durban where once again the press and public response to the show was outstanding. The show was next scheduled to show at The Feather Market Hall in Port Elizabeth, which became quite a bit of work as the hall was not designed to accommodate a big theatre production.

Approval was eventually granted by the City Council for alterations to be made to the hall and the show was scheduled to open and once again public response was outstanding. From there the show went back to Johannesburg for another run from the 1 to the 11 July.

The King Kong record helped catapult the careers of many involved in the show including Miriam Makeba, whose voice was heard by an English record company and as a result, she was offered a contract to sign with them which lead to her finding international fame.

Lord Derby, a partner of London theatre promoter Jack Hylton had seen the first show of the production and shown an interest in taking it abroad. The negotiations were made and approved and plans were set in motion for the cast to head to London.

The show was set to open on the 20 February at the Prince Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue. In preparation for opening night, Nathan Mdledle, who played the role of Ezekiel Dhlamini said “if the London cats like it, we’re in”, and as the London audience cheered through fifteen curtain calls, they certainly were in.

The success of King Kong did wonders to bridge the artistic gap between the Black and White community as it helped many to put aside many apartheid beliefs, even if for a night, and for many of the artists it was a step in the right direction for South African artists. It opened many doors for local theatre and South African storytelling.