A. The Mineral Revolution ↵

In this section we will briefly discuss the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand and the Gold Rush. We will also discuss how the mining industry developed and how the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand impacted the area and all of its inhabitants. These impacts are important to understand as it gives one an insight of how some economic, social and political divisions were created and how this impacted the future generations.

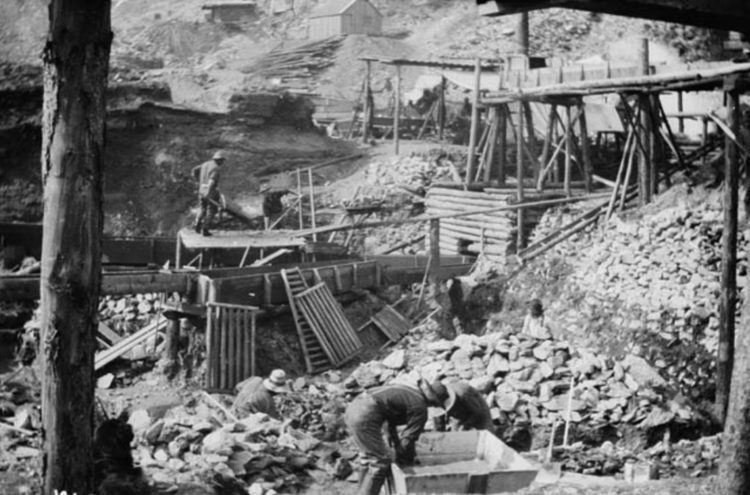

An Image depicting the Witwatersrand after the gold rush in South Africa in the 1880’s. Image Source (Accessed on 18 November 2020).

An Image depicting the Witwatersrand after the gold rush in South Africa in the 1880’s. Image Source (Accessed on 18 November 2020).

This Section is divided into the following discussion points:

- Discovery of Gold in the Witwatersrand

- The Development of the Mining Industry

- Foreign Investors and Mining Companies

- Deep Level Mining

- Impact of the Discovery

- Urbanization

- The Migrant Labour System

- Emergence of Classes

- The South African War

1. Discovery of Gold in the Witwatersrand:

During the late 19th century, various gold strikes (discovery of gold) occurred in areas in America, Australia, Asia and southern Africa.[1] However, the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand in 1886 was arguably one of the most significant discoveries as it supplied a great portion of the World’s gold in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[2] The first gold reef in the Witwatersrand was discovered by a man called George Harrison.[3] Harrison was travelling between a farm called Wilgespruit and a farm called Langlaagte to visit a friend, George Walker. On his way, Harrison found an outcrop of rock and after crushing the rock, he discovered a “tail of gold”.[4] This outcrop turned out to be a part of the reef that was later called the “Main Reef” and turned out to set off the beginning of the South African “Gold Rush” in 1886.[5] The gold fields in the Transvaal colony and surrounding area was the “largest single producer of gold in the world”.[6]

2. The Development of the Mining Industry

2.1 Foreign Investors and Mining Companies

When speaking about investment and capital surrounding the early gold-mining industry of Johannesburg, it is important to keep in mind that the world’s largest source of diamonds was discovered in Kimberley in 1866. This event set off the ‘diamond rush’ of South African in the 1870’s and meant that a mass number of diggers and investors were already attracted to the northern parts of South Africa. A prime example of an investor is De Beers South Africa, which was owned by Cecil John Rhodes and became the largest diamond producer and distributor in the world.[7] Furthermore, there were large coal deposits in Natal (which at the time, was one of the neighboring colonies of the Transvaal). Consequently, the fact that the discovery of gold and diamonds happened so narrowly apart, as well as the added availability of large coal deposits in neighboring areas, meant that there was an increasing economic and politic interest in these areas.[8]

The fact that diamonds were discovered only a decade before gold, also meant that there were working structures already in place that could support the knowledge, skill and investment required to manage and develop successful mining companies. For example, when news reached Cecil John Rhodes in Kimberley in July 1886, other diamond investors decided to diversify their funds and invest in the gold mining industry as well. Consequently, the first large gold mining company was formed in September 1886 and by 1888 there were approximately forty-four companies in the gold mining industry.[9] By 1899 there was approximately £75 millions of foreign investment.[10]

2.2 Deep-Level Mining

When the larger gold reefs were first discovered, it was thought that the gold-bearing conglomerates were relatively shallow and close to the surface. However, there was a sudden realization that these conglomerates sunk deep below the Rand’s surface.[11] Although some companies decided to continue mining the shallower outcrops, it became evident that the production and great turn-over resided with the deep-level mining projects.[12] These deep-mining companies required a large sum of investment as they required shafts, machinery and explosives to access the gold in the rocks. Interestingly, these companies also had to use certain chemicals to treat the gold out of the stone.[13]

3. Impact of the Discovery of Gold in the Witwatersrand:

The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand occurred more than a decade after the discovery of diamond in Kimberley in 1870. This was also the largest source of diamonds in the world at the time.[14] The discovery of gold also went hand-in-hand with the discovery of large coal deposits in the Natal colony, consequently setting off a “tripartite” discovery of resources which would eventually impacted the entire political, economic and social organization of South Africa.[15] Some of these impacts will be briefly discussed in the sub-sections below.

3.1 Urbanization and the Beginning of the City of Johannesburg

Before the major gold reefs was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886, there were approximately only 600 white farmers in the region.[16] However, the discovery sparked a mass migration of thousands of young men and within less than a year after the discovery approximately 7000 people were in the region.[17] Approximately a decade after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, 75 000 citizens from the United Kingdom immigrated to South Africa.[18] This number also includes numerous other tented mining camps that sprung up in proximity to other discoveries and sources of small bodies of water.[19] For example, in the Eastern side of the area small mines (followed by small settlements) started developing, leading to the further development of areas such as Springs, Brakpan and Benoni. Similarly, in the Western parts of ‘the Rand’ mining towns such as Roodepoort, Krugersdorp and Randfontein developed.[20] These smaller satellites (smaller cluster of towns) started merging into bigger areas (conurbations), which eventually led to the foundation of the City of Johannesburg on 4 October 1886.[21] This gold rush led to an absolute influx of people including gold diggers, mining-capitalists and prospectors – leading to Johannesburg quickly becoming one of the youngest major cities in the world and the only major city that was not in close proximity to a large body of water.[22]

The City of Johannesburg in the 1890’s. Image Source

The City of Johannesburg in the 1890’s. Image Source

3.2 The Migrant Labour System

The workers that flocked to the Witwatersrand were predominantly from rural areas and were classified as “temporary workers”.[23] They were regarded as “temporary workers” because the Political and Mining authorities of southern Africa created a labour system that focused on bringing cheaper labour from rural areas in southern Africa.[24] These workers came from various areas all over Africa which included: areas within the South African borders, men from independent territories such as Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland and then men who were from other countries such as Mozambique, Angola, Zambia and Tanzania.[25] This Migrant Labour System can be classified as a rotary system that meant that workers were employed for 18 month contracts and had no certainty of whether their contracts would be extended or not – hence why they were referred to as temporary workers.[26] After their 18 months expired, these workers had to migrate back to their areas of origin. These workers were convinced to take mining jobs because they had to pay “hut tax” that was enforced in 1884 and at this time mining was the most ‘stable’ source of income as the rural lands were relatively unproductive compared to other areas that were reserved for the ‘Europeans’.[27]

The Witwatersrand Labour Organization and the Native Recruiting Corporation

This system was officially implemented as early as 1900 when the recruitment Centre, “The Witwatersrand Labour Organization” (WNLA) was authorized to recruit workers from various rural areas.[28] The WNLA was especially used during the remainder of the South African War. The South African War had an interesting impact on the Migrant Labour cycle, as it caused the near shutdown of most mines which in return meant that thousands of young black men found themselves jobless in a foreign country and were forced to return to their homes.[29] Consequently, the labour shortage meant that the WNLA had to find other ways to supply Mining Companies with workers. Therefore, in 1904 a Chinese Immigrant Labour system was introduced, but was short-lived as by 1910 the last Chinese worker left the country.[30] Another recruiting agency, the “Native Recruitment Corporation” (NRC), was started in 1912.[31] It is worth mentioning that in 1977 these two recruitment agencies merged to form the “Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA), which is currently responsible for recruiting South African mine workers.[32]

Reasons for the Migrant Labour System

There are a few reasons why this Migrant Labour System was implemented by both the Government and the Mining Companies. Firstly, permanent residence was prohibited by the government as they aspired to keep the races separate.[33] Therefore, most workers were simply placed in informal camps that could easily be separated by race. This method of separation is regarded as a significant front-runner of the regulations and policies that were later implemented in the Apartheid years.[34] Secondly, the Mining Companies also benefited greatly from this system as they were absolved from providing long-term care for workers and therefore, sparing costs and capitalizing on the circular migrant labour system.[35] Unfortunately this meant that thousands of mine-workers passed away from diseases such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and “diarrheal diseases”.[36]

Impact of the Migrant Labour System

The Migrant Labour System implemented on the gold mines had various significant impacts on the development and structure of South Africa. One of the main impacts was that this Labour System could be regarded as a forerunner for Apartheid. The Labour System made it incredibly easy to keep races apart and to enforce segregation on various groups. Furthermore, by only temporarily allowing non-white races to enter “white areas” most black South Africans were forced to remain in a rural-based economic position.[37] Consequently, a deep Economic Class structure developed due to the Migrant Labour System. This will be discussed in more detail below.

