On October 25 1991, ninety-two organisations that were united in their opposition to apartheid gathered in Durban to form the Patriotic Front. The Front deliberated over the negotiation process. During the two days of discussion the mechanism and technicalities of transition and a changeover of political leadership were clarified. At the end of the conference, all organisations agreed that an interim government was required to manage the transition. Because the National Party government had a vested interest, it was not deemed suitable to manage and monitor the transfer of power. Clear guidelines were put forward on the responsibilities of the interim government. That is, to take non-partisan control of the security forces, the electoral process, state media, and define areas of budget and finance, to allow international participation of South Africa in global affairs and to elect a constituent assembly based on a one-person-one-vote basis in a united South Africa, which would draft and adopt a democratic constitution.

Introduction ↵

At first glance, one may be unsure of when exactly negotiations to end apartheid began. Hassen Ebrahim (1998) states that “there is little consensus about when negotiations began and who imitated them”. As possible starting points, he mentions De Klerk’s 1990 speech in Parliament, the first plenary of CODESA in December 1991, and in 1985 when Nelson Mandela initiated discussions with P.W. Botha’s government. Ebrahim notes that it is generally accepted that the latter view is the most accurate. [i]

CODESA involved two plenary sittings, and a period of Working Group activity in between. Therefore, this article uses an artificial division between Codesa 1 and Codesa 2. Codesa 1 was the first sitting of a formal multiparty negotiation forum to negotiate the principles of a new constitution and the composition of an interim or transitional power to manage the transitional period. It dealt with substantive matters rather than merely eliminating obstacles to negotiation. It is a significant event as it democratically produced the Declaration of Intent, which committed all parties to “united, democratic, non-racial, and non-sexist state”, thereby signalling a break from the Apartheid past. [ii] Codesa 1 set up an elaborate negotiation and management structure, including 5 Working Groups to negotiate substantive issues after the plenary. Two important issues for the convention were constitutional principles for a new constitution and an interim power, as well as the lead up to a constituent assembly which would write up the final constitution. The convention also witnessed the illuminating and fiery exchange between President De Klerk and Mandela, which highlighted an unresolved issue between the African National Congress (ANC) and the National Party (NP), the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto weSizwe (MK).

Codesa 1 generated hope but also took place in a period marked by uncertainty, mass action and increasing violence, violence involving the government and the security forces, the African National Congress (ANC), and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). It is important for one to look not only at the participants of Codesa (1) but also at the significance of those parties or organisations which did not attend and those who were completely against the convention or negotiation. Such parties include: The Conservative Party (CP), the Herstigte Nasionale Party (HNP), the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), and the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO). The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) was also absent for the plenary, after withdrawing in the preparatory phase, like Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the IFP who withdrew because of the exclusion of the Zulu king. However, the IFP delegation remained. Another important feature of Codesa 1 and its build up was the larger role played by the ANC and the NP government in influencing negotiations and decision making, and the unhappiness this produced in some of the smaller parties. Furthermore, tensions were also evident in the period between the ANC and the IFP.

Important Events Prior to CODESA

Harare Declaration ↵

On 21 August 1989 the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) published the ‘Harare Declaration’ [iii] , which according to Hassen Ebrahim, “contained the first real vision of a transition to democracy”. [iv] The Harare Declaration was drafted soon after Namibia was granted independence from South Africa through negotiation. The declaration symbolized a recognition by African leaders that negotiation was a possible option for bringing about change. It subsequently “determined to a large extent the ANC’s approach to the transition”. Furthermore, then ANC president Oliver Tambo invested a great deal of energy in lobbying African governments to support the declaration. [v]

The subject of the declaration was the “question of South Africa”. The OAU believed that the circumstances on the ground were such that, if the South African government played its part, negotiations could take place to end apartheid. The declaration called for South Africans to get together to negotiate and to agree on measures to transform the country into a non-racial democracy. The outcomes of such negotiations were to be a new constitutional order based on a set of principles. In its ‘statement of principles’ the declaration outlines nine such principles for South Africa and all its people, including: a united, democratic and non-racial state; equal citizenship; the right to participate in government on the basis of a universal suffrage, exercised though one person one vote, under a common voters’ roll; universally recognized human rights, freedoms and civil liberties, protected by a Bill of Rights; a new legal system guaranteeing equality before the law; an independent and non-racial judiciary; an economic order which promotes the well-being of all South African; and a South Africa that respects the rights, sovereignty and territorial integrity of all South Africans. [vi]

The declaration outlined the steps to be taken by the South African government for a necessary climate for negotiations to be created, where free political discussion could take place. It also consisted of guidelines for the process of negotiation. Negotiations were to establish the basis for the adoption of a new constitution by agreeing on the mentioned principles. After agreeing on these principles, the parties were to negotiate the mechanism for drawing up the new constitution. The negotiating parties would have to agree on the role of the international community in ensuring a successful transition to a democratic order. They would need to agree on the formation of an interim government to supervise the process of the drawing up and adoption of a new constitution; govern and administer the country, and effect the transition to a democratic state, including the holding of elections. The declaration then ended with a ‘programme of action’ for the OAU regarding the above. [vii]

The End of the Cold War and Disintegration of the Soviet Union ↵

The end of the Cold War and the disintegration and eventual fall of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991 (as well as prior to 1989) was of significance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activities and negotiations. During the Cold war, the superpowers sought spheres of influence globally and on the African continent. The apartheid government made use of this geopolitical context to defend apartheid and quell resistance. It did so by labelling parties involved in resistance as ‘communists’. South Africa was being protected from communism and this narrative would sit well with the United States and Britain. At the same time, the ANC and the SACP were given support, financially and in training by the USSR, as well as by Cuba, thereby making the Apartheid government’s narrative seem plausible to outsiders. However, after the end of the Cold war, and the disintegration and eventual fall of the Soviet Union, the Apartheid government could not play the ‘anti-communist card’ any longer. On the other hand, funding and support from the USSR and Cuba (as a proxy of the USSR for funding) for the ANC (and SACP) would no longer be forthcoming, as there was no more Cold War to motivate this and because Russia was going through its own economic transformations. Therefore, the end of the Cold War and fall of the Soviet Union provided an impetus for the National Party (NP) government and the ANC to enter negotiations. The NP could no longer rely on the ‘anti-communist’ rhetoric and the ANC did not have enough support and funding for Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) and a military campaign. [viii]

Peace Accord ↵

In August 1991, the Consultative Business Movement (CBM), an organization representing a section of church and business leaders, led the “National Peace Initiative” to deal with the issue of violence. It resulted in the first multi-party agreement, the ‘National Peace Accord’ being signed in September 1991 [ix] . As stated in the Sunday Times on 2 September 1991, ‘29 political, state and trade union organizations bound themselves to a code of democratic values and pledged themselves to search together for peace.’ [x] The signing ceremony was held on September 14, 1991 at the Carlton Hotel in Johannesburg and the accord was signed by the ANC, the National Party and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). It furthermore set up the machinery to “monitor, mediate and investigate violence”. [xi] This agreement created the chance for bilateral meetings between the ANC and the NP to consider convening the all-party congress. [xii]

Early announcements of talks

Mandela’s Breakthrough – January 1991 ↵

According to Allister Sparks, as the newly unbanned liberation movements were adapting to political activity in a changed environment and had ended “a series of preliminary agreements with the government”; De Klerk refined his strategy for a power-sharing constitution instead of majority rule. The then constitutional affairs minister, Gerrit Viljoen, outlined the government’s constitutional thinking at a round of four provincial congresses of the NP in 1990. [xiii] Sparks outlines these proposals:

“There should be a bicameral Parliament, consisting of a House of Representatives of three hundred members elected by universal franchise, and a Senate of one hundred and thirty members – ten from each of ten federal regions or states, plus ten from each of three “background groups” in the population, English, Afrikaners, and Asians (in a major racial concession, the Afrikaans-speaking coloured people were now to be regarded as Afrikaners).” [xiv]

