This article was written by Ashley Schumacher and forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project

During the year of 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa six white English speaking women were brought together by their shared outrage against The Senate Act that was devised by the Nationalist Government. The Bill was implemented in order to remove voting rights of Coloured South Africans. The process to change the constitution that protected Coloured voting rights involved corrupt tactics used by the Nationalist government. To win their case, the Nationalists packed the two parliamentary houses with its own supporters. The disrespect of South Africa’s charter was the force that fueled the initial six women into the Women’s Defense of the Constitution League, today known as The Black Sash.

Although racial prejudice was not the original factor behind the formation of women, their ideology and organization transformed throughout the decades. This transformation was prompted by the league’s continual pursuit of justice in light of the growing human rights atrocities throughout South Africa during apartheid and beyond. This essay examines the Black Sash members’ peaceful pursuit for democracy in several stages, beginning with the organization of women and mobilization of the League and ending with the reestablishment of the organization post-apartheid. In all, the Black Sash as an organization was originally built with a conservative vision and within time was transformed into a broader humanitarian based institution. Today it fights for victims all throughout South Africa who still suffer from inequality in the 21st century.

The Women’s Defense of The Constitution League was initially formed on the principles of the constitution that were widely changed and/or ignored after the Nationalist Government came into power in 1948. At the time of formation the group was less concerned with the plight of people involved as they were with the corrupt alteration of the constitution by the Nationalist Government. The author Cherry Michelman, who wrote The Black Sash of South Africa: A Case Study in Liberalism published by the Institute of Race Relations, gave her opinion of the women. She says that the women’s strong beliefs and morals that compelled them to fight was in the ‘defense of liberty, conscience, freedom, unity, and intellectual integrity- all of which were embodied in the constitution’ (Michelman, 30). The constitution meant more to these women then just a set of rules; they were a way of upholding valued principles within their society. In Kathryn Spink’s book the Black Sash: The Beginning of a Bridge in South Africa, she says the organization was drawn to the use of ‘non-violent and peaceful means to promote justice and the principles of parliamentary democracy in South Africa”¦and to undertaking whatever other activities that may further the objectives of the organization’ (Spink, 4). In other words, the organization promoted a strong opposition to the destruction of the constitution by the National Party and opposed these issues via lawful means.

The first among many of the women’s protests against the Senate Bill began on 25 June 1955. The movement’s magazine documented the day like this: ‘Johannesburg saw 2,500 women march in silence from Joubert Park to the city hall’ (BS Magazine, 6). This was mostly due to the mobilization of the initial six women- Ruth Foley, Jean Sinclair, Jean Bosazza, Helen

Figure 1 Cape women stand in mourning over a book draped with a black sash, symbolising the Constitution, February 1956.

Figure 1 Cape women stand in mourning over a book draped with a black sash, symbolising the Constitution, February 1956.

Thompson, Tertia Pybus, and Elizabeth Mclaren who began to telephone others, who then reached out to others to join. Black Sash member Mirabel Rogers also documented in her book, The Black Sash: The Story of the South African Women's Defense of the Constitution League, that the women published a ‘we cannot stand by and do nothing’ manifesto that appeared in the press at every corner of the Union (Rogers, 16). Unfortunately the Senate bill was signed despite the opposition from the group of women. But the fight was not over between the women’s organization and the government. The protest continued calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Strijdom. On 28 June 1955 the women stood 48 hours outside Union Buildings waiting for the prime minister in Pretoria to meet with them. Though he failed to make an appearance the women decided to keep the constitutional issue in the public eye. The strategy in which the Black Sash initially and continually employed was explained by Rogers. She says, one of the first protests began ‘On Monday July 18th in Pretoria”¦when four women took up their places silently inside the entrance used by the ministers, wearing the shoulder sash of mourning”¦day in and day out [they stood] until parliament met again.’ (Rogers, 43). The women sought to haunt the members of parliament by following them wherever they went and reminding them of their opposition by dawning their black sashes. The Sash served as a symbol for the death of South Africa’s constitution. The league continually employed this strategy, which gave the organization the title ‘Black Sash’(See figure 1).

