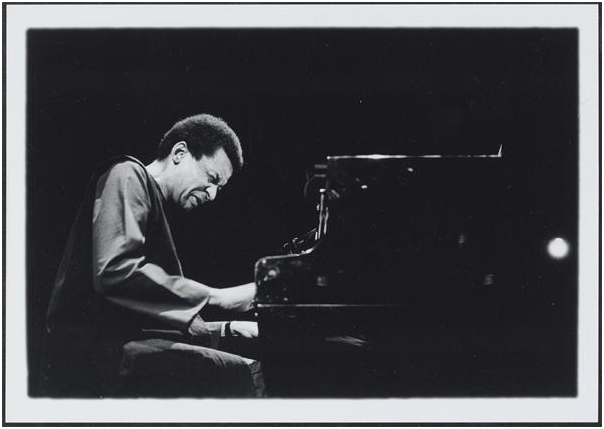

Figure 1 Image source

Figure 1 Image source

Abdullah Ibrahim is a profoundly influential South African jazz musician who was frequently oppressed by the apartheid regime in South Africa. As a Coloured man in South Africa, Ibrahim was greatly restricted by segregation. He eventually sought political exile in Europe and the United States.[1] During his time in exile, Ibrahim found success and developed his musical capabilities. In this way Ibrahim was able to use his musical ability and commercial success to become a voice for the oppressed people in South Africa. Through his experiences in exile and the influence of his music, Abdullah Ibrahim underwent a spiritual and cultural evolution through which he became a voice for oppressed people to help break the oppression of apartheid and aid in the reconstruction of South African culture.

Abdullah Ibrahim was born in 1934 in Cape Town, South Africa. His father was Sotho and his mother of mixed racial ancestry. Within the context of racial constructions in South Africa he was classified as a Coloured person, which was the largest community in Cape Town at that time.[2] Ibrahim’s birth name was Adolph Johannes Brand, a name he would later change to Abdullah Ibrahim to fit his new cultural identity. From a young age Ibrahim expressed an interest in music and was exposed to a variety of musical styles and influences, including African music at home and Christian spiritual music in church. Ibrahim began playing the piano at age seven. He would later apply to the University of Cape Town’s College of Music, but was refused due to his racial ancestry. Though this was a major obstacle, this did not halt his musical pursuits. Ibrahim continued to study jazz music and obtained jazz records from Americans at the Cape Town docks. This led to his friends giving him the nickname Dollar, a name he would come to accept and use professionally.[3] In 1958 he formed his own jazz band known as the Dollar Brand Trio. He would go on to perform with other well-known African artists such as Hugh Masekela and Kippie Moeketsi. In 1965 Ibrahim married Sathima Bea Benjamin, whom he met and performed with throughout the late 1950’s. In 1968 after many years in exile, Ibrahim began seeking spiritual enlightenment. He converted to Islam and changed his name from Dollar Brand to Abdullah Ibrahim. He would later make a pilgrimage to Mecca. Ibrahim has two children, Tsidi and Tsakwe. He now lives in Cape Town, South Africa and performs with the Cape Town Jazz Orchestra.1

Ibrahim grew up in a poor area of South Africa and frequently was involved with the area known as District Six. District Six was a hub for Black culture in South Africa. However, during 1968 many of the inhabitants of District Six were forcibly removed by the apartheid government because of the colour of their skin. This removal only furthered the oppression of Black and Coloured culture. Despite this oppression, many Black and Coloured individuals continued to maintain their own cultural identities. When Abdullah Ibrahim was asked in an interview about this removal and if it had wiped out much of Black and Coloured culture as the government had intended he replied, “That can never be wiped out! It’s a people’s dream, and dreams can never be wiped out.” He goes on to say that “We musicians are the historians. We record our experiences and our history within our music. Some of the pieces we play are very old, in fact ancient traditional songs from the whole area.”[4]

