Chinese civilisation stretches back to least 2000 BC. It became a single empire in 221 BC. [1] China was ruled by a series of dynasties until 1911 and from 1368 to 1644, the Ming Dynasty ruled over China. This was the last native Chinese dynasty. [2] The word ‘Ming’ means bright, and is a fitting name for the Dynasty that had many developments during its lifespan. [3]

Lineage[4]

The Ming Dynasty had a total of sixteen emperors. This article will focus on the changes that took place during rule of the following Emperors: Hongwu (first emperor), Yongle (third emperor), Yingzong (sixth emperor) and Chongzhen (sixteenth emperor).

Below is a full list of Ming Dynasty Emperors:

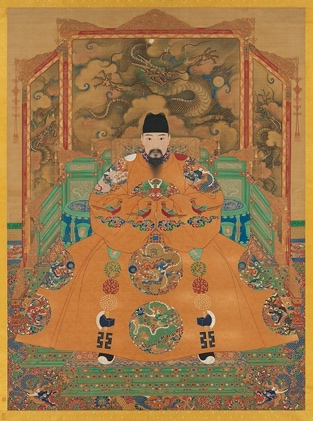

First Emperor: 1368 – 1398

Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (Taizu) Image Source

Second Emperor: 1399 – 1402

Jianwen Emperor, Zhu Yunwen (Huidi) Image Source

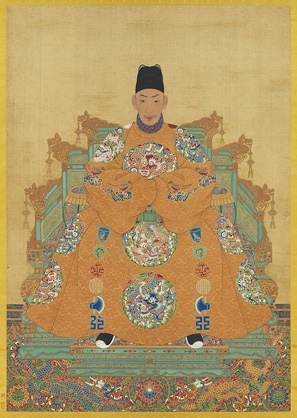

Third Emperor: 1403 – 1424

Yongle Emperor, Zhu Di (Chengzu) Image Source

Forth Emperor: 1425

Hongxi Emperor, Zhu Gaochi (Renzong) Image Source

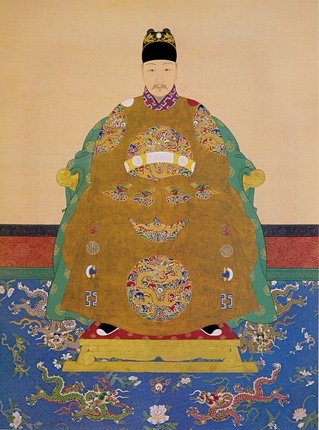

Fifth Emperor: 1426 – 1435

Xuande Emperor, Zhu Zhanji (Xuanzong) Image Source

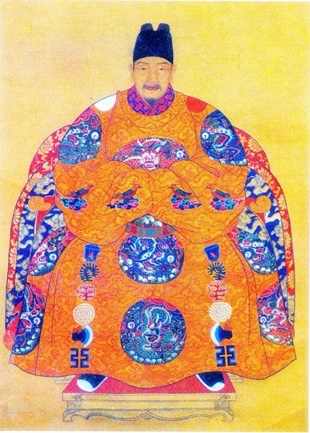

Sixth Emperor: 1436 - 1449 & 1457 - 1464

Zhengtong and Tianshun Emperor, Zhu Qizhen (Yingzong) Image Source

Seventh Emperor: 1450 – 1456

Jingtai Emperor, Zhu Qiyu (Jingdi) Image Source

Eighth Emperor: 1465 – 1487

Chenghua Emperor, Zhu Jianshen (Zianzong) Image Source

Nineth Emperor: 1488 - 1505

Hongzhi Emperor, Zhu Youcheng (Xiaozong) Image Source

Tenth Emperor: 1506 – 1521

Zhengde Emperor, Zhu Houshao (Wuzong) Image Source

Eleventh Emperor: 1522 – 1566

Jiajing Emperor, Zhu Haucong (Shizong) Image Source

Twelfth Emperor: 1567 – 1572

Longqing Emperor, Zhu Zaiji Image Source

Thirteenth Emperor: 1573 – 1620

Wanli Emperor, Zhu Yijun (Shenzong) Image Source

Fourteenth Emperor: 1620

Taichang Emperor, Zhu Changluo (Guangzong) Image Source

Fifteenth Emperor: 1621 – 1627

Tianqi Emperor, Zhu Youjiao (Xizong) Image Source

Sixteenth Emperor: 1628 - 1644

Chongzhen Emperor, Zhu Youjian (Sizong) Image Source

The rise of the Ming Dynasty

Up until 1368, Mongolian rulers held the Yuan Dynasty in China. [5] In Mongolian Law, various groups of indigenous Chinese people, especially the Han, were considered ‘lower class’. Chinese groups were considered ‘dregs’ in the social order. Many Chinese peasants were enslaved in large numbers, had their lands confiscated, and were excluded from governmental positions. [6] Non-mongolian foreigners, such as Marco Polo, the Persian Ahmad and the Uighur Sengge, were welcomed as patrons in Yuan China. It could be argued that this hospitality was not shown towards Chinese locals. Internal class tension was exacerbated in the 1340s by natural disasters and forced conscription of Han peasants for labour. [7] Various rebel groups began to assemble and prepare for a rebellion. Zhu Yuanzhang was one of the main leaders of these rebel groups. He did not come from an affluent background, and spent years begging for a Buddhist monastery [8]. At the time, Yuan militia burned down the monastery in an attempt to stop an impending rebellion. Yuanzhang worked his way up through rebel ranks in 1352 A.D., when he joined a group related to the White Lotus Society. In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang initiated a rebellion and captured Beijing. [9] This marked the official end of Mongolian control over China. Yuanzhang began the Ming Dynasty and took the title of Emperor Taizu, or the Hongwu Emperor. [10]

Government and Society