As Allister Spark points out, this would have meant in practice that the ten Black 'tribal' groups, the English, the Afrikaners, and the Asians, would each be represented by ten senators in a racially structured upper house. Bills would have to be passed in both houses, but would require a two-thirds majority in the Senate. This would have meant that the white population and their allies in the old apartheid parties would be able to stop any attempt at altering South Africa’s socio-economic structure. [xv]

There would be twenty-six cabinet ministers in the executive, half from the regions and ‘background groups’ and half appointed by the president. The president would be a rotating chairmanship of a ‘collegiate cabinet’ that would need to reach decisions by consensus. Therefore, the executive would also be able to block attempts at socio-economic restructuring. Furthermore, Gerrit Viljoen also proposed a six-member advisory council, selected half from the ten regions and three ‘background groups’ in the Senate and half from the popularly elected House of Representatives. The council would then decide by a two-thirds majority, which of conflicting versions of a bill coming from the two Houses of parliament should become law. This would result in a veto over the popular will in the House of Representatives. [xvi]

Allister Sparks (1994) argues that this was “a formula for giving the illusion of popular democracy but denying the substance”. South Africa would have a system of one person one vote, but the parliamentary chamber elected by this system would not be able to change anything. [xvii] The government was not negotiating for black, majority rule but spoke of power sharing. The question then was around who would negotiate the new constitution. President De Klerk wanted it to be done by a convention of all existing political organizations, as opposed to an elected constituent assembly. De Klerk believed that the NP and its allies would be reduced to minority status in a popular vote for a constituent assembly while the ANC would be able to win a majority, thereby allowing it to write a majority-rule constitution. [xviii]

Sparks notes that the ANC objected to the party-convention idea, seeing the existing ‘non-white’ parties as apartheid puppets without support. Furthermore, given the presence of the old homeland parties, it would result in the co-opting of the ANC into a national forum of selected black leaders to discuss the country with the NP government. The ANC argued that to have legitimacy, the new constitution needed to be written by representatives of the people, determined by an election. These opposing visions made it difficult for negotiations to begin, in addition to the removal of obstacles to negotiations. [xix]

According to Allister Sparks (1994), the breakthrough was made by Nelson Mandela in January 1991 when he called for an “all-party congress” to negotiate the way to a constituent assembly. This presented a basis for compromise, there would be the multi-party convention that the NP was advocating. This convention would then negotiate an interim constitution under which a one person one vote elections would be held for a constituent assembly, as the ANC wanted. This assembly would then negotiate the final constitution. The constituent assembly would be able to draft the final constitution without restrictions; however, it would be bound by principles laid down by the multi-party convention, including the requirement of special majorities on certain issues. The ANC’s national executive committee endorsed this compromise on October 22, 1991, adding that no more than 18 months should pass between the end of the multi-party convention and elections, with an interim Government of National Unity ruling South Africa in this period. [xx]

Effects of the Inkathagate Scandal ↵

At the end of July 1991 and after the Inkathagate Scandal, where documentary evidence was released of covert funding by the state of Inkatha, De Klerk responded to the crisis. Besides justifying the funding on the basis that the programmes were initiated while the ANC was still banned; De Klerk stated that the government had no desire to be both player and referee of the transition. Furthermore, on the question of transitional measures, he confirmed the need for transitional measures to solve this problem [xxi] . After a cabinet reshuffle, De Klerk announced:

“Today, I wish to commit myself once again to transitional arrangements, which will ensure in a constitutionally accountable manner that the government is unable to misuse its position of power to the detriment of its discussion partners in a negotiating process. I have an open mind on alternative methods. However, any steps in this connection have to result from negotiation. As far as I am concerned, they may be the first item on the agenda of a multiparty congress.” [xxii]

The ANC’s national executive committee shortly met to review the situation, and believed that the government was at its weakest. It wanted to capitalize on this weakness by speeding up the process of consultation towards the formation of a patriotic front, as well as to move quickly towards an all-party congress to obtain as many compromises from the government as possible. The ANC then shifted its attention to these issues at hand. [xxiii] During the same period, Dikgang Moseneke, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) deputy leader, noted the party’s willingness to engage in a “pre-constituent assembly conference”. [xxiv]

An informal agreement already existed by the end of September 1991 that the all-party congress be held in November 1991. Agreed agenda items were:

“…the formation of an interim government or transitional arrangement; the principles of SA’s new constitution; the modalities of setting up or electing a constituent assembly or negotiating forum; and the role of the international community with special regard to sanctions.” [xxv]

On 25 September 1991, the PAC and the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) agreed to join the ANC at the all-party-congress and to push for the formation of a patriotic front. According to Mac Maharaj, there was consensus regarding the agenda of the patriotic front conference:

“In particular this means that the three organizations arrived at consensus with regard to the All-Party conference or the pre-constituent assembly conference. Consensus was arrived at regarding the modalities of transition, the agenda (for the congress or conference), which would include the items: interim government or transitional authority, modalities for constituting a constituent assembly and principles that would underpin a constitution”. [xxvi]

A Secret Pact ↵

At the end of September 1991 a conflict was taking place between the government and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) over the introduction of value-added tax (VAT). Cosatu was in opposition to this move because it would affect the poor the most. A strike would held on 4 and 5 November. [xxvii]

Certain pressures were to lead to a secret pact between the ANC and the NP. In a speech to the NP’s Cape Congress in October, before the VAT strike, De Klerk had said that he wished to tell all South Africans that the ANC was “in the clutches of radical and communist elements” and was not a friend. The president then went on to criticize the desire for sanctions and mass action, strikes, boycotts and protests. De Klerk also criticized the ANC’s notion of an interim administration which would “govern by decree in a constitutional vacuum” as “totally unacceptable”. However, after the VAT Strike, at the NP’s Transvaal congress in November, the president was heavily criticized for not having insisted that the ANC alliance renounce violence before it was unbanned. During this period, right-wing anger against the government was increasing coupled by increased support for the Conservative Party (CP). Furthermore, political violence had escalated after the signing of the National Peace Accord and this fed into pressures on De Klerk. [xxviii]

The ANC had become concerned about the dangers of weakening the NP too much. Therefore, despite criticisms being publicly voiced on both sides, ANC and NP delegations began meeting for confidential bilateral talks. This resulted in a secret pact between the two parties, which Anthea Jeffery (2009) argues paved the way for the multi-party negotiations which took place in December 1991. The existence of this secret pact came to public attention when the minutes of a confidential meeting between the ANC and the frontline states were leaked to the PAC. The minutes showed that the ANC and the NP agreed on the need for rapid progress in negotiations. Both planned to participate in an interim authority which would have control over elections, security, the electronic media, finance, and foreign affairs. Furthermore, both parties were then in agreement that a preparatory conference should be held to pave the way for multi-party talks. [xxix]

The Build-up to CODESA

Patriotic Front and announcement of talks ↵

More than 400 delegates representing 92 organizations met in Durban between the 25th and 27th of October 1991 to form the Patriotic Front, a loose-alliance of parties which had held an anti-apartheid position. However, it also included some black political structures that had collaborated with the NP government. A declaration was created from this meeting, outlining a joint program for a negotiated transfer of power. The Patriotic Front’s position was that an interim government was necessary for the transfer of power, as the government, it argued, was not suited to oversee the process of democratizing South Africa. At minimum, the interim government should control the security forces, the electoral process, state media, relevant areas of the budget and finance, and secure international participation. The Patriotic Front believed that only a constituent assembly, elected on a one person one vote basis in a united South Africa, could draft and adopt a democratic constitution. [xxx] Delegates at the conference also called on people to support the national strike, called by Cosatu against the introduction of Value Added Tax (VAT), on the November 4 and 5 1991. [xxxi]

Delegates at this meeting committed themselves to an all-party congress as soon as possible. They also agreed upon the conduct of members attending such a congress. Where all members agreed on an issue, they would follow the principle of “unity in action” but where there was no consensus members would act independently. [xxxii] The ANC then contacted parties with an interest in the negotiations. Separate meetings were held with the PAC, AZAPO, the Democratic Party (DP), homeland leaders, Mass Democratic Movement organizations and the NP. These consultations brought about the agreement that the negotiations be scheduled for 29 and 30 November 1991. Furthermore, the consultations decided upon the agenda for the meeting including: a climate of free political participation, general constitutional principles, the constitution-making body, an interim government, the future of the TBVC (Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, Ciskei) states, the role of the international community, and time frames. [xxxiii]

