Published date

Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

From the book: Johnny Gomas Voice of the working class: A political Biography by Doreen Musson

The decade after 1935 can quite justifiably be called a renaissance in the history of struggle by the oppressed in South Africa after the "dark years" of the early 1930s which Tom Lodge describes as "wasted years". New forces converged with old ones. How to reconcile the class with the national struggle remained the crucial question. The contradiction between the bourgeois democratic and the socialist objectives of the revolution was - as it still is - a question of heated political debates.

With the 'people's front' line which caused the CPSA to move closer to the white Labour Party and the dormancy of the ANC, Gomas and other activists in and outside the CPSA discussed the road ahead: debates and alternative strategies became a priority. For Gomas, the CPSA had become too openly liberal and reformist and was moving too close to the SALP, a party which he publicly exposed as one which "Hates the Native People Most." In the climate of rising fascism abroad, the CPSA pleaded abstractly for world peace. Gomas felt this was too removed from the aspirations and feelings of the oppressed who had to fight fascism at home. He demanded that the CPSA clarify its position precisely with regard to the national question.

On June 1920, 1934, at the Liberman Institute in District Six, Gomas listened to a debate on the national question between the Cape Literary and Debating Society and the Cape Fabian Society. In a report subsequently published in Umsebenzi, Gomas set out to record, in the most explicit way, his own views on the question. Using as a point of departure, the motion by the Cape Literary Society that "organisation along the line of colour is of greater importance to the non-Europeans than on economic lines" he urged his party to adapt itself to the new conditions and not to make any allowances to the prejudices of the white workers in the organisation of black workers. "Clarity on this issue is of tremendous importance for us; for we saw Communists farcically and diametrically opposing each other in this debate. Unity between black and white workers can only come about if the cry for unity in struggle against the exploiting class comes from both black and white workers ... We see on the contrary that organised white labour directly and indirectly comes out with the persistent demand W whites should be employed in the place of non-whites. This obtains to a considerable extent at the present time and this is so because organised white labour lacks international militant class consciousness in its ranks and non-European workers are unorganised, and not pushing for their just demands."

At about this time white poverty had reached its climax with nearly 16 percent of the total white population being classified as very poor. Although quantification of the number of people involved has remained a controversial issue a figure of more than 300 000 has been indicated. Poverty amongst whites presented the state with more serious problems than poverty amongst blacks. 'An analysis by Davies and others places great emphasis on the role played by the state in containing the struggles of white workers Generally, government efforts consisted of 3 elements: a legislative package in the labour market designed to favour white workers at the expense of blacks; the provision of public services to whitest particularly education, health and housing; and thirdly, a national programme of public employment and relief measures.

| Estimated no Of unskilled White bread Winners employed 1933-40 | Estimated of Dependants(2) | Total | |

| Manufacturing | 14 000 | 28 000 | 42 000 |

| Mining | - | - | - |

| Government-sub Sidized employment | 20 000 | 40 000 | 60 000 |

| Railways, unsubsidized employment | 17 000 | 34 000 | 51 000 |

| Other unsubsided Employment | 27 000 | 54 000 | 81 000 |

| Total | 78 000 | 156 000 | 234 000 |

By granting white workers (and whites generally) particular economic benefits the state tried to co-opt them within the legislative machinery. The state was prompted by the fear that white labour unrest would lead to African militancy. The onslaught against white trade unions further coerced white workers to act within the parameters of 'the law'.

According to Gomas there were also fundamental obstacles in the way of black-white unity: "The white workers are so deeply steeped in stinking social imperialism and race-hatred that they refuse to organise with the non-European workers and they assist the ruling exploiting class to worsen the burden of oppression of the non-Europeans. We are not going to wait until the white workers receive the non-European workers in their ranks. This would be suicidal. We shall have to organise the non-European workers by themselves, therefore on colour lines!". Addressing himself to black workers as well as to his Party he continued:

We will lead this struggle for better conditions of employment, against the replacement of non-European workers by whites, for higher wages, for economic and political privileges as enjoyed by whites, for the abolition of slave laws, for the distribution of the land to the landless, for social insurance, for the overthrow of the oppressors' government, for the full right to rule the country as the majority, along with the white toiling masses and for the setting up of a Native Republic in a workers' and peasants' government.

It is important to note that Gomas never excluded the white workers per se: "... as internationalists, we shall not in the least slacken in leading and persuading the white workers to carry on their light in a militant and class conscious manner..."

This latter statement of intent by Gomas was no mere "phrase mongering", to use one of his favourite terms. He never had any patience with policies, words, and theories without praxis . Those who preached without accompanying their words with concrete action were targets of his bitter criticism. He spared nobody; not least his own Party. He was determined to change the Party from the inside at the cost of bitter fights with colleagues, fights which left permanent scars on both sides. He persistently urged his party not to make any concessions to white workers, but to put the choice starkly before them: either with the black workers or against them.