Ibrahim’s music career really began to gain momentum in an area near Johannesburg known as Sophiatown. It was here that he formed the Jazz Epistles with several other South African jazz musicians. The Jazz Epistles quickly became one of the most influential jazz bands in South Africa. Ibrahim was more concerned with his music being a form of personal expression rather than a source of financial success. Ibrahim and many other members of the Jazz Epistles had personal experience with the oppression that apartheid breeds, which they actively fought against using their musical compositions. Historian John Edwin Mason remarks that the Jazz Epistles “were engaged in a kind of cultural guerilla warfare against the laws, values, and expectations of the apartheid state.”2 Mason states that the police “progressively shut down racially integrated nightclubs and enforced statutes which prohibited both Black musicians from playing before White audiences and musicians of different races from performing together.”2 In an interview, Ibrahim recalls the oppression he and his fellow musicians faced when he recounts that “the apartheid regime was ruthless in controlling our daily movement. You'd need permits to travel anywhere and you always faced imminent arrest. We sneaked out of safe houses to jam with other musicians. We also organized our own community concerts. Then the White-owned recording companies would rip off naive and uninformed musicians and record their music without acknowledgment or compensation.”[5]

This led to a mass exodus of many influential Jazz musicians such as Ibrahim. Ibrahim travelled to Europe in 1962. In Europe he began to perform and became a major success.6 Ibrahim soon travelled to the United States where the Black power and civil rights movements were gaining traction. With jazz becoming increasingly important to South Africans, Ibrahim’s worldwide success allowed him to use his influence to combat censorship and oppression in South Africa. This was an important point to Ibrahim as he observed that “there has probably never been a revolution that did not use songs to give voice to its aspirations, or to unite and strengthen the morale of its adherents.”[6] For many people, jazz became a symbol of resistance. The oppression of jazz musicians was very similar to how the apartheid government oppressed Nelson Mandela and other prominent members of the African National Congress. This is especially evident with how the government censored people’s speech through the Suppression of Communism Act and how many artists were forced into exile to continue creating their cultural works.

Discrimination and the laws enforcing policies of segregation were major obstacles for Abdullah Ibrahim in South Africa during apartheid. The Group Areas Act restricted movement significantly between cultural groups. This led to many Black, Coloured, and Indian citizens being limited as the apartheid government claimed that they wanted these races to develop along their own lines. In 1979, Ibrahim claimed that it was almost impossible to be a successful musician if you were not White in South Africa.6 This was due to the fact that musicians needed special permits to perform for audiences of other races. Many Black, Coloured, and Indian musicians in South Africa had to resort to taking on other jobs just to survive. During Apartheid, Sophiatown became a cultural hub and this was where Ibrahim formed a jazz band known as the Jazz Epistles with other well-known South African jazz musicians such as Kippie Moeketsi and Hugh Masekela. Because jazz was an expressive art form, many famous South African jazz musicians were using it as a means to seek social equality between races. This presented many obstacles to the apartheid government and their doctrine of segregation. The South African government began taking measures to limit the influence of jazz music such as banning jazz from radio broadcasts and segregating performances. This excessive repression forced Ibrahim to seek exile and perform across Europe and the United States.[7]

In an interview Ibrahim described a feeling of liberation when he first travelled to Europe. He stated that he “joined the wave of people, young and old, leaving the country in 1962. European audiences and musicians were very receptive to what I was playing. Some were hostile, especially when I became identified as an avant-garde musician. But it was the feeling of total creative liberation. It was a wonderful feeling to finally present music written in South Africa, without worrying about restrictions, the market, and political and social pressures.”6 While this new sense of freedom allowed him to develop the style he had used previously in South Africa, exposure to new musicians and musical styles allowed him to adapt his approach to music in a way that allowed him to grow as an artist.

Ibrahim briefly returned to South Africa in the early 1973 and began composing music there. One composition by Ibrahim that is particularly well known from this time is Mannenberg. Mannenberg is a jazz piece that Ibrahim composed during some of the most pivotal moments of the South African struggle to end apartheid. Mannenberg immediately became a major success in South Africa and around the world. Mannenberg incorporated many folk elements from African culture and was seen as a musically and politically progressive composition. Because of these aspects, Mannenberg was adopted as an unofficial anthem of the struggle for freedom in South Africa. Mason states that many people and groups “politicized the song by playing it at the innumerable rallies and concerts, linking it directly to the anti-apartheid politics of the United Democratic Front [UDF] and other progressive organizations.”2

