Related Collections from the Archive

With the rise of apartheid in 1948, millions of Africans were left to suffer in South Africa. Many groups rallied against the Afrikaner government through political activism to change the future for the African people and free them from the white regime. Men such as Nelson

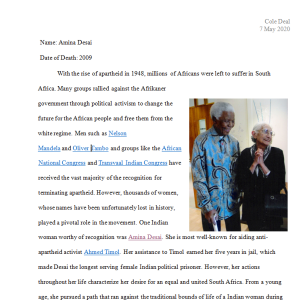

Mandela and Oliver Tambo and groups like the African National Congress and Transvaal Indian Congress have received the vast majority of the recognition for terminating apartheid. However, thousands of women, whose names have been unfortunately lost in history, played a pivotal role in the movement. One Indian woman worthy of recognition was Amina Desai. She is most well-known for aiding anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol. Her assistance to Timol earned her five years in jail, which made Desai the longest serving female Indian political prisoner. However, her actions throughout her life characterize her desire for an equal and united South Africa. From a young age, she pursued a path that ran against the traditional bounds of life of a Indian woman during the 1900s. Amina Desai served her country not as a prominent vocal activist, but devoted her life to influence others in small roles that would make the world a better place by example, with the lives of her children driving her the entire way.

Daughter to an Indian father and Malay mother, Desai was born in South Africa in 1919.

She did not have an aggressive interest in politics, but simply sought to earn an education from

an early age.[1] Her father pulled her from school when she was ten to take care of her younger siblings. Still committed, at home, she enrolled in a school for midwifery in hope of becoming a nurse before her father again forced her to stay home. Desai eventually persuaded her father to allow her to attend Harvard College. At the time, Harvard College was an all-white school located in Johannesburg. She earned qualifications in commerce, shorthand, and typing.[2] The resilience that Desai displayed as a young girl to earn a formal education stayed with her throughout her life.

Amina Desai began her professional career writing with her sister for the Indian Views? magazine. Under pseudonyms, they wrote about feminism and the role of women in society. In May 1943, Amina became Mrs. Desai when she married Suleiman Desai.[3] This is where her political battle towards South African freedom began. Together, Amina and Suleiman had four children together.[4] By the 1970s, all of their children had escaped apartheid and fled overseas to Europe. Suleiman, a founding member and secretary of the Transvaal Indian Congress, would engage in passive resistance campaigns during the anti-apartheid era. Here, Amina became acquainted with many of the Transvaal Indian Congress members such as Yusuf Dadoo and Ismail Cachalia. Sulieman owned a shoe store under Watson’s shoes, a popular local brand. Unfortunately, Suleiman passed away in 1969 after a heart-attack. Business owners were primarily males during this time in South Africa, yet Amina continued to run the business at will, an incredible feat for a woman during this era as she was one against many. Desai successfully ran the shoe store for the next 35 years until she will be forced to leave South Africa because of her health.

Desai agreed with her husband’s views. But, she did not have a strong desire to speak out against apartheid. Desai stated, “I was, have been a pacifist all my life. I have also of course been very - in the old days we used to call it feminism. I believed in that, absolutely.”[5] Although she was never a formal member of a congress or any formal anti-apartheid group, she continued to support the movement and had strong opinions towards those who enforced it after the apartheid era. She believed that there were others who were more competent that were able to get her views across to the public. Desai carried a subtle, behind the scenes approach, for most of her career.

Instead of being a vocal leader, she supported the movement through small actions. For over fifty years, she lived in Roodepoort, a suburb of Johannesburg.[6] Desai’s proximity to Johannesburg enabled her to support local activists in the area. After 1960, many of the well-known leaders of the ANC and TIC were forced to live ‘underground’ to escape imprisonment. Thus, anti-apartheid supporters, like Mrs. Desai, opened their homes to these groups to offer a safe home from the city’s police force. Nelson Mandela relied on similar safe homes for years before his imprisonment.[7] Desai provided a safe shelter for Ahmed Timol, a young supporter of the ANC and SACP.[8] Timol, born in 1943, was the son to Indian immigrants. He spent most of his childhood in Roodepoort where he became close with the Desais. In exchange for running errands for her, for she did not have a license, Mrs. Desai allowed Timol to stay at her house and use her car on occasion. Timol and the Desai’s son, Hilmi, worked closely together printing anti-apartheid pamphlets.[9] While in her home, Mrs. Desai and Timol often discussed politics. The telephone technicians visited the Desai home often, which made Mrs. Desai believe that her telephone was tapped.[10] However, she did not keep constant taps in Timol’s plans and actions.