The Migrant Labour System also had a profound effect on certain social aspects and dynamics of the mine workers. For example, most of these men (of all races) were usually forced to live in single-sex hostels and were only able to visit their families on certain occasions.[38] Women were left to till the farms and raise their families alone. Furthermore, because there were very few women on the mining properties, a significant amount of men turned to the use of prostitution and in many cases turned to alcohol and substance abuse.[39]

The Maximum Average Wage System

As briefly, discussed above, the Migrant Labour System played a significant role on the development and systems put in place by the Gold Mining Companies and Chamber of Mines – especially in the sense that it dictated most of the profit and income that could be made off of mining gold. Therefore, in 1913 the state and the Chamber of Mines developed and enforced a system that prohibited mining companies from increasing their wages in order to “lure workers away” from other companies.[40] This meant that family dynamics were significantly broken up and men became relatively irrelevant on the rural lands.[41]

3.3 Emergence of Classes

Capitalists:

The “Capitalist” Class is also referred to as the “entrepreneurial” class. This class predominantly consisted of the Uitlanders that migrated from Britain.[42] These entrepreneurs mostly consisted of Uitlanders because most of the Boers or Afrikaaners did not have the capital or knowledge to invest into the gold mining industry at the time.[43] This was significantly due to the effects of the South African War. The Scorched Earth Policy and Concentration Camp systems (which will be discussed in much more detail in the article below) implemented by British officials meant that the Boers did not have the financial stability to become big investors post-war. Many of them Afrikaaners employed as semi-skilled workers.

The Uitlanders that invested into the diamond mining industry and gold mining industry were referred to as the Randlords. These Randlords controlled most of the holding companies and funding that went into deep-level gold mining as it required large sums of capital.[44] As briefly mentioned above, deep-level mining required a large sum of funds because provisions such as dynamite and chemicals were used to access the ore from the stone.[45] Consequently, from 1886 to 1895 there was approximately 15 000 was invested into the Rand by these Randlords.[46] These entrepreneurs predominantly settled in Doornfontein, a wealthy suburb in Johannesburg.

Middle Class:

The ‘Middle Class’ consisted if the mining specialists and semi-skilled miners. As mentioned above, the semi-skilled miners were usually of Afrikaaner demographic. This was also not by accident; these positions were reserved for white South Africans. Because the Afrikaaners did not necessarily have the capital to fall in the ‘Entrepreneural’ category or had the skills to be occupy specialist categories, the skilled job opportunities were reserved for the white Afrikaaners. This was officially enforced by legislation known as “Job Reserveation’.[47]

The Afrikaaners came from rural farms, where some of them also spoke languages such isiZulu and seTswana which enabled a communication link between the Mining Capitalists and the ‘unskilled labourers’.[48] The skilled-labourers were permitted to stay in the white housed areas near the mines.

Mineworkers:

The mineworkers were classified as the ‘unskilled’ class and consisted of the black Africans that were recruited by organizations such as WNLA and NRC. These mine workers were required to attain the gold from the reefs that were situated thousands of meters into the earth.[49] These labourers were temporarily housed in same-sex hostels on the mining the mining properties.[50] As briefly mentioned above, these miners were subjected to a Maximum Wage System which meant that these miners only earned a certain salary with no hopes of earning more. Consequently, these workers remained in a lower economic standing than that of the English and Afrikaans-speaking white South Africans.

3.4 The South African War

Before discussing how the discovery of gold led to the outbreak of the South African War, it is extremely important to note that there are various causes for the South African War. These causes are discussed in more detail in the article below. However, for the sake of discussing the mineral revolution, it is important to understand how the discovery of gold led to one of the biggest wars in Southern African History. In a broader sense the outbreak of the war was caused due to increasing tension between the independent Boer States (the Transvaal and the Orange Free State) and the British Colonial Powers. One of the causes of this tension was the Transvaal government’s policies concerning Uitlander (predominantly English-speaking prospectors in the Transvaal) franchise.[51] It is important to take note that the Witwatersrand is located in the Transvaal, which at the time was one of the Boer Independent Republics. Although the policy surrounding franchise affected only a few of the Uitlanders, as they were simply in the Transvaal to mine for gold, the British officials felt it necessary to change the policy in the hope of achieving of a long-term goal – which was to gain more political control over the Transvaal and it’s gold minds and neighbouring diamond mines. For a more detailed explanation as well as causes, please refer to the sub-sections below.

B. The South African War (1899-1902) ↵

An image depicting the siege of Ladysmith in 1900 that occurred during the South African War (1899-1902). Image Source

An image depicting the siege of Ladysmith in 1900 that occurred during the South African War (1899-1902). Image Source

In this Article we will discuss the following:

- The Build-up to the South African War (1899-1902)

- The South African War (1899-1902) and its various phases

- The Scorched Earth Policy

- The Concentration Camps used during the War by the British

- The Role and Experience of Black South Africans during the War

- The End of the War and its Peace Negotiations

1. The Build-up to the South African War (1899-1902):

When discussing the build-up to the South African War (1899-1902), it is important to understand that there were various causes that led to the outbreak of the war. Some of these occurrences or causes occurred in the first few decades of the 19th century. Furthermore, these causes are still debated today, much like they were debated throughout the South African War itself.[52] It is in this regard that one should understand that it is beneficial to note that the conflict between the British and the Boers started well before the outbreak of the South African War of 1899-1902 and that one should have a brief background of the general relationship and occurrences between the British and the Boers since the start of the 19th century. Therefore, this conflict, as well as the factors leading up to the war, will briefly be discussed in the article below.

Early Conflict between the British Settlers and the Dutch-Speaking Farmers:

As briefly mentioned above, the conflict between the Boers and the British started well before the South African War. This conflict started shortly after circa 1795 when the British arrived in the Cape Colony in southern Africa and started to colonize the area.[53] When the British started to colonize, expand their influence in the area and implement British rule, the area was already predominantly inhabited by Dutch-speaking farmers.[54] Consequently, increasing tension occurred between the rural descendants of the Dutch Settlers and the British rules implemented in the Cape Colony.[55] Tension significantly rose due to the gradual forced anglicization (changing of spoken or written elements of another language to English) of the Colony, the gradual emancipation of slaves that occurred in the 1830’s and the need for independence from the British due to fundamental divergence between the two groups.[56] Therefore, in the attempts to gain independence from British Rule in the Cape Colony, approximately 14 000 Boers left in a series of groups (with an almost equal number of mix-raced dependents) and trekked to the interior of southern Africa in what is called the Great Trek.[57]

As the Voortrekkers (Dutch-speaking ‘pioneers’ that participating in the Great Trek) started making their way to the interior of southern Africa and crossing the Orange River, they started to divide into various groups with different destinations and ideals. One group of Voortrekkers settled in Natal, but were forced to re-join the other Voortrekkers after the British annexation of Natal in 1843.[58] The other two groups settled and established the independent Boer Republics of Transvaal (which was known as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republic) and the Orange Free State in 1852 and 1854, respectively.[59] These two establishments of the two independent republics was recognized by Great Britain in said years at the Sand River and Bloemfontein conventions respectively.[60] It is also after the establishment of the Republics where the word “Boers” was significantly used to refer to the Dutch-speaking farmers that settled in the two republics.[61]

For several years, the Boers were able to keep relative independence from British Rule in the Cape Colony. However, with the discovery of diamonds in the late 1860’s, the British started to expand their influence and control into the interior of southern Africa with the annexation of Basutoland in 1868.[62] Furthermore, the 4th Earl of Carnarvon, Henry Herbert (who was also appointed the Secretary of State for the Colonies), along with the British Government wanted to form a confederation of all British colonies, independent Boer Republics and all independent African groups in southern Africa under British rule in a surge for neo-imperialism.[63] With this aspect in mind, it should also be mentioned that the Boer Republic in the Transvaal was relatively politically and economically unstable. For example, the war between the Boers and the Pedi in North-Eastern Transvaal caused extremely high, and in many cases unaffordable, taxes that the burgers (Boer people) could not pay.[64]

Therefore, when Sir Theophilus Shepstone and 25 supporting British men arrived in the Transvaal on 22 January 1877, they managed to eventually annex the Transvaal on 12 April 1877 without enforcing any aggressive action.[65] However, although the annexation of the Transvaal was initially met with non-violence from the Boers, the majority of Boer were dissatisfied and attempting to resort back to an independent republic. This dissatisfaction grew and after various attempts and pleas to remain an independent republic, in November 1880 the first open conflict between the Boers and the British occurred in Potchefstroom – leading to the almost inevitable, Anglo-Boer War of 1880-1881 (or also known as, the Transvaal Rebellion).