The young Gomas, c. 1913

The young Gomas, c. 1913

"Elizabeth and her son, Johnny, c. 1916

"Elizabeth and her son, Johnny, c. 1916

St Michaels and all Angels School at Abbotsdale

St Michaels and all Angels School at Abbotsdale

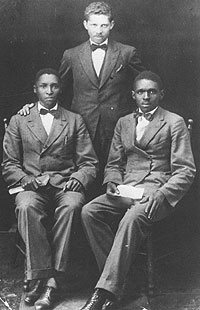

ANC (WC) oficials: Stanley Silwana (Asst Secr); Johnny Gomas (Acting Pres); Bransby Ndobe (Prov Secr, Sept 1928, after release from Roeland Street Prison

ANC (WC) oficials: Stanley Silwana (Asst Secr); Johnny Gomas (Acting Pres); Bransby Ndobe (Prov Secr, Sept 1928, after release from Roeland Street Prison

Johnny Gomas, after release from prison in 1931

Johnny Gomas, after release from prison in 1931

Three officials, 1933: Joseph Ngedlane, Moses Kotane and Johnny Gomas

Three officials, 1933: Joseph Ngedlane, Moses Kotane and Johnny Gomas

5th Annual Conference of the National Liberation League of South Africa. Officials for 1940-41

5th Annual Conference of the National Liberation League of South Africa. Officials for 1940-41

Leading members of the Franchise Action Committee, including John Gomas, Cissie Gool, Reg September and Joe Nkatlo

Leading members of the Franchise Action Committee, including John Gomas, Cissie Gool, Reg September and Joe Nkatlo

Morley Turner and John Gomas, February 24th, 1945

Morley Turner and John Gomas, February 24th, 1945

Officials of the Chemical Workers Union (1941/42). in the 2nd row are: Cornelia Gomas, Bill Andrews, Henry Cookson, Ray Alexander (Simons), John Gomas

Officials of the Chemical Workers Union (1941/42). in the 2nd row are: Cornelia Gomas, Bill Andrews, Henry Cookson, Ray Alexander (Simons), John Gomas

Richard Ndimandi, Mrs Mkwena, Nimrod Kota, John Gomas at Cape Town Gardens, 1964

Richard Ndimandi, Mrs Mkwena, Nimrod Kota, John Gomas at Cape Town Gardens, 1964

Johnny Gomas and his third wife, Cornelia, c.1974

Johnny Gomas and his third wife, Cornelia, c.1974

The continuing ambivalence of his Party on the national question led to the emergence of new political groupings. Two groups opposed to the Stalinist policies of the CPSA - the Workers Party of South Africa (WPSA) and the Fourth International of South Africa (ROSA) - eventually had a political impact quite out of proportion to their numbers, particularly in the Western Cape. Their ideas also had a profound effect on Gomas' later thinking. Some of the persons in these groups had originally left the CPSA (or had been expelled) over the Black Republic slogan. It was only in the light of Trotsky's reply to the Draft Theses of the WPSA that the South African Trotskyists began to lay greater stress on the national character of the revolution. This emphasis later bore fruit in the formation of the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) in 1943. This new shift in the Trotskyists' thinking led to a close ideological bond between Gomas and his "old enemies".

Sinking their temporary differences amidst the great economic depression, Smuts and Hertzog formed an alliance in 1934, of alliance which was to be the vehicle for the entrenchment of segregation. The Hertzog-Nichols Bills which intended to remove Africans from the common voters roll in the Cape and to entrench segregation, jolted even the ANC to life. It was Seme and Jabavu who initiated the call for a convention to challenge the bills. Unity had become the most important refrain among the oppressed. The acid test would be whether politicians could turn the rhetoric 'A reality. The call was, for Gomas, an encouraging sign. Very excited and brimming over with optimism, he left Cape Town for Bloemfontein to attend the "mammoth convention" on Decent 15 -18, 1935, where more than 500 delegates were representative more than 150 organisations. The All-African Convention, call together to discuss Hertzog's "Native Bills", was united in its rejection of the Bills, but divided on the question of what action should be taken. As one of the militants at the Convention, Gore demanded action. His proposal that mass protest meetings b organised throughout the country was unanimously accepted. 81 his expectations were soon dashed. Instead of carrying out Comas; proposal, Seme, Jabavu and others met with Hertzog early in 1936. Hertzog, realising that his original proposals to amend the entrenched clause in the constitution would not receive the necessary two-thirds majority, then turned to the ANC urging a "compromise", i.e. African acceptance of his Native Representative Council (NRC).

According to Michael Harmel, conflicting versions of what happened between Hertzog and the delegation were circulated. Hertzog claimed they had accepted the "concessions" he offered, while some of the delegation members vehemently denied this. Whatever transpired at the meetings, the fact remained that the compromise was accepted, whether "under pressure from the government and some white sympathisers", or not. In addition to the "toy-telephone" NRC, the African vote was also sacrificed and replaced with three white members for the House of Assembly and two for the Cape Provincial Council. In April 1936 the Bill a passed.

In an article called "What Must Be Done Now?" Gomas rejected outright the "peaceful compromising" form of opposition to the Bills as decided by the Convention majority. The Convention "hopelessly ineffective" opposition, its "defeatist, meek and mild pious negativism" had assured the government that the "indignant masses of native people were well under the control of chickenhearted leaders."

Addressing himself to the people, he hammered out the need for an organisation to unite and co-ordinate the actions of the existing organisations, to provide a basis for unity and action, and to keep it the militancy and expectations of the oppressed - a spirit, he claimed "that was prevalent at the Convention from the beginning". The immediate main task then was to make the proposed June 28th meeting of the Convention a "mighty force which must decide to wk out a programme for organisation and action of an all-in National Liberation movement with the general slogan "Equality, Land and Freedom". This movement had to give every assistance to the forming of trade unions for black workers which had to be affiliated to the movement. Although his emphasis was on black unity, Gomas believed it necessary to include the "exploited sections of the whites" in this united front.