On October 22, 1971, Desai fell victim to the apartheid government with hundreds of other activists when the police swept the nation in the night. ? Timol and his friend Salim Essop? were stopped by the police at a roadblock. They were arrested in Coronationville after the police found “communist literature” that had detailed plans of the South African National Party. Timol was driving Mrs. Desai’s car when he was arrested. As a result, at 3 am that same night, the police raided the Desai home just as Mrs. Desai was attempting to destroy Timol’s journal.[11] After they searched her home for five hours, the police arrested Mrs. Desai. The police took her, along with Timol and Essop, to John Vorster Square, a nortious police station during the apartheid era. That night, the police arrested over a hundred people as political prisoners, among which included Amina Desai and Ahmed Timol.

At John Vorster Square, the police interrogated all political prisoners through cruel methods, with the intent of breaking their spirit. Desai was interrogated for four days straight as she explained, “They had teams of interrogators. Of course there (is) no rest in-between.”[12] The state used this as a tactic to break prisoners so that they could get information. The investigators threatened and beat those, like Desai, which led to many prisoners’ death. While the interrogators were investigating Mrs. Desai a few days after the arrest, they heard a large commotion on a floor above where she was being held. People were shouting and furniture was being thrown around the room when Ahmed Timol ‘fell’ to his death from the 10th floor of the building. The police claimed Timol jumped to his death. However, later, Gordon Winter, an undercover agent for South African Intelligence, wrote that Timol had been held by his feet from the window during an interrogation when one of the officers lost their grip.[13] Mrs. Desai would not learn of Timol’s death until her trial in court. When she was being questioned about the papers in her home and car, Mrs. Desai stated that Timol could explain. Only then did her lawyer inform her of Timol’s death.[14]

Under the Section Six of the Apartheid Legislature, Desai was held in John Vorster Square in solitary confinement for four months, until her trial in March, 1972. Desai, rightly so, believed that she had not committed any crimes. She had not formally committed to any anti-apartheid congress or believed in any communist government formations. In her recollection with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Desai explained, “I felt my conscience was clear. I hadn’t done anything wrong.”[15] The trial took place in the Old Synagogue in Pretoria, the same place as the Treason Trial and many other political court cases during apartheid. The court questioned her for the many books she had in her home. Throughout her life, Desai prided herself on her education and her children’s education. Desai recalled in questioning in court, “He (Timol) used to sit and study in my house. He had some books there, but of course he used to leave his briefcase there and his books there and I never bothered to go through his cases and his books.”[16] Desai never wavered in her claim to be innocent. The court sentenced her to five years in prison under the Terrorism Act, which would be followed by five years of house arrest. Salim Essop, the young man who had ridden in the car with Timol, was charged under the same crime as Desai and sentenced to Robben Island until his release in 1977.[17]

For the next five years, Desai served time in Barberton and Kroonstad Prisons, respectively. Some people portrayed a different image of Desai than the one we see today during her early years in prison with regards to her attitudes towards others. Dorothy Nyembe was an African female political prisoner who served in Barberton with Mrs. Desai. A human rights monitor described Mrs. Desai to be “rather racist… complaining of having to share meals with a black woman (Dorothy Nyembe).”17 On top of being characterized as racist, she was seen as

“non-political.” Her lack of interest in politics led some to question whether she had even been guilty of treason in the first place. Based on Desai’s earlier statements prior to the trial, she questioned the same thing as well. These accounts have only been confirmed by the social worker. Many in the Indian community are hurt by this characterization. With little known about the language barrier or the circumstances in the interview between the human rights worker and Desai, this is all we have to go by on this account.[18] After spending time with Nyembe, Desai became more and more passionate about politics. By the end of her term, she was characterized as being “more fiery against apartheid than Dorothy!”[19] Amina Desai went into prison with limited direct interests in politics and became just as passionate as the anti-apartheid lead activists.

Along with Nyembe, Desai served with Winne Mandela at Kroonstad Prison. Together, the political prisoners were kept in their own sealed portion of the prison. Anima became a part of Winnie’s close circle in prison. At Kroonstad, the women in this section each had their own cell with a bathroom and a courtyard to share, a luxury during this period.[20] The impression that

Desai made on Winnie in prison would last the rest of their lives. Only a few days out of prison, Winnie wrote to Amina’s daughter overseas. In the letter, Winnie wrote, “Dear Adela, On behalf? of your mother whom I served 6 months with, accept this little card. I wish you the best of everything. She sends you her fondest regards. She thinks of each one of you daily.”[21] Throughout her time in prison, Anima’s children remained at the front of her mind. The impression Desai left on Winnie gives great insight to the character she displayed in her later years in prison contrary to the human rights worker’s initial description. Desai continued her relationship with the Mandelas after prison. Because of her banning orders, Winnie was not allowed to hold a job once she was released from prison. After Desai was released in 1978, Anima sent Winnie shoes and clothing from her store for support.[22] After her release, Desai continued to run her late-husband’s store. This would continue on for the next fifteen years.[23]