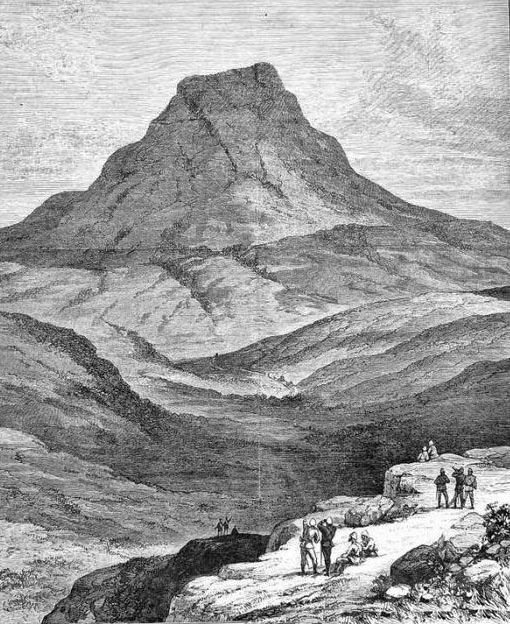

An image depicting British soldiers under Majuba Hill before battle. Image Source

An image depicting British soldiers under Majuba Hill before battle. Image Source

The First Anglo-Boer War (1880-1881)

The first open conflict that occurred between the British and the Boers in November 1880 that set off the beginning of the Transvaal Rebellion, was due to P.L. Bezuidenhout, refusing to pay “extra” taxes on his wagon as he claimed that he already paid taxes to the British colonial office.[66] This act of refusal caused the British to confiscate Bezuidenhout’s wagon and decided to auction the wagon off.[67] The auctioning of the wagon was put to an end when a group of Boers rebelled and claimed the vehicle by dragging it away and returning it to Bezuidenhout. Following the event, the British requested that the 58th Regiment return to the Transvaal to depict a sense that rebellion would not be tolerated.[68] Unfortunately for the British in the Transvaal, the majority of British militant aid was heavily preoccupied by the Cape Colony with the outbreak of the Gun War between British Colonialists and Basutoland (now Lesotho, who gained independence from the British crown in 1966).[69]

On 8 December 1880, approximately 10 000 Boers gathered at Paardekraal, near Krugersdorp where a triumvirate of leaders; Paul Kruger, Piet Joubert and M. W. Pretorius were appointed. On 13 December 1880 the leaders proclaimed the restoration of the Transvaal Republic and three days later raised their Vierkleur flag at Heidelberg, thus rejecting British authority.[70] Thereafter, four significant battles and sieges took place during the First Anglo-Boer War. The Boers issued terms of a truce on 14 March 1881 and on 30 March they received confirmation that it had been accepted. After peace had been negotiated a British royal commission was appointed to draw up the Transvaal’s status and new borders. These decisions were confirmed and formalized at the Pretoria Convention that took place on 3 August 1881.[71] This convention meant that although the Transvaal was to be an Independent Republic, the Transvaal would be kept a state under British suzerainty (which means that Britain retained some control over the foreign affairs and internal legislation of the ‘independent’ Boer Republic.[72] These conditions were deemed unacceptable by the Boers and therefore, in 1883 the new President of the Transvaal, Paul Kruger, left for London to review the initial terms of the Pretoria Convention.[73]

Consequently, in 1884 the London Convention was signed. The Transvaal was given a new western border and adopted the name of the Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek (ZAR). Although the word suzerainty did not appear in the London Convention, the ZAR still had to get permission from the British government for any treaty entered into with any other country other than the Orange Free State. The Boers saw this as a way for the British government to interfere in Transvaal affairs and this led to tension between Britain and ZAR.[74] It is important to note that the word “suzerainty” is significantly important when discussing the reasons for the outbreak of the South African War of 1899. This is mainly due to the conflict that will increase between the British and the Boers after the discovery of gold in 1886.

The Discovery of Gold in 1886:

After the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886, the Transvaal became a significant political and economic threat to British and their fight for the expansion of supremacy in southern Africa.[75] This is mainly due to the Transvaal-government’s policies concerning the accessibility to the newly found goldfields. For example, in 1890 the Transvaal’s government, led by President Kruger, decided to restrict the franchise of those who were considered Uitlanders (predominantly English-speaking prospectors in the Transvaal).[76] Consequently, only citizens who have stayed in the Transvaal for 14 years were able to vote in upcoming presidential and Volksraad elections. Although, this effected very few Uitlanders (as they were only interested in access to the gold mines), this decision increased negative sentiments between the British and the Transvaal.[77] Furthermore, the Transvaal’s government implemented various concessions on the accessibility of mining activities, which led to increasing conflict between the British and the Transvaal.

One of the biggest wedges between the two groups, was the decision of the Transvaal government to increase rates on the part of the newly completed railway that ran through the Transvaal’s territory.[78] The British answered this demonstration by transporting goods to the Vaal River and then using wagons to the Transvaal in order to avoid paying taxes. Consequently, the Transvaal blocked access to their territory by closing the drifts.[79] In addition to the Drift crisis, the Kruger government had been putting pressure on the mining companies in the form of taxes, and they maintained monopolies over items such as the dynamite needed for deep-level blasting.[80] This caused British businessman and imperialist, Cecil John Rhodes, and his associate, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, to begin planning an uprising of Uitlanders in Johannesburg, and the Reform Movement in an attempt to overthrow the government by taking up arms.[81] Joseph Chamberlain (British statesman, colonial administrator and politician) also played a significant role in the conspiracy to overthrow the Boer government with an uprising as he was in communication with Rhodes during the planning of the uprising.[82] This uprising is known as the Jameson Raid and plays an extremely important role in the build-up to the South African War.

A cartoon from Punch magazine that was published in 1892. The cartoon depicts Cecil John Rhodes stretching over Africa and symbolizing a degree of controlImage Source

The Jameson Raid:

The raid was launched on 29 December 1895, when Jameson and armed forces crossed the border from Bechuanaland (Botswana). Jameson, however, had been too hasty. Earlier, while Jameson waited on the border, the Uitlander leaders in Johannesburg were arguing among themselves about the kind of government to be put into place after the invasion. Many of the Uitlanders had no interest in violent uprising. Consequently, Rhodes decided to call off the raid, but by that time it was too late as Jameson and his party had already crossed into the Transvaal. Communication was lacking and plans were botched when all telegraph lines were not cut as had been planned. Consequently, the Boers received warning of the attack and knew where to find Jameson’s troops before they reached Johannesburg. Jameson was forced to surrender on 2 January 1896 at Doornkop near Krugersdorp. The raid had been a failure.[83]

The prisoners were handed over to their own government and the Uitlander leaders who had been part of the plot were put to trial in Johannesburg. Some of them were condemned to death, but the sentences were later reduced to large fines. Rhodes was forced to resign as the premier of the Cape Colony and the political problems between Afrikaans and English-speaking people became worse than ever in the colony. Although the British Imperial officials have been discussing the eventual overthrow of the Transvaal Government well before the events of the Jameson Raid, the Jameson Raid made it overtly (openly) clear of British intentions and sentiments towards the Boer Republics.[84] It is important to understand the dynamics between British and Boer as it gives one an important perspective of the build-up to the South African War.