Ibrahim’s musical style was an impressive combination of other musical influences such as western European and American musical ideas combined with the African traditions he was exposed to when he was growing up in South Africa. He used this broad knowledge to express his personal beliefs and make complex statements using his music. Lewis Nkosi, a prominent South African writer sent into exile, comments that Ibrahim “builds up a series of intensely personal statements, one becomes struck by his pianistic skill and the breadth and scope of his music. Rarely are a musician’s emotions so strongly reflected in his music.”[8] This combination allowed Ibrahim to appeal to a variety of people. Abdullah Ibrahim has stated believes that jazz as a genre is inherently Africa-based and that there is a strong connection between contemporary African music and jazz. This is in opposition to the popular belief at the time that jazz is a western construct and many musicians sought to imitate the American and European styles of jazz. In 1968, Ibrahim said that he wanted people to “understand that everything needed to create and sustain a vital musical culture existed in South Africa.”2 Ibrahim also has said that he thinks of music as a spiritual experience. According to Ibrahim music is more than just playing certain notes, he claims that in traditional African societies the musically inclined individuals would often become the religious priests or healers. When asked about the role of a musician he claimed that “musicians are miscast as entertainers when their role is more akin to that of healers.”[9] While this view is not common in western society Ibrahim believes that people in western culture also view music in this way, but that they just do not realize it.4 Because of this, Ibrahim believes that the struggles portrayed through jazz could be shared by both people in the United States and in South Africa. Many critics and observers shared this view. Wilfrid Mellers claimed that Ibrahim’s musical style breaks down “barriers between classical, jazz and pop—as well as of races.”[10]

In the late 1960’s, Ibrahim was faced with increasingly difficult struggles. He often described how he felt like he was struggling to find a place. His health was declining rapidly and he was losing sight of his lifelong goals. This sense of personal crisis lead him to the decision to return to Cape Town in 1968. While in Cape Town, Ibrahim decided to embark on a physical and mental cleansing of his destructive behaviors. This led him to give up heavy drinking and discover spiritual enlightenment through Islam. In 1970, Ibrahim left Cape Town to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. For Ibrahim, Islam evoked a spiritual side within him.1 He felt as though he had found his liberation. His lifestyle changes, both physical and spiritual gave him the sense that he had become a new person. For this reason he changed his name from Dollar Brand to Abdullah Ibrahim. Filled with new spiritual insight and a sense of renewal, he channeled this energy into his music and as such much of the music he created during the following decades dealt with themes of liberation and homecoming.

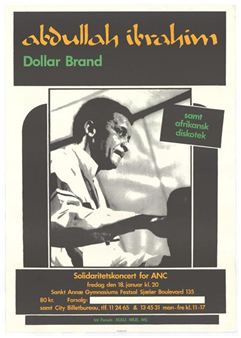

Ibrahim was always an active individual in the struggle against apartheid. For him, the fight for freedom was not only political, but also personal. As a Coloured person in South Africa he was often looked down upon by Whites. During the period of apartheid many Whites associated Coloured people with immorality and often suspected him of being a criminal. These views were set forth by antiquated ideas about race and racial science. Because these views were so ingrained in South African culture that many people accepted them as facts and Ibrahim was constantly faced with discrimination and hate. He saw firsthand what apartheid does for tearing individuals apart instead of bringing them together. This prompted him to do whatever he could to help those active in the political struggle to end apartheid in South Africa. One such instance was when he staged an illegal benefit concert for the African National Congress in 1976.1 In the early 1990’s when the apartheid government began making many changes to its policies to allow greater freedoms for Black, Coloured, and Indian South Africans, Ibrahim commented that “the recent changes in South Africa are of course very welcome, it has been so long in coming. We would like a total dismantling of apartheid and the adoption of a democratic non-racist society; it seems to be on the way.”[11].

Figure 2 A promotional poster for Ibrahim’s ANC benefit concert Image source

Figure 2 A promotional poster for Ibrahim’s ANC benefit concert Image source

Abdullah Ibrahim is an immensely influential figure and he is noted as one of the brave artists who used their talent and ability to help others stand up to the apartheid regime. Born into a country that oppressed him and his community because of racial ideology, he sought to use his musical talent to inspire others to resist the apartheid regime. Despite numerous attempts to restrict him, Ibrahim was able to break through the oppression presented by apartheid and aid in the reconstruction of South African culture. While in exile he found himself shaped through his experiences and the influence of other musicians. From his time in exile Abdullah Ibrahim underwent a massive spiritual and cultural evolution through which he became a voice for oppressed people to help break the oppression of apartheid and aid in the reconstruction of South African culture.

