Abstract

Johnny ‘Mbizo’ Dyani was a jazz musician who performed during the apartheid era. He played for almost his entire career in exile before passing away in West Berlin, Germany at the age of 39. Dyani actively fought against the apartheid regime through the medium of music and assisted the African National Congress (ANC) by performing at events in Africa and Europe. Johnny Dyani is best known for his membership with the Blue Notes, an interracial band that performed for a short period in South Africa before moving to Europe.

Key Words

Johnny Dyani, jazz, music, double bass, apartheid, African National Congress, Blue Notes, exile, Islam.

Introduction

Johnny Dyani is widely believed to have been born on 30 November 1945 in Duncan Village, a township in the city of East London in South Africa. This date was widely believed because Johnny stated this date when he was interviewed. However, research in the records of the Home Affairs Office found by his biographer suggests that Johnny was actually born in on 4 June 1947 in Zeleni Location near King Williams Town.[1] The obscurity around his birth reflects how mysterious Johnny Dyani was and how little the world truly knew of him.

The clearest aspects of Dyani’s life are his musical prowess, his influence on South African jazz, and his efforts to stand against the apartheid regime. He not only revitalised and revolutionised South African jazz by collaborating with the artist Abdullah Ibrahim, but also utilised the medium of music to fight apartheid by bringing global awareness to the evils of apartheid. Despite his brilliant work, Dyani remained frustrated with his situation and apartheid which was reflected in some of his aggressive outbursts and most likely a cause of his substance abuse. Dyani would not be satisfied with his work until apartheid was brought to an end, which unfortunately he did not live to see. While Dyani may have been unsatisfied with the other exiled musicians selling out for money, Dyani remained committed to creating true South African jazz music and using his talent to contribute to the struggle against apartheid.

With the help of Lars Rasmussen and his findings at the Home Office in King Williams Town, Dyani’s true birth date is now known and that he was the son of Ebenezer Mbizo Ngxongwana and his wife Nonkathazo. Dyani was believed to have been a triplet, but both his siblings and his mother tragically died during childbirth. Out of fear that Dyani too would die, the people surrounding him had Dyani baptised immediately and he was named Johnny. This is why Dyani has only one name instead of both an African and a Christian name like many other Xhosa children had at the time.[2]

It is unclear whether or not Dyani knew about his adoption prior to his departure from South Africa. His step-brother and nephew, Fikile Dyani, thought he did not know. His biographer, Rasmussen speculates that he learned the story when he was in Europe through a phone call or letter. This means that Johnny believed his biological mother was Minnah Dyani, who was actually his stepmother. His biographer speculates that it was her who told Dyani the tragic story, and the news must have shaken him to his core.[3] This was one of many factors which may have contributed to Dyani’s frustration as evidenced by his occasional aggressive outbursts as well as his substance abuse.

The Dyani family adopted Johnny and raised him for the first part of his life in Duncan Village, a township within East London.[4] It should be unsurprising to hear that the Dyanis were a musical family and had a piano in their house, which all the children used to play. Johnny showed a passion for music early in his life as he also played two self-made instruments: a one-string bass made from a tea box and a stick, and a guitar made from an oil tin.[5] Johnny played on the streets which exposed him to kwela music – the style which gained incredible popularity during the 1950s. He was undoubtedly influenced by this type of music in his early years and this played a key role in developing him as a musician and inspiring him as an artist.

Johnny showed musical diversity in his early years as he played drums and trumpets with the boy scouts and a church boy brigade, as opposed to playing the double bass which he became renowned for in his professional career. Dyani found his love for bass when he came into contact with other artists who would later become famous while living in Duncan Village. As a milk delivery boy, Johnny would go to the homes of famous South African artists Tete Mbambisa and Pinise Saul where he would play the instruments after delivering the milk.[6]

The influences of great South African musicians may have been an aspect which spurred Dyani’s passion for music. According to Dyani’s close friend Pallo Jordan, growing up near the likes of Tete Mbambisa and starting his career at an early age were the factors that allowed him to become a profound and thoughtful musician during his exile. Dyani made his stage debut with Mbambisa in a quintet that toured the coastal cities.[7]