At the time, the Ming Dynasty had the most effective central bureaucracy in the world. Emperors were autocratic rulers who had absolute power over all aspects of life in their Empire. During the Ming Dynasty, the civil service system was perfected. Officials entered top levels of the bureaucracy by passing a government examination [11]. During Emperor Taizu’s reign, an office called the Censorate (Yushati) was made separate to the government. They investigated official cases of corruption and misconduct [12]. Each province had its own bureau that was attached to the central government. Instead of having a prime minister, the Emperor took personal control over the government and was assisted by a Grand Secretariat, also known as a Neige [13]. Castrated men, known as Eunuchs, were employed as advisors for the emperor. These advisors held a high position in the bureaucratic rank. By the 16th Century, weak Ming emperors were often dominated by their advisors. [14] The governmental structure of the Ming Dynasty lasted until China’s imperial system was abolished in 1911. [15]

During the beginning of his reign, Emperor Taizu enforced strict military discipline and reorganised the army to establish the ‘Brocade Guards’. These guards operated alongside spies and secret agents to purge corrupt officials. [16] Forms of punishment were severe and often included tattooing, severing of organs and castration, however, near the end of Taizu’s reign, these were outlawed in favour of corporal punishment and flogging. [17] In 1380 A.D., Taizu revised the legal code to ensure that his power could not be challenged in court. He also launched a series of land and tax reforms. [18] The palace guard launched an internal investigation 1380 A.D., this lasted for 14 years. A total of 30 000 executions were conducted during this time. [19]

The role of women

Women in Ming China had the ability to become property owners, if they were affluent enough. They also had access to literature when it was widely published. In the 17th Century, an anthology of Chinese poetry included poems from as many as 1000 women. Writer Li Yu is an example of an early feminist, arguing that women should be equal to men. [20]

In reality, women in Ming China lived domestic lives and bore children. Male children were more important than female children, and a common practice of killing female babies at birth was present. [21] This practice was officially discouraged but unofficially practiced. Status was strongly connected to class. Therefore, rural peasant women worked in the same conditions as men. Urban women, on the other hand, were employed in the fields of weaving and embroidery. [22] Upper class women were subjected to the practice of foot-binding, in an attempt to keep their feet small and feminine. When women’s feet were bound, their bones would often break and they could only make small strides when walking. [23]

Cultural Achievements

In 1406, Emperor Yongle transferred the capital of China from Nanjing to Beijing [24]. Yongle ordered the construction an imperial palace complex called the Forbidden City, which remains the world’s largest to date. In 1420, the Forbidden City was occupied by the court. [25] The capital became a cultural hub where different types of craftsmanship took place. Decorative techniques, including cloisonné, lacquerwork and furniture sculpting also reached a peak during this time. [26] Ornamental carvings from wood, porcelain, ivory and jade were some features during this time. Decorative ceramics that used different techniques were a trademark. [27] Porcelain was one of the Ming Dynasty’s bets exports. Porcelain is created by grinding china-stone and mixing it with china-clay. This mix is then baked until it becomes translucent. [28] In 1368, an imperial factory was created in Jingdezhen to produce ceramics for the imperial court. [29] A common ceramic technique of enamel painting combined with a blue underglaze, called ‘blue and white’ was imitated China’s neighbouring countries. This technique was later adopted by European countries, although most of the porcelain was still produced in the Jingdezhen factory. [30]

