Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

The yearly Human Rights Day public holiday in South Africa in late March commemorates the Sharpeville Massacre, when police opened fire on a crowd of unarmed black protesters outside the Sharpeville police station on 21 March 1960. An estimated 69 people were killed and 180 injured, many shot in the back as they fled the scene.

The protest, led by the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, was against the hated identification document, known as a “dompas” (dumb pass), that the apartheid regime forced black people to carry, and which controlled their movements.

After the first democratic elections of 1994, President Mandela proclaimed 21 March a public holiday as a way of remembering the egregious human rights abuses of apartheid symbolised by the 1960 massacre.

He made another significant symbolic gesture: he selected Sharpeville, about 70km to the south of Johannesburg, as the site where he signed the country’s constitution into law on 10 December 1996.

Unfortunately, human rights abuses continue in democratic South Africa 27 years after the end of apartheid. Echoes of Sharpeville remain evident, particularly in the way in which police behave towards South Africans.

In this article, we draw on survey data to profile awareness of the Sharpeville massacre, and views on the general importance of remembering a painful past.

We believe this is important because the way people understand the past is likely to have a clear bearing on levels of support for a social compact, and associated policies to address the challenges facing the country. At the top of the list are poverty, inequality and unemployment.

Who remembers what

To explore the patterns of collective memory in the country, the Human Sciences Research Council designed questions for inclusion in its annual round of the South African Social Attitudes Survey. The survey, conducted between March 2020 and February 2021, consisted of 2,844 respondents older than 15.

The results suggest that basic public awareness of key historical events in the country is low. Nevertheless, those who were surveyed recognised the importance of remembering the past.

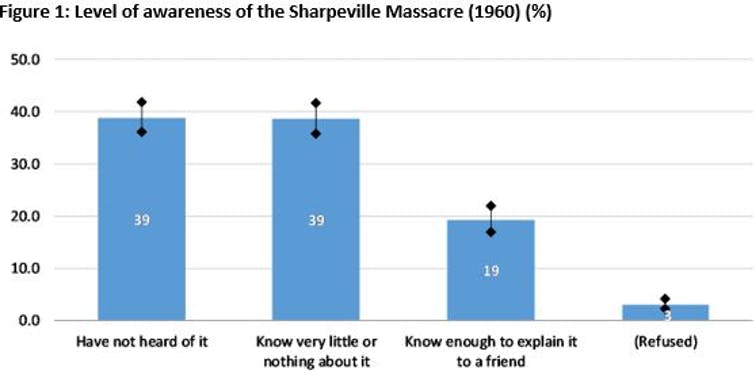

The survey asked respondents: “How familiar are you with the following historical events? Sharpeville Massacre 1960”. Two-fifths (39%) had not heard of this event before (Figure 1). A further 58% said they had heard of it, of which 39% knew little or nothing about it. A mere 19% knew enough about it to describe it to a friend.

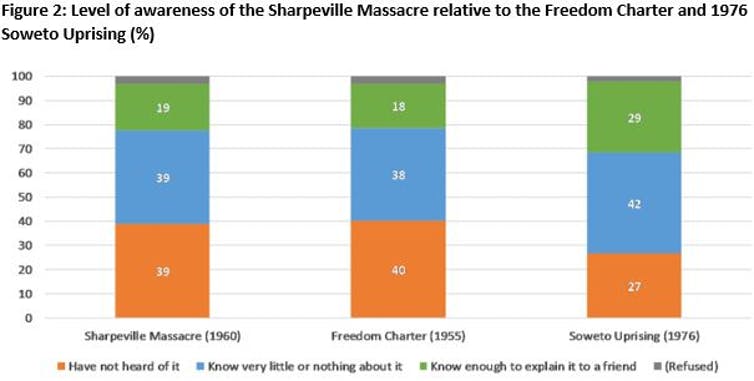

Many will be shocked by the limited public knowledge of a key event in modern South African history. To gain some perspective, we compared findings on knowledge of the Sharpeville massacre to knowledge of both the 1955 Freedom Charter and the 1976 Soweto Uprising.

The Freedom Charter is the statement of core principles that guided the African National Congress and allied organisations in the fight against apartheid, after it was adopted on 26 June 1955 at the “Congress of the People” in Kliptown, Johannesburg. The 1976 Soweto Uprising was sparked by the introduction of Afrikaans as the language of instruction for some subjects for African high school students in that year. The marching students were met by armed policemen, who opened fired on them, killing several. This prompted countrywide resistance for several months thereafter.