Gomas, in his enthusiasm for a united front, underestimated the deep-seated divisions within the AAC. These were represented by at least two divergent policies, which eventually were to lead to two opposing directions in the conduct of the struggle. (See Chapter 6.) The first tendency was represented by the ANC leadership Seme, Jabavu) to whom the task of a political organisation was mainly to be an instrument to exert pressure on the government in older to gain concessions. This made the ANC leadership unable to appreciate the need for an organisation such as the AAC. Seme's letter in the ANC organ Umteteli of April 8, 1936, in which he accused the General Secretary of the AAC and "probably others" of the Executive Committee of being "busy trying to turn the Convention into a permanent national organisation ... in an effort to undermine the African National Congress" evoked a heated response from Gomas:

Surely it must be obvious to any sensible person that the broad representative character of the All African Convention is by far a we competent body to decide what steps to take further for the lights of the African people than the 'African National Congress' ... To talk about 'division' when the Native people as an oppressed people are totally unorganised and when it is so clearly evident the SEA of enthusiasm for Unity and Action created by the Convention at over the country in the ranks of the African people, one could excuse Dr Ka Seme if he would be blind or deaf but not otherwise. What is all-important now is to harness this giant wave of enthusiasm for Unity and Strength created by the Convention in its unanimous opposition to the Native Bills. All over the country all lovers of freedom must prepare the masses to render every support for the June 28th meeting of the Convention whereat must be constituted a Union-wide National Liberation Movement with a 'formulated programme to take up the struggle for the immediate needs and national freedom of the Africans.

The Trotskyists as well as the militants in the CPSA represented the second trend within the AAC. Gomas, ironically, was to find himself more and more in agreement with his "arch enemies", in spite of his regular verbal attacks on them via the pages of Umsebenzi.

At the June 28th meeting the proposals by the Trotskyists, led by Goolam Gool, to boycott the election for the NRC, were rejected by the ANC leaders. After the meeting, many ANC members on the AAC Executive competed for seats on the Council. The ANC also supported the election of white liberals as African representatives in Parliament. In this they were encouraged by the CPSA which also ran candidates for the NRC, as well as for the Cape Provincial Council and the Senate. CPSA leader, George Hardy, attacked "Trotskyists and other opportunists for proposing a boycott of the elections". The attack applied to Gomas too, who was neither a Trotskyist nor an opportunist.

In response the Trotskyists in the WPSA, via their organ, The Spark, challenged the CPSA to explain, in revolutionary terms, how participation in and collaboration with the instruments of the rulers would contribute to the emancipation of the black masses. They totally rejected the line of the CPSA as class collaborationist and opportunist. "It is sad enough to think that this once revolutionary party has sunk so low as to go into a People's Front which excludes the Non-Europeans, which removed from its Agenda the item, 'Native Policy' because in the words of Mr. E S Sacks 'a united front between black and white at this juncture was impossible' ... they rejected too the boycotting of the Council and the Electoral Colleges and advocated that the African Convention should make use of the political avenue opened by the Bills". For the Trotskyists it was patently clear that the CPSA had succumbed "to the bluff of the government and its agents". Gomas, who "hated the system of white representation" and who was always at loggerheads with the Party on this score, fully supported the Trotskyist principle. We notice an interesting psychological drama-taking place in the mind of Gomas: his party was the only active political organisation after the demise of the ICU; it survived the traumatic year of 1929, and was about to mobilize the people on a mass scale for a Black Republic when the spectre of Trotskyism reared its head. Above all, the CPSA was the only organisation which was organising black workers into trade unions. Gomas refused to acknowledge that the convergence of forces had conflated his position with that of his enemies. Trotskyism remained to him a "poisonous swamp". This reiteration of his views was prompted when Manuel Lopes, who had been a member of all the political parties in South Africa - Labour, Nationalist, Communist, FIOSA, Greyshirts - finally drifted back to the National Party in 1937 - facts about Lopes which Gomas himself recorded. In a letter entitled, "Trotskyist Joins National Party" Gomas wrote:

Up to 1924 Lopes was a prominent member of the Communist Party. Together with other opportunists and careerists he was attracted to the Labour Party for the Nationalist-Labour Pact was then in a position to provide 'jobs for pals'. Lopes at that time said that he had joined the Labour Party in order to win over the 'masses' to communism. However, he soon became disillusioned and with a few others, formed the Independent Labour Party. This Party shrunk to the number of four and Lopes became impatient because the world revolution did not come as soon as he desired. He then decided to link up with the advocates of the '4th International' - the Trotskyists who were to bring about the revolution by express order.

By all accounts Gomas was rather ignorant of the ideas of Trotsky, the "Organiser of Victory" as The International affectionately called him. A short resume of these ideas will have to suffice for our purpose in this biography. At issue were the theories of a two-stage revolution and a permanent revolution. We have seen the emphatic instruction by the Comintern (in 1930) to the Party in South Africa to carry through the revolution in two stages: first for bourgeois democratic rights for blacks (via a Black Republic) and at a later stage for socialism.

The thesis of the theory of permanent revolution as it emerged in its final shape (Trotsky had stated it in its essence in 1906 already) can briefly be summed up as follows: In the epoch of imperialism the tasks of the national democratic revolution in the less developed countries can only be carried out by the conquest of political power by the working class, supported by the poor peasants. The conquest of political power by the working class in less developed countries is impossible without the proletariat becoming the recognised political leader of the nation. The peasantry, the urban poor and urban petty bourgeoisie, may support the leading proletariat. The process of cooperation can and should find expression in political united fronts or other alliances in which the proletariat and its party fight for political hegemony.

