Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

In 1996 Michael Scurr penned the following article on the restoration of the Old Cape Archives (today the Centre for the Book). It was published in Restorica, the journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation. Thank you to the University of Pretoria and the Heritage Association of South Africa for giving us permission to publish.

The Old Cape Archives, a National Monument and most prominent architectural landmark in Queen Victoria Street, Cape Town, has now been fully refurbished and restored as the culmination of a two-phase programme commissioned by the Department of Public Works.

The restoration is part of a long-term programme initiated by the PWD during which attention has been deliberately focussed on preserving and revitalising culturally significant buildings throughout South Africa. The completed restoration of the contemporary Union Buildings and the restoration of the Palace of Justice on Church Square, Pretoria, are examples, particularly with regard to similar fine stonework of period detailing. As in the case of the Old Archives, these buildings have also benefited from the guidance of senior PWD architects Cliff Green and Peet Wolmarans.

Architects for the restoration were Rennie and Goddard of Cape Town, who have been involved in such award winning restorations as the East London City Hall, the historic Vergelegen homestead near Somerset West and the National Monuments Council offices in Cape Town.

Following the moving of the Archives to the former Roeland Street gaol site in recent years, the State-owned "Old Cape Archives" has been occupied by the South African Library. This sandstone building, secluded garden and adjoining privately owned stackroom block are now to be fully used for library purposes and will be a welcome and elegant extension to the library headquarters further down Queen Victoria Street. The intention is also to make full use of the grand central domed hall and fine meeting rooms for special exhibition purposes, public lectures and chamber music.

The recently completed Phase 2 restoration follows on the first phase roof-top contract during which the copper dome, green-glazed tiled towers, pitched roofs and the ornate end pavilions complete with fishscale tiles and coronets were all extensively restored. This work was carried out by Gordon Verhoef & Krause during 1992/1993. The Phase 2 contract, awarded to Wilson Bayly Holmes-Ovcon, involved the complete refurbishment of the interior, the insertion of modern services and further and more extensive replacement of and repair to external stonework.

Old Cape Archives (M Van Bart)

Old Cape Archives (M Van Bart)

Background

The Old Cape Archives was built in two stages between 1906 and 1913 to serve as the Senate House and administrative offices of the University of the Cape of Good Hope. This examining institution had very close ties at the time with the South African Library and with what is today the University of Cape Town and formed the nucleus of the present Pretoria-based University of South Africa.

The 1906 grand design was won in competition by Messrs Hawke and McKinlay Architects of London. They came to the Cape to carry out the commission and were subsequently also responsible for the stately grey granite Supreme Court further down Queen Victoria Street, as well as for the Johannesburg City Hall and, in association with Percy Walgate, for the nucleus of the UCT Rondebosch Campus. The fine interior marble paving, crisp plaster vaulted and moulded ceilings and the elegant teak and oak joinery - well appointed with brassware found in these buildings epitomise the contribution of this firm to the Arts and Crafts detailing of this era in South Africa.

Old postcard (uploaded onto flickr by HiltonT)

Old postcard (uploaded onto flickr by HiltonT)

Exterior

A main component of the restoration was the repair and replacement of external stonework. Much original sandstone was decayed and repair-disfigured and critical location at eye level mitigated against further extensive "plastic" repair on the facades.

Characterful curly-grained Flatpan Free State sandstone is no longer available as mining activities and slime dams have obliterated the quarries. A radical decision was therefore taken at the outset to replace the most severely scarred courses up to the piano nobile level with available and durable Cape granite, as an extension of the existing granite plinth.

Various stone repair techniques were employed overall. Aside from granite insertion, removed original Flatpan sandstone was utilised afresh for the replacement of specific and highly visible smaller sandstone elements such as balusters and modillions. Special plaster repair of less visible moulded sandstone was pursued with due reference to masonry layout and appearance.

The procedure involves careful cutting back at decayed areas and reinforced bonding with suitably placed copper wires. Repetitive elements including balusters and copings were precast while selected sheltered smaller mouldings and isolated minor damage were reinstated in blended sands and resin. General areas of the sandstone were cleaned by bristle brush scrubbing and the most severely stained, slurry-coated or chemically discoloured areas were manually scraped before extensive lime mortar repainting.

Interior

The alterations to the interior involved the removal of the antiquated lift and stairway insertion of the 1920s and the introduction of new service rooms and an appropriately sized 3-way-opening lift serving all eight levels for practical advantage.

The courtyards flanking the centre drum were roofed over with patent glazed rooflights at eaves level in order to improve climatic control and facilitate maintenance. New courtyard floors were also inserted close to corridor level to improve the usability of both lower ground and piano nobile floors. The columns along the curved marble and slate corridors were cleaned down and found to be of pink sandstone obscured by many layers of paint.

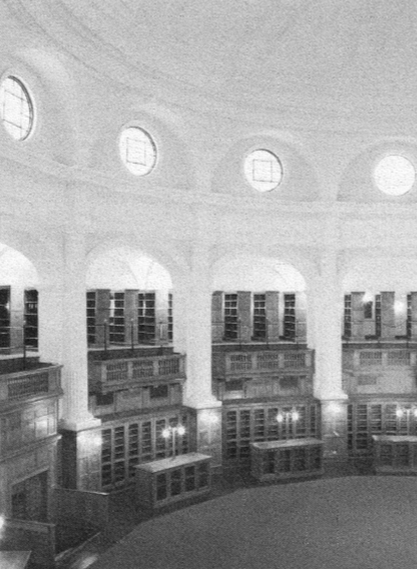

The central hall, which until recently housed the reading room of the Archives, was stripped of all added partitioning and shelving and twotoned afresh to highlight the architectural plasterwork to advantage. The ornate centre cupola lantern stands within a circular heavy glass pavement rooflight designed to send shafts of light down into the main hall. Old waterproofing was removed, the cast iron frames were reglazed and all was resealed to reinstate this period feature.

Centre lantern (Rennie and Goddard)

Centre lantern (Rennie and Goddard)

The hall has been planned to house several historic book collections with new glass-fronted perimeter and free-standing cases introduced to match the existing oak panelling. Additional units were made for the reconfigured layout on the gallery level to improve storage capacity with minimal intrusion.

The hall (Rennie and Goddard)

The hall (Rennie and Goddard)

Offices and reception rooms required general refurbishment, upgrading of services, general redecoration and provision of new, or restored original, light fittings.

A new teak reception cubicle was designed to control access and also to act as a central monitoring point for services. The foyer cloakrooms were replanned with references to woodwork and polished granite in the spirit of the original and numerous touches to fireplaces, original delicate bronze commemorative reliefs, ironmongery and so on, completed a long list of architectural tasks.

New requirements

The lower ground floor spaces, as well as the upper floors, house stackrooms, laboratories, workshops and general store rooms. Here, the main emphasis was on the provision of secure, climatically controlled and fire protected areas suitable for the library.

A simple covered walkway now facilitates all weather traffic between the main building and the nearby Slotsboo stackrooms. The redundant planthouse was demolished and replaced with a new building to cater for the present requirements.

The complex has a fire detection system installed throughout and CO2 protection is provided in the most important storage areas. The lower ground floor stackroms and main hall are air-conditioned partially using the original airways as planned by Hawke and McKinlay.