Opposing sympathies from Britain:

After the occurrences of the Jameson Raid, Chamberlain began to openly voice his frustrations over the Boer control of the Transvaal and the possible loss of British supremacy in the northern parts of southern Africa.[85] Alongside this, there was a separation in Britain between those who were sympathetic of the idea of an independent Boer State and Nation and those who supported the idea of a war between Britain and the Boers to secure British imperial power over southern Africa.[86] To gain a better understanding of the opposing sides, one can used the petitions that were signed during this time as an example. In 1899, 21 000 Uitlanders signed a petition against Kruger’s rule in the Transvaal. This petition was countered by 23 000 signatures from Uitlanders who were in support of Kruger and a non-war resolution.[87] With this in mind, it becomes evident that there was a clear faction between those who wanted to get rid of Boer rule by means of a war and those who did not want a war and were content with Boer rule over the Transvaal.

An Ultimatum:

By September, Chamberlain had persuaded the British cabinet to accept the prospect of war. He drafted an ultimatum and reinforcements sailed for South Africa. Chamberlain increased the number of British troops stationed in South Africa. By October 1899 20,000 troops were stationed in Natal and the Cape, and more troops were on the way.[88] On 9 October an ultimatum was handed over to a British agent that stated that the British were to remove their troops that were stationed at the Transvaal border.[89] However, from a British perspective, because the Boers refused to grant franchise to the Uitlanders nor granting civil rights to the African Natives;[90] the British continued to build up forces and on 11 October the British rejected the ultimatum as presented by the Boers and war was declared.

2. The South African War (1899-1902) and its phases

A Brief Overview of the War

The South African War occurred from 11 October to 31 May 1902. The war is more appropriately referred to as the “South African War” instead of the “Second Anglo-Boer War” because the war’s participants not only included British and Boer soldiers, but also thousands of black South Africans, as well as thousands of soldiers from British contingents such as Canada, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand. The South African War was also known as one of the largest wars of its time as it featured approximately 500 000 British soldiers, 88 000 Boers, approximately 10 000 black men accompanying the Boers and approximately 100 000 black men accompanied the British during the war.[91]

The war also represented a foreshadowing of what modern warfare in the 20th century would look like. For example, both the Boers and the British made use of modern weaponry such as machine guns (Maxine gun), quick-firing rifles with magazines and new types of explosive with a wider range of damage (lyddite).[92] The war is also significantly known for the Boer’s method of warfare, namely “guerrilla warfare”, which is to become a key method of warfare in other wars such as the First World War and Vietnam War.[93] The war is also significantly known for the British’s use of concentration camps to imprison thousands of Boer civilians (mainly women and children), as well as thousands of black South Africans. These topics will be discussed in more detail throughout this article.

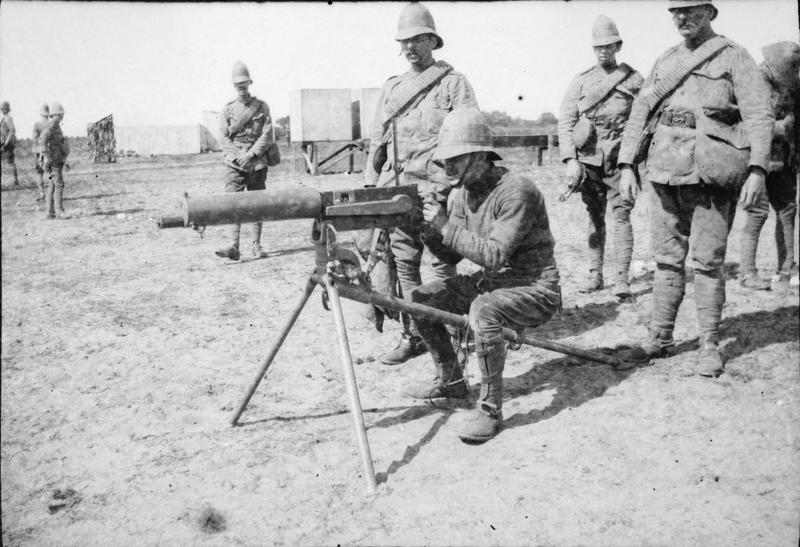

A photograph of a British soldier using a Maxine Gun during the South African War (1899-1902). Image Source

A photograph of a British soldier using a Maxine Gun during the South African War (1899-1902). Image Source

The Phases of the War

This image shows how the three phases of the South African War was divided. Image Source

This image shows how the three phases of the South African War was divided. Image Source

- The Boer Offensive:

The South African War consisted of three main phases. The first phase is called the “Boer Offensive” and is characterized by the success of Boer soldiers with their sudden and unexpected offensives against the British soldiers.[94] These successful sieges against the British occurred in Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley and later at Stormberg, Magersfontein, Colenso and Spionkop – which marked a week that the British referred to as “Black Week” (10 to 15 December 1899).[95] The victories over the British soldiers during “Black Week” marks a significant turning point in the trajectory of the war, as these ‘humiliation’ defeats (as British media portrayed it) greatly influenced the British’s decision to replace General Buller with Major-General Lord Kitchener on 16 December 1889.[96] This factor is significant as Kitchener played a pivotal role in deciding to use the Scorched Earth Policy and Concentration Camps in the attempt to secure victory over the Boers.

- The British Offensive:

After “Black Week” the British decided to send for extensive reinforcements. The second phase of warfare is called “The British Offensive” and is characterized by the British success over the Boer soldiers. On 10 January 1890 thousands of British soldiers, alongside Lord Kitchener and Lord Robert arrived in the Cape Colony.[97] These imperial troops eventually relieved towns such as Ladysmith and Kimberley (freeing Joseph Chamberlain who was trapped in siege in Kimberley for approximately 124 days) in February and Mafeking in May.[98] Furthermore, on 13 March Lord Roberts occupied Bloemfontein and formally annexed the Orange Free State by renaming it the Orange River Colony.[99] On the 31 May, the British entered Johannesburg and managed to conquer Pretoria on 5 June. The Transvaal was officially annexed by the British Crown and British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain announced that “the war is over”.[100] Unfortunately, this was far from the truth and the war would still continue for almost two years.

- Guerrilla Warfare:

After the annexation of Bloemfontein and Pretoria, approximately 14 000 Boers decided to lay down their arms and surrender to the British forces.[101] These Boers were referred to as hensoppers (surrenderers) by other Boers and were referred to as “protected Burghers” by the British. Another faction of these Boers was referred to as verraaiers and represented the faction of Boers who did not only give up their arms but decided to join the British troops in hopes of ending the war. The Boers that decided to not give up their arms, were referred to as the bittereinders (fighting to the bitter end). The bittereinders were led by Boer generals such as Louis Botha, Christiaan de Wet, Jan Smuts and Jacobus de la Ray.[102]

This phase is referred to as the Guerrilla Warfare phase because the bittereinders used tactics such as dividing into smaller groups and used these groups to capture supplies, sabotage British communication and transportation, as well as initiating various raids.[103] Because these groups were so small and familiar with the terrain, they were able to evade British capture. In response, Kitchener initially decided to place rolls of barbed wire and numerous blockhouses across the railways in the attempt to restrict the movement of the Boers.[104] Approximately, 8 000 blockhouses were set up.[105] However, when this method failed to put a stop to the bittereinders, Lord Roberts turned to the “Scorched Earth Policy”.

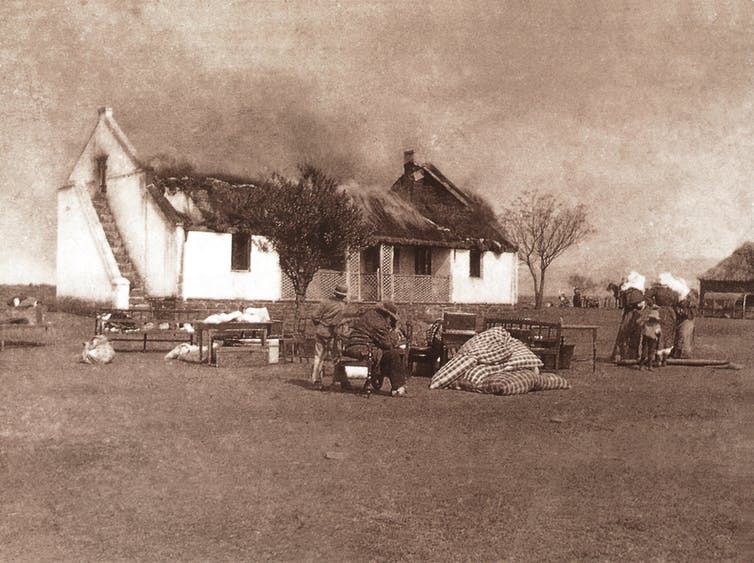

An image of a farmstead that was burnt down during the ‘scorched earth policy’ by British forces in the South African War.Image Source

