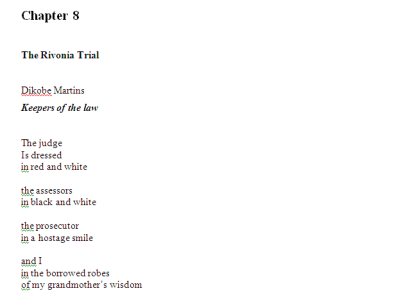

The judge Is dressed in red and white

the assessors in black and white

the prosecutor in a hostage smile

and I in the borrowed robes of my grandmother’s wisdom

corn she said cannot expect justice from a court composed of chickens …

The day after our 90-day imprisonment ended our lawyers - Bram Fischer, with Joel Joffe, Arthur Chaskalson and George Bizos - arrived at Pretoria Prison. The surprise was that Nelson Mandela had joined us. He had been sentenced to five years imprisonment in 1962 for leaving the country illegally and for organising a general strike. He was already serving his sentence in Robben Island prison, yet here he was with us for what became famously known as the Rivonia Trial in Pretoria. I had met him when he had visited Cape Town to tell some of us the necessity and prospects for armed struggle. I had previously met Bram but I did not know the other lawyers. They wanted to know what we had been charged with because the police would not tell them. Whatever the charge was, they said, the future was bleak.

The media were full of government-sourced stories that we were without doubt guilty of the most dreadful crimes and would surely be executed. At this point we were more interested in finding out about each other than going into detail about legal matters.I felt immensely relieved that the 90 days were over. I had previously met Elias Matsoaledi and now met Andrew Mlangeni for the first time. These two comrades had not been at Liliesleaf farm and were arrested in Soweto before being held in Pretoria Local. There, they told me, they had been able to look into our “white” exercise yard and had wondered who the comrade in leg irons could be. Cape Town comrades had told them that I was Comrade Goldberg and I was certainly pleased to meet them. Joel Joffe reveals in his book about the trial that I said from the beginning that, if it would help to protect Nelson and the other top leaders, I would accept responsibility for exceeding my instructions about the weapons manufacture. They looked at me somewhat blankly and did not answer. For my part, the offer was a spontaneous suggestion, made not from bravado but from a duty to protect the leaders. They on the other hand would not allow me to take the blame for something we were all involved in. Such wonderful comrades are a rarity and we had many such rare people.

One point was immediately clear: Bob Hepple was in an invidious position because he had told us he was considering whether to be a state witness, yet he was with us during our opening consultation. He withdrew from the consultation. I don’t remember thinking very deeply just then about him giving evidence but still hoped that he would not do so. The next day we were taken to court and formally charged, as the National High Command of MK, of being involved in a conspiracy to overthrow the state by force of arms; of preparing to receive a foreign army of invasion; and two other charges relating to buying farms and vehicles; and other activities that served the conspiracy and activities in support of the policies of the banned African National Congress.

Even within the shadow of the gallows - we all expected to be hanged - there were moments of relief and humour. Nelson Mandela, for example, and his clothes. Nelson had always been a very snappy dresser, in well-cut, tailor-made suits. Now here he was, appallingly thin with sunken cheeks and wearing prison clothes. Not just clothes, but clothes designed to humiliate African prisoners: short trousers, sandals with no socks, a “houseboy’s jacket” and handcuffs and leg irons. Yet he drew the ill-fitting prison clothes around him and made them look elegant. He was still Nelson, tall and strong, concentrating his stare on the judge. I had a small slab of chocolate in my pocket, something awaiting trial prisoners could have. I stood next to Nelson and nudged him to look down at the chocolate in my hands. He nodded ever so slightly. I broke off a piece and put it in his hand. He wiped his handcuffed hands over his face and I could see the little block of chocolate making a sharp bump in his thin cheek. He sucked it until it melted away, then nudged me for more - and so it went until all the chocolate had gone.