Hassen Ebrahim (1998) argues that the formation of the Patriotic Front had a significant impact on the negotiations, because “it changed the shape of the negotiating table and the political balance of forces in favour of the ANC.” The ANC’s demand for an interim government and a constituent assembly was entrenched. The government feared that the Patriotic front would gain the upper hand in negotiations. According to Ebrahim, this was the first time since the commencement of negotiations in 1990 that the government came to terms with the reality that it may have to give up the power it had enjoyed since 1948. [xxxiv]

Anthea Jeffery (2009) notes that the Patriotic Front conference on 25 October 1991 “marked the symbolic coming together of the ANC and PAC after 30 years of rivalry and the killing of many PAC and AZAPO members since February 1990.” Although the Patriotic Front was meant to unify parties in opposition to apartheid and did get together a significant number of parties, it was weakened by a few absentees. AZAPO (who was initially involved before it lost its status as co-convener after a falling out with the ANC and PAC [xxxv] ) and the IFP were absent, as well as smaller homeland parties from Bophuthatswana, the Ciskei and Gazankulu; while the Dikwankwetla Party of QwaQwa was described as having seemed hesitant in its support for the Patriotic Front. [xxxvi]

At the end of October 1991, the ANC and the NP were debating which parties needed to be invited to the congress. A broad agreement was made that all parties represented in parliament, including the leadership of homeland governments and independent territories, ought to be present. In terms of extra-parliamentary structures, the ANC, PAC, AZAPO, South African Communist Party (SACP), and the Indian Congress needed to be invited. [xxxvii] The NP met its allies on the 5th of November 1991 to prepare for the negotiations. Gerrit Viljoen was mandated to negotiate on their behalf. An interesting feature of this meeting was the presence of black leaders and some leaders who, except for Mangosuthu Buthelezi, were founding members of the Patriotic Front. [xxxviii]

Announcement of date for November ↵

On 13 November 1991, Nelson Mandela announced the scheduling of the first multi-party constitutional talks for the 29 and 30 November at the World Trade Centre in Kempton Park, Johannesburg. This convention was named the “Convention for a Democratic South Africa” (CODESA). [xxxix]

One may ask why CODESA was held in Johannesburg and not one of South Africa’s capitals. According to Roelf Meyer, “We tried to create "neutral ground" and that is the reason why the multi party negotiations were conducted outside any of the capitals. That also explains why no government structures were used for the negotiations.” [xl]

Preparation and issues ↵

Preparations for the convention were handled by a steering committee and a full-time secretariat. It was decided that the meeting be convened by Chief Justice Mr. Justice Michael Corbett, and two religious leaders, Johan Heyns of the Dutch Reformed Church and Stanley Magoba of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa. The steering committee faced a number of challenges, one being from the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), that only it, the NP and the ANC be responsible for managing the process of negotiation. The matter was resolved after a meeting between Viljoen and Frank Mdlalose, IFP’s national chairperson, where they resolved to include representatives of each of the 22 parties attending the talks. [xli]

The PAC also had concerns. Its national conference decided that the multi-party talks needed to be held outside of the country under an independent body, and threatened to withdraw their participation if their demand was not met. At the end of November, the PAC accused the ANC and the NP of reaching secret agreements, and thus violating the spirit of the Patriotic Front. Agreement was finally reached on the 20th of November, when the government, ANC, and IFP jointly announced that the negotiations had been rescheduled to the 20th and 21st of December 1991. Besides AZAPO and the HNP, all parties invited to the conference responded positively. The AWB and CP would also not take part in Codesa. An agreement was reached in the steering committee that the government would attend the talks as a separate delegate to the NP. The IFP objected to partisan church leaders being appointed as co-chairmen of the proceedings and it was thus agreed that both the preparatory and subsequent conferences would be chaired by judges Petrus Schabort and Ismail Mahomed. [xlii]

A preparatory steering committee meeting was held on the 29th and 30th of November 1991 and was attended by 20 political organizations and administrations. Parties present were: the government; the NP; the ANC; the SACP; a joint delegation of the Natal Indian Congress and the Transvaal Indian Congress; the DP; the PAC; the IFP; and the coloured and Indian parties in the Tricameral Parliament, the Labour Party, Solidarity, and the National People’s Party. Nine homeland parties or military councils representing all the homelands except KwaZulu were included. KwaZulu was considered adequately represented by the IFP. Cosatu was excluded on grounds that it was a trade union. [xliii]

The agreed agenda for the Codesa plenary consisted of general constitutional principles, a constitution making body or process, transitional arrangements or interim government, the future of the TBVC territories, and the role of the international community. A decision-making agenda was agreed to. The standing rules prescribed that where consensus failed, a principle of ‘sufficient consensus’ would be applied. [xliv] Codesa would have five working groups to deal with constitutional principles, interim government arrangements, a constitution-making body, the reincorporation of the independent homelands, and a time-frame for negotiations. Furthermore, a steering committee with one representative from each participating organization was established to draft a statement of intent to be adopted at Codesa’s first meeting. [xlv]

Ten minutes before the end of a steering committee meeting on December 16, 1991, the PAC repeated its concern that all decisions were subject to bilateral agreements made between the NP and the ANC. The PAC walked out of the talks in protest against the secret agreement between the ANC and the NP, and because of the necklacing of a PAC supporter in Munsieville (Krugersdorp). There were now 19 participants left in the negotiating process. According to Jeffery (2009), three were clearly part of the ANC alliance, while at least nine tricameral and homeland leaders would find it difficult to withstand pressure from the ANC. Thus, the ANC stood to control 12 out of 19 votes then the multi-party talks began. Ebrahim (1998) note that’s despite the exit of the PAC, the preparatory meeting was a success and all objectives were met. [xlvi] The preparatory talks went smoothly, according to Ramaphosa, because most organisations were ‘demonstrably committed to flexibility so that the process could move forward’. However, for the PAC this was because no real negotiations were taking place at all. They argued that the secret pact had already been made and all details of importance had been agreed upon before by the ANC and the NP. Furthermore, none of the other parties present could resist pressure from these two parties. DP leader Zach de Beer added that “Once you get agreement between the NP and the ANC you have a decision”. [xlvii]

During this period, the IFP demanded the KwaZulu government, the Zulu monarch, and the IFP be allowed to attend Codesa as three separate delegations. [xlviii] At the end of November, the steering committee established three working groups to prepare for the plenary focusing on Codesa’s statement of intent and founding charter, the organization of Codesa, and the broad process of negotiation. By the second week of December the presence of high level national and international observers had been announced. By this time, both the ANC and the NP had produced their draft proposals on the declaration of intent, which became controversial. The last paragraph of the ANC’s draft stated, “WE agree that Codesa will establish an implementing mechanism (which shall include the government) whose task it will be to determine the procedures and draft the texts of all legislation and executive and administrative acts necessary to give effect to the decisions of Codesa”. [xlix]

Up until this point, the NP had counted on the influence a multi-party structure could exercise over the government. They were thus unwilling to accept a clause giving Codesa the power to draft legislation to be rubber-stamped by parliament. However, Mandela warned that progress in the convention would depend on the decisions of Codesa being backed by the force of law. Without such a guarantee, the ANC was concerned that the negotiations at Codesa would not amount to more than a “talk shop”. The government, on the other hand, was not willing to compromise the sovereignty of parliament. The NP Secretary general, Stoffel van der Merwe, argued that this would not be a problem if decisions at Codesa were made with the consent of the NP. The ANC rejected this offer, as it would mean a veto for the NP. This issue was finally dealt with in a late-night bilateral meeting between the two parties on 18 December. The government agreed that Codesa could draft the legislation needed to give effect to the decisions made in the convention, and promised to do everything in its power to have these decisions implemented. [l] Umkhonto was also a source of disagreement between the NP and the ANC. The NP was resolute that the ANC’s arm wing be disbanded. The ANC however was determined to retain MK and the self-defence units. [li]