The failure of the initial protests by Black Sash women was a time in which many conservative members began to fall away. A majority of the members left the group due to other life matters. This enabled the leadership of the organisation to establish a clear vision of what the league stood for and focused on. In 1956 Jean Sinclair, one of the founders of the organisation, steered the organisation away from a focus on only a certain number of legislations to all legislation that sought to take away rights from non-White groups. The league voiced that, ‘Whenever a section of our population is threatened with discrimination, injustice or loss of liberty, we shall protest’ (Spink, 48). In time, the remaining Black Sash women were better organized under the new established aim of the organisation, in which they turned against the apartheid government. There was still a struggle to get most of the women to agree with the newly found objective, especially since the League was still widely conservative at the time. Defending the rights for Black groups was not exactly ideal for many of the socially conservative Sash women.

During the early period of identity searching within the organization throughout the 1950s, the majority of the members were generally unconcerned about or unwilling to participate in the fight for the rights of African citizens in South Africa. This can be due to many factors; one includes the women’s lack of education on African issues. Many of the Black, Indian, and Coloured issues were shielded from the public White population by Nationalist government. Another reason can be due to social barriers that were rarely challenged in the widely racial South Africa. Association with African people could lead to ostracism and abuse by the society in which the Black Sash women belonged. Though further reasoning can be due to the concern that existed among some of the Black Sash members, that if they‘filled [their] ranks with colored and blacks who had no vote, [they] would lose [their] strength’ (Spink, 58). Many parliament members refused to even speak with the Black Sash women if they had any members aside from the White race in their league. This fact concerned the Black Sash less in the 1960s when the organisation allowed all races to join. Unfortunately, the membership dues at that time were nearly unaffordable by African citizens and the group was pigeon holed into an all White organisation until the end of apartheid. As understood by these examples, the startup of a clear vision for the organization was a struggle due to the members’ lack of concern about the people they were supposedly supposed to be fighting for. However this stigma did not remain, as the Pass laws in that late 1950s became severely enforced and the Black Sash stepped up to join the fight against them.

According to Black Sash member Mary Burton who joined in 1963, the ‘pass laws’ were ”¦ sections of the urban areas act which restricted rights of Black African people to move freely about the country of their birth’ (Burton, 130). Not only men but women were now required to carry pass books when traveling. In light of this fact the arrests of female African citizens hit an all new high due to the pass laws. So much so that the Black Sash women were moved by the lack of justice, prompting them to implement bail funds for convicted women. During this time in 1958 the Black Sash women also opened its first advice office in Cape Town to provide legal aid services for the victims of pass laws. Spink explained that the ‘philosophy behind the advice offices was to enable people to understand what the law was, to enable them to make choices about how they wished to act and to support them in their chosen action’(Spink,75). The advice offices sought to aid victims of apartheid legislation within lawful means. Though because the Black Sash women were not very keen on the legislation that effected African people they looked for help from other African women’s anti-apartheid organisations/ supporters. These include the African National Congress Women’s League (ANCWL) and Cape Association to Abolish Passes for African Women (CATAPAW), among other organisations and townships. The opening of the first office in cooperation with other anti-apartheid organisations/ supporters became a major milestone in the Black Sash organisational development. For it would ‘open up a second dimension to what was fundamentally a political pressure group, [to] a ‘service’ aspect’ (Spink, 64). The women were now not only talking, protesting, and writing of change but making an effort to understand and help the people who would mostly be effected by any change in an apartheid society. For a White individual to reach out beyond a barrier of society and work side by side with Black individual or vice versa was a statement in itself. For this was the beginning for Black Sash members to learn what life was really like for African citizens.