In contrast to the dogmatism of the Comintern Memorandum of 1930, the theory of Permanent Revolution states that the formation of alliances and fronts cannot be predetermined by purely objective criteria such as, for example, the size of the proletariat in the active population, the relative weight of the urban centres in relation to the countryside and division within the ruling class. It depends on the concrete political alignments in a country, the varying levels of consciousness of the working class and other social forces engaged in the liberation struggle, the weight of the revolutionary vanguard party of the working class and its ability to organise and lead broad masses, including the peasantry. The immovable principle of the theory of Permanent Revolution is the organisational and political class independence of the working class. Any tactic or political action must be directed at increasing the self-organisation and self-emancipation of the working class.

Although there would be some delay between the implementation of at least some socialist, anti-capitalist measures and the full-scale realisation of the socialist tasks, it will not be an indefinite delay, dependent upon objective and subjective conditions.

The permanent character of the revolution is expressed by the fact there is no 'stage' in which the proletariat will not fight or should not fight for its own specific anti-capitalist demands. There is likewise no 'stage' in which the dictatorship of the proletariat can or will abstain from implementing at least some of its demands. The revolution 'grows over' from the fight for national and democratic demands into a socialist revolution, without any interruption continuity ... it is the same state power which implements both.

Gomas, by all accounts, was not familiar with Trotsky's theory, am neither was Lopes and Glass, as can be assessed from the writing of all three. Nevertheless, it was the theory of Permanent Revolution as interpreted by Lopes, Glass and others which Gomas so acidly attacked. Indeed he used Lopes's inglorious career to demonstrate that all Trotskyists were "renegades, opportunists and muddle heads". Notwithstanding his professed contempt for the Trotskyists the overriding issue for Gomas was a United Front of al organisations of the oppressed. Indeed, this question had beer debated by him, La Guma and Ahmed Ismail nine months before the formation of the AAC.

It was at the time when Cape Town was celebrating the centenary of the emancipation of slaves in 1834, that Gomas issued a pamphlet focusing on the sham of the centenary. The so-called emancipation had only made possible a form of enslavement more subtle and deadly than slavery before 1834. "Without land, bread and equality of opportunity, there can be no freedom. After a century, the non-European must still fight for that freedom which should rightfully have been his since 1834".

In that same year there were also Jubilee celebrations for George V's reign. Gomas wrote and issued an article, on behalf of the CPSA, called "King George's Jubilee: 25 Years Reign of Luxury, Pomp and Waste!" Appearing in court, together with Minnie Gool, on a charge of Lese Majeste for having "impaired the dignity of the king" by calling the latter a "parasite", Gomas used the court to advocate his ideas. "We are solely concerned with King George or any other King or Royal family as representing an historical, economic and political regime. King George may be a nice man personally, the same as I think General Smuts is a nice man personally. But they both represent an institution of government that is most cruel, undemocratic, oppressive, uneconomic and gluttonously greedy... therefore King George is parasitical on the backs of all toilers in the British Empire and hence the Communist Party is out for the abolition of this institution" and to replace it with a real democracy, "not like those in Western Europe, where the people also got rid of kingship and established republics, but like in the Soviet Union where the workers and peasants are in power under the leadership of the Communist Party." Found guilty of Lese Majeste and sentenced to six months hard labour, Gomas appealed and demanded in an affidavit the testimonies of the Premier, Hertzog and the 'Purified' Nationalist Party Leader, D.F. Malan, on the legitimacy of propaganda against British rule and the Union Jack. The conviction and sentence were finally squashed by the Supreme Court.

Gomas afterwards, in an article in The Sun, was at pains to explain that the opposition of Malan and his N.P. was merely academic opposition. "Would the National Party tight along with the non-European people for, we will say, an Independent Republic, for the confiscation of all properties of the British imperialists, for the distribution of the land of the rich landlords and land companies to 'he poor black and white farmers and for equal and democratic rights of the black people? ... But the activities and policy followed by Dr Malan and his party have proved to be only another Imperialist policy."

The gist of the pamphlet The Emancipation of Slaves' written by Gomas appeared in the preamble to a draft programme of the National Liberation League called, 'For Equality, Land and Freedom'. The NLL was founded in Cape Town on December 1935. The founding members of the NLL included Gomas, La Guma and Cissie Gool. Although largely coloured in membership the NLL emphasised the need for black unity in the struggle against a common enemy. It analysed the system of oppression in South Africa as inextricably linked with imperialism which led to a rejection of all white political parties. It stated uncompromisingly "the task of freeing the oppressed is the task of the oppressed peoples themselves". In its programme of demands it emphasised complete equality, unity of all oppressed and the need for boycotts, strikes and civil disobedience and non-European leadership.

While waiting for the next conference of the AAC due in December 1937, Gomas concentrated on the activities of the NLL which made impressive strides in the Cape Peninsula, particularly among the youth and students. Halls where NLL meetings were held were always packed with high school students. On his return from Johannesburg after having failed to be re-elected on the Party's Politbureau, Gomas and his second wife, Mabel, whom he had met during his stay in Johannesburg, moved into no. 27 Stirling Street in District Six. Towards the beginning of 1937 he left Mabel and went to live in a house in the Maitland-Salt River area where he regularly "brain-washed the youth". All these "brain-washed" young people joined the NLL. Lectures were prepared by especially Gomas and Charles van Gelderen, and taken to schools by the students. Branches were also formed outside of Cape Town.

By mid-July of 1936 Gomas went on a tour of the Cape, addressing many open air mass meetings and setting up NLL branches. By July 1936, "The National Liberation League had invaded Port Elizabeth" where large numbers joined. A branch of the NLL was formed under the chairmanship of S Koloi with W D L Matini as treasurer. Resolutions of the first Port Elizabeth branch welcomed the second meeting of the AAC, calling upon the delegates to assist in "solving the most burning question of organisation for the oppressed African peoples by forming a national liberation organisation ... (and) by adopting the programme of struggle for the national rights of the oppressed - under the slogan, Equality, Land and Freedom ".

