Contents

Discriminatory legislation up to 1924

Introduction ↵

The 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging between the British and the Boer republics ended the Second Anglo Boer War. This period saw a cordial relationship being forged between the British and the Afrikaners, to the exclusion of black people. As one author put it, “ While the Boers and the Britons half heartedly shook hands both joined in declaring a political war on the black people by blocking their political expectations “ (Brits and Grundlingh, 1998: 36). Article 8 of the Treaty made voting rights by black people conditional on the consent of the white majority. This effectively blocked black access to political power. The British High Commissioner at the time, Lord Alfred Milner, appointed the South African Native Affairs Commission in 1903, headed by the Commissioner for Native Affairs, Sir Godfrey Lagden. Its work was to devise a common policy for black people.

Picture A: Sir Godfrey Lagden. Image source

Picture A: Sir Godfrey Lagden. Image source

The recommendations of the Lagden Commission were far reaching and supported future segregatory legislation. The Commission’s report issued in 1905 supported and recommended a political system based on racial separation including the principle of legislated racial segregation and territorial separation of black and white people, and urban segregation in the form of locations. The recommendations aimed to address the main issues raised in the ‘Native Question’ around tenure and the position of rural dwellers, the problems presented by the urban groups as well as the question of political role and voting rights of black people.

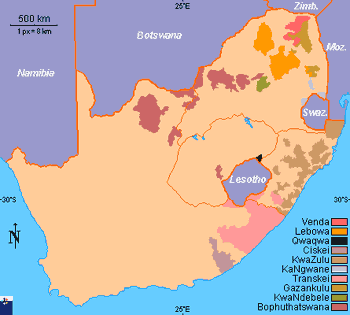

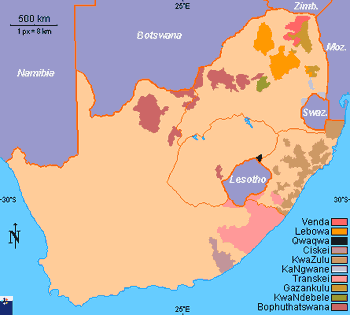

Following these recommendations on 19 June 1913 the Union government passed the Natives’ Land Act that prohibited black people from owning or renting land outside special areas called reserves (later called bantustans or homelands). These reserves made up only 7% of the land in South Africa and were converted from existing “tribal” areas, mainly in Zululand, the Ciskei and Transkei. It effectively divided the land between black and white people and segregated the two groups. It also restricted the size of the property that people could own inside the reserves and prevented the majority of black people from surviving off subsistence farming as there wasn’t enough land for everyone to grow sufficient food for the household. Many people were forced to leave their homes and migrate to urban areas in order to earn wages to pay compulsory taxes and support their families. The Act also undermined the rights of black sharecroppers on white farms. In 1936 further legislation completed the distribution of land from the 1913 Act and increased the amount to 13%.

Map A: The reservations, Bantustans or homelands. Image source

Map A: The reservations, Bantustans or homelands. Image source

Learning Outcomes: Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Ability to work independently, formulating questions and gathering, analysing and interpreting relevant evidence to answer questions. Understanding of public representations and exploration of ways the past is memorialised in different knowledge systems.

The concept of segregation ↵

The idea of segregation

“ A political equality of white and black is impossible. The white man must rule, because he is elevated by many, many steps above the black man; steps which it will take the latter centuries to climb, and which it is quite possible that the vast bulk of the black population may never be able to climb at all “ Lord Alfred Milner, 1903.

Picture A: Lord Alfred Milner. Image source

Picture A: Lord Alfred Milner. Image source

The concept of formal racial segregation is unique to South Africa and at its most basic the term is taken to mean, “ enforced separation of racial groups in a community … the state of being segregated “. On another level, segregation should be seen as a process that separated people along racial lines. In order to legalise, implement and maintain this separation, laws had to be enacted. These laws shaped the political, economic and social fabric and experience of black, Coloured, Indian and white people in South Africa.

The South African government entrenched segregation within the political shape of the country by passing a range of laws that separated white from other South African races.

The following section looks at how the state’s policy of segregation developed and how various pieces of legislation built this policy into the foundation for Apartheid.

