March 20, 1602 marked the beginning of the inexorable end for many a state in the then known world. On that day, four hundred years ago, a group of Dutch merchants and independent trading companies, impatient with the monopoly that the Portuguese had established over the spice trade with East Asia at the end of the fifteenth century and keeping the British imperial merchants in check, founded the Vereenigde Landsche Ge-Oktroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie, better known to the Anglophone world as the Dutch East India Company or simply the VOC. The executive directorate of the VOC was called the Heeren Sewentien or the "Lords Seventeen". The Company had a federal character, comprising six chambers.

The VOC was granted a government charter, which effectively guaranteed it the right to the spice trade monopoly in East Asia. However, this government charter secured the VOC more than a trade monopoly: it gave the VOC the power to colonise whichever territory it desired and enslaving the indigenous people according to market requirements and VOC political imperatives. This meant that the VOC did not merely get involved in trade wars with European and Asian powers from its headquarters in Batavia, but waged full-scale warfare on indigenous people in those countries that would not cooperate with its demands for tea and spices such as cloves, nutmeg and pepper, or who resisted the cash-crop economy that the VOC was forcing onto them. A prime example is the island of Banda in the Indonesian Archipelago. The VOC simply killed off the Bandanese, appropriated the island, and cultivated nutmeg as a monoculture, using slave labour from neighbouring countries.