Following the opening of the first Black Sash advice office, other members started to follow pursuit by opening up offices throughout country. Between the 1960s and 1970s the offices were packed with thousands of people seeking help from unjust laws regarding forced removals of communities, segregation, discrimination in education and workplace, and health care. These were only some of the issues among many that effected the African population. The women in the offices were constantly learning of laws that came against Africans, their effect, and how to fight them. A productive strategy that many members undertook were sit-ins in the commission courts. Well throughout the 1980s this exercise provided an insight into the political reality for South African nonwhite citizens during the century. The sit-ins were said to be useful because ‘the information the organization gained by this means became the starting point for various strategies employed to force the government to act, strategies in which the essential ingredient was public knowledge’ (Spink, 79). The knowledge gained from watching the court systems helped give insight into the reality of African citizen’s hearings and the injustice they faced. This unfortunate fact gave the Black Sash women the information they needed to strategize and protest against such unlawful acts. One of the main strategies from the beginning was applying pressure to the government by educating the wider public by means of media via documented protests, pamphlets, Black Sash newspapers, and informational meetings.

Throughout the late 1970s, the Black Sash and other anti-apartheid organisations were under increased pressure due to the political environment in South Africa that changed dramatically. Many opposition groups started to mobilize intensively, following the Soweto riots of 1976. The student riots were sparked by the issue of the Nationalist government enforcing a law that required Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in African schools. This was a turning point and crucial year in South Africa where there was a nationwide spread of violence throughout the country. Many Africans started to fight against the system knowing that peaceful protest was no longer effective. One of the popular groups included the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC slowly started to support the acts of violence that escaladed well into the 1980s. During this time many of the Black Sash members became very active not only in the advice offices but out in the African communities that were considerably oppressed. At this point in the anti-apartheid struggle it was hard to ignore the violence and injustice that went on in the courts, offices, and communities that the Black Sash members were involved. Within this tumultuous time, the Sash kept considerable records of most of the events that took place. They were keen on monitoring field events and keeping records of what was witnessed and happening within the lives of many African people. The sense of urgency and mobilization within the organization at this time brought in more members to join who were tired of the lack of transparency from the Nationalist Government.

The women who joined the organisation were exposed to and/or became aware of the injustices done against African citizens. Out of the group of members there were those who felt led to take a stronger stand against apartheid. One of these women include Molly Blackburn who joined the Black Sash in 1982 after being exposed to life in the black townships. She joined after an advice office opened in Eastern Cape, an area in which the ‘racial divide was potentially at its most expansive’ (Spink, 164). Blackburn came from the Eastern Cape and found herself more interested with doing hands on practical work in order to understand the organisation and the plight of issues that it was involved in. During the time Blackburn was thinking about joining the Black Sash, she and Sash member Di Bishop were elected to the Cape Provincial Council. This was a great asset to the Black Sash as every parliamentary candidate had a partner from the Provincial Council. The council opened up numerous doors to important contacts for the Sash women. These contacts proved useful when on July 1981, Sash member Di Bishop took Blackburn to the Black township of Langa outside of Cape Town. A police raid had taken place the night before where the Black Sash advice office asked Bishop to help an 80 year old man who had lost his daughter and grandchildren in the course of the raid. Blackburn promptly recorded the results of their findings: the arrest of the man’s daughter, the experiences of the courtroom and the conditions in Langa. In an article entitled ‘Life Among the Evicted’ Spink says that, ‘the fact that [Blackburn] was a MPC opened up additional avenue for ‘conscientousing’ the public’ (Spink, 166). Blackburn was seen as an admired character of the Black Sash for her efforts in not only publicizing events that took place in townships like Langa but also her international contacts and court testimonies of police brutality and violence in 1984. In 1985 during the government’s announcement of a ‘State of Emergency’, the presence of police intensified in black communities. The individuals who were working with the communities were arrested. This included Blackburn who in 1985 was caught in one of the townships.