Gradually we came to understand the magnitude of the case against us. There was a mass of documentary evidence, and oral evidence - much of it extracted from witnesses under the duress and torture of the 90-day detention law. There did not seem to be much hope of our avoiding the gallows, yet our defence was a political one, to show why we were prepared to act against the oppression of apartheid and for equal human rights, together with showing that, though we were considering taking up arms for a full-scale uprising, this had not been agreed on.

How fortunate South Africa has been that people like Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada and the rest of us, instead of being martyrs to a cause, have been part of what became a negotiated transition. How fortunate too for South Africa to have had lawyers like Joel Joffe and the rest of the defence team to play such an important role in the defence of democratic norms and the transition from oppression to democracy.Joel Joffe and his wife Vanetta were about to leave South Africa to settle in Australia when he was asked to become the attorney in our trial. They felt they had a duty to stay to contribute to upholding the right to a fair trial of prisoners accused of crimes against apartheid. They agreed that Joel should defend us at a time when few other attorneys were prepared to help in the face of a media campaign of vilification designed to maintain the system of white racial supremacy at whatever cost. Courage takes many forms.

The Joffe’s showed how ordinary people can become extraordinary in times of crisis. Joel himself would not speak about himself in this way. He is far too modest for that. He writes in his book on the trial NOTE The State versus Mandela and seven others, Oneworld Publications that he told Hilda Bernstein, who asked him to defend us, that according to the media we were very unpopular and he did not see much prospect of a successful defence. Hilda took him to task, pointing out that among the black majority we were very popular indeed. He says he realised how easy it was to slip into the habit of taking what the white-owned and apartheid-aligned media said as being all there was to be said. The members of our defence team were quite outstanding lawyers and people, led by Bram Fischer, one of the greatest advocates of his time. He was also a remarkably brave man, taking on the defence at the trial when he was himself part of the High Command. He knew throughout the trial that the state could, at any point, reveal his membership and so ruin him personally.

Yet he persisted with his public role, concentrating before all else on the defence before the court. I knew of one typical example: I had left a small delivery van, the farm vehicle, in the garage at the Kreel’s home in Mountain View where I had been living. Found there it might have incriminated them. Bram at night, on his own, pushed it out of the garage and coasted it down a quite steep hill for as far as he could get it and then abandoned it in a little side street. Clearly there was a conflict: Bram was senior counsel for the defence, therefore part of the state machinery, while being a valued comrade. He resolved these conflicts in the only way consistent with his belief in freedom: he acted as a revolutionary - and it is in action, ultimately, that these moral conflicts are solved.

Bram came from an Afrikaner aristocracy but broke with his people to become a political activist. Having literally saved our lives in the Rivonia trial, he was later himself sentenced to life imprisonment and died of cancer while still a prisoner.Another veteran of the earlier Treason Trial who joined the defence team at Rivonia was Vernon Berrange, an acknowledged expert at cross-examination. A World War I pilot, racing car driver, adventurer and political activist. Berrange came out of retirement to join the team, alongside George Bizos, who had come to South Africa with his father after escaping from fascist Greece in the 1940s. At the time of our trial Bizos was a relatively junior advocate who combined his passion for freedom with a sharp legal mind and a great insight into the State Prosecutor’s thinking. This was all combined with great humanity and a wonderful sense of humour. Arthur Chaskalson was also at that point a relatively junior advocate who had a remarkable capacity for fearless logical presentation and argument. All our lawyers had an enormous capacity for detailed analysis and commitment to those they were defending. More than that, they all understood the historical significance of the trial.

In particular I believe that all of our lawyers showed that ordinary people of integrity can become extraordinary defenders of democratic rights by being prepared to uphold the rights of unpopular political opponents of the regime. George Bizos in his autobiography notes that if we had lived in a completely fascist state the lawyers would have been helpless to assist us. But apartheid South Africa needed the support of the major western powers and thus needed to present a façade of acceptance of democratic norms and, as Pallo Jordan points out in a note to me, South Africa, unlike other colonial regimes, had a democratic system for whites and that caused stresses and strains when seeking to be totalitarian in relation to the colonised and opponents of the system. I am indeed a lucky fellow. Adding a note of splendid gentility to consultations in an office in the prison, George Bizos brought packets of Vienna sausages, gherkins and sweetmeats. That made us feel great and we were able to proceed like a family gathered together to resolve a few minor problems rather than battling to save our lives. Our attitude from the beginning was that if the apartheid state wanted a show trial then we would show them! We would show the world that apartheid was an appalling system of racial injustice and a threat to democracy everywhere.