Joining The Blue Notes and Leaving South Africa

Johnny Dyani’s passion for music and desire to grow as an artist were clear indicators that he was to achieve a bigger role within South African music. Dyani’s path was changed when he came into contact with the Blue Notes, an interracial modern jazz band. The Blue Notes were founded and led by Chris McGregor, who was the son of white missionaries. McGregor, along with Mongezi Feza, Dudu Pukwana, Nikele Moyake and Louis Moholo, all played in festivals in Cape Town and were brought together through their shared affinity for leaders of the modern jazz movement in the United States. The likes of Charles Parker and Dizzy Gillespie influenced the Blue Notes members with the be-bop style, which they incorporated into their own style of music.[8] Johnny would later say that he believed Africa was the source of all inspiration to great jazz music. When the Blue Notes were playing a gig in Duncan Village, a brave young man requested to join in practicing with the band. The members allowed him to perform and realised from the instant he began to play that this was no mere boy, but rather an incredibly talented musician. Dyani became a member of the band that same day.[9]

In late 1963, it became clear that the Blue Notes would have to leave South Africa for two reasons: first, because travel in the townships had become too dangerous and interracial groups were not allowed to perform together according to the 1963 Publications and Entertainments Act No 26; and second, because Dyani and the other members of the Blue Notes could not reach their full potential under the oppression of apartheid.[10] In 1964, the Blue Notes were invited to the Antibes Festival in France. Seeing their opportunity to grow as a band and avoid the dangers looming in South Africa, the band made efforts to leave the country. The apartheid government made it almost impossible for a black South African to receive a passport and the only way to do so was for white intervention in order to facilitate travel. After being invited to the Antibes Festival, Chris McGregor’s partner, Maxine, made the passports and leaving South Africa possible. The band fled South Africa in 1964 to seek musical and political freedom from the apartheid government.[11]

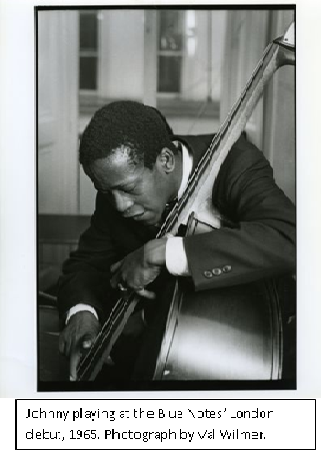

Johnny playing at the Blue Notes’ London debut, 1965. Photograph by Val Wilmer.

Johnny playing at the Blue Notes’ London debut, 1965. Photograph by Val Wilmer.

Once in Europe, Dyani’s trajectory as a musician was thrown forward faster than anyone, and perhaps most of all Johnny himself, could imagine. After playing in the Antibes Festival in 1964, Dyani and the Blue Notes were left stranded and relied on busking to survive. The 1963 Publications and Entertainments Act No 23 had just been passed in South Africa which forbade interracial bands, and as a result ruled out the possibility of returning home.[12] The Blue Notes landed an engagement at Club Africana in Zurich, Switzerland thanks to Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim), who was living there at the time. Dyani was given a possibility he did not have the luxury to in South Africa: the ability to travel. And so he travelled – between Zurich and Geneva where he played in bars between 1964 and 1965, before the band settled in London in April 1965 playing at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club.[13]

In 1966, the Blue Notes effectively broke up. Johnny left for Rome to play alongside American saxophone player Steve Lacy. Later that same year, Lacy invited Dyani and Louis Moholo to join him and Enrico Rava to play in Argentina. Whilst there, the four of them recorded The Forest and the Zoo which showcased their incredible potential and abundant talent. However, they missed a certain factor: there was no audience for their music in Argentina. Unfortunately, the Argentinian people did not have an affinity for their style of jazz music, so the group split. Steve Lacy returned to New York and Enrico Rava returned to Europe, leaving Moholo and Dyani stranded in Argentina without enough money to return to London.[14] Dyani and Moholo were aided by the remaining Blue Notes members and returned to London in 1967, where they played for the new band titled The Chris McGregor Sextet.[15]