Growing tensions mounted between the ANC and the IFP mounted over the format of the constitutional negotiations. Inkatha had not accepted the Harare Declaration of 1989, and as the ANC increased pressure for an interim administration and elected constituent assembly, the IFP objected. Buthelezi claimed that the ANC was not working towards a multi-party democracy, but was rather attempting to speed up the process towards a constituent assembly, because this course had the “…greatest prospect for winner-takes-all politics”. The IFP desired a federal system which would divert power away from the centre, and many of its concerns were similar to those of the NP. This strengthened ANC suspicions that the government would collaborate with the IFP at the convention. However, by the time Codesa began on 20 December 1991, both parties had further blemishes by political violence, and prospects of collaboration between them had been frustrated. [lii]

On 19 December 1991, Inkatha announced that Buthelezi was withdrawing from Codesa because the Zulu King, Goodwill Zwelithini, had not been invited to the convention. However, Inkatha greed that it would still attend as a party. The white right wing also felt threatened by the developments. The AWB warned that it would “prepare for war” if the government failed to consider its demand for a boerestaat. The only party represented in parliament that did not attend these talks was the CP. Party leader, Andries Treurnicht, argued that the demise of the demise of the Soviet Union confirmed that nationalism was the strongest historical trend of the era. He then went on to warn South Africans who were striving for a unitary state of undivided South Africans, to come to their senses and to recognize the rights of people to self-determination. [liii]

Mandela thus found it necessary to reassure White South Africans that majority rule was not a threat and to argue that the ANC was ready to make radical compromises to ensure that. He proposed that this could be done by guaranteeing a block of white seats in the post-apartheid parliament for a limited period. Another option was that various political parties enter into an agreement to have a ‘government of national unity’ for a defined period after the first democratic election. However, such a compromise was subject to the fact that the ANC was not prepared to compromise on the principle of majority rule. Furthermore, Mandela denounced De Klerk’s new proposal of an interim government lasting ten years as a ‘trap’. [liv]

Constitutional principles prior to CODESA

ANC constitutional Principles ↵

The ANC produced its ‘Constitutional Guidelines for a Democratic South Africa’ in 1988. These were called a conversion of the Freedom Charter “from a vision for the future into a constitutional reality”. The guidelines envisioned that a constitution would not be a dry instrument, but would rather incorporate provisions for corrective action that guaranteed a redistribution of wealth, as well as promote non-racial and non-sexist thinking, as well as the practice of anti-racist behaviour. The Guidelines were briefly stated general principles, amounting to the demand for majority rule in a unitary, democratic and non-racial state. Sate policy would promote the growth of a single national identity, while recognizing the linguistic and cultural diversity of the South African people; the state and all social institutions would be under a constitutional duty to eradicate racial discrimination and to take active steps to eradicate the inequalities that it caused. Basic rights and freedoms were to be guaranteed, including the right of parties to take part in political life. [lv]

Advocating a unitary state meant the rejection of a federal system, endorsed in various forms by the NP, Inkatha and the DP. Sovereignty of the people was to be exercised through one central legislature, executive and administration. However, provision was to be made for the delegation of the government’s powers to subordinate administrative units. The guidelines included economic clauses that suggested an adherence to socialist or at least social democratic views. The state would have the power “to determine the general context in which economic life takes place and define and limit the rights and obligations attaching to the ownership and use of productive capacity”. There would be a mixed economy but the private sector was obliged to co-operate with the state in realising the objectives of the Freedom Charter. Only property for ‘personal use and consumption’ was to be constitutionally protected, although a clause mentioned the ownership of land, but not its constitutional protection. [lvi]

Affirmative action was mentioned as an instrument of economic redress, but how it would be enforced was not spelt out, other than briefly in relation to land reform. Apart from the abolition of all racial restrictions relating to land, affirmative action would be enforced in implementing land reforms, “taking into account the status of victims of forced removals”. Furthermore, provision was made for a charter protecting workers’ trade union rights to be incorporated into the constitution. [lvii]

The ANC published its constitutional principles and structures in April 1991. The constitution would be based on universal suffrage and a unified, non-racial, non-sexist nation. It would establish a bill of rights that would “acknowledge the importance of securing the minimum conditions of decent and dignified living for all South Africans” and include “basic human rights in relation to nutrition, shelter, education, health, employment and welfare,” Constitutional structures would include a strong presidency, limited to two terms; and a two-house legislature, one for national representation and the other for regional representation. Finally, an independent judiciary and constitutional court would interpret and rule on the constitutionality of proposed legislation. [lviii]

NP constitutional Principles ↵

The NP only published a formal statement of its constitutional proposals in September 1991. However, since February 1990, De Klerk and his ministers, especially Gerrit Viljoen, the Minister for Constitutional Development, had articulated several principles that were incorporated into the September statement. As David Welsh (2009) notes, the core of the model proposed by the NP was an elaborate system of protection for minority parties. The First House of a bicameral Parliament would be elected by universal franchise with an electoral system based on proportional representation. The Second House would be smaller and would represent the regions, each one of the nine suggested in the model being given an equal number of sets to be filled in regional elections. Each party winning a specified minimum amount of support in a regional election would be given an equal number of the region’s seats in the Second House. The second house was notably for minority protection, the assumption being that ethnic minorities would look to political parties to represent their interest. Therefore, legislation that affected minority or regional interests would require a higher majority to be passed, as for constitutional amendments. [lix]

The executive would provide further participation for minority parties. It would be a collective entity, known as the Presidency, consisting of the leaders of the three biggest parties. Chairmanship of the Presidency would rotate on an annual basis, and decisions, including cabinet appointments would be taken by consensus. [lx]

IFP Constitutional Principles ↵

As Welsh (2009) notes, Buthelezi began exploring federalism as early as 1974 and continued with the Buthelezi Commission and the KwaZulu Natal Indaba in the 1980s. Writing in 1990, Buthelezi warned black South Africans that the prospect of a government in a unitary state based on universal franchise frightened whites. Although the majority of black South Africans favoured this system, they needed to put South Africa first and ‘be prepared to look at a federal system, a canton system, or any other system in which the fundamental principles of democracy are … preserved.’ The Inkatha Declaration of 1990 listed the human rights that should underpin whichever democratic system is adopted, but added that provision should be made for minority rights, as long as it does not violate the principles of democratic government. However, as the situation and the IFP’s position changed in the negotiations, the tame statement of 1990 was succeeded by a more extreme demand for federalism. [lxi]

In early December 1991, the IFP released its first draft constitutional proposals, which were to be “capable of adaptation to either the unitary or federal structure of government”. The IFP’s proposals sought a division of executive power between a state president, and prime minister who would head a cabinet. For the legislature, there would be a lower house elected by universal adult suffrage through proportional representation. The Prime Minister would be chosen from the majority party of a coalition in the lower house, and would appoint the cabinet. A second house would represent the regions or states, “as well as any special interests which it is felt should be represented in the legislature.” Laws would require a majority in both house and consent by the President. The IFP was also in support of an impartial army whose allegiance lay to the constitution only, while the national police would be responsible to the Prime Minister. [lxii]

DP Constitutional Principles ↵

The Democratic Party, a descendant of the Progressive Party, held a record of support for civil rights and the rule of law, as well as federalism. It also has a longstanding commitment to liberal democracy. Its ranks of seasoned politicians allowed it to punch above its weight in negotiations, even though its electoral support was small, as seen in the 1994 elections. These seasoned politicians included: Helen Suzman, Colin Eglin, Zach de Beer and Ken Andrew. [xiii]Tony Leon was also involved, as an advisor to Codesa. He would be elected leader of the Democratic Party in 1994, and later become the leader of the newly formed Democratic Alliance (DA).