On the day appointed for the start of the trial our lawyers challenged the validity of the indictment. It was indeed quashed as invalid in law because we were charged as “The High Command” whereas we should have been individually charged as members of a conspiracy called the High Command; and the prosecution had not given sufficient details to enable our defence to know who was charged with what activities on behalf of the conspiracy. It seemed to us that the prosecutor had looked for a great headline and had ignored the rules of criminal procedure. Technically, after the indictment had been quashed, we were free because there was no charge against us. I had a great moment as we were leaving the court. Prison officers and security police tried to herd us down the steep stairs to the cells below. I simply stood there. A rather obese cop tried to shove me down the stairs and I dug my elbow into his fat guts. His breath exploded out of him and he threatened to charge me with assault. Joel Joffe intervened to tell him to stop assaulting me. The fat cop threatened Joffe. Captain Swanepoel watched this for a moment with narrowed eyes and then put his hand through the mob around me and, touching me on the shoulder, said he was arresting me, and the others. We were taken back to the prison, charged individually with sabotage.

A new, equally faulty indictment was presented but Judge Quartus de Wet was by this time fed up with the delays. He ordered the trial to proceed. The prosecutor dropped a bombshell when he smugly announced that Bob Hepple would be a state witness. This was politically devastating, even though we knew it was coming. In our cell under the court Bob again told me that the case against him was so strong that he had to do anything he could to avoid the death sentence. I understood that, but also knew that my life was at risk, the more so if Bob were to give evidence. He said in a recent documentary about the trial that it was his plan to be released on bail so that he could leave the country. He said further that he had initially made a very weak statement to the police which they rejected. He then wrote steadily for 48 hours, making a very detailed statement that they accepted as the basis for his becoming a witness for the prosecution. However, things turned out differently. He did not give evidence in court because Bram went secretly to see Bob and told him to that he could not give evidence because keeping his word to the movement was more important than keeping his word to the prosecution. Bram actually made the arrangements for Bob to go. As an officer of the court and a defence lawyer, Bram should not have contacted a state witness, but he showed again that his loyalty was to liberation rather than the institutions of the oppressive state, for there would have been serious consequences if Bob, with the knowledge he had of our operations, had given evidence. After he got to Britain Bob sent me a birthday card - I wrote to Esmé to tell her that I did not want to hear from Bob again. Was I too hard on him? Perhaps so, but I too was then under enormous pressure.

Bram, incidentally, dropped out of the proceedings for a while in the early parts of the trial because some of the early witnesses in the trial were workers at Liliesleaf farm who might have identified him as a frequent visitor. He set about saving our lives and succeeded through the way he conducted the case. The trial was a remarkable experience of fortitude and principle and courage, just as my comrades Nelson, Walter, Govan, Ray Mhlaba, were remarkable people and great leaders. Similarly Rusty Bernstein, Ahmed Kathrada, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni. They showed great dignity under nigh intolerable circumstances. Courageous too, and clear thinking. And there was time for fun. I had some ancient wire-rimmed glasses that were part of my disguise. They looked like the glasses African pastors typically wore to read from the Bible. Pastors are mfundisi, derived from a word meaning “one who teaches.” Elias Matsoaledi would put my glasses on the end of his nose and pretend to read until we collapsed amid shrieks of laughter. Walter Sisulu needed new glasses but was not permitted to have an optician fit them. Rusty Bernstein and I, with no equipment but sticky tape and a ball pen, were able to mark the positions of his pupils so that the bifocal lenses could be properly fitted into his new frames. And then he would look up and down to find the correct angle for reading or looking into the distance so I am not sure if we really got it right.