A blue-and-white porcelain dish with a dragon. Image Source

Beijing was the main bureaucratic and military centre, while towns like Nanjing became famous for their social life and festivals. [31] It is suggested that cultural achievements of the Ming Dynasty were characterized by a conservative and ‘inward-looking’ attitude. [32] Urban culture grew as Chinese cities expanded. Under the Ming regime, literary examinations were re-established. This, combined with the growth in urban culture, resulted in a higher literacy rate. Consequently, a literacy boom emerged during the Ming Dynasty. Books became affordable for commoners. Religious books, Confucian literature and civil service examinations guides were popular. [33]

Writers of vernacular literature made significant contributions to novels and drama. Many of the full-length novels were adaptations of ancient story cycles that stemmed from centuries of oral tradition. [34] Some classic novels include The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, and Journey to the West [35]. To accompany these books, woodblock illustration was implemented. This method allowed for publishers to easily reproduce images. It was also a trademark that distinguished publishers from each other. [36]

An image of Chinese woodblock print. Image Source

Traditional Chinese drama practice was banned during the Song dynasty, and led the practice underground and further south. During the Ming Dynasty, this was brought back. Tang Xianzu was a playwright that was popular during the Ming Dynasty. [37] The musical theatre forms of chuanqi and kunqu were implemented. These forms were adapted to form fuller-length operas. Furthermore, painting traditions of the Ming Dynasty can be categorized according to ‘literati painting’ of the Wu school and ‘professional academic’ painting of the Zhe school. [38] Individual artists became popular during this time, leaving traces of their own personal styles in their work.

Travel, trade and scientific achievements

China sent their trade goods to western Asia and Europe via the Silk Road. This was a 6 400 kilometre overland journey that ended at the Mediterranean sea. [39] Another way that they traded was via ships on the ocean. Chinese junks were unique ships that were used from as early as the 5th Century AD.[40] China’s first imperial treasure fleets were commissioned by the Mongols who held the Yuan Dynasty, between 1271 and 1368. [41] The Chinese hoped to discover new lands and to establish new trading partners. They often returned with exotic animals, spices, ivory and prisoners of war. [42]

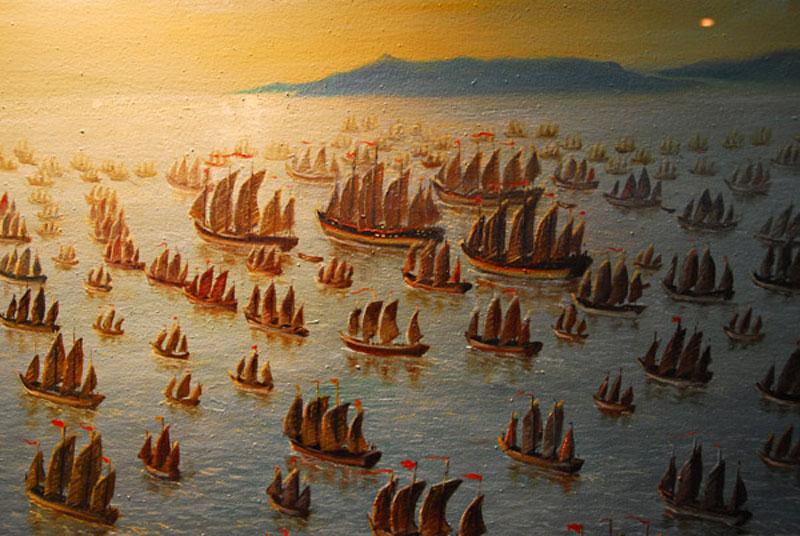

This fleet was extended by Emperor Yongle during the Ming Dynasty. Emperor Yongle invested a large amount of money into extending the fleet. Chinese junks had two predominant features: a yuloh oar for steering and stiffened sails supported by bamboo battens. [43] The yuloh rudder allowed ships to steer and turn, without having to take the rudder out of the water. Legend suggests that this design was inspired by the way that fish use their tails to thrust themselves forward [44]. Junks were huge, with a length of 122m and width of 46m.