In the years he lived in London following his trip to Argentina, Dyani had transformed from the boy that left South Africa to a free-thinking, mature adult. In an interview with Pallo Jordan, a friend of Dyani, Jordan reflected how Dyani had changed after his trip to Argentina. According to Jordan, Dyani lived apart from the other members of the band as he attempted to pave his independent path. That is not to say he drifted from the other members, as Jordan recalls that Dyani treated the Dudu Pakwana and Mongezi Feza as his brothers.[16]

Johnny left The Chris McGregor Sextet in 1968, and began taking on shorter partnerships with other musicians around London. During this time, he played alongside famous musicians Leo Smith, Evan Parker, Derek Bailey and John Stevens. He married a British woman named Pearl and moved in with her in the same house in which Evan Parker was staying. The marriage ended almost as soon as it begun and may have been a result of Dyani wrestling with his inner demons, or perhaps it was a marriage made in haste and destined to fail. Arguments have been made that although the substance abuse broke his body in later years, it also probably allowed him to open up his creative mind to reach his full potential.[17] What is clear is that Dyani was restless, as he failed to stay in one location for a period longer than two years and was married for a short period of time. He was extremely young when he arrived in Europe, and his soul undoubtedly yearned for his country and his source of inspiration.

Dyani followed Mongezi Feza to Sweden in 1969 where he met American jazz artist Don Cherry. Dyani played alongside Don Cherry between 1969 and the summer of 1971 and during this time he joined Okay Temiz, a Turkish percussionist, to form the trio named Eternal Ethnic Sound. In the winter of 1969 and early 1970, Johnny was an artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College in the United States, an Ivy League university boasting many brilliant minds.[18] This time as an artist-in residence allowed Dyani not only to reflect on his thoughts, but also to analyze jazz in the United States. He was unimpressed with what he found. Dyani was quoted saying “in Europe they admire the Americans so much but the Americans are copying us [South Africans] . It all comes from Africa but the South African musicians are not strong enough within themselves and don’t have enough belief within themselves. They let themselves be used”.[19] He also exclaimed how American artist Steve Lacy’s music was “nothing new”. It was around this time that Dyani began to vocalise his frustration with other exiled South African musicians, how he perceived them as “selling out” and the system all the exiles were trapped in.

Dyani was becoming increasingly frustrated with other South African musicians not taking the initiative and leading the way with their unique jazz music. He was also frustrated that they were not doing more to contribute towards the struggle against apartheid. At this point Dyani was a developed musician and had played on four different continents before turning twenty-three. By then he had transformed into not only a brilliant and diverse musician, but also bolstered an open mind and explicit opinions. He voiced these opinions during interviews and began using his talents in political efforts. Dyani was one of many artists who were in a period where jazz music was used as a form of protest.[20]

In 1972, Johnny moved to Denmark where Mongezi Feza and Dollar Brand were living. Dollar had recently converted to Islam, changed his name to Abdullah Ibrahim, and managed to convince Johnny to convert too. The conversion to Islam allowed many people, such as Abdullah Ibrahim, the motivation they needed to quit drugs and alcohol. Islam sees alcohol and drugs as abhorrent and foul calling them haram, and so converting to Islam involves abstaining from these substances and dissuading others from partaking in them. This was not the case for Johnny: he fought drug and alcohol abuse for many years after converting. Johnny possessed a religious mind and even carried an English translation of the Koran wherever he went thereafter.[21] Perhaps Johnny used alcohol and drugs as an escape from his frustration with what he considered sell-out South African musicians who instead of owning their music and leading the way, they instead worked for European counterparts. A contrasting perspective is that perhaps he simply longed to return home, or maybe even because he left home when he was so young and had no parental figure to guide him on a healthier path.