Bram told me that it had been decided that I should try to escape again. There would be people waiting for me to drive me away into hiding. I did not ask who had made the decision - it was sufficient that Bram told me about it. My concern was that, if I went, the police would go for Esmé again. After some days during which he consulted with others he said I should ask her to go into exile with our children. When I asked her to go it was at a visit in the prison while surrounded by guards. I could not explain the real reason and so overcome her objection to leaving me while I was still on trial – people would see it as a desertion, she said. I simply insisted that I wanted them to be safe. She left early in December 1963, arriving in Britain shortly before Christmas. Our friend Wolfie Kodesh was there and David leapt into his arms, so at least there was one person he knew in London. Unfortunately we were so closely guarded I could not escape. Bram and others felt it would be a great political victory if we could escape amidst such heavy security and if anyone among us could it would be me. Bram also knew that there was a mass of evidence against me and the death penalty was a real possibility for me.

The prosecution had a very strong case against us: masses of documents and many witnesses. Jimmy Kantor, the brother-in-law and law partner of Harold Wolpe, was acquitted before the defence case began because there was no case against him. We all felt that he was charged so that the prosecutor could take revenge for Harold’s involvement in our activities. Jimmy’s legal practice was ruined and he went into exile with his family. He died a relatively young of a massive heart attack in 1975. Our lawyers also called for Rusty’s Bernstein’s acquittal for lack of evidence. The judge however said he had a case to answer. The great day came: the opening of the defence case. Our defence began with Nelson Mandela’s famous Speech from the Dock. He needed to present our political case without the interruptions of questions by the lawyers. Even though he had been the star witness in the Treason Trial we decided he should not be subjected to intolerable cross-examination, such as whom he had met and what discussions he had had when he left the country without a passport in 1962.

In the shadow of the gallows, Nelson Mandela’s speech was a masterpiece of legal defence and immensely courageous political statement. We had all seen the speech and commented on it - and the lawyers had analysed it from their point of view. Yet it remained Nelson’s speech, written in his large round-hand manuscript. When he came to the final paragraph - where he said he hoped to live to see a South Africa free of racism, where people could live together in harmony, but if needs be he was prepared to die for this ideal - he spoke in the same tense but measured style of his four-hour-long presentation. His words were a clear challenge to the judge and apartheid South Africa, to hang him if they dared to. At that moment I realised he was also challenging them to hang all of us. I could feel only pride at sharing this wonderful moment. Being on trial for your life is not something you choose. You do not go to prison. You get taken! But what a moment in my life that was. I can truly say that we have looked death in face and come through the experience as better, stronger people.

After Mandela, for a very long four days in the witness box, Walter Sisulu, quietly, by force of personality, dominated the proceedings He set out to explain why we had taken up arms to commit acts of sabotage but had not yet taken a decision to embark on full-scale guerrilla warfare. He withstood fierce cross-examination by the prosecutor Yutar, who seemed to think that he knew more about politics than the Secretary General of the African National Congress. Walter was calm and masterly, absolutely overshadowing the pettiness of the prosecutor’s ill-informed political questions and arguments. These were based on the typical white South African’s belief that they held the key to civilisation and thus had the right to treat all black people as silly children who did not know what was good for them. Only once did Walter lose his cool. Yutar had presented some spurious argument to say that life for black South Africans was not so bad after all. Walter flashed back: “I wish you could live for just one day as we are forced to do and you would not make such a remark.”

Govan, Rusty and Ahmed Kathrada all gave evidence of why they had been involved. Kathy was notably humorous. Asked if he knew anybody with the initial K, clearly a reference to himself in one of the documents being used in evidence, he replied Kruschev, the Soviet leader. This led to a time-wasting but enjoyable exchange between prosecutor and accused. All three of my comrades gave remarkable public lessons in political commitment and rational analysis as the basis for the policies of the Congress Alliance and the South African Communist Party. The prosecutor Yutar opened the way for all of this by the nature of his cross-examination. We had decided that though we were giving evidence, we would not under cross-examination by the prosecutor betray the names of comrades whose liberty would be put at risk. That meant we were not prepared to comply with our oath or affirmation that one would “tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth”. The judge told Rusty that he had to answer questions put to him. He declined. The judge said he could imprison him for eight days at a time until he did answer. Then added, “but that would not change your mind, would it?” The trial went forward.