The elected committee of the NLL branch in Port Elizabeth took up specific issues. The first local issue was related to the "most deplorable sanitary conditions" which were "a disgrace to modern civilization ... the streets are dirty and without lights at night. These and many other grievances of the local residents will require the immediate attention of the League Committee and will have to be taken up with the local principal authorities ."

The campaign in Port Elizabeth was taken up under the leadership of Matini and Tshulltz who went on regular tours to Uitenhage, Salisbury Park, Walmer Location and Gibsonville. They claimed to have strengthened branch membership considerably by emphasising local issues: "Join the League, let us demand better streets in Korsten. Let us demand more lights in Korsten. Let us demand drainage in every street in Korsten. Let us demand that our letters should be delivered to every house in Korsten, as citizens of Port Elizabeth."

In April 1937 2 000 people gathered in Cape Town under the aegis of the NLL to protest against discriminatory legislation. Those present approved of the speakers' exposure of the Government's evil intentions "to rob, filch and debar non-Europeans from their rights". The laws at which the protest was aimed were: the Marketing Bills which provided for setting up of boards of control and pricing of agricultural products, from which non-Europeans' farms were to be excluded; and the Native Laws Amendment Bill which was an amendment to the Urban Areas Act which would give the Minister of Native Affairs power to expel blacks from one town or location to another. Native voters in the Cape would also be deprived of the right to stay in towns outside the segregated Native locations and be forced to introduce stop orders for the deduction of rent from their wages. Other laws against which the protest was aimed included the Anti-Mixed Marriages Bills, the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill and the Provincial Legislation Powers Extension Bill.

At the first Congress of the NLL held at Cape Town on March 28-30, 1937 the following resolution was passed:

This First Congress of the National Liberation League of South Africa, having in mind the efforts of certain leaders of the white working class to further divide the movement of the oppressed people against imperialism by advocating division on social lines and in addition the efforts of imperialists to draw away the white worker with such concessions as the 'civilised labour policy' and other anti-colour legislation, points out the urgent and dire necessity for the conscious white worker and Socialist leadership to educate their followers upon the impossibility of achieving freedom from imperialism without unity of black and white in South Africa. We, here assembled, pledge ourselves to do all in our power to build anti-imperialist movement of the non-Europeans with the aim of eventual unity with the white worker for the overthrow of imperialism in South Africa.

With the impressive increase in membership, Gomas had reason to be optimistic about the future of the NLL. "With the spreading of League branches throughout the Union of South Africa the struggle for the general betterment of the conditions of the 7 500 594 oppressed non-European people, will go progressively forward." But his optimism was to be shortlived. The NLL was not an ideologically homogenous organisation but rather consisted of at least two factions each consisting of what has been called "a coalition of various factions". One faction, mostly CPSA members or CPSA-influenced persons, stressed the building up of working class unity and participation in parliamentary and local government elections. Their rhetoric of non-European leadership was to be challenged by a few rebels, among them Gomas. These rebels felt that not enough was being done to train and allow radical blacks in leading positions on the executive of the NLL. Reformist white CPSA members, they believed, dominated the executive. These rebels were eventually to team up with the 'other faction' in the NLL. Some commentators as the “purists" referred to the other faction, led by the Trotskyists under Goolam Gool. Their views were espoused in The Liberator, an NLL organ published for the first time in March 1937 and for which Gomas wrote a number of articles in which he urged black working class leadership and unity. Entitled 'an anti-imperialist magazine', The Liberator consistently attacked imperialism throughout the world. The Trotskyists did not object, in theory and principle, to the presence of whites in the leadership. They objected, in the words of Goolam Gool, to "the present reactionary and reformist policy" of the communists who were quite prepared to sacrifice the principles of the League in order to win elections.

It was the Gool faction that tried to gain control of the NLL. Gomas uncomfortably found himself more and more in ideological agreement with these Trotskyists. At the same first national conference of the NLL in March 1937, "seven persons in revolt sat down to draft a programme expressing the aspirations of the non-whites ... It was felt that there was not sufficient effort being made by the white worker and socialist leadership to combat the effect of the pernicious policy upon the movement for the unity of the two sections of the working class movement. " The seven persons included besides Gomas, also La Guma, A Brown, and H.M. van Gelderen (twin brother of Charles). The rebels then caucused, particularly amongst the student members, to get a motion passed to oust Sam Kahn, Morley Turner and Harry Snitcher from the NLL Executive. These three were the only whites on the executive and they were all CPSA members. The attempt to oust them was motivated by the need for radical black leadership. However, the rebels failed, because the financial resources at the disposal of the president, Cissie Gool, enabled her to provide transport for her supporters who packed the hall, and the motion was overruled before being put to the vote. The next issue of The Liberator demanded a change of tactics in the struggle: Cap-in-hand deputations, pious resolutions and demagogy as weapons of struggle against oppression are obsolete and must be relegated to the reserve. To the front must be brought MASS ACTION. The masses must be activised to take up the struggle themselves. Such a change obviously necessitates a change of leadership. It is clear that our present reformist leadership will ml jeopardise their 'social standing' to deviate one inch from the political rut of decades. Neither can the 'collaborationists' be expected to discard their hopes of gaining, what, from the imperialists, we are unable to conceive.