An oil painting of Zheng He’s fleet. Image Source

The Chinese fleet reached its peak in the 15th Century, under the leadership of Muslim eunuch, Admiral Zheng He. [45] He conducted seven maritime expeditions. Emperor Yongle instructed Admiral Zheng He to explore the oceans in search of goods. [46] Between 1405 and 1433, representatives were sent to other countries to ask for tribute in money or goods to show that they recognised the power of the Chinese Empire. Zheng He’s fleet reached a total of 37 countries, expanding China’s influence along Asian sea routes. [47] China’s trade potential and peaceful voyages left a mark on the countries that they visited, demonstrating China’s trade potential and naval strength. [48] Although Zheng He is often depicted as an ‘ambassador of friendship’ who initiated contact between China and other countries, revisionist historians suggest that his voyages were attempts to colonise China’s neighbours.[49] The intention behind Emperor Yongle’s instruction was to establish tributary or vassal states in the East, and expand China’s hegemonic rule. [50] If China had a pax Ming (a period of peace in East Asia), the world would have seen the Chinese emperor as a legitimate ruler of the East. [51] Zheng He’s fleets were accompanied by military personnel that established depots in Southeast Asia, thus allowing them to control the waterways. [52] Chinese technology was far more advanced than anything in Europe at the time. The voyages of the Ming Dynasty demonstrated China’s technological and navigational ability to the world in the 15th Century. [53] Because of this, it was believed that China would discover the ‘new world’ before Christopher Columbus. [54]

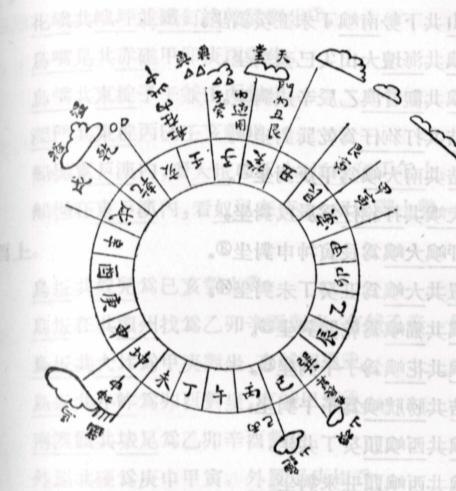

Foreign countries were impressed by Chinese inventions and tradeable goods. Chinese inventions included the magnetic compass, paper, the wheelbarrow, suspension bridges, gunpowder, porcelain, movable type and the mechanical clock. The most commonly traded items from Zheng He’s fleet were silks and spices. [55] Zheng He’s fleet used a star chart and magnetic compasses to navigate the oceans. This technology allowed for more accurate travel towards their destinations. Zheng He departed for his final voyage in 1431 and visited Indochina, Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), India, Iran, Zanzibar, the Red Sea and Java. [56] This voyage would mark the last of the Chinese fleet, and when it returned in 1433, China ended its expansionist policies.

A diagram of Ming Dynasty mariner’s compass. Image Source

Looking inwards after 1433

During the first five decades of the Ming Dynasty, The Mongols were driven north to what is now known as Mongolia. [57] Following this, the northern border a place of increasing threat. After Emperor Yongle’s death in 1424, the Ming Dynasty became extremely vulnerable to outside invasion. [58] In 1449, Mongol-speaking Oirat peoples invaded China. The emperor at the time, Yingzong, led an unsuccessful counterattack. Emperor Yingzong was ambushed at Tumu. [59] As a result, he was taken hostage. This incident caused a shift from expansionist policy to a defensive frontier strategy. Yingzong’s China lacked the military resources to defend against the Mongols. In 1474, a barrier over the Qin Dynasty walls were built out of brick and stone. This barrier became known as the Great Wall of China. [60].The Great Wall was strengthened and maintained throughout the Ming Dynasty.

There were also struggles with groups from other nationalities. To the south of China, early Ming Emperors attempted to invade Northern Vietnam, but were unsuccessful.[61] The boundary lines between China and Vietnam remained the same, and Ming Emperors stopped their attempts to push further south. The nomadic Jurchen people of the northeast placed pressure on the Ming armies until they gained the territory right until the Great Wall. [62] The Jurchen people stemmed from the Jin dynasty and consisted of both Mongols and Chinese. Jurchen leader, Huang Taiji, changed the name of the Jurchen people to the Manchus and introduced Chinese practices to his people. [63] Across the ocean, Japanese and Chinese pirates initiated costal raids, however, these did not threaten the control of the Ming Dynasty [64]

The Great Wall of China Image Source

Trade with the West & Decline of Ming Dynasty

By 1514, Portuguese merchants had reached China. Within the next 35 years, a trading station was established at Macao. [65] Chinese porcelain became very popular in 1604. At the time, Portuguese ships carrying Chinese porcelain were captured by the Dutch. [66] The porcelain was later put up for auction in Europe, starting a craze. By 1557, China’s tribute trade system shifted towards maritime trade. [67] This meant that China focused on producing goods for export and allowed a European presence in their empire. In following years, China’s mercantile relationship with the west would strengthen.