Ray Mhlaba did not fare well in the witness box. He had been in the People’s Republic of China for military training and the police and prosecutor were aware of this fact. He had had a large cyst removed from his forehead while he was away. He would not admit where he had been because that would perhaps give the judge an excuse to say we were ready to implement our armed uprising. He became flustered and the prosecutor, knowing that Raymond was not present when certain events took place insisted that he was present. In democratic court procedure the prosecution is required to make known facts that are to the advantage of the accused. In fact Raymond was not guilty of many of the things he was charged with because he had been away.

I too gave evidence because I wanted to explain why I had been prepared to give up all the privileges of white racist society to help bring about a just society in which we would one day live in harmony. Our judge from time to time showed that he too was imbued with the typical racist attitude of what he believed was his self-evident right. The lawyers were worried that I might antagonise the judge who indicated that he thought of me as the Smart Aleck who stirred up “poor but happy blacks” to become “cheeky” revolutionaries as racists liked to say about the oppressed. The lawyers were worried that he might be pushed to hang me because the whites would like that and black people would not be as upset as they would be if my black comrades were hanged. I knew this was a real possibility, but it was not always uppermost in my mind. What was important was that white and black South Africans should see that there are people of all races who believe in equality. I was quite respectful of the judge but called him “Sir” rather than “My Lord” and on coming into the witness box would nod and greet him with a cheerful “Good morning” to which he felt compelled to reply equally politely.

There was also a legal reason for giving evidence. George Bizos had found a precedent in a judgment involving Nazi supporters during World War II who had investigated the possibility of an uprising against the pro-Allied government in South Africa. Preparation was not an offence or not a serious offence, unless a decision had been taken to go ahead with an armed uprising. My task, I said in evidence, was to investigate as an engineer the possibilities of producing our own weapons “if they should be needed”. A decision to go ahead would be influenced by whether we could produce the arms we needed. Therefore my activity was merely that of a technical adviser to responsible political leaders who needed facts on which to base their decisions. That was my role and I did not feel it necessary to inform the court that our Logistics Committee of our High Command had decided that, even if Operation Mayibuye was not adopted, weapons would be required for ongoing sabotage and we would make them. I also did not feel it necessary to inform the court that I was a member of the MK Western Cape Regional Command. Nor did I feel it necessary to admit that the camp at Mamre in December 1962 was indeed the first MK training camp inside South Africa. They inferred the nature of the camp but I would not concede the point. They could not prove these things and I did not think the judge needed me to confirm their inferences. My conscience has troubled me ever since. But only a little.

For some reason Dr Yutar left my cross-examination to his assistant, thus depriving me of the opportunity to confront the petty little tyrant whom the security police had said was “one of my people” who was going to hang me. How such little ambitious people sell themselves to satisfy their ambitions and become the willing servants of tyranny. I ran into trouble right at the end of the cross-examination when I was asked if I had bought the new place at Travallyn for the ANC or for MK. I had to say it was bought for MK though it would have been easy to say it was for the ANC - and if I were believed it would let me off one of the hooks, that of buying a headquarters for MK but “merely” for the ANC. However, a major issue in the trial was whether we could convince the judge that, though some leaders of the ANC and the SACP were members of the MK High Command, each was a separate organisation with overlapping membership but separate functions. This was important so that every member of the ANC or SACP was not automatically, in terms of the law, a member of MK, and the other way round. Indeed this division of functions and membership was true because most of us believed that military action is too important to leave to military people alone. Political considerations must determine the strategy and tactics, especially of a war for political liberation. This issue affected me because I had been the person who had bought the new place. It fitted exactly the type of place described in a document about setting up the weapons manufacturing facility for MK, disguised as a poultry farm. The document was found among our papers at Travallyn.

