In 1912 Enoch Mgjimia, a lay preacher and independent evangelist, broke away from the Wesleyan Methodist Church and joined the Church of God and Saints of Christ, a small church based in the United States of America. In November 1912 he began baptising his followers in the Black Kei River near his home in Ntabelanga. He decided to call his followers “Israelites” as he identified with the Hebrews of the Old Testament. Towards the end of 1912 Mgjima predicted that the world would end on Christmas after 30 days of rain. As a result of his predictions his followers stopped working and ploughing their fields. Needless to say, the end did not come. Over the years Mgijima’s visions became more and more violent. He was asked to renounce his visions by the leaders of the Church as they could not condone the preaching of conflict and war, but Mgijima refused, and was excommunicated. As a result, in 1914 the South African Church of God and Saints of Christ split, with one of the groups following Enoch Mgijima as Israelites.

Mgijima owned a piece of land in Bulhoek and as his following grew, he erected a building to be used for religious ceremonies on one of the pieces of land. The building was rarely used as it could not accommodate the congregation and was soon replaced by a larger, temporary marquee. The space soon became insufficient and Mgijima made alternative plans for his Passover celebrations. He came to an agreement with the local Shiloh Mission Station, which allowed him to host the event on their premises in 1917.

The following year Mgijima was refused the same opportunity because one of his followers had broken one of the mission station’s rules, which decreed that only evangelists could lead church meetings. In an attempt to find another location Mgijima’s lawyer contacted the government’s inspector of African locations at Kamastone, Mr GE Nightingale, for permission to hold Passover on the commonage at the Kamastone sub-section. Permission was granted on the condition that the churchgoers leave immediately after the celebration. In 1919 the same request reached the Superintendent, but due to the objections of other lot owners it was rejected. Mgijima then asked to hold the festival at Ntabelanga, in the Bulhoek sub-section, and was given the go-ahead.

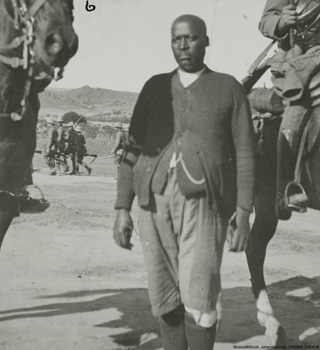

Enoch Mgijima shortly after his arrest. Source: http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/ © Museum Africa

Enoch Mgijima shortly after his arrest. Source: http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/ © Museum Africa

At one of his services early in 1919, Mgijima expressed a prophecy that marked a turning point: he stood in front of his tabernacle and uttered the words “Juda, Efrayime, Josef, nezalwane” (Judah, Ephraim, Joseph and bretheren) which, according to his followers, could be heard by Isrealites all over South Africa. The call led to a pilgrimage, with followers from all over South Africa – about 3 000 people – arriving at Ntabelanga to await the coming of the Lord. The pilgrims proceeded to squat on the property, erecting a tabernacle and some huts – without registering with the authorities or paying tax.

In 1920 Superintendent Nightingale came across the squatters while inspecting the location. He contacted Mgijima, who said that the assembled people had not been able to attend the Passover festivities of the previous year and were there to attend a special service. According to Edgar (2010), the events transpired as follows: Mgijima applied to Nightingale early in 1920 for permission to let his followers attend the Passover festival at Ntabelanga, explaining that many were travelling from afar. Nightingale was reluctant to grant permission as he had heard rumours that some Africans were settling on the land permanently. Mgijima assured the authorities that the people squatting on the land would leave as soon as the Passover was concluded, and the arrangement was accepted.

Mgijima was in a difficult position – he had called all his followers to Bulhoek to await the end of the world, but they were squatting on British land. He had not explained the real reason for the influx of people to Nightingale, and was now in a precarious position – there was the possibility that his credibility would be lost. He could not send his people away, even though he had told the authorities he would. Claiming that there was a lack of firewood and food, he decided to extend the Passover period to the end of May, 1920. When word of this extension reached Nightingale, he paid Mgijima a visit on 8 June 1920, and found many more houses being erected. Again the prophet made excuses for breaking the arrangement. Mgijima explained their presence by saying that many people had fallen ill and some did not have money to travel home. He said Passover would take place on 18 June and the illegal squatters would leave Bulhoek after the event.