Learning Outcomes: Synthesise information about the past and develop, sustain and defend an independent line of historical argument. Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Discriminatory legislation up to 1924 ↵

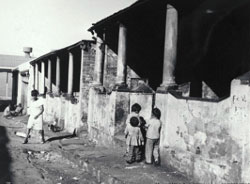

The starkest piece of discriminatory legislation prior to 1924 was the Natives Land Act of 1913. This act was responsible for the forced removal of black people in South Africa. The movement of black people was severely restricted as their movements outside the reserves were directed by their relations with white industry and farms.

Picture A: Many people in the reservations followed traditional lifestyles, but lived in poverty as the reserves barely supported their survival. This led to migration of people to the cities in search of jobs and survival. Image source

Picture A: Many people in the reservations followed traditional lifestyles, but lived in poverty as the reserves barely supported their survival. This led to migration of people to the cities in search of jobs and survival. Image source

Picture B: Many people in the reservations followed traditional lifestyles, but lived in poverty as the reserves barely supported their survival. This led to migration of people to the cities in search of jobs and survival. Image source

Picture B: Many people in the reservations followed traditional lifestyles, but lived in poverty as the reserves barely supported their survival. This led to migration of people to the cities in search of jobs and survival. Image source

The Native Land Act affected both the farming and mining sectors. Much of the land set aside for black people was small or unsuitable for agricultural activities. Large numbers of black men had to work for white farmers in order to survive. The emergence of a migrant workforce is regarded as a direct result of the Land Act. The reserves barely provided subsistence and permanent ‘homes’, and most black people could not make a decent living. As a result of this, the mining boom and the need for cheap labour in urban areas, black men were attracted to the mining industry. By linking the supply and distribution of labour to territorial segregation, the 1913 Land Act laid the foundations for Apartheid’s Bantustan policy in later years.

Picture C: Many young black men were recruited, or forced by circumstances, to work on gold mines on the Witwatersrand. Image source

Picture C: Many young black men were recruited, or forced by circumstances, to work on gold mines on the Witwatersrand. Image source

On the labour front the Mines and Works Act, or Colour Bar Act, of 1911 was introduced. This legislation is seen as the cornerstone of job reservation, or the allocation of jobs on the basis of race. It prevented black workers from getting skilled employment on the mines. The Native Labour Regulation Act of 1911 reinforced the pass law system, which severely restricted the movement of black workers from one area to another. Under this Act the lack of possession of the correct pass documentation was a criminal offence. Unlike today, black workers had no access to or form of dispute resolution, because they were denied recognition as workers and did not have the right to strike. This was laid out in the Industrial Conciliation Act of 1924.

Picture D: Locations sprung up outside white urban areas. Image source

Picture D: Locations sprung up outside white urban areas. Image source

As seen from the recommendations of the Lagden, or South African Native Affairs, Commission in 1905 the state had been increasingly concerned with setting up political structures that would control South Africa’s black population. In 1920 the Native Affairs Act came into being and paved the way for the establishment of a Native Affairs Commission, headed by the Minister of Native Affairs. This organisation worked towards the creation of a countrywide system of tribally based district councils that were to consider and make recommendations on any matter relating to the general conduct of the administration of black people.

Three years later, in 1923, the Native (Urban Areas) Act came into force and cemented the state’s segregationist policy. This Act gave local authorities the power to identify and establish black locations on the outskirts of white urban and industrial areas. Measures were introduced to control by local authorities of trading, brewing of beer, fines and rents to be levied. More importantly it empowered local authorities to declare black workers “idle, dissolute or disorderly” and have them deported to the reserves. As a result those people who could not longer be of benefit to industry were deported, whilst ensuring that there was a permanent supply of healthy labour for white-owned industries.

Learning Outcomes: Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Synthesise information about the past and develop, sustain and defend an independent line of historical argument.

Political Legislation ↵

When the Pact Government under J. B. M. Hertzog came to power in 1924 it set about dealing with the ‘native problem’. The solution for this ‘problem’ was seen as segregation. Herzog introduced Bills that sought to remove the Cape and Natal black population from the common voters’ roll and established a national system of political representation for black people, entailing a separate form of parliamentary franchise. He also launched Bills to release more land for black people and to gradually extend voting rights to the Coloured people in the Transvaal, Natal and the Orange Free Sate.

