Archive category

Name of publication

Publication date

Published date

Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

“We were all kind of rebels,” drummer Louis Tebogo Moholo-Moholo recalls, “so, like birds of a feather, [we] flocked together.”

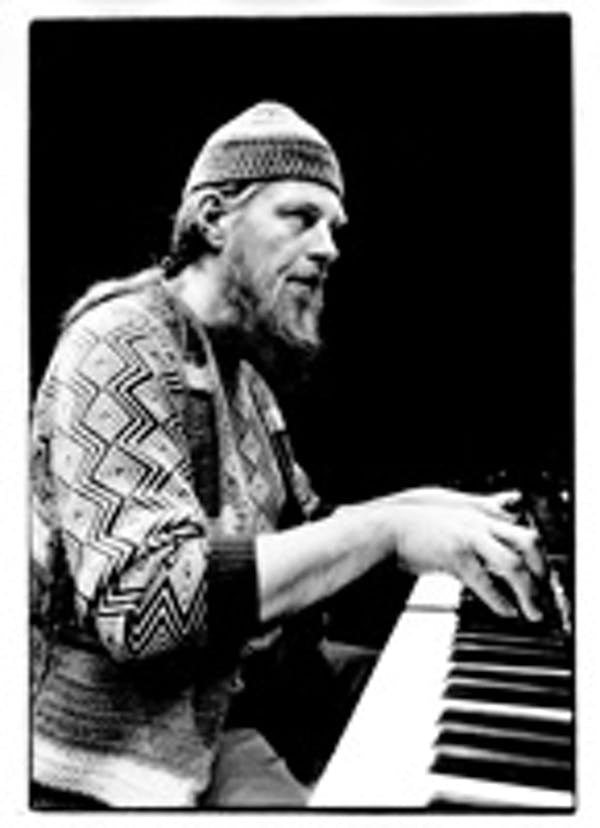

He’s talking about the Blue Notes, a multiracial modern jazz outfit formed in Cape Town in the early 1960s. White composer and pianist Chris McGregor joined forces with some of the most radical young black players on the city’s scene: alto saxophonist Dudu Pukwana, tenor saxophonist Nikele Moyake, trumpeter Mongezi Feza, bassist Johnny Mbizo Dyani and Moholo-Moholo, the only original Blue Note still alive and working.

Apartheid restrictions and the defiant, joyful freedom of the group’s music meant gigs were scarce, and the human tensions of operating in such a climate were corrosive. The Blue Notes left South Africa in 1964 for an engagement at the Antibes Jazz Festival in France. Moyake was forced home by ill-health shortly afterwards; the others stayed.

Moholo-Moholo returned home in 2005. Despite international acclaim, he found performance space for his adventurous concepts in South Africa as scarce as it had ever been. Meanwhile, the recordings and achievements of the Blue Notes remained obscure in South Africa, while they are legendary in the European jazz community.

Music is gold

That’s changing. On September 22, trumpeter Marcus Wyatt launches the debut recording of his Blue Notes Tribute Orkestra in Johannesburg. In a recent interview with me Wyattt declares the work of McGregor, Dyani, Pukwana and the rest as “gold”,

Not many people knew about it, but it’s music people should know.

His project is just one flower of a slow growing interest in recovering the legacy that seems finally to be breaking into bloom.

In Europe, the Blue Notes startled staid jazz scenes. Photographer Valerie Wilmer said they,

literally upturned the London jazz scene, helping to create an exciting climate in which other young players could develop their own ideas about musical freedom.

Pianist Keith Tippett was one of those. He recalls performances at Ronnie Scott’s 100 Club in London:

We played with everybody, but the Blue Notes – sometimes more than other British musicians – enfolded us and encouraged us… there was an inherent freedom and flexibility in the playing, coupled with impressive technique and a robust muscularity I’d never heard live before.