In July the headman of Kamastone complained to Nightingale that more Israelites were arriving and more houses were being built. This time Mgijima avoided contact with Nightingale. The Inspector had lost all trust in Mgijima and he began trying other ways of removing the squatters from Ntabelanga.

Conflict

The Israelites were in an awkward position as Mgijima had convinced them to get rid of all their worldly possessions in preparation of his envisioned Armageddon. They became desperate and started to steal livestock from farmers and other residents in the area. At this point the Department of Justice decided that law and order had to be restored at Bulhoek. A register of all the squatters was planned to help remove them from the property. To justify the removal, the state used provisions under the Native Locations Act of 1884 for squatting on Crown land, and other provisions under Government Notice for building on the commonage without permission. On 7 and 8 December 1920 the Senior Magistrate of Queenstown, ECA Welsh, visited Ntabelanga accompanied by 100 police officers under the command of Major Hutchons from Grahamstown. The police force set up their tents 500 metres from the Israelites.

All discussions and negotiations with the Israelites failed and they refused to submit their names for a register or acknowledge the government’s authority. They argued that God was greater than man, and they would listen only to God as they were occupying His land. The Israelites were defiant and aggressive and confronted the group of police officers. They could not be forced to register and the police officers retreated to set up camp for the night. The Magistrate and Major both returned to Queenstown, leaving Captain Whittaker in charge of the police force while they waited for further instructions from Pretoria. As part of the church service 1000 Israelites began marching as the negotiations came to an end. Thinking that the Israelites were preparing an attack, the officers fled to a farm five kilometres away – the Israelites did not seize their supplies and belongings.

When local farmers and other residents heard about the incident they were alarmed. Captain Whitaker sent for reinforcements from Queenstown and a group of volunteers arrived with Major Hutchons. Their strategy called for a defensive position until more men arrived from Pretoria. The situation was extremely tense as the Israelites were gripped by religious fervour and engaged in heated exchanges with government officials. Major Hutchons spoke to farmers, head-men and chiefs in the area, guaranteeing their safety in the hope of preventing them from taking the law into their own hands.

Pretoria refused to send reinforcements and while the volunteers returned to Queenstown, the police stayed to patrol the area. The situation worsened on 14 December 1920 after an incident in which two Israelites were shot by farmer John Mattushek and his servant, a Mr Klopper. The incident took place after Mattushek saw three Israelites searching for cattle-feed in the area. Mattushek became convinced they wanted to kill him. They clashed and Mattushek killed one of the men and wounded another. Farmers in the area feared revenge attacks and moved their families to Queenstown while Mattushek and Klopper were arrested and charged with assault and culpable homicide. When the case came before the court in April 1921 the principal Israelite witness did not appear as the Israelites feared that the government would arrest them if they left Ntabelanga.

Government intervention

Despite the explosive situation, the Native Affairs Department felt that the conflict could be solved in a peaceful manner. A call was made for national government intervention. A group of “moderate” Africans from the Eastern Cape – consisting of JT Jabavu, Meshach Pelem, Patrick Xabanis and Chief Veldtman – were asked by the government to try to persuade the Israelites to leave. When the delegation failed, a group of high-ranking government officials met with Israelite leaders in Queenstown. On 17 December 1920 the group met but nothing was achieved.

Prime Minister Jan Smuts decided to send the newly appointed Native Affairs Commission to Queenstown to negotiate with the Israelites. Enoch Mgijima sent his brother, nephew and another high-ranking church member to negotiate on his behalf. The commission met with the Israelites met on 6 and 8 April 1921, and said it would consider making Ntabelanga an Israelite centre of worship. The Israelites rejected the commission’s porposals and claimed that they “wished to obey the law of the land, but Jehovah was more powerful than the law” and they would not “offend him by disregarding his wishes and obeying the laws of men”.

Another meeting between the Israelites and the commission took place on 11 May 1921, but again nothing was achieved. The Isralites were simply not prepared to leave, and their continuing presence saw support for the commission drop among non-Israelites in the area.

