In September 1915, the Union Government offered to raise an infantry battalion of Cape Coloured men for service in the First World War. A strict selection process was decided upon. Only men ‘of exceptionally good character, between the age of 20 and 30, minimum height 5ft. 3in., chest measurement 33 ½ in., unmarried and without dependants would be accepted for service.(Difford: 20). The Cape Corps War Recruiting Committee was formed with its headquarters in Cape Town. Notices were placed in the press announcing that recruitment was to take place. On 25 October 1915, the first recruitment station opened at the City Hall in Cape Town. The response was so huge that the assistance of the police was required to control the crowd. Only 22 recruits were enlisted on the first day as the vast majority did not meet the stringent conditions for enlistment. They were then sent to Simonstown for training and were joined by fellow recruits from Stellenbosch, Worcester, Port Elizabeth, Kimberley and various mission stations including that of Saaron and Mamre.

The number of men enlisted from rural areas and mission stations far outnumbered that of the city of Cape Town, as many of the would be recruits from the city did not meet the stringent physical requirements. Also many men who came to enlist at the City Hall were dissatisfied with the pay offered.

The Cape Corps in East Africa

The First Battalion of the Cape Corps embarked for East Africa on 9 February 1916 on board the H.M.T. Armadale Castle, arriving in Mombasa on 17 February 1916. For the first nine months, the battalion was occupied with tasks that supported the advancing British troops. This included guarding bases, patrolling roads, building of bridges, transport duties, hospital duties and various administrative tasks. Many succumbed to malaria in the first weeks of April 1916. The ‘C’ Company under the command of Captain Bagsawe and two platoons of ‘D’ Company and half of ‘B’ Company were sent to guard Taveta, where a railway line was being constructed and to build blockhouses. The detachment had to move through heavy swamps during the rainy season. Fifty percent of the detachment succumbed to malaria and had to be relieved by another company, who in turn also came down with malaria. By the end of April half of the Cape Corp battalion was in hospital or sick on duty.

The Rufji River campaign

In December 1916, The Cape Corps battalion left to partake in the Rufji River campaign. Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Morris, the battalion set off with four machine guns, a two-gun section of the Kashmir Mountain Battery, and a detachment of the Faridhkot Sappers and Miners. The main objective of this campaign was to cross the Rufji River and secure the area on the opposite bank against enemy encroachment. A dawn bayonet attack against the German position at Makalinso was launched successfully.

Kibongo

As the British advance followed the retreating German East African army, who attempted to delay the advance by stationing a field company at Mkindu, the Cape Corps was sent forward to reinforce a Nigerian Brigade at Mkindu. In January 1917 a column consisting of the Cape Corps, the Second Nigeria regiment and a two-gun section of the Kashmir Mountain Battery – under the command of Morris advanced on the German position at Kibongo. Morris used the Cape Corps as the central attacking force. The German army under Captain Ernst Otto offered a determined resistance, but were forced to withdraw by 12h00. At this point the heavy rain made further military movement impossible and many porters, members of the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC), struggled to deliver food rations through heavy swamps and mud. Both members of SANLC and the Cape Corps succumbed to malaria. By March only five officers and 165 men were fit for duty. Many were being treated in military hospitals in East Africa while some had to be repatriated to South Africa.

The next major military operation of the Cape Corps battalion was to join British and Belgian troops against German raiding parties led by Captain Max Wintgens who were attempting to enter British East Africa. By October 1917, the German threat had been eliminated, a feat in which the Cape Corps played a major role. Many members won awards for distinguished military conduct. In October 1917, the battalion had been re-organised and strengthened its numbers to 1 200 and ordered to assist the worn out British troops in the Lindi area of German East Africa. In November, the Cape Corps was leading the advance against the enemy and came under heavy fire at Mkungu. They were forced to withdraw 50 metres and dug in on a ridge.

The next action took place on the Makonde Plateau, where a German hospital containing 1 000 sick and wounded surrendered to a column led by the Cape Corps. The German commander, General Paul von Letow-Vorbeck moved with about 2 000 men towards Portuguese East Africa. After continuing with mopping-up operations the Cape Corps battalion was examined by a Medical Board. It was recommended that they be repatriated to South Africa. Although their battle casualties were not very high many were succumbing to malaria. On 20 December the battalion boarded the HMT Caronia back to South Africa.

From East Africa the Cape Corps went to Egypt, Palestine, Turkey.