Proposals on Matters of Process prior to CODESA ↵

Besides constitutional principles, the process leading up to a new constitutional order was an area of debate and disagreement in the build up to and during Codesa. These ‘matters of process’ had to do with who would manage the transition period and how. Prior to the first Codesa plenary, there were four notable proposals: an interim government (ANC), a transitional authority (PAC and AZAPO), a transitional government (DP), and transitional arrangements (NP). Each proposal would lead to a different result. The IFP did not offer a proposal, while a member, Walter Felgate said, “We reject entirely the concept that a multiparty conference or all-party conference is being convened in order to establish an interim government”. The IFP argued that only a multi-party conference itself could arrive at a decision that there should be an interim government. [lxiv]

The NP proposal involved a multiparty structure where political organisations could influence government decisions. This would be similar to the President’s council or the “Great Indaba” that had been proposed by P.W. Botha in 1988. The multiparty structure could also involve various working groups on specific problem areas, thereby creating a form of power-sharing. The overall aim of the NP would be to permit broader participation in the transition. However, this would function within the current constitutional framework and the government would remain officially in control. [lxv] Furthermore, The NP saw Codesa as an informal interim government capable of transformation into a formal executive body. However, a (white electoral) referendum would be required before any major constitutional change. [lxvi]

The PAC and AZAPO sought a transitional authority whose participants would be approved by the liberation movements. Participants would be credible and neutral people who were mostly South Africans, but would exclude the government. International structures would need to endorse the make-up of the transitional authority. The authority would neither be involved in public administration nor implementing any apartheid laws. However, one of its primary functions would be to manage the security forces. It would have a rigidly-defined and limited mandate. The transitional authority would exist for a specified period only and would invite international monitors for elections. The overall aim of the PAC and AZAPO was to secure free and fair elections for a constituent assembly. [lxvii]

The DP envisaged a transitional government that would have its composition decided by the multiparty conference. It would include a “council of leaders” to advise the state president, and oversee state expenditure, the security forces and public broadcasting. It would also provide for participating local structures, supervise the reintegration of homelands, appoint specialist commissions to resolve particular issues, and broaden the representativeness of the judiciary, the public services, and the armed forces. Like the NP proposals, multi-party committees would advise cabinet ministers on the abolition of certain aspects of the constitution, and implement an interim bill of rights. The overall aim of the DP’s proposals was to secure an even-handed preparation for the elections. [lxviii]

The ANC envisaged an interim government representing only the major players. These players would have equal power and the interim government would be the supreme legal authority, requiring a transfer of power. The interim government would control the security forces, the public service, public broadcasting, and would design the electoral process of a constituent assembly. It would operate for a specified and limited period only. The interim government would create and implement an interim bill of rights. Its responsibility would also be to remove obstacles to negotiation and to oversee the transition. The overall aim of the ANC proposal was to affect a speedy transfer to majority rule. [lxix]

Hassen Ebrahim (1998) notes several points of general agreement. The IFP aside, it was agreed that an interim authority would be in place through constitutional negotiations. There was implicit agreement that the NP could not be both referee and player simultaneously. Finally, such an interim authority would last for as short a period as possible. [lxx]

However, differences were more substantial and were to dominate the negotiation agenda during the Codesa process. Essential questions had to be addressed. A concern of the NP was around the constitutional framework within which the interim authority would operate. Another question was whether an interim authority needed to be elected, as the DP proposed; and what authority it should have, whether it would act as a government with effective authority, or only have limited responsibility, as proposed in different ways by the NP, PAC, and AZAPO. [lxxi]

On 15 November 1991, there was a surprise shift in DP policy. The party’s national congress voted in favour of a proposal put forward by Colin Eglin advocating an elected constitutional conference to draft the new constitution. He argued for a four-phase approach: a multi-party conference phase, a constitutional conference phase (drafting the constitution), a referendum phase (a mandate from the people), and an election phase (implementation of the new constitution). [lxxii]

The ANC and the NP were also in disagreement prior to Codesa, on the duration of an interim administration and the format of the constitution-making process. Although the NP was now in favour of a transitional administration making the ANC co-responsible for administering the country, it also wanted this government to remain in place for a couple of years while Codesa drew up a constitution guaranteeing power-sharing, minority protection, and respect for the free enterprise system. On the other hand, if the final constitution was to be written by a constituent assembly, it wanted this body to be bound by firm principles which would ensure the inclusion of the above guarantees. [lxxiii]

The ANC wanted the interim administration to be limited to a brief time frame, only enough time necessary to give the administration influence over the security forces, the electronic media, financial transfers to the homelands, and the overall electoral process. After achieving this, the ANC desired an election for a constituent assembly to take place timeously. Furthermore, although the ANC accepted that the constituent assembly would be bound by certain guiding principles, these were to be broad as laid out in the Harare Declaration, and which would impose some significant checks on future executive power. Besides this, the ANC wanted the constituent assembly to be free to write a constitution as it deemed appropriate. [lxxiv]

CODESA 1 Plenary

December 1991 at World Trade Centre, negotiations begin. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

December 1991 at World Trade Centre, negotiations begin. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

The first plenary session of Codesa took place on 20 and 21 of December 1991 at the World Trade Centre in Kempton Park, Johannesburg. About 228 delegates from nineteen political parties and administrations attended the convention. The PAC was not in attendance as it had withdrawn from the negotiations a few days earlier. The CP, AZAPO, HNP and the AWB were also not in attendance. The nineteen political parties and administrations in attendance were the: NP, ANC, South African government, SACP, IFP, Labour Party, Inyandza National Movement, Transvaal and Natal Indian Congress, Venda government, Bophuthatswana government, Transkei government, United People’s Front, Solidarity Party, DP, National People’s Party, Ciskei government, Dikwankwetla Party, Intando Yesizwe Party, and Ximoko Progressive Party. [lxxv]

According to David Welsh (2009), the 19 parties and organizations at CODESA belonged to two categories. The first category numbered 15 could be described as ‘system’ parties and included the South African government, the NP, DP, IFP, parties from the Coloured and Indian houses of the Tricameral parliament and other homeland governments and parties. The second category was made up of four ‘anti-system’ organisations, the ANC, the SACP, and the Natal and Transvaal Indian Congresses (represented as a single organization). [lxxvi]

The distance between the ANC and the NP, as well as the IFP, remained as Codesa began. The ANC and NP’s intentions for Codesa were different. The ANC did not want to negotiate the constitution at Codesa, as that was seen as the job of a representative body. The NP hoped that a Constitution would indeed be negotiated at the convention but came to recognize the ANC’s unmoving stance on an elected-constitution making body. These seemed like two irreconcilable positions which would require a compromise. [lxxvii]

A Declaration ↵

A Declaration of Intent was signed as a preliminary, by 16 of the parties. David Welsh (2009) notes that it was a ‘bland document, long on ideals, but short on critical details’. Nonetheless, it committed signatories to a ‘united, democratic, non-racial, and non-sexist state in which sovereign authority is exercised over the whole of its territory’. The IFP and the governments of the ‘independent’ Ciskei and Bophuthatswana initially opted not to sign the declaration. Buthelezi and the Ciskei government suspected that the phrase, ‘an undivided South Africa’, prevented the option of a federal state. The Bophuthatswana government argued that it could not agree to a document that affected its status without the formal agreement of its government. The IFP and Ciskei administration were reassured through an amendment that ‘undivided’ did not rule out the option of federalism, and subsequently signed the declaration. The Bophuthatswana administration did not sign, hoping that they could secure a better deal. [lxxviii]

Among other issues, the declaration seriously committed all the parties to bring about a united South Africa sharing a common citizenship, to work to heal the division of the past, to try hard to improve the quality of life of the people, to create an environment helpful to peaceful constitutional change by eliminating violence and promoting free political participation, discussion and debate. [lxxix]

Proceedings and 5 ‘Remarkable statements’ at the Plenary ↵

The Chief Justice Michael Corbett opened the convention and two judges presided over it. Petrus Schabort, a white Afrikaner, was one of the judges. The other judge was Ismail Mohamed, South Africa’s first ‘non-white’ judge, a distinguished civil rights lawyer. According to Sparks (1994), the first session of the first plenary of Codesa was intended to be mainly a ritualistic event, “a television spectacular to impress the country and the world”. [lxxx] However, this was not to be the case.