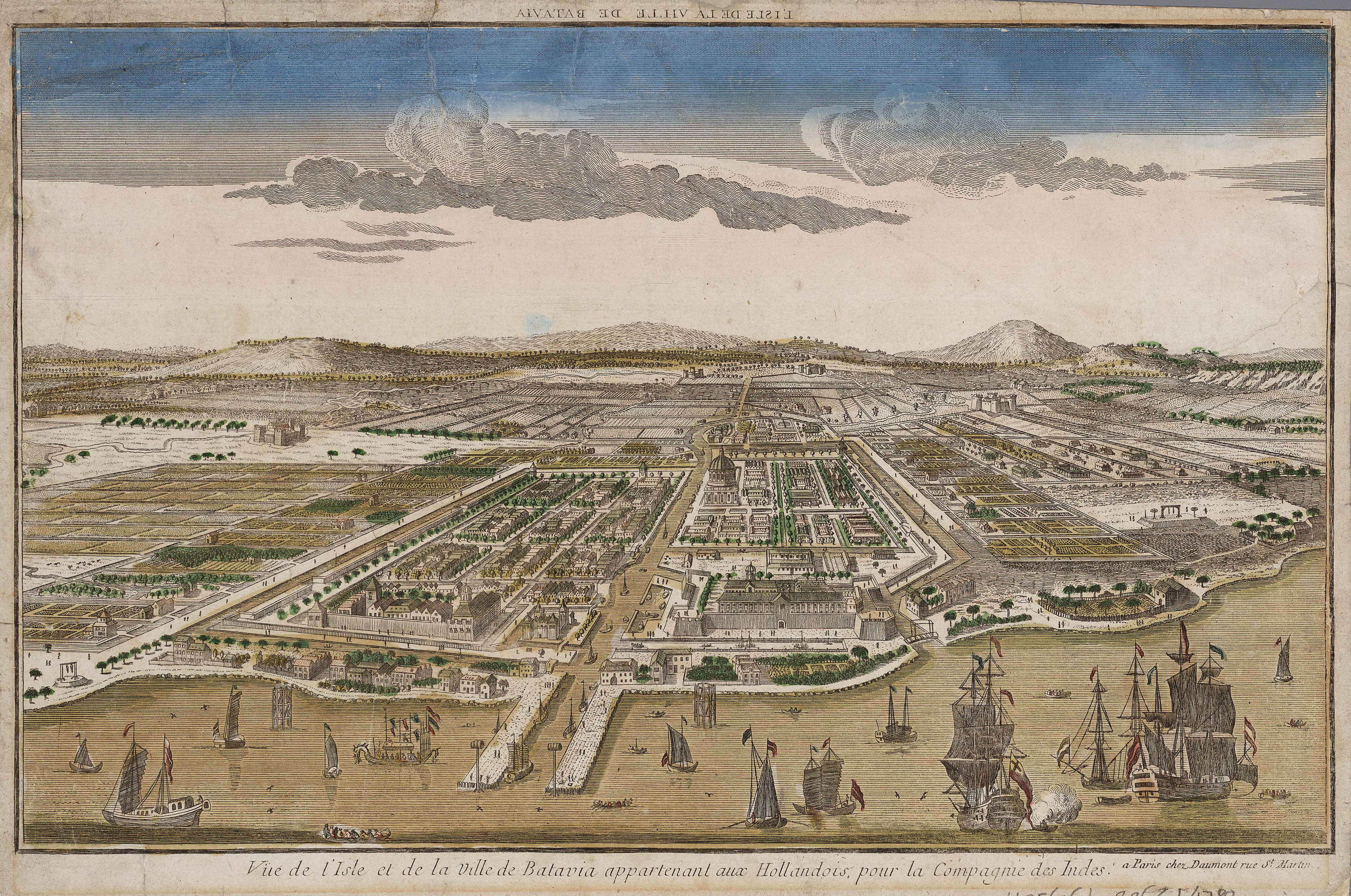

The VOC monopoly of the spice trade meant that it determined the prices of the commodities, their production and availability and determined which other powers could participate in the trade, setting out clearly the conditions under which this would be possible. In addition the VOC developed the world's first stock market in Amsterdam with durable assets and controlled investment schemes. It should be noted that the spice trade route was also used to transport precious metals such as gold and silver for European destinations. As a result a number of trading stations were built across East Asia. In terms of trade and commerce Holland reached the height of its power in this period, and sympathetic historians look back at this period as its golden age.

However the extent of suffering wreaked by the VOC in this period is incalculable. Many an East Asian country, such as Indonesia, that had been colonised by the Dutch because of the VOC project, still have to deal with the legacy of colonisation and slavery four hundred years later.

Present-day South Africa is no different in this regard. In 1649 a recommendation, called a Remonstrantie, was made to the Directors of the VOC to establish a refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope for ships passing it en route to the lands of tea and spices. In this memorandum the quality of the land at the foot of Table mountain and the shores of Table Bay were praised for their fertility. Visions of fresh fruit and vegetables were conjured up. The "friendliness" of the indigenous pastoralists, who would supply fresh meat was likewise extolled. Hence in 1652 the VOC sent a group of Dutchmen under the command of one Jan van Riebeeck to set up a refreshment station and to provide facilities for crew who had fallen ill to diseases such as scurvy on the long journeys between Holland and East Asia.

Within weeks of his arrival at the Cape, Van Riebeeck requested slaves to work at setting up the refreshment, as the Cape was not to be a colony, with the right to enslaving the indigenous population. Good relations with the indigenous people, the Khoikhoi and the San, were to be maintained. Although Van Riebeeck did not receive slaves immediately, and although the Cape was not to be more than a refreshment station, the economic demands and the greed for land soon reversed Van Riebeeck's mandate and instructions. Within four years of Van Riebeeck's arrival, the first war between the Khoikhoi and the Dutch broke out, as the Khoi clans tried to drive away the Dutch who had appropriated their land, forcing them into less fertile areas of the region. Soon the colonial project was well underway. With the systematic importation of slaves from mainly Dutch East Asia the Cape economy developed into a slave-based economy. This had profound repercussions at all levels of society, determining as it did social relations based on a slave/servant-master paradigm that translated within a short period of time into a racial hierarchical social order. Europeans/whites became the masters, while the indigenous population was either decimated or subjugated to the level of a slave/servant class.

Holland's power started declining towards the end of the eighteenth century, giving way to the burgeoning British imperialist power. This coincided, too, with Europe's discovery of its greater love for the fashionable beverage called coffee in comparison to the more mundane tea. This meant that Europe's commercial interests were being directed towards the Caribbean instead of Batavia.

The hegemony of the VOC is being celebrated and commemorated variously in The Netherlands as the golden age of Dutch commerce. Then again many are the critical voices, both in The Netherlands and in countries which fell prey to the activities of the VOC, that point to the oppression and destruction that resulted from the VOC project.

Four hundred years later, South Africa, like Indonesia, is still inextricably bound up with the European economy and is still struggling to come to terms with the violent legacy of the VOC.