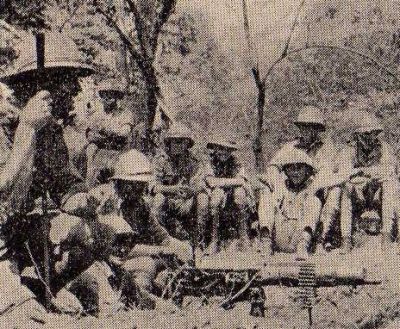

South African gunners in German East Africa. source: www.delvillewood.com

South African gunners in German East Africa. source: www.delvillewood.com

Back in South Africa:

On arrival back in South Africa, it was announced that, on account of their outstanding military record in East Africa, another battalion of the Cape Corps would be raised for service in Egypt. First the battalion needed medical attention and rest. Before sending men home for a period of recuperative leave they had to undergo strenuous medical tests for malaria. Two groups of three hundred men were entrained to Kimberley and Potchefstroom, while the remainder of six hundred men were sent to Jacobs Camp in Durban. They were to remain in quarantine for ten days, and only after their blood tests registered a double negative for malaria were they allowed to proceed home for a month’s recuperative leave. Those whose blood tests did not register negative for malaria were given further treatment and put on special diets of fresh milk and eggs. When they recovered they were sent home for a month’s leave.

By 20 February most of the men had returned to the depot at Kimberley. For the next month they were involved in training and preparation for the next phase in their service which was to be in Egypt. They undertook fresh training in gunnery, signalling, and bombing. Just before the end of March, it was announced that they would depart for Egypt in early April. The Battalion left Kimberley in three special trains for Durban on the 31 March. On 3 April they left for Egypt on the H.M.T. Magdalena.

The Cape Corps in Egypt

The battalion arrived in Port Suez in Egypt on 19 April 1918. Initially they were tasked with escorting duty at various prisoner of war camps. They were also involved in communication work. It was not envisaged that they would be involved in actual fighting and they had arrived without any equipment. This caused much dissatisfaction and their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Hoy, appealed to General Edmund Allenby, Commander of the British Empire’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), to allow them to participate in the fighting. Accompanying his request was a detailed memorandum that listed the battalion’s record in East Africa. General Allenby inspected the battalion himself and agreed to let them in the front line, on condition that they undertake further intensive training.

Cape Corps machine gun instruction. source: www.kaiserscross.com

Cape Corps machine gun instruction. source: www.kaiserscross.com

In Egypt the Cape Corps unit was faced with a very different set of circumstances than in East Africa. The army was far more professionally organised, the military campaign systematic and methodical, and auxiliary services such as hospitals and supplies excellent compared to East Africa. In the words of Difford, ‘We had left the amateur stage behind us and were by way of becoming professionals. A period of intensive training was commenced in musketry, bayonet fighting, the use of hand grenades, gas warfare and trench warfare. Officers were expected to be proficient in map-reading and topography.

In July 1918 the First Battalion Cape Corps (ICC) was assigned to 160th Infantry Brigade of the 53rd Welsh Division, one of several making up the EEF headed by General Allenby. Facing the EEF were three Ottoman Armies of 3 000 horsemen, 32 000 infantry, and 402 guns. The ICC entered the line on 19 August against the 53rd Division of the Turkish army, about ten miles north of what is today Ramallah. The battalion faced heavy artillery fire on a continuous basis for the next month.

Men of the Ist Battalion, Cape Corps(160th Brigade, 53 Welsh Division)- Palestine 1918. source: www.delvillewood.com

Men of the Ist Battalion, Cape Corps(160th Brigade, 53 Welsh Division)- Palestine 1918. source: www.delvillewood.com

Allenby planned a major offensive to commence in the early hours of 19 September and the unit was ordered to undertake reconnaissance and rehearsals in preparation for the offensive, by thinning out the front lines and concentrating on their attack positions. The 1/17th Indian Infantry Brigade was to be the advance guard, followed by the ICC. The ICC would pass through them, take Square Hill and then protect the right flank of the Brigade. The Cape Corps succeeded in their objective taking Square Hill in an attack that lasted from 18:45 on 18 September to 04:00 on 19 September 1918. They captured 181 prisoners, eight officers, and 160 members of other ranks, as well as an enemy field gun. The ICC lost one man, and another was wounded in the battle of Square Hill. Their next action involved the taking of KH Jibeit, a hill 700m north of Square Hill. They did not have artillery support and lost 51 men, 101 were wounded and one was taken prisoner. These actions were decisive in paving the way for Allenby to break through to Damascus and ‘knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war’.

Church parade of the 1st Battalion, Cape Corps, at El Arish, Egypt, after the battle. source: samilitaryhistory.org

Church parade of the 1st Battalion, Cape Corps, at El Arish, Egypt, after the battle. source: samilitaryhistory.org