I

Set speeches were delivered by leaders of each of the delegations at Codesa. According to Ebrahim (1998) [lxxxi] , five remarkable statements characterized the first plenary. The first was a speech by Dawie de Villiers, who spoke on behalf of the NP. He expressed ‘deep regret’ and officially apologized for the policy of apartheid, saying that “It was not the intention to deprive other people of their rights and contribute to their misery – but eventually it led to just that”.

II

The second statement was the compromise suggested by De Klerk where he indicated his government’s agreement to an elected constituent assembly provided that it would also act as an interim government. [lxxxii] He made a proposal to overcome the differences around the process of drawing up the constitution. He suggested a two phase-process. An interim constitution would be drafted by Codesa. In terms of the constitution, a fully inclusive Parliament would be elected, thereby sitting as a constitution-making body. It would produce the final constitution while incorporating pre-agreed “immutable constitutional principles”. The constitution would then need to be certified by the Constitutional Court for complying with the latter principles before passing into operation. South Africa would be governed by an elected transitional multiparty government between the election of the interim parliament and the ratification of the final constitution. [lxxxiii]

The state president had largely conceded to the ANC’s demand for an interim constitution and a constituent assembly. De Klerk said that the government was ready to begin immediate negotiations to amend the 1983 constitution to “make an interim power-sharing model possible on a democratic basis”. The government was moving towards an elected transitional government which would include “a newly constituted parliament representing the total population”. However, the government was not prepared to circumvent the 1983 constitution, and thus any changes to it could only be enacted after the approval of the amendments by the white, coloured and Indian population in a referendum. These proposals made by De Klerk early in the day, and the extent to which the NP had moved towards the ANC’s position in many respects, would be overshadowed by a later heated exchange between him and Mandela. [lxxxiv]

De Klerk further outlined some of the NP’s proposals for the new transitional government. The NP proposed this government as having a two-chamber parliament. The lower house would be elected by universal suffrage on the basis of proportional representation. The upper chamber would represent a number of regions all of which would have the same number of seats irrespective of population size, providing some protection for minorities. The presidency would be made up of the leaders of the three largest parties, and the power-sharing principle would be reflected in a coalition cabinet. [lxxxv]

III

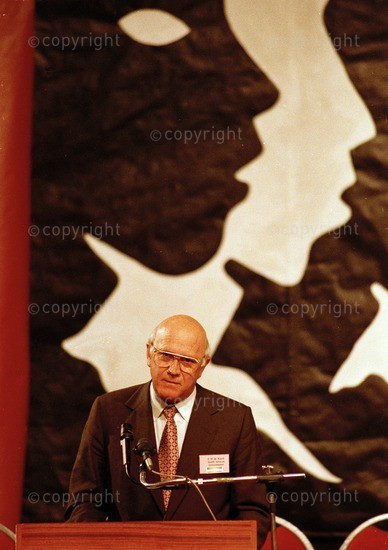

President F.W. De Klerk speaks at CODESA 1 plenary, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

President F.W. De Klerk speaks at CODESA 1 plenary, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

The third remarkable feature, according to Ebrahim (1998), was at the end of De Klerk’s intervention where he was scheduled to speak last. [lxxxvi] The first plenary session of Codesa was notable for the fiery exchange between Mandela and De Klerk. President De Klerk said that he had warned Mandela before signing the National Peace Accord in September 1991, that the ANC had broken every provision of the DF Malan Accord, which required the suspension of armed activities linked to the ANC and MK. De Klerk further stated that he had received assurances from the ANC that it would honour its commitments under the Accord, which it had not. The terms of the DF Malan Accord aside, and as Welsh (2009) notes, the truth was complex as it involved De Klerk’s denial of the government’s complicity in violence, and the fact that significant elements of the MK and state security forces were out of control. Furthermore, neither leader could easily acknowledge this. [lxxxvii]

Mandela had previously accepted De Klerk’s request to make the final speech on day one of Codesa. De Klerk then proceeding in marking a sharp attack on the ANC’s alleged violations of the DF Malan Accord. This he had done on the advice of some of his colleagues. On the eve of Codesa an intense discussion was held over whether the convention should take place or if the NP should postpone it until they had received a satisfactory undertaking from the ANC to implement the Accord. Kobie Coetsee had contacted the ANC, where they had allegedly promised to make rapid process in implementing outstanding issues. The NP’s policy group eventually reached consensus that it would be catastrophic to cancel Codesa, but that the issues was too serious to ignore. Coetsee was then instructed to inform Mandela that Codesa would take place, but that he should be aware that De Klerk would be highly critical about the ANC’s breaches of the Accord. Coetsee reported that this message had been relayed to Thabo Mbeki, who had promised to inform Mandela. Coetsee further reported that the ANC had expressed understanding for his concern at the delays and the fact that De Klerk would need to adopt a strong position. [lxxxviii]

However, Mandela never received the message and was enraged by the attack. De Klerk had described the ANC as the only party at Codesa with its own armed wing and secret arm caches, which had not been brought under control as required by the DF Malan Accord:

“An organization which remains committed to an armed struggle cannot be trusted completely when it also commits itself to peacefully negotiated solutions … we will have a party with a pen in one hand while claiming the right to arms in the other.” [lxxxix]

Mandela believed that he had been tricked into allowing De Klerk to speak last. Mandela walked up the microphone and launched a counter attack. He described De Klerk as ‘the head of an illegitimate minority regime’. Mandela noted that joint control of MK and its weapons would happen only when the ANC had an effective say in government, which would be “our government” and the army would be “our army”. He accused the government of ‘talking peace while at the same time conducting a war against us’. Furthermore, Mandela said that if De Klerk could not control wayward elements in the security forces or stop the sending of funds to Inkatha, “then he is not fit to be head of government”. [xc]

De Klerk did not respond. Both leaders were to calm down and shake hands. However, Welsh (2009) notes that this argument caused a breach between Mandela and De Klerk which never fully healed. He further argues that this episode dispelled the myth that the two parties were ‘in cahoots’. Rather it had been made clear that they were rivals, still separated by wide divisions. [xci]

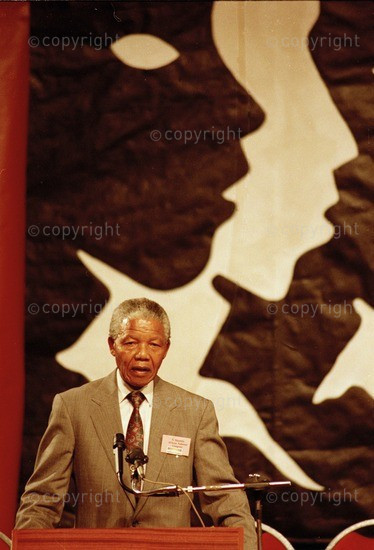

Nelson Mandela speaks at CODESA 1 Plenary, December 1991. Credit Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Nelson Mandela speaks at CODESA 1 Plenary, December 1991. Credit Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

An APDUSA journal of February 1992 paints a different picture of Mandela and De Klerk’s exchanges at the first plenary. APDUSA stands for the African People’s Democratic Union of Southern Africa. It is “a national political organisation which was established in 1961 by the Unity Movement of South Africa (UMSA).” A socialist and worker-centred party, it’s website notes that its “policy of Non-Collaboration with the ruling class and its agencies was coupled to this programme with the express purpose of developing the political independence of the working class” [xcii] . The journal addresses the English media’s “gleeful reporting” about Mandela’s outburst against his “Man of Integrity” in De Klerk. However, the English press failed to report that even before the end of Mandela’s speech, he began to change his tune. While the opening of his speech addressed De Klerk as the head of an illegitimate regime, he closed his speech by saying, “Because without him (De Klerk) we would not have made this progress.” [xciii]

The APDUSA journal provides further analysis into the interaction between the two leaders. It argues that the only truthful statement that came from the two days of the plenary was from Mandela, and not his opening or closing statements, but in his scathing criticism of De Klerk. The article noted that one would be left with the question of why the ANC was at Codesa negotiating with the government if that was its assessment. For the oppressed, for once, it argued, the ANC was saying something true and revolutionary, unfortunately though this took place “in that den of thieves, CODESA”. [xciv]

APDUSA argued that Mandela was not motivated by revealing the truth or disassociating the ANC from negotiations from the government. He was not angry because De Klerk’s allegations were true, but rather because De Klerk had attacked him without giving him prior notice. Mandela, as APDUSA argued, wanted to present a gracious occasion to the world, filled with praise, rather than a meeting truly concerned with the liberation of the oppressed. [xcv]

IV

Ebrahim’s (2008) fourth remarkable feature was the aforementioned Declaration of Intent. [xcvi] He notes that the Declaration was and is ‘an exceptionally important and historic document’. It was the first political agreement arrived at democratically and it made a break from the racially divided past. Furthermore, it committed all parties to the basic principles of genuine, non-racial, multi-party democracy ‘where the constitution is supreme and regular elections are guaranteed.’ In the South African context, the statement was revolutionary and represented in a sense, the ‘preamble’ to the first democratic constitution.