By the end of December 1937 the NLL had undergone major changes. Its organ, The Liberator, was being printed now and not cyclo-styled; while its approach had changed from militant, anti-white to a more moderate one, focusing more on economic trade union issues. It would appear that the NLL had been captured by the CPSA, which gave the latter the chance to regain a foothold in black politics. Its president, Cissie Gool, became a member of the CPSA in 1939 and in the same year joined the Political Bureau of the Party. She was originally much influenced by Gomas, according to Gool's biographer. Gomas had introduced her to working' class ideas and convinced her of the need for a "united working class front". Under her leadership the "NLL immediately plunged into 'reformist' political activity" focusing on support for the CPSA policy of electioneering. Gomas blamed the split in the NLL on the failure of the 'intellectuals' to "do some spade work and tackle the immediate demands of the people".

From the correspondence between Gomas and Moses Kotane, it is clear that Gomas was still pinning his hopes on the AAC which became a permanent organisation with its own constitution in June 1936. The third conference of the AAC in December 1937 again underlined the deep-seated differences between the ANC-CPSA on the one hand, and the Trotskyist faction on the other Gomas did not attend the conference. Apparently he had generous stepped down to allow Kotane to be delegated to the conference. One informant contends that Gomas had to be generous, as he had incurred the wrath of the Party because of his leanings towards the Trotskyists. He could not be seen to vote with his enemies. At this conference Kotane became a "CP star". He kept Gomas informed by letter. Writing to Gomas from Bloemfontein, Kotane re proud to have his newly found popularity recorded. "So the Communist Party had a third star shining at the Convention besides Mofutsanyana and Radebe. Therefore the Cape Town DPC did well to send me there, but all thanks and congratulations are due to JSG for his unselfish act." Unity amongst the Western Province delegation, consisting of delegates from the CPSA and the ANC, was, according to Kotane, achieved in the train to Bloemfontein However, this "miraculous agreement" soon came to an end. "The agenda is atrocious, full of omissions and badly arranged. The leaders of the ANC are scared out of their wits and they neatly diverted the purpose of the conference by dealing with the question of the protectorates." With the ANC-CPSA opposed by a self-assured and united Trotskyist faction, led by Goolam Gool, the conference was set for more 'miracles'. Two days later Kotane was more optimistic. "I am not disappointed with the Convention at all. Be it what it may, it has come to stay... 'Revolutionaries' may be disappointed but those who have a little knowledge of Africans and African affairs and attitudes have ground to be optimistic." The ANC-CPSA had found each other again. The Trotskyists hammered their position away, trying to urge a policy of non-collaboration on the AAC. On the other hand the ANC-CPSA faction was careful to make sure that any changes in the system of oppression would not be too traumatic for whites. From this position stemmed their rejection of the policy of non-collaboration. The reformists eventually won victory. The Trotskyists were out-voted on the decision to participate in the NRC or to boycott it. In its new constitution, a clause provided for the recognition of the NRC members as the official mouthpiece of the AAC. Kotane's astute observation was confirmed: "You will unmistakenly see or notice that the Convention is moving to the right. However, not too bad. There is in it a strong tendency and willingness to organise. No! Do I hear you saying to phrasemongering?"

The extent to which the AAC was guilty of "phrase mongering" was he soon to become evident. After the conference the ANC fell back into the limbo, while the Trotskyists declared their intention of making the AAC or part of it a permanent body which would provide the leadership to the leadership to the black masses. They hoped to convert the AAC into a federal national body by using their control of the Western Cape Committee of the AAC.

Gomas, in an effort to maintain the fragile unity within the AAC, used the pages of Umsebenzi to propagate unity. On August 13, 1937 an article by Cedric Dover, who was a political activist in Britain and who is best known for his book Half-Caste in which he explodes the myth of 'race', appeared in The Sun. In this article Dover appealed for "coloured unity", meaning Africans, Coloureds and Indians. Responding passionately to the article, Gomas drew attention to the increasing oppression of the blacks, a process in Gomas which he said "the few progressive forces among the white people threaten to be overwhelmed by the aggressive racialist agitation in dorp and town". He furthermore pleaded for the priority of the besides struggle over personal aggrandisement. "Personal prestige and did well self-interest must be sacrificed for the cause of national liberation and eventually "for the preparation of a world congress of oppressed Province Coloured and colonial peoples."

Gomas's plea for priority of the struggle over a comfortable life was rigidly applied to his own life. He also rather naively expected end the same degree of commitment and dedication to the struggle from others as he himself was prepared to give. It was this "fanaticism" which earned him the scorn of some contemporaries who felt that he was not even trying to strike a balance between his personal commitments to his family and his political commitments. In Gomas's mind however, and as his actions demonstrated, family life was secondary. This attitude of his was also revealed by the lack financial provision he was often guilty of. He must have appeared especially harsh and unfeeling, even irresponsible, in the light of his second wife Mabel's weak physical constitution, which made it impossible for her to work and so earn an income. In these "earthy matters of providing for the home, it was Elizabeth who had to keep the wolf from the door, while her son concentrated on matters of higher calling.

Still with the aim of unity in view, the NLL called a conference in Cape Town in March 1938. The Stuttaford which was before Parliament at the time intended to introduce segregation measures; and the Cape Provincial Council passed a measure granting to town councils in the Cape the right to introduce segregation in transport services, housing and in public places. At this national conference a broad front organisation, the Non-European United Front (NEUF) was formed which demands] the repeal of the racist, segregationist laws, and it organised a mass demonstration in March 1939. Accompanied by his sickly Mabel, with whom he was reconciled, Gomas, Morley Turner, H Snitcher, John Paulse and Cissie Gool rode to the Parade to joint 10-15 000 protesters. From the lorry arose the strains of "Dark Folks Arise!", a freedom song written by Gomas and La Guma. From to Parade about 5 000 protesters marched to Parliament where they were met by a police baton attack. The protest did however achieve its aim: the proposals for further segregationist measures were dropped - for the time being at least. The Coloured Affairs Department (CAD) was only introduced after the National Party victory in 1948.