I did not feel it was necessary to tell the court that I had typewritten the document and there was too little handwriting on it for the experts to identify it as mine. In the face of that document I could not say that the place had been bought for the ANC underground headquarters because that would have tied the ANC into being MK. Of course, the little opening that George Bizos had found for me closed with the clang of steel doors. However, one is merely a part of a much bigger whole and preserving our movement was more important than trying to save myself. I felt pleased with my performance for having been able to say why I had been prepared to risk everything in the cause of justice in our country and not succumb to personal self-interest at the expense of our liberation movement.

Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni each read a statement from the dock rather than go into the witness box. Neither had been at Liliesleaf and they had operated at the level of the Johannesburg Regional Command rather than the High Command. Their statements were dignified and passionate explanations of why, as patriotic South Africans, they felt they had no choice but to take part in the armed struggle, after years of peacefully knocking on the door of apartheid South Africa to be allowed in to share equal rights for all. There was often time for individual conversations during consultations. Nelson one day took me aside and, with his finger wagging for emphasis, said without preamble that when we taught Marxist theory to our people we must relate it to the lives of South Africans. He went on to say that speaking of social development in Europe from barbarism through slavery and feudalism to merchant and industrial capitalism had no meaning for our people. We had somehow to relate the theory to fairly egalitarian tribal life, to the pressures of colonial conquest and the leap into industrial capitalism in a very short time. What had taken 600 years in Britain, for example, took about 100 years in South Africa. The truth of his observations was self-evident but why, I asked him, was he telling me? He shrugged without giving a real answer, merely saying that he wanted me to know his thoughts on the matter. I believe he thought he was going to be hanged and I might not be and he wanted me to carry his message forward. Nelson has always denied being a member of the Communist Party but from the notes he made and that were presented in the trial he certainly had studied Marxist theory very thoroughly indeed. During his address to the court he said that there were many attractive aspects to the theory but he implied that as a leader of a national liberation struggle he needed to transcend any one political ideology to build the greatest possible unity.

During another consultation towards the end of the trial, Ray Mhlaba spoke to me separately. He said: “Comrade, we have decided after discussions” – I was kept in a separate part of the prison because apartheid racism applied there too – “that if there are death sentences, we should not appeal.” I asked: “Why not?” And he said: “Because we want to get out of the way. We must let them hang us. Our people will be so angry they will rise up and sweep away the apartheid system.” I responded: “That’s a very interesting theory, but I believe that governments do not hang political leaders until they’ve got things under solid control. And then they will deal with one and then another and so on and they will be really on the alert to keep control. It’s not going to be as easy as you think. And more than that, it has taken 30 years to make you the leader you are and I don’t think we should throw you or the others away. We must use every means to keep you alive. We’re going to need you.” He thanked me for the compliment.

Two weeks before his death in 2006 we were still joking about that conversation. He said, “Well, you see, comrade, we didn’t need to make the choice, did we?” Bram Fischer said he would insist on appeals if there were death sentences, the reason being that the hysteria in South Africa would die down after a while. Among the media, representing the views of the whites, there was pressure for us to be hanged. Nonetheless, Bram argued, there would be time to organise increased international pressure on the apartheid regime. So, even if we lost the appeal and were executed, the end of the system would be hastened. The day before sentence was to be passed the judge had found most of us guilty on all four charges against us. Ahmed Kathrada, on the evidence presented, should have been acquitted but was found guilty on one charge only. Had he been acquitted he would have been tried on other charges to which the evidence and his own explanations had exposed him. Rusty was acquitted and I have no doubt that his insistence on seeking bail, as though he were really innocent, helped him, though it was the prosecutor’s failures that really let Rusty off the hook. Yutar had become so engrossed in his political confrontation with Rusty that he forgot to put fundamental issues of fact to Rusty. Rusty’s declaration that he had not done the things alleged in the indictment had therefore to stand.

On 12 June 1964, the day of sentence, the judge read a very short statement saying that he was not imposing the maximum sentence (death) which would be appropriate in a case that was tantamount to high treason, but as we were charged under the Sabotage Act the sentence was life imprisonment on each of the charges on which we were found guilty. As he spoke the faces of my comrades lit up in the most wonderful smiles of relief and joy and we laughed out loud. I was overjoyed to live even though it would be life behind bars for a very long time. I was only 31 years old and I did not believe that my life was over.