V

The firth remarkable statement came from the parliamentary veteran, Helen Suzman, where she demanded that a greater role be given to women to prevent accusations of gender discrimination:

“Here we are in this great hall at a momentous time, and I can’t believe my eyes and ears when I see the number of women in the room. As with racism, so with sexism – you can enact legislation, but despite this, racism and gender discrimination exists. When I look around, there are maybe ten out of 228 delegates who are women. Codesa, as a way forward must include more women”.

Ebrahim (1998) notes that Helen Suzman’s expression of disapproval incited immediate positive reaction from the participating parties, who from then on “made a welcome effort to ensure gender representivity”. [xcvii]

DP delegates: Colin Eglin, Zac De Beer and Helen Suzman at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

DP delegates: Colin Eglin, Zac De Beer and Helen Suzman at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Attending to Structural Issues ↵

After the negotiating parties had agreed and signed the declaration, five working groups and a Management Committee were elected and mandated to deal with specific issues, and it was resolved that the second plenary session of Codesa would take place in March 1992. [xcviii] The working groups established were made up of two representatives and two advisors from each negotiating party. [xcix] Each working group had a steering committee which dealt with the agenda and program of the work. Furthermore, each working group was to table its reports through its steering committee and would be directly accountable to the management committee. Agreements concluded would then be tabled at the next Codesa plenary for approval and ratification. [c]

A Management Committee, chaired by Pravin Gordhan, was set up to manage the Codesa process. It comprised of one delegate and one advisor from each of the parties. The Management Committee was assisted by a Daily Management Committee and a Secretariat. The Daily Management Committee’s members were: Zach De Beer (DP), Pravin Gordhan, Peter Hendrickse (Labour Party), Frank Mdladlose (IFP), Selby Rapinga (Inyandza), Roelf Meyer (NP), Zamindlela Titus (Transkei) and Jacob Zuma (ANC). Mac Maharaj and Fanie van der Merwe, the director general of Constitutional Development Services, headed the Secretariat. Van der Merwe was later replaced by Niel Barnard. The secretariat was responsible for the implementation of the decisions of the Management Committee. [ci] The CODESA Administration was headed by Murphy Morobe, who was helped by Dr Theuns Eloff and staff consisting of civil servants from the Department of Constitutional Development and the Consultative Business Movement. [cii] Codesa involve more than 400 negotiators representing nineteen parties, administrators, organizations, and governments. [ciii]

Working Group 1 was responsible for the creation of an environment for free political participation and the role of the international community. It was further divided into three sub-groups. Sub-group 1 focused on the reconciliation process including political prisoners, exiles and discriminatory laws. Sub-group 2 was responsible for political intimidation, the National Peace Agreement, crime and the security forces. Sub-group 3 focused on free political participation.

Working Group 2 was responsible for constitutional principles and the constitution-making body. Working Group 3 focused on the interim government. Working Group 4 was responsible for the future of the homelands and four sub-groups were created. Sub-group 1 was focused on getting the views of citizens of the TBVC states, and Sub-group 2 focused on citizenship. Sub-group 3 was responsible for the administrative, financial and practical implications of reincorporating the TBVC states into South Africa. Sub-group 4 focused on the political, legal and constitutional implications. Finally, Working Group 5 was given time frames and a responsibility to implement the decisions taken at Codesa 1. [civ]

The question of representation at Codesa was one of the first issues that the Management Committee had to deal with. It was required to consider applications by traditional leaders for membership, as well as for at least twenty other structures and organizations. One of these applications was from King Goodwill Zwelithini, of KwaZulu. De Klerk supported the right of the King to attend and participate but the ANC believed that his application should be considered in the same manner as those of other traditional leaders. Subsequently, the Management Committee agreed to establish a subcommittee to consider the representation of traditional leaders. [cv]

Jeffery (2009) notes that the ANC won significant concessions on the way in which Codesa decisions would be taken and the status they would have. It was agreed that Codesa would take its decisions “by sufficient consensus”. Some delegations had argued that this should require an 80% majority, but it was agreed that sufficient consensus had been achieved “when the degree of agreement is such that Codesa’s work is able to continue effectively”. The government interpreted this as meaning that any organization materially affected by a Codesa decision would need to be party to that consensus. Nonetheless, this was not made clear and the criterion was open to other interpretations. With regards to the status of decisions taken at Codesa, the ANC argued that they should automatically have binding legal force. However, the government opposed this, as it would invalidate the powers of Parliament. It was therefore agreed that both Codesa and the government would jointly draft any legislation needed to implement decisions taken at the convention, while the government would seek to ensure that Parliament enacted these laws. It was further agreed that all parties at Codesa would have a “moral obligation to implement any decisions” made by the convention. The ANC accepted this on the basis that it gave Codesa de facto, if not de jure power. [cvi]

Analysis of First plenary (CODESA 1) ↵

Codesa 1 played a significant role in laying the foundation for multi-racial discussions. [cvii] Hassen Ebrahim (1998) argues that “the importance of the first plenary meeting of Codesa cannot be over-emphasized, for it represented the first formal multilateral meeting to negotiate a settlement of the conflict in South Africa”. The convention resulted in a significant amount of confidence and enthusiasm, reflected in the behaviour of participating parties and in the views expressed by economists and editorials in the media. The editorial in the Financial Times of 3 January 1991, entitled “Progress in South Africa”, said:

“South Africa starts the New Year on a hopeful note. Progress in constitutional talks, coupled with tentative moves towards an interim government, represents the most important step in the country's transition to democracy since the release of Mr Nelson Mandela, the African National Congress (ANC) leader, nearly two years ago.

The agreement on a set of constitutional principles, endorsed by delegates attending the inaugural session of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), is in itself encouraging. While the principles adopted are taken for granted in western democracies, they represent a revolutionary change for South Africa, incorporating as they do commitments to an adult franchise and a multi-party system, a bill of rights and an independent judiciary.” [cviii]

However, not all organizations held such positive views of the first Codesa plenary. Various organisations criticized it before and after the plenary. Anthea Jeffery (2009) notes that the IFP expressed doubts about whether Codesa would provide an effective forum for genuine multiparty negotiations. Many smaller organisations told The Citizen newspaper that everything had been arranged beforehand and that “Codesa [had] been hijacked by the government and the ANC alliance”. An IFP official claimed that “the whole thing smacks of dirty tricks and collusion between the government and the ANC”. Members of the ANC and the SACP acknowledged privately that “the NP and the ANC/SACP alliance [were] able jointly to steamroller the IFP” at Codesa. [cix]

The CP and the HNP, who had refused to attend the convention, claimed that Codesa was biased towards the ANC. The CP leader, Dr Andries Treurnicht, argued that Codesa had no popular mandate for the decisions it was taking. Furthermore, a CP journal, Die Patriot, warned of the gradual transfer of power from the government to the ANC through the convention, thus betraying a trusting electorate and surrendering without a fight. Azapo, which also refused to take part in the convention, stated that “neither blacks nor whites were properly represented” at Codesa, the ANC had not acquired the majority support of blacks, while the NP had lost the support of most whites. [cx]