Shortly after the Big March, Mabel died, in the same month to Elizabeth also lost her second husband. Still in mourning, gomas attended another NEUF conference in mid-April 1939. Although dominated by CPSA members, also present were members from FIOSA, for example H.M. Van Gelderen, and from the New Era Fellowship (NEF), for example Ben Kies. The NEF was a student society strongly influenced by the Trotskyists. The fellowship organised regular discussion meetings for young people in the Western Cape. Discussions were of an "exceptionally high intellectual" standard. Leading figures in the NEF read like a Who's Who of the left in South Africa in the 1940s and 50s: Goolam Gool Ben Kies, R E Viljoen, A Fataar, Rev. D M Wessels. It was these young intellectuals who had much influence over the younger generation of coloureds. Gomas was one of the few of the older generation' who was attracted to their ideas, especially the ideas of non-collaboration, which in its classical formulation described a course of action whereby the oppressed people refused to work the instruments of their own oppression. It recognised the irreconcilability of the interests of the oppressor and the oppress and excluded any "unprincipled combination with the rulers and their agents ".

The outbreak of the war in 1939 exposed how removed his Party' had become from the basic interests of the masses it claimed to represent. To the CPSA the choice was plainly and simply between fascism and democracy. "What democracy?" Gomas queried. In 1942 the CPSA launched a "Defend South Africa" Campaign. The Trotskyists on the other hand maintained that although the Soviet Union's involvement in the war necessitated a call for the military defence of the USSR, it did not change the character of the war between Allied imperialist states and Germany and Japan. It remained an inter-imperialist war for a redivision of the world's markets and colonies. Gomas was echoing the Trotskyists when he pleaded for the intensification of the fight against the oppressors at home. From then onwards he would be seen much in the company of his old enemies.

In 1941 Smuts had threatened the setting up of a Coloured Affairs Department (CAD) and a Coloured Advisory Council (CAC) on the model of the NRC. In 1943 the Cape Coloured Permanent Commission (CCPC) was formed, consisting of coloured representatives from all four provinces. The main motivation for the Government behind this collaborationist strategy was to try and co-opt coloured support, placating their demands for political rights and improved economic conditions. In return coloureds were promised more employment in the civil service, educational reforms and protection from cheaper African labour. In 1943 an Anti-CAD committee was formed with the main objective of preventing the Smuts Government from forming a CAD. Over a period of three years, activists, consisting in the main of students, teachers, a few doctors and a sprinkling of workers, penetrated organisations ranging from trade unions to sports bodies, and cultural societies.

The New Era Fellowship called a meeting on Saturday, February 13, 1943, at the Stakesby Lewis Hostel in District Six. As a member of the Anti-CAD Committee, Gomas had much contact with the New Era Fellowship. The meeting at the Stakesby Lewis Hostel was the largest ever attendance attracted by the NEF since its inception in 1937. Gomas was sharing the rostrum with Ben Kies, Allie Fataar and Isaac Tabata. To find Gomas on a stage with his official ideological adversaries, the Trotskyists presented an important step in the development of black politics during these years. The People's Front Line which led his Party to pursue an ill-white popular front alienated Gomas from the Party. Its primary goal of black-white unity also receded into the background as the Party entered the field of parliamentary politics. For Gomas it represented the end of an era during which the CPSA played the dominant role in black politics, and the beginning of a new dawn. Black unity had become the key word. Looming large in Gomas's consciousness was the concept of black power. In a hard-hitting he attacked the CAD, CAC and CCPC. The "new scheme" said Gomas "was a perpetuation of the white labour policy as announced by Hertzog in 1928". Condemning the participants in the Council, he urged the audience actively to resist. "These gentlemen of the Council, noted for their subservience to our oppressors, will play Quislings to seal our doom. We must not only protest. every Coloured person must be an active member organised to break down this fascist scheme." After this meeting, the Anti-CAD Campaign was launched by the Anti-CAD Committee. Innumerable rallies and meetings were held throughout the Western Cape drawing thousands of protesters - and the Government's plan came to naught. A dummy Coloured Advisory Council was instituted which functioned fitfully until 1948 when the NP Malan formed the CAD; regardless of its rejection by the people it was supposed to serve.

The Anti-CAD Campaign did much "to politicise and mobilise" the coloureds and it also led to more clearcut political alignments in the ranks of the oppressed and which fundamentally centred around the policies of no-compromise and non-collaboration. Gomas fully supported the policy of non-collaboration, but as a 'pragmatist', he also insisted on direct action. Propaganda without concrete action was not nearly enough for him. The Anti-CAD, he believed and urged, should involve itself at all levels of the struggle. The attitude of the Anti-CAD towards the Municipal Elections of 1943 demonstrated to Gomas their "lack of a positive lead".

The Municipal Elections in Cape Town in 1943 were the first to take place since 1938. For Gomas, who was a CPSA candidate, the election in Ward 7 part of District 6 where he lived was particulary important for three reasons: a black person could be returned to the City Council; secondly, a representative of the working class could for the first time be in a seat of power; and thirdly, the opposition was a CAC man, S Dollie. Matters, however, became complicated when, like a bolt from the blue, a Mr. W H Willenberg also came forward as a CPSA candidate. He had joined the CPSA in 1939 during the People's Front Line. Although Willenberg had "no political record policy", as Mr. H Holmes of the Lansdowne Ratepayers Association pointed out he was known for having founded two "Christian football clubs" back in 1924, and as a property consultant confessed that it was "impossible for him to practise a boycott" CAC men, although in principle, he was against them.