He also had a traumatic past as a black South African living under oppression and he learned the story surrounding his birth only as an adult after he had left South Africa. Whatever the reason, Johnny struggled with something inside of him which led to the substance abuse. Dyani lived with demons inside of himself, which caused him to behave violently as an attempt to rid himself of those demons. One particular incident was when he attacked his friend, Harvey Cropper, with a broken bottle.[22]

In 1973, Dyani toured Europe with Abdullah Ibrahim and his band named African Space Program. The partnership between the two allowed them to create a truly South African sound within their jazz music. Ibrahim was quoted saying “we were actually sort of consolidating our background experience, our history. And we found that it was valid … not our individual experience, but our national, African experience”.[23] Dyani and Ibrahim’s unique sound resonated with other South African artists in exile and in fact still reflects that true South African sound within jazz music. This is arguably his greatest contribution to music as he created South African art which is still appreciated today.

Political Involvement

Johnny’s single greatest hit is titled Song for Biko and was written after the news that Steve Biko, leader of the Miriam Makeba. Dyani was not a politician, but he realized his ability to contribute to the work of ANC by using his musical talent.[26] He remained frustrated with the ‘sell-outs’ in the exiled South African musician community, and perhaps he saw playing in Lagos as his means to contribute towards the struggle against apartheid instead of other exiled musicians performing only for monetary gain. Dyani was quoted saying:

‘I’m trying to work for Africa so that Africa can work for me…Where the other cats are concerned the instruments are playing them, instead of them playing the instruments. I mean, I refuse to be played by an instrument’.[27]

Dyani could not physically return to South Africa, but perhaps whilst in exile he could use his music and his presence at these sorts of events and festivals to bring global awareness to apartheid. Besides performing at FESTAC, Dyani assisted in organizing the 70th anniversary of the ANC and even contributed part of his royalties from his music sales to the ANC. According to Lindiwe Mabuza, who was the ANC Chief Representative to Scandinavia and based there from 1979-1988, Dyani was the cultural ambassador to the ANC and committed to making a difference.[28]

Unfortunately, even contributing to the struggle against apartheid through the medium of music could not calm Johnny’s spirits. In 1980, Johnny suffered a nervous breakdown and left Denmark for Sweden where he would remain until his death. It is important to note that like many other exiled musicians, Johnny was a traumatised human being as he was a man who had once lived under the oppression of apartheid and had fled leaving behind family, friends and the comforts of home no matter how slight they may have been. Not only that, but he also left home when he was sixteen and was flung into a new, strange world in Europe. Much of his life had consisted of rapid change and uncertainty, which would leave any reasonable person confused and fragile. This links back to his aggressive outbursts: Dyani was a traumatised man, and not a divo (male diva) who was acting out on a whim.

The 1980s were riddled with occasions of angry outbursts by Dyani. At a concert in Denmark, Dyani smashed his new Sony tape recorder which he received as a gift after a small altercation about money. He then proceeded to smash his own bass which he had carried with him since his days in South Africa.[29] These actions are indicators of a man who was deeply troubled, and not someone who could be soothed with the knowledge that he was putting forth his best effort in the struggle against apartheid when he saw no results.

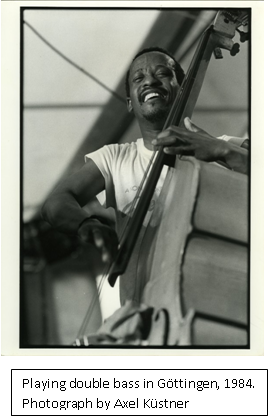

Playing double bass in Göttingen, 1984. Photograph by Axel Küstner.

Playing double bass in Göttingen, 1984. Photograph by Axel Küstner.