The PAC, which had pulled out of the convention in the planning stages, launched a “Death to Codesa” campaign and pleaded to take up various actions which would destroy the convention. Furthermore, as Anthea Jeffery (2009) outlines, both the PAC and AZAPO, together with other black consciousness (BC) organisations stated that they were intent on forming their own Patriotic Front to oppose Codesa. The Sowetan argued that the convention had already “turned black against black” and “white against white”. The newspaper spoke of a “great disaster – a new alliance, this time between the NP and the ANC, which would once again impose its will upon the country…That is a chilling thought because in that lie the seeds of civil war.” [cxi]

APDUSA was extremely critical of and opposed to the idea of the Codesa convention and the make-up of its participants, stemming from its moral, political and ideological stance as a radical left organisation. Codesa (1) was described as a

“…conspiracy hatched by the Imperialists (USA, Britain, Japan, West Germany, etc), giant local factory and mine owners, the banks, the Nationalist Party, the ANC and other lesser forces. The purpose of the conspiracy is to ensure that in the long and short term, the interests of capitalism and imperialism in Southern Africa are safeguarded through stability. As a by-product ANC officials who have political ambitions to occupy government posts, including the presidency, will be duly rewarded for their cooperation with the capitalists and imperialists.” [cxii]

It argued that from the perspectives of the poor workers and peasants, Codesa was ‘one more step along the road of betrayal politics of negotiations’, the organisational expression of that betrayal. It argued that this theme could be more clearly illuminated when one looked at the make-up of the participants of Codesa. The journal mentioned the “racist nationalists”, members of the “House of Shame” (Tricameral Parliament), Bantustan ‘leaders’, representatives of “giant monopolies” and those from countries like the USA, the Commonwealth and France on behalf of imperialism. [cxiii]

APDUSA argued that with the PAC boycotting, and since AZAPO/Black Consciousness Movement of Azania (BCMA), the New Unity Movement (successor of the Non-European Unity Movement, NEUM) and the Worker’s Organisation for Socialist Action (WOSA) would not be part of the convention, the only ‘liberation’ movement attending was the ANC-SACP alliance. It further noted and criticized the fact that Cosatu had wanted to attend Codesa in its own right and not as part of the alliance, but the government had disallowed it because it was not a political party. APDUSA further criticized the lack of democratic representation presented by the likes of the many homeland structures attending Codesa as well as tricameral leaders. [cxiv]

APDUSA criticized and questioned how Mr. Corbett could open the convention, as someone who occupied the position of Chief Justice of the Appeal Court in Bloemfontein, saying that “…he does occupy the chief position in a judiciary known for its naked racism…”. [cxv] Finally, APDUSA’s journal highlighted the New Unity Movement’s latest statement that “the conference [had] nothing to do with the promotion of the struggle for democracy, except to confuse it and destroy it.” [cxvi]

Codesa 1 lay the foundations for further negotiations around a transition to democracy and a new constitution. The plenary resulted in the signing of the Declaration of Intent, committing all parties to a united, democratic, non-racial, and non-sexist state, an important historical artefact and event. Codesa 1 established a substantial bureaucracy and five Working Groups to deal with negotiations on specific matters after the first plenary. The build-up to Codesa 1 and the plenary itself witnessed the disproportionate power held by the NP and government delegations, and the ANC, which produced discontent in some parties. A dramatic but important event occurred in the heated exchanges between Mandela and De Klerk, highlighting tension in their relationship as well as the importance of the unresolved issue of MK between the two parties. Important issues for all parties in Codesa 1, and to continue into Codesa 2, was the issue of constitutional principles for a new constitution, and an interim power structure. There was a lot of hope and optimism around Codesa 1 as could be seen by some party statements and newspaper articles of the time. However, not everyone shared this optimism, and there were other parties (as well as newspapers) to the left and right of the political spectrum who were more critical and sceptical of Codesa for different reasons. During the same time, the country was experiencing unabated violence, largely influenced by the government’s security forces, the ANC and the IFP; while support for the white right wing was increasing and this threat remained. As Codesa 1 laid the foundations for substantial negotiation in December 1991, the story continued in the first half of 1992 with the Working Group activity and the second Codesa plenary in May, where matters would soon come to a climax, at least as far as Codesa is concerned.

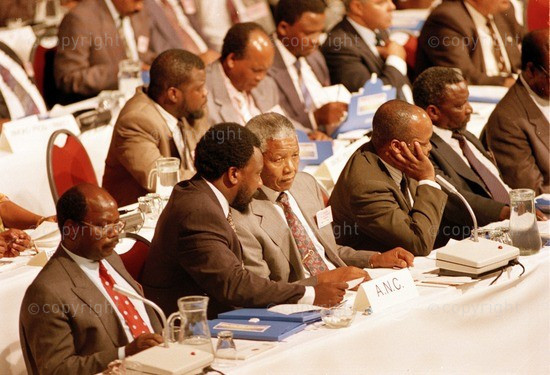

Cyril Ramaphosa, Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela and Jacob Zuma at CODESA 1, 20 December 1991.

Cyril Ramaphosa, Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela and Jacob Zuma at CODESA 1, 20 December 1991.

Press Conference, SACP at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Press Conference, SACP at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Negotiation at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Negotiation at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

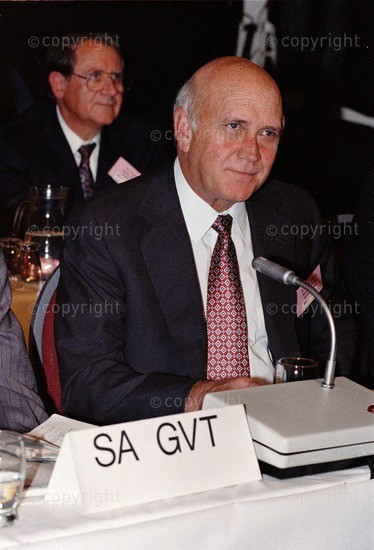

National government delegation at CODESA 1: President F.W. De Klerk and Pik Botha, December 1991.

National government delegation at CODESA 1: President F.W. De Klerk and Pik Botha, December 1991.

President F.W. De Klerk at opening of CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

President F.W. De Klerk at opening of CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

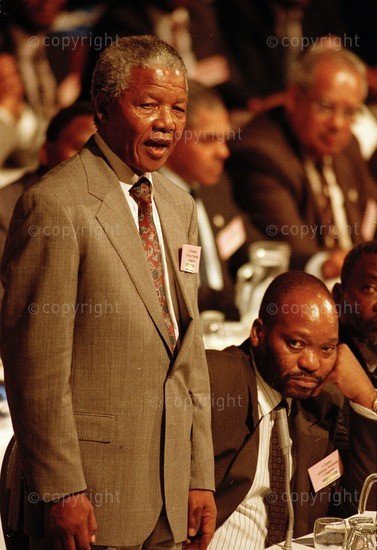

Nelson Mandela speaks at CODESA 1. Jacob Zuma sits alongside. December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

Nelson Mandela speaks at CODESA 1. Jacob Zuma sits alongside. December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online

ANC delegation at CODESA 1, December 1991. The middle three are Cyril Ramaphosa, Nelson Mandela and Jacob Zuma.

ANC delegation at CODESA 1, December 1991. The middle three are Cyril Ramaphosa, Nelson Mandela and Jacob Zuma.

Nelson Mandela at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Rodger Bosch Africa Media Online

Nelson Mandela at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Rodger Bosch Africa Media Online

Nelson Mandela addresses media at CODESA 1, December 1991. Next to him is Gill Marcus from the ANC, later to become South African Reserve Bank Governor

Nelson Mandela addresses media at CODESA 1, December 1991. Next to him is Gill Marcus from the ANC, later to become South African Reserve Bank Governor

Chris Hani and SACP delegation at CODESA 1, December 1991. Credit: Graeme Williams / Africa Media Online