I suspect that we were fortunate in having the prosecutor we did have. Dr Yutar’s personal animosity and his false assumption of moral and intellectual superiority led him into political arguments with some of my comrades in the witness box while neglecting the legal basis of the case against us. Yutar was really out to hang us by political argument in the court of public opinion and he neglected to provide a thorough basis of legal presentation and argument. He charged us under the Sabotage Act because it gave the prosecution an enormous advantage: it alone in South African law overturned the principle that an accused was innocent until proven guilty. This sabotage legislation provided that, if the prosecution could show that there was a case to answer, the accused had to prove their innocence. That is very difficult to do, even when you are completely innocent.

Yutar the prosecutor, in painting us as desperate people who were mere terrorists, plus his antics and craving for dramatic headlines, was probably counter-productive for the state. True, throughout the trial, the mainstream newspapers were extremely hostile to us, but their reports and their frightening headlines may have done them more harm than good. While whites would have been shocked into baying for our blood when they read that I, for example, was to make 210 000 hand-grenades and 48 000 landmines; black South Africans would have rejoiced at the plans we were developing. The mainstream pro-apartheid media did our propaganda for us. At the same time, Laurence Gandar, editor of the Rand Daily Mail, ensured that what we were saying was prominently carried by his paper on a daily basis. In a series of front-page editorial pieces Gandar asked what was wrong with white South Africans who had instituted and supported policies that turned patriotic, well-educated and serious responsible people like Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela and Chief Luthuli, among many others, into determined freedom fighters. On the basis of his analysis Gandar felt that white South Africans had to recognise that enforcing apartheid laws made the security of whites more problematic rather than making them safer. They needed, he said, to open up society to ensure that black people could lead decent lives so that whites could live in peace without any sense of fear. Gandar did not accept that armed struggle was legitimate, but he was opposed to the style of prosecution that Dr Yutar resorted to: i.e. seeking to humiliate the accused and wanting to belittle us with his arrogant white-superiority attitudes.

Gandar’s coverage was a remarkable show of editorial independence in the face of white hysteria. His paper was owned by the giant Anglo-American Corporation whose founders said they were liberal in their politics but through their business activities gave their full support to the apartheid state. For his continued opposition, which led to the falling circulation of his paper and therefore falling advertising revenues, Gandar was fired. Profits triumphed over integrity. Before we were taken back to the prison, our lawyers said they had permission to see us the next day to discuss the question of an appeal to a higher court against the convictions and sentences imposed. There was a long delay while the police made sure that they had everything under control and then we were finally taken back to prison. As we made our way out of the court the massive crowd of our supporters sang our anthem, Nkosi Sikelela iAfrika, and shouted that we would not serve our sentences. A convoy of trucks and cars loaded with police surrounded our truck and a squad of motorcycle cops led the way with sirens screaming.

At the prison we were again separated and I was taken off to the white section of the prison. Colonel Aucamp, the head of the Prison Security Division, seemed quite pleased at the outcome of the case though when I remarked that he seemed as pleased as a cat that had licked the cream, he responded quite bitterly that we should have been sentenced to death. He proclaimed that though we had life sentences we would never leave prison on our own two feet. “You will be carried out feet-first in your coffins.” I am happy to confirm that he was wrong. From the time we were arrested at Liliesleaf, the whole process took 11 months: three months of 90-day detention, then eight months of trial. We were arrested on 11 July 1963 and sentenced on 12 June 1964.

In my cell I smoked a last few cigarettes, feeling quite calm as I waited to be processed as a convicted prisoner. Prison clothes were issued to me and all my private clothes and possessions, letters, photographs of my family and books were taken away. In no time at all I met up with Jock, Ben and Jack who were to be my companions as fellow political prisoners for many years. The lawyers, who had said they would see us, were not allowed to visit and I heard later that my comrades had all been flown to Robben Island during the night. I was the only Rivonia trialist left in Pretoria.