Herzog was unable to get a sufficient parliamentary majority to turn these ambitions into laws, but he did manage to realise a far-reaching political and administrative system of segregation. The Natives Administration Act of 1927 was key to achieving Herzog’s goal of a “difference in treatment of Natives and Europeans”. This Act empowered the state to rule by proclamation in all black areas and limited the ordinary courts’ powers to intervene in ‘black affairs’. It also gave more authority to traditional Chiefs and Headmen, who were salaried officials of the state. The authority to rule by proclamation meant that lengthy legal processes would not have to be followed in relation to ‘black issues’ as this law allowed the state flexibility, or a free hand, when it came to these matters.

Picture A: J. B. M. Hertzog. Image source

Picture A: J. B. M. Hertzog. Image source

The Bills proposed by Hertzog in the 1920s finally got the two-thirds majority vote required to be passed into laws in 1936. The Development Trust and Land Act, or Native Trust and Land Act, the Bantu Trust and Land Act and the Representation of Natives Act were passed. The Representation of Natives Act stripped black people in the Cape of their voting rights replacing these with a limited form of parliamentary representation through special white representatives. A Natives Representative Council (NRC), which was an advisory body, was also created under this Act. The NRC could make recommendations to Parliament or Provincial Councils “on any legislation regarded as being in the interest of Natives”.

The Development Trust and Land Act of 1936 complimented the Representation of Natives Act and allowed for a further 6.2 million hectares of land to be added to the black reserves of the 1913 Land Act. It also established the South African Native Trust, which became the Bantu Trust and later the Development Trust. The function of the Trust was to acquire and administer all released land. This meant that black people were not permitted to own land in their own right. Many black people found themselves owning their land but with this ownership illegal as their land was in a white area, now prohibited by law. These locations became known as a “black spots”, and were later the target of forced removals.

The Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 brought the total amount of land reserved for Africans to approximately 13 % of the total land in South Africa. 87% of South Africa’s population were black people, but they only had access to 13 % of the land.

Map A: On this map you can see the old provinces of South Africa with the reservations clearly marked. Black people may have made up the majority of the population, but they were assigned the smallest amount of land. Image source

Map A: On this map you can see the old provinces of South Africa with the reservations clearly marked. Black people may have made up the majority of the population, but they were assigned the smallest amount of land. Image source

Around this time the government was paying special attention to the question of influx control and in 1932 the Holloway Commission was tasked with investigating the general economic circumstances of black people. The Commission recommended that the pass system be abolished and that black workers living in the cities be considered permanent residents. Nothing came of the recommendations, and instead influx control was intensified with various amendments to the Native Urban Areas Act. In 1937 this Act gave powers to municipalities allowed them to remove unemployed black people from within their jurisdiction. At this time the burgeoning black urban population was observed with growing nervousness and fear.

The Young Committee in 1939 and the Fagan Commission in 1948, like the Holloway Commission, were critical of migrant labour system and pass laws. Government ignored these views and became more proactive and vicious in its policies toward black people.

Learning Outcomes: Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Ability to work independently, formulating enquiry questions and gathering, analysing and interpreting relevant evidence to answer questions.

Synthesise information about the past and develop, sustain and defend an independent line of historical argument.

Economic Legislation ↵

The Pact Government under Hertzog passed a great deal of legislation that was interactive, or linked. Economic and political laws passed in this period had the objective of white supremacy and control of black people. The Industrial Conciliation Act of 1924 paved the way for Industrial Councils, made up of representatives from employers’ associations and labour unions. This Act allowed Coloured, Indian and white workers to form registered trade unions and gave them access to industrial relations facilities. The Act excluded black workers by its very definition of employee. Representation for black workers was limited to a system of factory-based legislative work committees.

Boer family. Image source

Boer family. Image source

The Wage Act of 1925 was designed to help unskilled white workers, in particular "Poor Whites". The Act sought to keep black workers at the bottom of the heap as far as jobs were concerned by limiting their participation to unskilled work. The second Colour Bar Act, or Mines and Works Act of 1926 created a Wage Board for industries where labour was not unionised or was unskilled. The Mines and Works Act protected white workers from the skilled trades so they did not get competition from black and Indian workers. Coloured workers seemed to be favoured by the law but were in reality in the same position as black and Indian workers.