Blackburn was an example of a member like others who were willing to take that risk for the greater good of the people she was serving. Many White South Africans found this fact threatening about the Black Sash organisation because ‘the Black Sash was undoubtedly seen as a group who went against their own self-interest.’(Spink, 215). The Black Sash was more interested in bridging together communities then dividing them. Blackburn was one of these with progressive attitudes because nothing stopped her from continuing on in fight for equality and freedom for the African people, which many say led to her death in 1985 when she was killed in a car accident. Many suspect a government planned attack. Though whatever the case was, Blackburn made a mark on the organisation’s history and direction it would face in the future. During the funeral Blackburn was quoted:

‘White South Africans think that the gap between black and white is too wide to be bridged”¦I don’t think this is so. If you stretch out a loving hand, somewhere on the other side a loving hand will take it, and that will be the beginning of a bridge’(Spink, 184).

Like Blackburn, Di Bishop also felt that humans were equal regardless of the color of skin. The only thing that mattered was that they were people who were all fighting for one cause. However, not all Sash women felt the same way, especially in regard to joining communities or organisations’ that they felt jeopardized the organisation’s name.

The lack of alignment in the Black Sash with other popular organisations was brought into question in 1955 when other anti-apartheid leagues such as Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) and the Congress Alliance came forward to affiliate with the Sash. Because the Sash members were widely conservative at the time, the majority refused to join any organisation that came against their ideals or skewed the Sash image. Historian Cherryl Walker says that ‘most members of the Black Sash looked askance at the congress alliance as a radical and potentially subversive organization. As originally conceived, the Black Sash was essentially a conservative organization. It was formed to protect the constitution, not to seek radical change; its members were anti nationalist but certainly not pro majority’ (Walker, 174). The Black Sash was mainly conservative in the startup of the organisation in 1955. Though in 1956 as many of the conservatives started to fall away, the more liberal core of women came forward to lead the organisation, as said earlier. The growing liberalism in the group along with the changing tide of apartheid opened doors for more women to join. Though how ‘liberal’ the majority of the group was and how far they were willing to go for the cause was questioned by many anti-apartheid supporters and organisations throughout the apartheid era. Especially because the Sash gave several denials to aligning their selves to any of the organization groups.

Although there were women like Molly Blackburn and Di Bishop who championed the way for white support on the ground and in the media for victims of apartheid, many others were not as willing to do the same. Spink says, ‘among others engaged in the struggle who were prepared to talk, there were some who saw the Black Sash as liberal in a pejorative sense of being prepared to recognize and criticise what was immoral and unethical but not prepared to walk the last mile, not quite prepared to become involved to the extent that the ‘oppressed people’ would like them to be’ (Spink, 259). The common criticism of the Black Sash as a whole was that although they supported freedom and democracy by participating in field work, commission courts, advice offices, and protests, they were not willing to go further to promote such ideals as many of the anti-apartheid organisations were doing at the time of 1970s and 1980s. The reasoning behind this had a lot to do with how much the legislation actually effected the group of Black Sash members compared to the non-white citizens in everyday life.

In a women’s news journal article called ‘Off Our Backs’, the article says regarding women organisations during 1913-1977,

‘Whereas political organizations of white women in South Africa, such as”¦the Black Sash, have tended to be historically isolated and fragmented, the position with Black women’s movements is somewhat different, largely, I think, because their organization has always been a response to their own experienced material reality”¦these were not women talking abstractly of rights and morality, but women very really and specifically threatened on the basis of their class, their race, and their sex’ (South African Women Organise).