An image of a farmstead that was burnt down during the ‘scorched earth policy’ by British forces in the South African War.Image Source

3. The Scorched Earth Policy

Lord Roberts issued a proclamation on 16 June 1900, stating that, for every attack on a railway line the closest homestead would be burnt down. This was the start of the scorched earth policy. When this didn’t work, Roberts issued another proclamation in September stating that all homesteads would be burnt in a radius of 16 km of any attack, and that all livestock would be killed or taken away and all crops destroyed. This policy was intensified dramatically when Lord Kitchener took over from Roberts as commander in November 1900. Homesteads and whole towns were burnt down even if there was no attack on any railway. In this way almost all Boer homesteads – about 30 000 in all – were razed to the ground and thousands of livestock killed. The two republics were entirely devastated.[106]

Meanwhile the Boer leaders were reorganizing their commandos after some major setbacks. One action was to remobilize the Boers who had laid down their arms. Roberts felt he should protect his oath takers and gather them in refugee camps. The first two were established in Bloemfontein and Pretoria in September 1900. But the scorched earth policy had led to more and more Boer women and children being left homeless. Roberts decided to bring them into the camps too. They were called the “undesirables” – families of Boers who were still on commando or already prisoners of war.[107] These camps are what is known as the concentration camps of the South African War.

4. The Concentration Camps

When Lord Kitchener took over from Lord Roberts, Kitchener decided to expand on Roberts’ concentration camp system. Kitchener did this so that the Boers who were still on commando (bittereinders) could not receive any supplies, food or weapons from the farms. Kitchener also hoped that these Boers would eventually surrender as they would be reunited with their families again.[108] Due to poor administration (low quality in food, unhygienic living conditions and inadequate medical care), approximately 28 000 Boer women and children died.[109] These deaths were a combination of malnutrition, illness and brute force. It is also very important to mention that there were also separate concentration camps for black South Africans (which will be discussed in detail in the following chapter), where approximately 20 000 black South Africans died.[110]

Towards the end of 1900, the poor conditions of the concentration camps started to reach the British public and especially the liberal party. This news also reached philanthropist Emily Hobhouse and drove her to attempt to find ways to relieve the Boer women and children in the British concentration camps.[111] Hobhouse decided to set up the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children, which was aimed to provide the Boer women and children with provisions such as food and clothing.[112] After visiting the concentration camps herself and witnessing first-hand the poor conditions in which the women and children were living, Hobhouse decided to advocate for better living conditions to the British administration at these camps. Unfortunately, the British were desperate in their attempts to end this costly war and Hobhouse’s requests were ignored or denied.

Hobhouse decided to travel back to Britain and advocate for the improvement of conditions in these concentration camps. Hobhouse reported to structures such as the liberal opposition of the British government, as well as other organizations.[113] Eventually, the British government decided to send Dame Millicent Garret Fawcett, the president of the National union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1897, to the concentration camps in July 1901.[114] After the members of this committee visited the concentration camps, they decided to send back a report to England in which they agreed with Hobhouse’s evaluation and recommended that the British administration drastically make improvements to the living conditions at the camp.[115]

5. The Role and Experience of Black South Africans during the War

As briefly mentioned throughout the article, the South African War was not only a war between the Boers and the British, but also a war where approximately 10 000 black men accompanying the Boers and approximately 100 000 black men accompanied the British during the war, where 10 000 were armed.[116] Except for the concentration camps for Boers there were also concentration camps for black South Africans where approximately 115 000 people were imprisoned by the British. It is also important to mention that the ‘scorched earth policy’ also led to the vast deplanement of thousands of black South Africans. It should also be mentioned that the war was initially intended to be a “white man’s war” where both the British and the Boers decided that they did not want to involve the black population.

Reasons for the initial intention of a “white man’s war”

The British believed that the Boers would be easily defeated and that any military collaboration from groups of Blacks would not be decisive in winning the war. In addition, it was commonly believed by both sides that the military methods of the Black people were more brutal than those of white people and that white women and children would not be shown mercy by Black soldiers. Another reason for not wanting Blacks to be given arms was the fear that this would increase the possibility of Black resistance to white control in the future.[117]

Republican law forbade the carrying of arms by Blacks, but because many Boers were pressed into service, they allowed their servants to carry arms. Black cooperation in the war enabled a larger number of whites to serve actively in war operations on both sides. According to the law of the Republics, all males between the ages of 16 and 60 were eligible for war service, and although the law did not refer to race it was generally applied to the white population only.[118]

Reasons for Black People Entering the South African War

- British Perspective:

It was estimated that about 100 000 Blacks were employed by the British army and more than 10 000 received arms. The British army used Black workers for carrying dispatches and messages, to take care of their horses and assist in the veterinary department. They also were used to do sanitary work and construct forts. Armed Black sentries guarded blockhouses and were used to raid Boer farms for cattle.

The British army also provided the Kgatla chief and Kgama of the Ngwato with 6000 and 3000 rounds of ammunition respectively, to defend the Bechuanaland Protectorate. In the Transkei, 4000 Mfengu and Thembu levies were assembled to ward off any attempt at invasion by the Boers or to suppress any Boer uprising. The Boer occupation of Kuruman was initially resisted by a small force of local Coloured and white policemen. In Mafeking, over 500 Blacks took part in the town's defence during the siege and 200 more enrolled as special constables in Hershel to discourage incursions into the area by Free State commandos. In Natal, the Zulu Native Police were armed with rifles and a number of them were mounted. However, after the war, Blacks who had served as scouts or fighting men were denied campaign medals which they were entitled to.

It is apparent that both sides would deny that armed Blacks served with them, each accusing the other of doing so, However, in April 1902, after much pressure, Lord Kitchener finally admitted that some 10 053 Black men were issued with arms by the British army. The Boers cited the arming of Blacks on the side of the British as one of the major reasons for discontinuing the war.

- Boer Perspective

Black people assisted at various levels. Most were assigned to the roles of wagon drivers or servants. Black people were also used to stand in on farms of Boers who were commandeered to the war. This is where many black people were largely affected by the ‘scorched earth policy’. Many were used as "agterryers" who would tend to chores at the camp or see to the horses. On the battlefield, the 'agterryer' would carry spare ammunition and spare rifles and even load up the rifles to the Boers. The Tswana people were conscripted by the Boers to help maintain the siege of Mafeking. Many armed Blacks and Coloureds also assisted during the siege of Ladysmith.

- Black South African Perspective

Black poverty was a major spur to enlistment in the British army. For many families, the war had disastrous consequences as it disrupted the migrant labour system, a development that deprived them of an income used to buy grain and pay taxes and rent. Also, the return of thousands of men to the rural areas increased the pressure on food resources in some already overpopulated districts of Natal, Zululand and the Transkei. In the Transvaal and Orange Free State Britain's scorched earth campaign destroyed the livelihoods of many thousands of black people.

Experiences of Black South Africans during the war

Many Black people were held in concentration camps around the country. The British created camps for Blacks from the start of the war. Entire townships and even mission stations were transferred into concentration camps. The men were forced into labour service and by the end of the war there were some 115 000 Blacks in 66 camps around the country.

Although very low, maintenance spent on white camps were a lot higher than that spent on the black camps due to the fact that black people had to build their own huts and even encouraged to grow their own food. Less than a third of Black interns were provided with rations. Black people were practically being starved to death in these camps. Black people were also not given adequate food and did not have formal medical care. Those in employment were forced to pay for their food. Water supplies were often contaminated, and the conditions under which they were housed were appalling, resulting in thousands of deaths from dysentery, typhoid and diarrhea. The death toll at the end of the war in the Black concentration camps was recorded as 14 154, but it is believed that the actual number was considerably higher.

6. Peace Negotiations and the End of the War

With the devastation as brought on by the ‘scorched earth policy’ and the concentration camp, many Boers wanted the war to end. However, when Britain offered the Boers and end to the war in March 1901, the Boers rejected the proposal as they were unwilling to give up their independence to the British colonialists.[119] With another year of devastation Boer leaders such as Louis Botha and Jan Smuts decided to go against the best wishes of most of the bittereinders and opted to sign the “Peace Treaty of Vereeniging” as set out by Lord Kitchener and Lord Milner on behalf of the British government.[120] Although the British wanted full control over the two Boer Republics, the General Smuts opted the British to agree over the basis of suzerainty[121] (Britain did not have full control over the Republics, but do have the authority over the foreign policies of the Boer Republics). The treaty therefore, promised Boer self-governance in exchange for efficient management of the gold mines. The treat also secured an alliance between both the British and the Boers against the black Africans in Southern Africa.[122] This treaty was signed on 31 May 1902.