The Colour Bar policy was part of Hertzog’s ‘Civilised Labour' policy strategy. Increased revenue pointed to better wages and improved living standards of black skilled labourers. Economic advancement by black workers posed a threat to white labour and political power as economic strength could spread to the political sphere. The civilised labour policy was developed to ensure continued political and economic supremacy by the government in the face of rapid changes in the industrial sector. This policy was about maintaining white standards of living and privilege, because job reservation for white workers denied economic opportunities for black workers.

Learning Outcomes: Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Ability to work independently, formulating questions and gathering, analysing and interpreting relevant evidence to answer questions.

Legislation regarding Indians ↵

Before the turn of the century legislation had been passed concerning the rights of ownership and residence of Indians in South Africa. In terms of the Transvaal Law No 3 of 1885, Indian people could own properties in special streets, wards or locations. The result is what is commonly found in most cities in South Africa, the Indian Bazaars, or markets.

Picture A: Indian bazaars or markets selling goods for an Indian customer base was partly the result of legislation that permitted Indian entrepreneurs to conduct business in certain areas. Here are Indian hawkers in Johannesburg’s first market. Image source

Picture A: Indian bazaars or markets selling goods for an Indian customer base was partly the result of legislation that permitted Indian entrepreneurs to conduct business in certain areas. Here are Indian hawkers in Johannesburg’s first market. Image source

From 1924 to 1948 an enormous amount of anti-Indian legislation was passed in South Africa focused on limiting Indian trade and business. In 1924 the Township Franchise Ordinance was passed in Natal. This deprived Indians of municipal franchise, or voting rights. Along with the Rural Dealers Ordinance the laws aimed to cripple Indian trade. The Durban Land Alienation Ordinance was also passed in 1924 to prevent Indian ownership of land in white areas.

The Transvaal Dealers (Control) Ordinance of 1925 made it difficult to get business licences and the Minimum wages Act led to a form of job reservation in favour of white job seekers. The Class Areas Bill was passed in 1925 was designed to segregate white and Indian people. On 23 July 1925 the Areas Reservation and Immigration and Registration (Further Provision) Bills were passed, defining Indians as aliens and recommending limiting the population by sending them back to India.

In 1926 the Mines and Works Amendments Act, or Colour Bar Act required certificates of competency for skilled work from which Indian workers were excluded. The Liquor Bill of the same year stipulated that Indians and black people could not be employed by liquor licence holders and were forbidden on licensed premises and liquor supply vehicles. The Bill became an Act on 23 June 1927 and 3000 Indians employed in the brewery trade were affected. On 2 January 1928 Section 104 of the Liquor Bill was withdrawn and Indians were again allowed to enter licensed premises. The Local Government (Provincial Powers) Act of 1926 denied Indians citizenship rights.

Picture B: Many Indian people in South Africa lived in poverty as a result of the anti-Indian legislation passed by the government of the time. Indians could only live and trade in certain areas.

Picture B: Many Indian people in South Africa lived in poverty as a result of the anti-Indian legislation passed by the government of the time. Indians could only live and trade in certain areas.

On 27 April 1927 the Immigration and Indian Relief (Further Provision) Bill was introduced by Minister of the Interior, Dr D. F. Malan. It required children of South African Indian parents, born outside the Union, to enter the country within three months of birth. Indian South Africans who were absent from the country for three years in a row lost their residence rights, and Indians who had entered the country illegally, mostly at the time of the Second Anglo-Boer War, were disregarded. Families of those disregarded were not allowed to join them and the Act also established a scheme of voluntary repatriation of South African Indians to India. The Bill became an Act on 5 July of the same year and thousands of Indians were sent back to India.

23 June 1927 saw Indians in the Northern Districts Act passed, which stipulated that Transvaal laws were to be applied to Indians in Utrecht, Vryheid, and Paulpietersburg. Restrictions were placed on land purchase, trade and residence rights. The Riotous Assembly Act warned of deportation of those Indians who agitated against the various restrictions. On 5 July 1927 the Nationality and Flag Act denied Indians the right to become citizens of South Africa. In 1930 the Transvaal Asiatic Land Tenure (Amendment) Bill was introduced and proposed segregation through the relocation of Indians to designated areas. The Women’s Enfranchisement Act also excluded Indian women from the vote.