As Johnny grew older and his reputation as a brilliant musician flourished, he became increasingly politically involved. In 1982, he played at the Festival of Culture and Resistance in Gaborone, Botswana. It was around this time that he became distressed with news of South Africa on the verge of a civil war as violence broke out in many incidences during the 1980s. Johnny must have heard news of his family and friends being forcibly removed from their homes, along with the death of his brother, Nuse. What frustrated him even further was that he could not return home because he no longer held a South African passport and he was active within the exiled ANC, meaning the National Party would never allow him back into the country.[30] Dyani was so engaged politically during the 1980s that he was named the cultural ambassador of the ANC in Stockholm, which speaks in itself of his effort from exile in the struggle against apartheid.

By 1985 Johnny’s health began to deteriorate as a result of his substance abuse. He had since quit drugs and alcohol, but the damage was irrevocable. Whilst on tour in Berlin in 1986, Johnny collapsed backstage after performing in a concert and slipped into a coma. He died ten days later on 26 October. He was only thirty-nine years old.[31]

Johnny’s body was returned to East London, where local newspapers and Drum magazine covered his story in great detail. He was given a Christian funeral despite being Muslim.[32] As a tribute to his efforts within the ANC, the exiled party hosted a memorial concert in Sweden in his name where the likes of Abdullah Ibrahim and Dudu Pukwana performed.[33] The love and appreciation for Dyani that was showed in the weeks following his death is testament to his influence as musician in exile and his ability to touch the hearts of others through his music. Although he may have felt as if he were not reaching his full potential at times and remained frustrated with the situation in South Africa, his impact in the struggle did not go unnoticed by his professional peers and his family.

Johnny Dyani was an exceptional musician whose influence was only cut short by his untimely death. In collaboration with Abdullah Ibrahim, he created a truly South African sound in their jazz music which resonates the essence of his inspiration: his cultural heritage. He mixed the influence of kwela music and Xhosa sounds which stuck with him from his childhood playing on street corners, molded it with his learnings and experience playing with talented artists from all corners of the globe, and used it to create a unique sound. Johnny did not live to see the end of apartheid, but his music played a role in helping South Africa achieve its democratic freedom, no matter how small that contribution may have been.

End Notes

[1] Lars Rasmussen, Mbizo: A Book about Johnny Dyani (Copenhagen: The Booktrader), 9. ↵

[2] Ibid. ↵

[3] Ibid. ↵

[4] Ibid., 10. ↵

[5] Ibid. ↵

[6] Ibid., 12. ↵

[7] Pallo Jordan, Johnny Dyani: A Portrait” (Johannesburg: Rixaka), 4. ↵

[8] Ibid. ↵

[9] Ibid., 6. ↵

[10] Carol Muller, “Sounding a New African Diaspora: A South African Story,” Safundi (13:3-4): 282. ↵

[11] Ibid. ↵

[12] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 17. ↵

[13] Charles de Ledesma and Barry Kernfeld, Dyani, Johnny, (Grove Music Online). ↵

[14] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 18. ↵

[15] de Ledesma and Kernfield, Dyani, Johnny. ↵

[16] Pallo Jordan, Email Interview. ↵

[17] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 18. ↵

[18] Ibid. ↵

[19] Ibid., 85. ↵

[20] Sam Washington, “Exiles/Inxiles: Differing Axes of South African Jazz During Late Aapartheid,” (South African Music Studies). ↵

[21] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 20. ↵

[22] Ibid., 22. ↵

[23] Muller, Sounding a New African Diaspora, 288. ↵

[24] Richard Williams, “Rock/Jazz,” The Times, (London). ↵

[25] Jordan, Email Interview. ↵

[26] Rasmussen, 21. ↵

[27] Eric Akrofi, Maria Smit and Stig-Magnus Thorsén, Music and Identity: Transformation and Negotiation, (Stellenbosch: Sun Press), 261. ↵

[28] Ibid, 265-266. ↵

[29] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 22. ↵

[30] Ibid., 24. ↵

[31] Tom Cheyney, Johnny Dyani Dies, The Beat, (Los Angeles). ↵

[32] Rasmussen, Mbizo, 27. ↵

[33] African National Congress, Minnekonsert for Johnny Dyani, 1987. ↵

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project