Bibliography

Abdullah Ibrahim: Dollar Brand. [ONLINE] Available at: www.aluka.org. [Accessed 20 November 2016].

"Abdullah Ibrahim." South African Music. Accessed November 20, 2016. www.music.org.za/.

(2016). Abdullah Ibrahim | Biography. [ONLINE] Available at: abdullahibrahim.co.za/. [Accessed 20 November 2016].

Boersma, P., (1987), Part 01, Anti-Apartheid activities in the Netherlands: Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand), Amsterdam, December 1987. [ONLINE]. Available at: www.aluka.org [Accessed 25 October 2016].

Ibrahim, A., 2016. An Interview with Abdullah Ibrahim (1995) | Crownpropeller's Blog. [ONLINE] Available at: crownpropeller.wordpress.com/. [Accessed 21 November 2016].

Ibrahim, A., (2011). Interview: Abdullah Ibrahim - JazzWax. [ONLINE] Available at: www.jazzwax.com/. [Accessed 28 October 2016].

Mason, J., "'Mannenberg': Notes on the Making of an Icon and Anthem." African Studies Quarterly, 9(4), 2007. General OneFile, go.galegroup.com. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Mellers, W., (1966). “Reviewed Work: Anatomy of a South African Village and Other Items by Dollar Brand.” The Musical Times, [ONLINE] Available at: www.jstor.org.

Muller, C., (2001). “Capturing the "Spirit of Africa" in the Jazz Singing of South African-Born Sathima Bea Benjamin.” Research in African Literatures, 32(2), pp. 133-152 [ONLINE] Available at: www.jstor.org. [Accessed 28 October 2016].

Nkosi, L., (1966). Jazz in Exile. [ONLINE] Available at: www.jstor.org. [Accessed 28 October 2016].

South African History Online. (2016). Abdullah Ibrahim and the Politics of Jazz in South Africa. [ONLINE] Available at: www.sahistory.org.za/. [Accessed 27 October 2016].

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. 2016. Abdullah Ibrahim - Wits University. [ONLINE] Available at: www.wits.ac.za/ [Accessed 21 November 2016].

End Notes

[1] "Abdullah Ibrahim | Biography." Abdullah Ibrahim. Accessed October 19, 2016. abdullahibrahim.co.za ↵

[2] Mason, John Edwin. "'Mannenberg': notes on the making of an icon and anthem [1]." African Studies Quarterly, vol. 9, no. 4, 2007. go.galegroup.com/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016. ↵

[3] The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. (2016). Abdullah Ibrahim - Wits University. [ONLINE] Available at: www.wits.ac.za. [Accessed 27 October 2016]. ↵

[4] Ibrahim, Abdullah. "An Interview with Abdullah Ibrahim (1995)." Crownpropeller's Blog. 2012. Accessed November 18, 2016. crownpropeller.wordpress.com. ↵

[5] Ibrahim, Abdullah. "Interview: Abdullah Ibrahim." JazzWax. April 11, 2011. Accessed November 19, 2016. www.jazzwax.com/. ↵

[6] Vershbow, Michela E. "The Sounds of Resistance: The Role of Music in South Africa's Anti-Apartheid Movement." Inquiries Journal. 2010. Accessed November 19, 2016. www.inquiriesjournal.com/ ↵

[7] Muller, Carol, 2016. Capturing the "Spirit of Africa" in the Jazz Singing of South African-Born Sathima Bea Benjamin. [ONLINE] Available at: www.jstor.org. [Accessed 28 October 2016]. ↵

[8] Nkosi, Lewis. "Jazz in Exile." Transition, no. 24 (1966): 34-37. www.jstor.org/. ↵

[9] Jaggi, Maya. "The Guardian Profile: Abdullah Ibrahim." The Guardian. December 07, 2001. Accessed November 18, 2016. www.theguardian.com/. ↵

[10] Mellers, Wilfrid. “Reviewed Work: Anatomy of a South African Village and Other Items by Dollar Brand.” The Musical Times 107, no. 1479 (1966): 419. www.jstor.org/. ↵

[11] "Abdullah Ibrahim." South African Music. Accessed November 20, 2016. www.music.org.za/. ↵

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project