The members of the commission asked the Department of Justice to send a police detachment to remove the illegal squatters. This, they hoped, would be enough to intimidate the Israelites and prevent bloodshed.

The Israelites were being condemned for their actions from several quarters. On 17 May 1921 the newspapers Imvo Zabantsundu and The Star, as well as the General Council of the Transkeian Territories, urged the government to enforce the law at Bulhoek. The Council of the Transkeian Territories passed a resolution criticising the Israelites. The South African Native National Congress, later the African National Congress, encouraged the Israelites to return to their homes to avoid bloodshed.

The South African government began preparing to use force. The Department of Justice ordered the South African Police (SAP) and the Union Defense Force (UDF) to gather a large force to take action. A total of 993 policemen and 35 officers from various provinces were mobilised and gathered in Queenstown under the command of Colonel TC Truter from Pretoria, with support from the UDF and the South African Medical Services. The UDF suggested a fly-by with two aircraft as an intimidation tactic. Although bombs would be dropped they would fall wide to prevent injuries. This plan was eventually abandoned as authorities felt it would only strengthen the Israelites’ resolve and would endanger lives.

The Israelites were well aware of the force being assembled against them and prepared themselves for the confrontation. The men marched and trained every afternoon, after which they slaughtered an ox and dipped their assegai tips in its blood. During the night they left their village and took up strategic positions in the surrounding mountains and hills.

By 20 May 1921 the SAP and UDF force was ready and the next day Enoch Mgijima was given an ultimatum. Colonel Truter announced that, as a representative of the government, he was duty-bound to arrest those men who had warrants against them; he had to ensure that all illegal squatters left the area; and he had to destroy all the illegal houses. The next day Mgijima sent Silwana Nkopo and Samuel Matshoba to deliver a letter to Colonel Truter, in which he defended the Israelite position and reiterated his refusal to move.

Tragedy

On 23 May 1921 the police mobilised and moved to a farm close to Bulhoek. The force was armed with machine guns, a canon and artillery. Some men remained in Queenstown as there were rumours of a possible Israelite attack on the town. During the night the final preparations were made for the operation and the next morning the government force took up their positions on the hills at Bulhoek.

The Israelites were also readying themselves, and about 500 men wre armed with clubs, assegais and swords. Colonel Truter made a final attempt to prevent violence by sending two Xhosa-speaking officers to negotiate. However, they were told: “From Jehovah, we will not allow you to scatter our people from Ntabelanga. We will not allow you to burn our huts, and we will not allow you to arrest the two men you wish to.”

It is not clear how the battle started but some reports say it may have begun after a shot was fire by accident. Soon afterwards the Israelites launched an attack and Colonel Truter ordered his force to advance. Warning shots were fired over the heads of the approaching Israelites but they were not deterred. The troops were ordered to shoot and a large number of Israelites were wounded. Some of the injured got up and continued to charge. One of the commanding officers, Colonel Woon, said the Israelites were “the most determined and fanatical I had ever experienced, and it was only by shooting them down that the attack could have stopped”. About 200 people were killed, more than 100 were wounded and 141 were arrested, including Enoch Mgijima and his sons.

In November 1921 the trial of the 141 Israelites arrested began in Queenstown. They were charged with “violent and forcible conduct against the authority of the state” (Edgar, 2010: 37). The trial lasted two weeks, at the end of which all 141 were found guilty. The judge, Thomas Graham, sentenced Mgijima, his elder brother Charles, and Gilbert Matshoba to six years’ hard labour at DeBeer’s Convict Station in Kimberley. A few were given suspended sentences, but the remaining 129 Israelites were sentenced to between 12 and 18 months of hard labour. Mgijima was released from prison in 1924 and died some years later, on 5 March 1929.

Some historians believe that the Israelites were the victims of the segregationist government, as their struggle was a fight for land and exemption from taxes, as well as self-rule to end White oppression. Others argue that they were endangering the people around them as well as taking possession of land they did not own. It is difficult to say what whether the SAP could have acted differently. The government faced ongoing criticism for years after the incident.

NOTE: Sources vary on the number of Isrealites that gathered at Ntabelanga as well as on the exact number of victims of the massacre. Therefore all of the numbers in this piece are approximate and based on numerous sources (below).