For a look at the transcript and signatures of the Treaty of Vereeniging, please click on the following: the “Peace Treaty of Vereeniging”

C. The Union of South Africa ↵

Author Bruce Berry, “Governors-General of South Africa (1910 – 1961), Crwflags, (Uploaded: 2017), (Accessed: 9 November 2020) Image Source

The Union of South Africa was established on 31 May 1910 as an all-white parliament focused on enforcing repressive racial laws to solve the poor white problem caused by the South African War.[123] Diseases, droughts and the Scorched Earth Policy, which left over 30 000 Dutch farms burnt to the ground and impoverished after the South African War, were used as justification to establish a racist state.[124]

This following topic will discuss:

- The National convention of 1908

- The South African Act of 1909 and the denial of franchise to Black South Africans

- The launch of the Union in 1910.

National Convention 1908

The National convention started in Durban on 12 October 1908 to foster closer relations between the four colonies with regard to policies concerning labour, the relationship of between Britain and South Africa, education, fostering equality between Afrikaans/Dutch and English and the question of extending franchise to Black South Africans.[125] This convention can be considered the prelude to South Africa becoming a Union. All of the colonies that participated in this process were considered self-governing territories. Among the major debates at this convention was the question of whether the unification of the South African Colonies would take on the form of a union or a federation, as well as the economic system that would be implemented and the establishment of legislative procedures. Finally, this convention also discussed the apportioning of constitutional authority in such a way as to avoid a situation in which the political interests of one group would dominate the other. However, Britain failed to promote the enfranchisement of black South Africans, since they argued that it would not be adequate enough to further African interests as they believed their interests should rather be furthered through developing “native institutions”.[126] This convention in many regards constituted the foundation for the Union of South Africa, as many of the issues discussed and examined would form part of the laws of the eventual Union.

South Africa Act 1909 and the denial of franchise to Black South Africans

The South Africa Act of 1909 legalized the decisions made at the 1908 National Convention by the British Parliament. This Act encompassed the language policy and the denial of franchise to black South Africans. The passing of this act, however, was not made without opposition as the South African delegation known as the Schreiner mission was sent to Britain. [127] W.P. Schreiner, a former minister of the Cape and a lawyer together with J.T. Jabavu, a newspaper editor and Reverend Walter Rubusana, a Congregationalist minister, sent a Cape Coloured deputation and a Bantu deputation, pleading for the British Empire to confer the right to vote upon all South Africans and to invest more in promoting the rights of Africans.[128] The Schreiner mission was mainly concerned with the impact the unification of the colonies would have on empowering the Union parliament to remove the franchise from persons of colour.

In 1909 Lord Crewe, who became the new Colonial secretary met with the delegates of the four different colonies to discuss the drafted constitution for the Union of South Africa.[129] The drafted constitution was accepted with minor changes. However, even though the constitution was accepted the unification of the four colonies came with a few challenges. The process of forming Union was hampered, since smaller and less wealthy colonies feared that the larger and wealthier ones would dominate them. The Cape colony, in particular, feared that in a union, the other colonies would eliminate Black voters from the voters’ roll, and these voters were the electoral base for many Cape politicians.[130] Natal, on the other hand, wished to retain some of its independence, but eventually relented on this condition.

Finally, after drafting the Constitution, it was vital to decide who would be the new Prime Minister of the first government. Three statesmen were identified, namely Marthinus Steyn, the former president of the Orange Free State, John Merriman, who was the Cape Prime Minister at the time and Louis Botha, president of the Het Volk party in the Transvaal.[131] Louis Botha was finally elected as the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa who served from 1910 to 1919.[132]

Launch of Union 1910

On the 31 May 1910, exactly eight years after the Boers had made peace with the English through the Treaty of Vereeniging, South Africa became a Union. Despite the mistrust in the Boer camp, the Afrikaners, as they now became known, had negotiated and achieved self-determination.[133] The formation of the Union of South Africa changed the entire political landscape of South Africa.[134] The granting of self-governance to the different South African colonies encouraged closer economic ties and brought the vision of a unified South Africa closer to reality. The formation of the Union of South Africa was nothing short of a miracle since it unified the British and the Afrikaners despite the hatred, tensions and damage that the two South African Wars had inflicted on the psyche and landscape of the country. Previously, the Afrikaners tried to escape the British imperialism. The formation of Union was ideal for the Afrikaners, as shown in a letter from Jan Smuts to John X. Merriman in which he stated: “You know, with the Boers, United South Africa has always been a deeply felt political aspiration and it might profitably be substituted for the imperialism that imports Chinese, a foreign bureaucracy and foreign standing army.”[135] It must be admitted that the formation of the Union was a direct result of the Treaty of Vereeniging. By ignoring the wishes of the majority of the population, the formation of the Union of South Africa contributed to the political upheaval and turmoil that would engulf the country for the next eighty years.

Black response to the formation of the Union

The response of the African press to the formation of Union was one of undisguised hostility. Much effort was directed at stalling or changing the draft Act of the South African Union. But despite all efforts, the act was passed through the colonial parliaments.

In response to the South African National Convention, John Tengo Jabavu also convened the Cape Native Convention, which included a group of black delegates from the four provinces in Bloemfontein to oppose the draft of the South African Act.[136] Jabavu was an important Black politial leader, educationist, and journalist, and he played an important role in the establishment of what was to become the African National Congress.[137] The principle objection of this convention was that Britain would no longer be able to intervene on behalf of the native people and that the relationship between them and the Crown would be broken.

The attempt was doomed to fail, despite the fact that every politically conscious black person was against the terms and not the principal of the Union. The representatives of the National Convention and various colonial governments gave their support to the formation of the Union under terms that virtually ignored the Black population. Despite vocal objections to the terms, the establishment of the Union of South Africa went ahead.

The Formation of the ANC 1912

Preliminary drafts of the Union governments Natives’ Land Act were debated in 1911 and the Mines and Works Act was passed in 1911.[138] These laws and the formation of the Union were important factors leading to the formation of the South African Native National Congress on 8 January, 1912, in Bloemfontein, renamed the African National Congress in 1923. Land dispossession lies at the heart of South Africa’s history and heritage of inequity. The new ANC was created against the backdrop of massive deprivation of Africans’ right to own land.

To read more about the formation African National Congress in 1912 and the factors leading to the formation.

Although the Colonial Government passed many discriminatory laws against Blacks, the most severe, the 1913 Natives’ Land Act, codified those injustices by preserving the large majority of the Union’s land for the exclusive use of the white minority.[139] The Act effectively meant that access to land and other resources depended upon a person’s racial classification. As Sol Plaatje described the Act entailed that: “natives shall not enter into any agreement or transaction for the purchase, hire, or other acquisition from a person. other than a native, of any right, thereto, interest therein, or servitude there over.”[140] This legislation caused endemic overcrowding, extreme pressure on the land, and poverty.[141]

D. Sol Plaatje and the 1913 Land Act ↵

This topic discuses:

- Sol Plaatje and his role in fighting against the 1913 Natives Land Act

- The economic and social impact of the 1913 Natives Land Act

- How the 1913 Natives Land Act became the precursor to Apartheid legislation

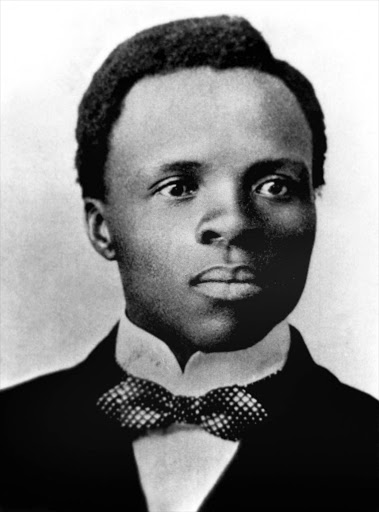

Blake Linder, “Today in History: Sol Plaatje died; Eight of his most profound quotes”, Roodepoort Record, (Uploaded: 19 June 2018), (Accessed: 8 September 2020) Image Source

Who was Sol Plaatje?