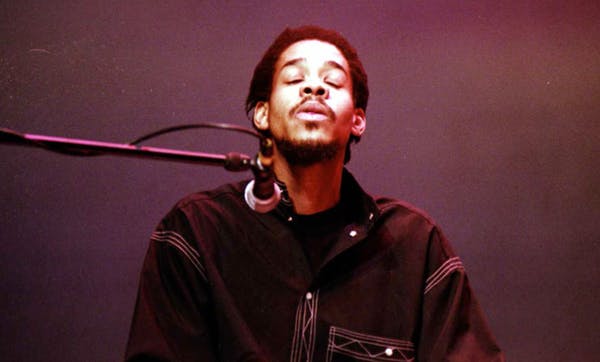

Wilmer likened what landed in London to the sound of a “Soweto shebeen” – but that geography is out by a thousand kilometres. Ideas from the Xhosa music – complex rhythms; overtone singing; the oscillating harmonics of stretched bowstrings; a heterophony of voices, each cycling through its own sequence of notes and beats – have infused Eastern Cape jazz. From the work of pioneering bandleaders such as Christopher Columbus Ngcukana in the 1950s right through to current players such as AndileYenana and FeyaFaku.

What is still the sound of family ceremonies, even in the cities, fostered ways of hearing music – not as one straight line, but rather as a collection of braided paths – relevant and useful for young musicians exploring the relationship between freedom and collectivity in jazz.

Post-liberation generation

By the mid-1990s, post-liberation, a younger generation of South African jazz players were travelling, and hearing about the Blue Notes from musicians abroad. The late pianist Moses Molelekwa reflected in an interview I did with him in 1995:

I’ve learned how you can just put musicians together in a room and make music that’s good enough to record: free improvisation. People tell me Chris McGregor worked like this, but although he was a South African, I can’t find his recordings here.

Saxophonist ZimNgqawana (who died in 2011) called his own improvisation “second generation South African free jazz” in , in acknowledgement of the first generation, which he’d learned about from Moholo-Moholo during a tour to Norway in 1996.

That’s how it was for Wyatt too, initially introduced to the Blue Notes opus by South African-born reedman Sean Bergin in Amsterdam,

though I’d heard older musicians here talking, especially about Mongezi and Dudu.

He describes the new album as,

a heritage project: a tribute, not appropriation or a set of covers, but applying fresh voices and ideas to amazing material.

Wyatt’s interest deepened when he was commissioned by Chimurenga’s Ntone Edjabe to arrange Blue Notes music for a 2011 Johannesburg concert themed around exile and xenophobia.

As Moholo-Moholo famously phrased it:

Exile is a fucker.

History of exploitation

There’s sensitivity in South Africa about appropriation; understandable in the context of a history of highly exploitative music industry relationships. In the course of untangling publishing rights for the material, Wyatt has consulted McGregor’s widow, son and brother, and Moholo-Moholo, among others. He supports concerns about proper attribution:

That’s important. You can – and should – claim royalties. But you can’t claim music. Music is shared love, and when it spreads, it’s one of the more positive viruses around.

Untangling rights wasn’t the only challenge Wyatt faced. He says transcribing the music was also demanding,

because of the denseness of the sound; the energy on the stage just taking it higher and higher.

Wyatt’s project was recorded at the Birds Eye Club in Switzerland, with a Swiss/South African ensemble comprising vocalist/trombonist Siya Makuzeni, pianist Afrika Mkhize, reedmen Donat Fisch and Domenic Landolf, bassist Fabian Gisler and drummer Ayanda Sikade.

The personnel won’t stay constant in live performances. Wyatt envisages the kind of moveable feast McGregor later presided over in his later big band, the Brotherhood of Breath, showcasing the highly individual strengths of different soloists. But that individuality was always grounded in the shared musical understanding the Blue Notes hammered out in their work together:

They really were a band and you can hear it. Sometimes groups here forget that and offer ‘free’ music without that bedrock.

Wyatt’s album is not the only project in the pipeline descended from South Africa’s first generation of free jazz. Pianist NduduzoMakhathini has recently spoken of a growing interest in the music of the Blue Notes. And Moholo-Moholo himself has finally found the right collaborators with whom to record in South Africa: in late October he will preside over the launch of the “Born to Be Black” album with the African Freedom Ensemble, formed by new-generation trumpeter Mandla Mlangeni.

Wyatt searches for a while to find precisely the right words for what he finds so compelling about the Blue Notes’ music. Eventually, he settles on a paradoxical combination:

relentless energy – they definitely weren’t a band who looked at their watches to see how long they’d played!

Plus,

being completely comfortable in the free space.

Possibly, that’s a lesson that needs to come home in political as well as musical terms.