The crucial problem for Gomas and for the Anti-CAD was how to ensure the defeat of the "CAC man, Dollie". A split vote, between Gomas and Willenberg, would mean victory for Dollie. The action if it could be called that that the Anti-CAD took was to an open letter of muddled protest to the "Non-European Voters. The letter gives an idea of the "dilemma" of the Anti-CAD. On the one hand, it fought against "collaborators" such as Dollie; on the other hand it could not be seen to support a CPSA candidate, even he was a member of the Anti-CAD Committee! The frequent appeals by Gomas for an urgent conference of all black organisations in Ward 7 and for house-to-house visits were rebuffed by the Anti-CAD. "The issues in Ward 7 are," Gomas wrote, "in fact, national issues and affect the entire non-European population, not only in the Cape Peninsula, but throughout the Cape. In the interests of the movement of National Liberation and the fight against Colour bars; it is essential that the fight in Ward 7 be placed in a proper perspective. The election must become the means of uniting our people and not dividing them." This was how Gomas was entreating the Anti-CAD to give a positive lead in the elections, but the Anti-CAD could not be moved. Its policy of non-collaboration was leading it into a cul-de-sac. It became the practice to behave as though those who boycotted were non-collaborators and those who did not boycott were collaborators. In its secretary's report, the Anti-CAD excused itself for failing actively to support the CPSA candidate against Dollie, because it could not turn the Anti-CAD movement into an election machine, nor could it elevate the Ward 7 election to the position of a national issue. Furthermore, the Anti-CAD refused to be drawn into a struggle which took, as Ben Kies expressed it, "up the most idiotic things such as do the non-Europeans get enough vegetables in their soup ... instead of hammering away at the basic political causes." A week or two before the elections, Gomas withdrew his candidacy for the sole reasons of rot splitting the vote against the "CAC man". The election campaign that followed was probably the most abysmal in the history of Cape civic politics with the two candidates fighting on a "Christian-Moslem" issue. Willenberg, with a slogan of "Christian social justice in the affairs of the city", won by a majority of 3 votes, a victory contested by Dollie on the grounds that ineligible votes were cast for his opponent. He only withdrew the charges when Willenberg too threatened to prove that ineligible votes were cast for Dollie.

In a prominent article in the Cape Standard entitled, "We Must Not Fail: Criticism of the Struggle Against the CAC", Gomas set out soberly and frankly the passion of old seemed to be lacking to teach the Anti-CAD how to conduct a political struggle since "the lead given by the Anti-CAD Committee in the fight against the CAC is obviously too narrow and inadequate to face up to the station." It was this narrowness, sectarianism, and what Gomas also referred to as an ultra-leftist line, which rendered the Anti-CAD quite impotent. He lauded the lucid analysis and the correct lessons drawn by the Anti-CAD, but "by confining its activities [the Anti-CAD] to holding protest meetings in ... backyards and ignoring the CAC boys in so far as our interest permits, ... an isolationist policy of 'struggle' cannot gain us anything and must demoralise our forces. The segregation walls of Jericho will not tumble over by us making minute analysis of what materials the falls are composed of." Always suspicious of "phrasemongering", Gomas urged the Anti-CAD again to broaden and to seek full cooperation of the Trade Unions, the CPSA, organisations of Africans, Indians and "sympathetic Europeans" on a basis of "a practical policy of struggle against the day to day discriminations which will blossom forth in greater strength into a non-European united mass struggle against oppression."

Interpreting Gomas's criticism of the manner in which it was conducting the struggle as an attack on the Committee (of which Gomas was also a member), the Anti-CAD avoided Gomas and instead launched an attack against the Cape Standard. This Caps Town newspaper saw itself as the voice of the coloureds and reported quite extensively on the activities of the NLL, NEUF and reported the 1940s of the Anti-CAD. It could also be seen in rivalry with The Sun. The Anti-CAD now questioned the loyalty of the newspaper because it had given "undue prominence to a public attack on the Anti-CAD led by Mr. Gomas...". Gomas later apologised to the Central Committee, acknowledging that he should first have brought his views to the committee.

From the Anti-CAD attack it seemed that two main issues were at stake. Firstly, there was the question of collaboration versus non-collaboration. In theory and practice, the anti-CAD policy of non-collaboration forbade "unprincipled combinations" i.e. co' operation with organisations on the basis of expediency rather than common principles. This policy thus prevented the anti-CAD from working with reformist organisations such as the CPSA. Non-collaboration vis-a-vis the municipal elections was a thornier issue for the anti-CAD. The anti-CAD stood aloof from any overt support for participation, but neither did it propose a boycott. In his onto Gomas made it clear that such an attitude amounted to "a lack oil positive lead".

The second issue centred on the participation of whites in the unity struggle. The Anti-CAD equated the inclusion by Gomas of the “poorer-paid whit workers" in the unity programme with inclusion of white liberals. For Gomas, this should not have been an issue at all, since in the struggle for non-racialism whites could not be rejected per se. Gomas differed with his Party only on the emphasis of this - for the Party, inclusion of whites remained the overriding question. For Gomas, the struggle of the oppressed rested with the oppressed, but whites could not be excluded it principle. The next few years would demonstrate to Gomas whether a compromise could be reached between his position and that of CPSA.