Solomon Tshekeisho Plaatje was born as a Tswana-speaker south of Mafeking in 1878.[142] He distinguished himself as an intelligent student and by the age of 16, when he started working at the Post Office, he achieved the highest mark for the clerical examination in the Cape Colony.[143] When Plaatje turned 21 he became an interpreter at the magistrate’s court where he enabled the British authority to communicate with Africans during the siege of Mafeking (1899 – 1900). As a court interpreter, Sol Plaatje could interpret eight different languages, which included Dutch, English, German and African vernaculars.[144] During this period Plaatje started writing diaries, recording what had happened during the siege of Mafeking. [145]

Thereafter, Plaatje became a journalist, establishing the first Setswana-English newspaper in 1901, Koranta ea Becoana (Newspaper of the Tswana) in Mafeking.[146] Approximately ten years later, Plaatje moved to Kimberly and established a new newspaper, called Tsala ea Becoana, meaning Becoana’s friend. In April 1913 Tsala ea Becoana was renamed to Tsala ea Batho, which is translated as meaning “Friend of the People”.[147] This title change occurred since Plaatje became aware of the national shift from tribalism to focusing on the nation.[148] Hw

In 1909 Plaatje wrote “Sekgoma – the Black Dreyfus”, an unpublished manuscript that showed his resentment for the British, who after the South Africa War, only gave enfranchisement to the white population.[149] In the 1910 Union of South Africa the Afrikaners controlled South Africa and Sol Plaatje was one of the few Africans who still had a parliamentary vote. This disenfranchisement of the black population caused Plaatje to become involved in “native congress” movement, which aimed to further the Africans in the country. In 1912 he became the first secretary general of the South African National Congress (SANNC), which was later renamed to the African National Congress (ANC).[150]

In 1913 the Land Act was introduced, which entailed that Africans could only own 7% of the land as they were prohibited from buying or hiring 93% of South Africa. According to the Land Act: “natives shall not enter into any agreement or transaction for the purchase, hire, or other acquisition from a person. other than a native, of any right, thereto, interest therein, or servitude there over.” [151] Africans were restricted to living in overpopulated reserves without basic human rights of owning land. This act was also introduced mid-winter and in response to this law, Sol Plaatje travelled by train and then on his bicycle to analyse the impact of the Act on black South Africans.[152] He describes how Africans were forced to choose between losing their ability to own cattle and farm independently but be able to remain tenants on a white man’s farm or to move, which Sol Plaatje described as a “native trek”, in the dead of winter. [153] These natives hoped to move to other farms, where they would be allowed to farm independently, but the Act prohibited white farmers from employing or leasing land to black South Africans. Their search for land and the “native trek” was in vain and resulted in the cattle owned by natives either dying or being sold. [154]

These conditions caused the SANNC resisting against the 1913 Land Act. In 1914 Sol Plaatje and national executives of the SANNC sent a delegation to the British crown.[155] Plaatje urged the queen to veto this law. However, with the start of the First World War, Britain chose not to undermine the Afrikaners legislation for the loyalty of the Afrikaners in the war and thus ignored the SANNC delegation.[156] While the rest of the SANNC members returned to South Africa, Plaatje remained in Britain, hoping to persuade the British crown to veto the Natives Land Act. He continued writing and in 1916 he published two short books named the “Sechuana Provebs” and the “Sechuana Reader” and a longer book titled “Native Life in South Africa.[157] Native Life in South Africa was written in response to the introduction of the Natives Land Act of 1913 and explained the impact of this law on Black South Africans.[158] The book illustrates how Africans were born as “pariah’s in the land of his birth” since Africans were treated as outcasts that had to be avoided and despises at all costs.[159]

In 1919, after the end of World War One, Plaatje returnd to south Africa to lead another delegation to England against the Natives Land Act.[160] These attempts against the Natives Land Act also proved unsuccessful. Thereafter, Plaatje again wrote another book, titled “The Mote and the Beam: An Epic on Sex-Relationship “twixt Black and White in British South Africa”. With the income generated from the sales of this book, Plaatje was able to travel to America for a lecture tour.[161] In 1921 an edited version of Native Life in South Africa, was published by the NAACP.[162] In 1923 Sol Plaatje returned to South Africa.[163]

During the 1920’s, Sol Plaatje became less involved in politics, since he promoted old black liberalism rather than the radicalism of the ANC. Thereafter, Plaatje focused on translating Shakespearean plays and writing historical novels, such as Mhundi (An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago).[164] In 1932 Plaatje died of pneumonia. At his funeral his daughter stated: “For here was one devoid of wealth but buried like a lord.”[165]

After Sol Plaatje’s death, his work still remained relevant and in 1972 his last literature pièce was published, namely the Mafeking diary he had written at the start of his career as an African interpreter. This diary was titled The Boer War Diary of Sol T. Plaatje: An African at Mafeking.[166]

Sol Plaatje played an active role in furthering the rights of Africans, by giving a voice to a silenced majority and making the Afrikaners and the British aware of the impact of their laws and treatment upon their fellow man.

The 1913 Natives Land Act

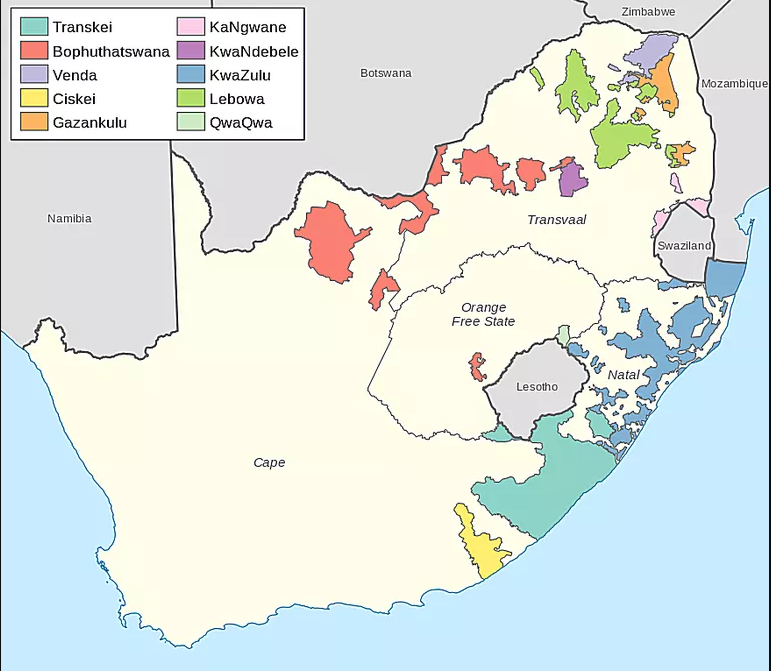

Alistair Boddy-Evans, “Pre-Apartheid Era Laws: Natives (or Black) Land Act No. 27 of 1913”, ThoughtCo. (Updated: 17 June 2018), (Accessed: 8 September 2020), Image Source

Alistair Boddy-Evans, “Pre-Apartheid Era Laws: Natives (or Black) Land Act No. 27 of 1913”, ThoughtCo. (Updated: 17 June 2018), (Accessed: 8 September 2020), Image Source

On 19 June, 1913 the Native Land Act was introduced which limited African land ownership to 7%.[167] According to this Act, Africans were not allowed to buy 93% of the land allocated to European settlers and were only allowed to occupy land owned by the settlers as employees. After the Act was approved, Africans were relocated to impoverished homelands and townships. This Act had a vital socio-economic impact on Africans, since they were forced to live in overpopulated and impoverished reserves, which forced many to look for employment far away from their homes to provide for their families.[168]

The Economic Impact of the Natives Land Act

- The Natives Land Act allowed Africans to only own 7% of the land in South Africa. Africans were denied access to landownership of 93% of the land.[169]

- Africans were also not allowed to lease land from White settlers.[170]

- The Act prohibited Africans from competing in the market as independent farmers since they could not buy fertile land from white settlers. [171]

- Sharecropping was declared illegal under the 1913 Land Act. Prior to the Act, white and African farmers could sow on the same farm on the basis of shares and split the profit.[172]

- Africans were forced to live in impoverished and overpopulated reserves, which forced them into servitude. [173]

- The land assigned to Africans were also placed in infertile farming grounds, which continued to impoverish them.[174] One of the commissioners in charge of dividing the ground between white settlers and Africans noted about the Kwelera-Maoiplaats region that it was: “poor soil with a steep and sour pasturage of so limited extent that only a Kaffir, with his limited requirements could be expected to exist upon such terms.” The commissioner thereafter recommended that these grounds be given to Africans.[175]

- The overpopulated reserves and already infertile grounds give to Africans limited their agricultural production and caused a rise in poverty amongst African farmers. [176]

- The Apartheid government also refused to give economic aid to the African reserves through loans. African farmers could not compete with the fertile ground nor the technological methods White farmers used.[177]

- The Natives Land Act contributed to a high poverty rate amongst Africans.[178] Africans, who were once independent farmers or sharecroppers lost their land and were no longer self-employed or able to compete in the market. The Act forced many Africans to leave their homes to search for work and ended up as workers on the diamond and gold mines.[179]

The Social Impact of the Natives Land Act

- The Natives Land Act enabled the apartheid government to move Africans to reserves, which caused racial segregation between Africans and white settlers.[180] This Act promoted the racist ideology that one race is superior to another through the visible divide it created between Africans and White settlers. The impoverished state of the reserves continued to reinforce the racist ideology that white settlers were better than their African counterparts.