The day after we were sentenced my Mum and Dad came to visit me. They had been separated and divorced for years but they were together to see me because the number of visits was strictly controlled and at first we were allowed only one visit each six months. Dad, who had worked so hard so that I, his younger son, could have a university education, said he was pleased with me for not flinching in the face of the injustices they had both taught me to understand and to oppose. My Mum, who had not allowed herself to show any weakness in public, rather tearfully said that her life was fulfilled through me. She would shortly leave for Britain to join my wife Esmé and our children. Dad would stay and be my visitor. So ended my first half-hour visit.

After some days Major Gericke, the Commanding Officer, told me with what seemed to me to be deeply felt emotion that Mollie Fischer, Bram’s wife, had died in a motor accident. He gave me permission to write a short note of condolence to Bram. The letter was not sent. Bram must have been devastated by her death. They were such a close couple who seemed inseparable in their marriage and in their political commitment. Bram and Joel came together to see me some weeks later to talk about an appeal against the sentences imposed on all of us. They said: “We have been to the Island. Your comrades feel there is no point in appealing the sentences.

We think there is a risk that the Appeal Court might either increase the sentence or simply remark that, while they were not imposing the death sentence, all of you were fortunate not to have been sentenced to death. That would be an invitation to judges in future trials to impose death sentences. The criterion is “does the sentence cause a sense of shock?” We knew that most whites would have preferred death sentences and many would have been disappointed that we had been sentenced to life imprisonment. Judges are not immune to the feelings and sentiments of the society of which they are a part. I said to Bram: “The judge by sentencing us all to life imprisonment made no distinction between degrees of guilt of each of us.” Bram responded that what the judge had done was to say that the minimum sentence he felt he could impose was life and that there was nothing heavier than that, other than death sentences. I would not go against the wishes of my comrades and really felt that we were lucky to have escaped with our lives. During the trial our lawyers were worried that the prejudices of the prosecutor and the judge might lead the judge to sentence me to death for being the one on hand whom he could sentence to death for stirring up my black comrades. I knew it was, in fact, the other way round: I was there to serve a cause led by such great people.

During the short consultation Bram did not mention Mollie, nor did Joel. Bram was thinner and extremely pale. When I expressed my sorrow at her passing and my sympathy for him, Bram simply looked down, became even paler and did not answer. I was able to reach through the bars of the grill separating us and squeeze his hand. He allowed no more emotional contact than that, screwing up his eyes to stop tears from falling. I did not see Bram again until 1966, after he’d been sentenced to life imprisonment and we ended up as prisoners alongside each other.

Our Rivonia lawyers each in their own way continued with their fight against apartheid and some play significant roles in democratic South Africa. Arthur Chaskalson continued to use the courts to defend democratic principles. He played a leading role in establishing the Legal Resources Centre and became the first President of the new Constitutional Court and then Chief Justice. George Bizos became a leading civil rights lawyer and is chairperson of the governing body of the Legal Resources Centre in Johannesburg. Joel Joffe, shortly after the end of our trial, was forced to leave South Africa by the harassment of the security police who frequently raided his office, seizing confidential documents and statements of those he was defending. He became a successful business man in Britain and later President of Oxfam. For the latter he was made a life peer, a British Lord. He actively supported the liberal press in South Africa in opposition to apartheid. He has always been a kind friend to me. Vernon returned to retirement and passed away some years later.

Burned out, alone …

Burned out Alone I lie Eat sleep Body meets calls All All within four walls. Months, years Pass slowly When days seem long Always the same – Nothing done Nothing achieved Thoughts focused only on oneself Behind the walls. Far off Carried softly on the night wind A clock strikes the hour In the morning The town rumbles There Outside the walls People live their lives Factory sirens call their workers Diesel locomotives shunt And couplings clatter Cars hoot and machines drone Their beat Even muffled by the walls Saves me from doubt But it isn’t easy for thoughts to fly When body and mind are in a stall But on the rising wind My thoughts become sharp and focused take wing take the right attitude Fly Clear Over the walls Meet with life Striving Joining in The contradictions Of life out there to build anew and turn my defeat into victory