In the survey, awareness of the Freedom Charter was similar to that of the Sharpeville massacre, with 57% having heard of it and 40% not. Basic familiarity with the 1976 Soweto youth uprising was higher at 71%, with 27% reporting no knowledge of it.

In all three instances, the share of respondents who were confident they would be able to describe these historical events to someone else ranged only between 18% and 29%.

These findings suggest that levels of knowledge about specific events remain quite shallow.

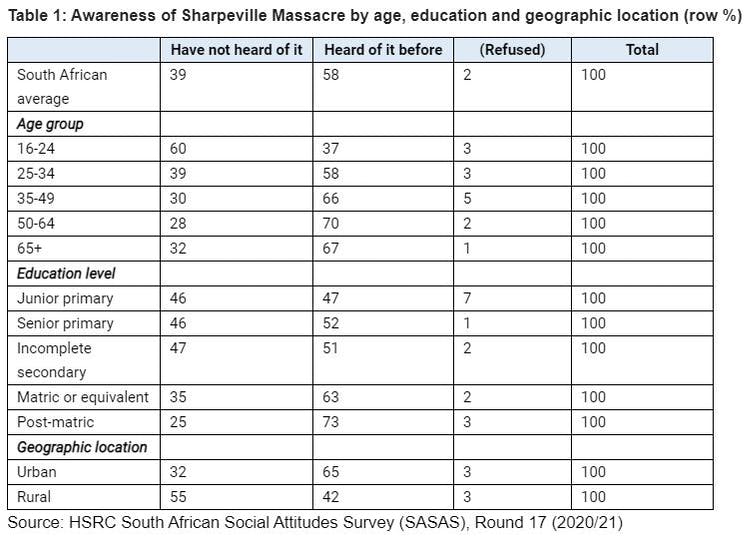

Another striking finding was the wide variation in awareness levels. A strong generational difference in awareness of the Sharpeville massacre is evident, with 60% of those aged 16-24 never having heard of this important event.

There was also a strong class gradient. For example, poor and rural adults displayed lower levels of awareness.

The influence of education was especially pronounced in shaping awareness. The more educated an individual, the more likely they were to be aware of the Sharpeville massacre.

Why it matters

When asked “in your view, how important or unimportant do you think historical events such as the Sharpeville Massacre and Freedom Charter are for people living in South Africa today?”, 74% answered that this was “very” or “somewhat” important. Only 14% said that remembering the past was “not very” or “not at all” important, while 12% were uncertain.

This view is common among large numbers of the public, irrespective of personal socio-economic and demographic characteristics. Across a range of variables, the share of respondents believing in the importance of historical events does not fall below 60%, and ranges up to around the 85% mark.

Those with more knowledge of events such as the Sharpeville massacre showed a keener sense of the importance of collective memory than those who lacked awareness.

The manner in which Germany has approached its traumatic Nazi history offers a good illustration of how a society can reckon with its past. The country is recognised as having developed an acute historical sensitivity, preserving an understanding of the past through sustained effort to educate and inform.

Lest we forget

The low levels of familiarity with key historical events indicate that there are serious shortcomings in the development of national collective memory in South Africa.

A national collective memory is crucial for the achievement of a national identity, since identities are closely linked to the common memories, including values, that a group holds. In the case of South Africa, a collective national identity would go a long way in building the social compact required to address the many challenges that the country faces.

South Africa could perhaps look to Guatemala. An attempt was made to use education to promote national unity in Guatemala when a peace accord was signed in 1996 at the end of violent conflict in that country. The country shifted towards human rights education in an effort to emphasise the diversity of its population and a culture of peace.

A key focus was the rights of children, women and indigenous populations. Unlike South Africa, Guatemala failed to include the history of the conflict in its national history curriculum. But, like South Africa, there was a failure to develop a collective memory based on a history that emphasises historical events that can foster national unity.

Our survey results show that more needs to be done to ensure the public is well-informed of key events in South African history, and the relevance they have for contemporary issues.

In part, this must include a review of the place of history in school and university curricula, and recognition of the need for further investment in civic and democracy education. Countries such as the United States are investing in civics education and learning as a way of addressing hard histories and mounting challenges to democracy. Perhaps it is time to place this more firmly on the South African agenda.