Picture C: When women were allowed the franchise for the first time in South Africa Indian women, and all other “black” women, were excluded. Image source

Picture C: When women were allowed the franchise for the first time in South Africa Indian women, and all other “black” women, were excluded. Image source

In 1931 the Asiatic Immigration Amendment Act required that Indians prove they had legal status. In 1937 the Act was amended to deprive children of South African Indian parents the same rights as their parents. The Transvaal Asiatic Land Tenure (Amendment) Act of 1932, and its subsequent amendments in 1934, 1935 and 1937, established compulsory segregation of Indians and also prevented Indians from employing white workers. The 1935 Slums Act was aimed at improving conditions in locations, but actually reallocated Indian property. The Marketing and Unbeneficial Land Occupation Act of 1937 prevented Indians from representing their communities on regulatory boards and on 22 February of the same year 3 more Bills were presented that, although applicable to all “non-whites”, had a serious effect on Indians.

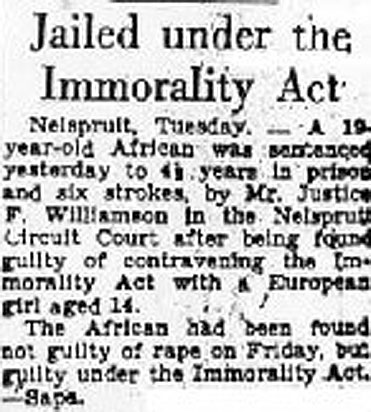

Although the Mixed Marriages Act was not passed at this time nuptials between whites and “non-whites” was severely frowned upon by the government and white society. The 1949 Immorality Act made it illegal to marry someone of another race.

Picture D: Bulawayo Chronicle, S. Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), 9 March 1960 Jailed under the Immorality Act. Note that the incident took place in South Africa, at Nelspruit. Image source

Picture D: Bulawayo Chronicle, S. Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), 9 March 1960 Jailed under the Immorality Act. Note that the incident took place in South Africa, at Nelspruit. Image source

Nelspruit, Tuesday.A 19-year-old African was sentenced yesterday to 4½ years in prison and six strokes, by Mr. Justice F. Williamson in the Nelspruit Circuit Court after being found guilty of contravening the Immorality Act with a European girl aged 14.

The African had been found not guilty of rape on Friday, but guilty under the Immorality Act.

The Mixed Marriages Bill aimed to prohibit marriages between Indians, whites and blacks, but was not passed. Instead a Mixed Marriages Commission was appointed. The Provincial Legislative Powers Extension Bill aimed to refuse trading licenses to “non-whites” who employed white people. The Transvaal Asiatic Land Bill denied the right of owning property to any white woman married to a “non-white”. In 1949 the Immorality Act followed on the Mixed Marriages Commission’s recommendations and the tenets of the proposed Mixed Marriages Bill were applied.

On 4 May 1938 the Asiatics (Transvaal Land and Trading) Bill was presented and in 1940 it became law. It provided for the protection of Indians in exempted areas and the issuing of certificates for trading licences to be authorized by the Minister of Interior. Indians were not allowed to appoint nominees to buy land and obtain trading licences on their behalf.

Due to the entrance of Indians into white areas, particularly as a threat to white businesses, the Trading and Occupation of Land Restriction Act No 35 of 1943, more commonly know as the Pegging Act, was passed in May. This Act provided for official control of property transactions between whites and Indians, due to the ‘penetration’ of Indians in predominantly white areas. In response to this treatment, the Indian government’s Central Legislative Assembly passed the Indian Reciprocity Act in New Delhi. It imposed the same restrictions on South African whites in India as those on Indians living in South Africa.

The Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act of 1946, or Ghetto Act, replaced the Pegging Act and was more specific concerning property transactions between whites and Indians. Indian people could only purchase land in the Transvaal and Natal, in specially defined areas. They could purchase and occupy such land, but could only sell the land under permit. The effect of this Act was that Indian property owners could not exercise rights of ownership over their properties and they could only lease land from whites on condition that the leased land would be used for business purposes only.

Organisations like the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), theNatal Indian Congress (NIC) and the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC) were formed to protect the interests of the Indian community in South Africa, specifically as a result of the anti-Indian legislation passed in the 1900s. The Indian community also protested segregationist policies through passive resistance.

Learning Outcomes: Communicate and present information reliably and accurately in writing.

Ability to work independently, formulating questions and gathering, analysing and interpreting relevant evidence to answer questions.

Synthesise information about the past and develop, sustain and defend an independent line of historical argument.