During the late 16th Century, the bureaucratic structures of the Ming Dynasty began to weaken. Some internal factors that contributed to the decline include conflict within government, interference by palace eunuchs, factional fighting between civil officials and weakening imperialism. [68] It is suggested that many of the emperors after Yingzong were dominated by their advisors, causing an oversight of many important issues. [33] In April 1644, rebel leader Li Zicheng took control of Beijing. This caused the Chongzhen Emperor to commit suicide, thereby becoming the last Ming emperor. [69] Following this, a change in leadership happened again when Li Zicheng initiated negotiations with Wu Sangui, a powerful northern commander, for the Manchus to pass through the great wall. [70] This was a fatal mistake, as the Manchus usurped control and invaded Beijing. The Ming Dynasty was succeeded by the Qing Dynasty, with Huang Taiji becoming the new emperor. The Qing Dynasty lasted until the abolition of imperial rule in 1911. [71]

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by

Ilse Brookes, Amber Fox-Martin & Simone van der Colff

[1] J. Bottaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, Oxford in Search of History: Grade 10 Learner’s Book.

[2] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[3] B. B. Peterson: “The Ming Voyages of Chen Ho (Zheng He), The Great Circle, (16), (1), 1994, p. 43.

[4] S. H. Tsai: The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty , p. xii.

[5] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[6] C.O. Hucker: The Ming Dynasty Its Origins and Evolving Institutions, p. 4.

[7] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[8] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[9] Ibid.

[10] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[11] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 167.

[15] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[16] L. Yang, Y. Wang, S. Yang: “A Probe into the Anti-Corruption Mechanism behind Ming Dynasty’s Appointment of Touring Censorial Inspectors and the Causes for Its Failure,” Scientific Research Open Access Chinese Studies, (3), (5), 2016, p. 38.

[17] S.H. Tsai: The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty, p. 17.

[18] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[19] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[20] J. Bottaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, Oxford in Search of History: Grade 10 Learner’s Book.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[25] Author Unknown: “Forbidden City,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Forbidden-City (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[26] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[27] Ibid.

[28] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[29] Ibid.

[30] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[31] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[32] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[33] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[34] Ibid.

[35] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[36] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[37] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[38] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[39] J. Bottaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, Oxford in Search of History: Grade 10 Learner’s Book.

[40] B. Lavery: Ship: 5000 years of maritime adventure, p. 61.

[41] Ibid.

[42] J. Bottaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, Oxford in Search of History: Grade 10 Learner’s Book, Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[43] B. Lavery: Ship: 5000 years of maritime adventure, p. 61.

[44] Ibid.

[45] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 167.

[46] B. Lavery: Ship: 5000 years of maritime adventure, p. 61.

[47] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 167.

[48] B. Lavery: Ship: 5000 years of maritime adventure, p. 61.

[49] G. Wade: “The Zheng He Voyages: A Reassessment,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, (78), (1), 2005, p. 44.

[50] B. B. Peterson: “The Ming Voyages of Chen Ho (Zheng He), The Great Circle, (16), (1), 1994, p. 43.

[51] G. Wade: “The Zheng He Voyages: A Reassessment,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, (78), (1), 2005, p. 44.

[52] Ibid. p. 47.

[53] B. B. Peterson: “The Ming Voyages of Chen Ho (Zheng He), The Great Circle, (16), (1), 1994, p. 43.

[54] Ibid.

[55] B. Lavery: Ship: 5000 years of maritime adventure, p. 61.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[58] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 166.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid. p. 167.

[61] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[62] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 240.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)

[65] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 167.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Author Unknown: “Ming Dynasty,” History.com [online], available at https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/ming-dynasty (Accessed: 20 June 2020)

[68] A. Hart-Davis (ed): History: The Definitive Visual Guide from the dawn of civilisation to the present day, p. 167.

[69] Ibid. p. 240.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Author Unknown, “Ming Dynasty,” Brittanica.com [online], available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ming-dynasty-Chinese-history (Accessed 30 March 2020)