- The construction of reserves also enabled the apartheid government to remove all rights of Black South Africans, since they aimed to create independent African governments who would be responsible for the governance and development of the reserves.[181] This decision did not truly promote African independence, but rather enabled the apartheid government to ignore the rights and needs of Africans in South Africa.

- African families were evicted from their homes and ancestral grounds and forced into reserves. African families were rendered destitute.[182] It was also illegal to give landless Africans a place to stay and one could be fined 100 pounds or be imprisoned for disobeying this law.[183]

- Africans were often forced to kill or sell their livestock, since they did not have enough land on which the animals could feed.[184]

- African families were also divided since the reserves grounds were overpopulated and infertile which forced family members to go work in the mining sector to provide for the family. [185]

Reactions to the 1913 Natives Land Act

- The SANNC was founded to oppose the 1913 Natives Land Act. [186]

- Sol Plaatje and members of the SANNC investigated the impact of the Natives Land Act and sent a delegation to Prime Minister, Louis Botha in 1914.

- This appeal failed and a few members of the SANNC, including Sol Plaatje left to Britain to ask for intervention. This attempt also failed.

- The SANNC continued to oppose the Act and established themselves as fighters against racial discrimination of Black South Africans. [187]

- Sol Plaatje wrote various books, such as Native Life in South Africa, and established newspapers to oppose the Act and make people aware of the social and economic impact of the Act.

The 1913 Natives Land Act: The Precursor to Apartheid

At the start of the nineteenth century the Union of South Africa’s legislation promoted racial segregation. In 1912 the Union of South Africa implemented the Irrigation and Conservation of Water Act (No.8), which limited access to water by giving white settlers riparian water rights. Riparian water rights dictate that people living close to water are prioritized and given more water.[188] The following year the Natives Land Act was introduced as one of the first acts that racially and spatially divided Africans and white settlers.[189] After the Natives Land Act was implemented, various other acts focused on promoting racial segregation was introduced, such as the Urban Areas Act (1923), the Natives and Land Trust Act (1936) and the Group Areas Act (1950). [190]

- Urban Areas Act (1923)

After the Native Land Act was accepted in parliament, the Union of South Africa saw a rising need to control the influx of Africans into the cities since the reserves were overpopulated with infertile ground for agricultural production causing many Africans to seek employment by white settlers in the cities.[191] This legislation enabled authorities to provide trading licences to African location residents and illegalized giving Africans freehold property rights. Africans could not be given permanent residency in the cities where they worked, since they were merely allowed to stay temporarily when their work was needed by the white settlers.[192] This influx control of Africans enabled the Union of South Africa to control the movement of Black South Africans through racist legislature. The Natives Land Act only set the stage for the start of many new racist policies, such as the implementation of the 1923 Natives Urban Areas Act (No.21).

- Natives and Land Trust Act (1936)

In 1936 the Natives and Land Trust Act was introduced, which extended the amount of land Africans could possess from 7% to 13%.[193] While this law minimally increased the amount of land Africans could own, it still promoted the same racist ideology of the 1913 Natives Land Act. Africans were still forbidden to hire or buy land outside of the reserves.[194] The Union of South Africa’s legislation continued to create an impoverished African class in South Africa, while economically and socially uplifting white settler.

- Group Areas Act (1950)

The 1950 Group Areas Act (No. 41) was implemented to continue creating racially divide between South Africans. According to this Act it was a criminal offence to own land in an area that was set aside for another race.[195] This act had a profound effect on furthering segregation since this law now included “coloureds” as a racial group that had to be separated from White South Africans. This law enabled the government to centralize control over racial segregation, while taking away the municipal autonomy of Africans.[196] The racist ideologies and laws of the Group Areas Act was easily enforced since the act continued to build on the ideas of separate development and native reserves which was introduced through the 1913 Natives Land Act.

- Natives Act (1952)

The 1952 Natives Act, otherwise called the Abolition of Passes, and Co-ordination of Documents Act forced Africans to wear passes to restrict their freedom of movement in the areas allocated to white settlers.[197]

The Natives Land Act of 1913 was the precursor to Apartheid as it set the stage for Hendrik Verwoerd’s homeland policies, the influx control of Africans through establishing pass laws through the Group Areas Act and forcibly removing Africans from their places of residence in the 1970’s and 1980’s.[198] The 1913 Land Act formed the basis for the following racist acts introduced and accepted in parliament, promoting separate development between races as well as a racial hierarchy in favour of the white man.

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by

Ilse Brookes, Amber Fox-Martin & Simone van der Colff

End Notes

[1] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 319.

[2] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 320.

[3] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 316.

[4] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 316.

[5] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 316.

[6] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 320.

[7] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica.: “De Beers S.A.” Encyclopaedia Britannica [online], Available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/De-Beers-SA (Accessed on 24 November 2020).

[8] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 321.

[9] D.W. Gilbert.: “The Economic Effects of the Gold Discoveries Upon South Africa: 1886-1910,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, (47), (4), p. 557.

[10] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica.: “Diamonds, Gold and Imperialist Intervention (1870-1902),” Encyclopaedia Britannica [online], Available at https://www.britannica.com/place/South-Africa/Gold-mining (Accessed on 24 November 2020).

[11] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 322.

[12] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 322.

[13] D.W. Gilbert.: “The Economic Effects of the Gold Discoveries Upon South Africa: 1886-1910,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, (47), (4), p. 556.

[14] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 321.

[15] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 321.

[16] S. Chibba.: “A History of Mining in South Africa,” South Africa [online], Available at https://www.southafrica.net/us/en/travel/article/a-history-of-mining-in-south-africa (Accessed on 24 November 2020).

[17] M.N. Lurie & B.G. Williams.: “Migration and Health in Southern Africa: 100 Years and still Circulating,” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, p. 35.

[18] P. Richardson & J.J. van Helten.: “The Development of the South African Gold-Mining Industry, 1895-1918,” The Economic history Review, (37), (3), p. 320.

[19] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 317.

[20] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 317.

[21] A. Turton, C. Schultz, H. Buckle, M. Kgomongoe, T. Malungani & M. Drackner.: “Gold Scorched Earth and Water: The Hydropolotics of Johannesburg,” Water Resources Development, (23), (2), June 2006, p. 317

[22] J.T. Campbell.: “Johannesburg,” Encyclopaedia Britannica [online], Available at https://www.britannica.com/place/Johannesburg-South-Africa (Accessed on 24 November 2020).

[23] M.N. Lurie & B.G. Williams.: “Migration and Health in Southern Africa: 100 Years and still Circulating,” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, p. 35.

[24] M.N. Lurie & B.G. Williams.: “Migration and Health in Southern Africa: 100 Years and still Circulating,” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, p. 35.

[25] J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan & E.Z. Chelkowska.: “A Century of Migrant Labour in the Gold Mines of South Africa,” The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, (1), p. 65.

[26] J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan & E.Z. Chelkowska.: “A Century of Migrant Labour in the Gold Mines of South Africa,” The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, (1), p. 65.

[27] M.N. Lurie & B.G. Williams.: “Migration and Health in Southern Africa: 100 Years and still Circulating,” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access Journal, p. 36.

[28] J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan & E.Z. Chelkowska.: “A Century of Migrant Labour in the Gold Mines of South Africa,” The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, (1), p. 65.

[29] J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan & E.Z. Chelkowska.: “A Century of Migrant Labour in the Gold Mines of South Africa,” The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, (1), p. 66.

[30] J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan & E.Z. Chelkowska.: “A Century of Migrant Labour in the Gold Mines of South Africa,” The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, (1), p. 66.