The oppressive legislation did not directly and harshly infiltrate Black Sash members’ lives which made it easier for a majority to pick and choose what they wanted and did not want to do during apartheid. For example the Black Sash’s lack of support for violence was easier for them to cope with in comparison to other strong African organisations such as FEDSAW, UDF, or all of those under the Congress Alliance such as the ANC. These organisations that were heavily involved in the liberation struggle were quick to criticize the Black Sash because of the Sash members’ refusal to further align themselves with the anti-apartheid organisations and share in the risks and benefits that could be acquired though participation. Although the Black Sash did not align themselves with the more radical organisations they did work closely with what they considered‘safe’ organisations such as the Free the Children Alliance and Human Rights Commission among

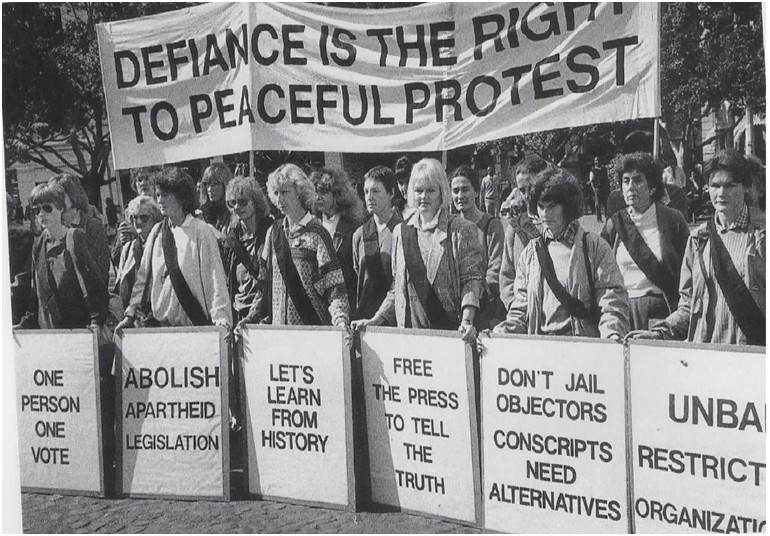

Figure 2 Illegal multiple stand in support of the Mass Democratic Movement's defiance campaign, Cape Town, August 1989.

Figure 2 Illegal multiple stand in support of the Mass Democratic Movement's defiance campaign, Cape Town, August 1989.

others.

After 1994, the installation of the new government headed by Nelson Mandela, brought questions toward the organisation’s new role in post-apartheid society. Many Black Sash members argued to disband considering the original mission of fighting the constitution was met. Though others opposed the decision saying there were still many issues South Africa faced in the times ahead. Sheena Duncan, president of Black Sash from 1986 even said ‘Any post-apartheid government is going to have tremendous challenges to face if it is to be able to even begin to meet the expectations of the people’ (Duncan, 18). And the country did struggle with promoting peace and equality economically, socially, and politically. This fact allowed for the Black Sash advice office doors to remain open well into the 1990s and present day as there were still many issues that citizens face in Post-apartheid South Africa.

The organization kept the vision of supporting and monitoring human rights atrocities through nonviolence in South Africa. The organization is currently staffed by employed personnel and headed by a board of trustees. On the Black Sash website the trustee’s board quoted a statement in November 2012:

The organization kept the vision of supporting and monitoring human rights atrocities through nonviolence in South Africa. The organization is currently staffed by employed personnel and headed by a board of trustees. On the Black Sash website the trustee’s board quoted a statement in November 2012:

‘The Black Sash believes that at this time in the history of South Africa, and of our organization, the most urgent issues to be addressed are the on-going poverty and inequality afflicting the lives of the most vulnerable members of our society. South Africa cannot be free as long as the majority of its people continue to live under conditions of deprivation and injustice. We are affected and diminished by this....We therefore commit ourselves to foster, support and encourage community initiatives to monitor, record and analyses the socio-economic conditions prevailing in South Africa.’(Black Sash Official Website)

Today the Black Sash takes part in promoting rights-based information, education and training; community monitoring; and advocacy in partnership (Black Sash Official Website). For example, a huge component of education includes the publishing of historical archives and activities from advice offices and field work of the Black Sash. These sources are now readily available all throughout South Africa and allow for people to understand the plight of issues Africans had and still today face in the 21st century (Black Sash Archives; UCT Library).