In 1996, she testified for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission regarding her life and the events that transpired before and after the time of her arrest. Desai maintained her own? opinion on what one’s main impact should be through their life and through the anti-apartheid movement. In her interview with the TRC, she stated,

“who (I) felt that they (parents in society) really could not contribute excepting in their own small way, perhaps with their own children. That was the contribution you make to society. You try and foster in your children a care for humanity. That is all that you can do as a human being, that you should care about what happens to people.”[24]

Throughout her life, Desai attempted to stay out of the spotlight, which explains her reluctance to commit to an anti-apartheid congress. There is little information about her outside of what can be gathered from her kin or government documents.

In 2004, due to old age and diminishing health, Desai retired to join her family in the UK and Ireland, where three of her children had settled after they fled South Africa.[25] She would later attend the Freedom Day celebrations in Ireland, which were hosted by the South African Ambassador, Priscilla Jana, a member of Desai’s legal defense team.[26] She passed away on June 10, 2009. She was 89 years old.

Amina Desai was committed to leaving a legacy that was bigger than herself. She wanted to have an impact on the world that would not better her own life, but her children’s lives and the one’s they affected. She stated in 1996, “We should really live as simple a type of life and try and - the important thing is really to educate our children. The most important thing here, I think is to teach people, to make people aware of humanity as such and that we are here, not merely for ourselves, but to try and make the world a better place.”[27] Even during her time in prison, Mrs. Desai’s largest fear was that her children would risk their freedom and return to South Africa to help her. With her children’s escape from South Africa, they continued their mother’s legacy. Mrs. Desai’s grandson, Adam Bainbridge, is a Grammy award winning music producer.[28] Amina Desai enabled her children to carry on their lives and spread her values of education and good nature throughout the world.

To cap off a life filled with heroic achievements, but also so many untold mysteries along the way, Desai received the Order of Luthuli posthumously in 2013. This National Order of South Africa is awarded to those “who have contributed to the struggle for democracy, nation? building, building democracy and human rights, justice and peace, as well as for the resolution of conflict.”[29] This honor deservingly recognizes Desai for her actions during the apartheid era.

Amina Desai will be remembered for her persistence to enrich her life and her family’s life in order to leave the world more full of thought and care than when she arrived.

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project

[1] “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa.? Accessed April 4, 2020. http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/national-orders/recipient/amina-desai-posthumou?s.?

[2] Leila Blacking and Adam Bainbridge. “Obituary: Amina Desai.” The Guardian??. Guardian News and Media, June 21, 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2009/jun/22/obituary-amina-desai-south-africa.?

[3] “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa.?

[4] United Nations: Unit on Apartheid, (1975). ‘Women Against Apartheid in South Africa’ Department of Political and Security Council Affairs?. Available at https://disa.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/pdf_files/rep19751100.037.051.001.pdf

[5] Mrs. Amina Desai (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation?Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?. Available at https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/hrvtrans/krugers/desai.htm

[6] “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa.?

[7] Nelson Mandela, ?Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela? (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1994), 241.

[8] “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa.?

[9] “Ahmed Timol.” South African History Online. Accessed April 20, 2020.

[10] Mrs. Amina Desai (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation? Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[11] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions?

[12] Mrs. Amina Desai (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[13] Fran Lisa Buntman (2003). ?Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance Apartheid?, Cambridge University Press.?? Pg. 2.

[14] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions? and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[15] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions.

[16] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions?.

[17] Martin Coldrick. “Nelson Mandela: A Fellow Robben Island Prisoner's Memories.” BBC News. BBC,

December 5, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-leeds-2305375?7.?

17 Fran Lisa Buntman (2003). Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance Apartheid?, Cambridge University Press. Pg. 2.

[18] Raymond Suttner (2004). “Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid? Review.” H-Net? Reviews in Humanities and Social Sciences. ?Available at https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=9977

[19] Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance Apartheid,? Cambridge University Press. Pg. 2.

[20] Anné Mariè Du Preez Bezdrob. Winnie Mandela: A Life?. Cape Town, South Africa: Penguin Random House South Africa, 2011.

[21] Winnie Mandela (1975). ‘Season 1, Vol. 1 Episode 1: Kindness - “Aunties Aren’t Stupid” Bad Brown?Aunties?. Available at https://www.badbrownaunties.com/blog/2019/6/4/season-1-volume-1-episode-1-kindness-aunties-arent-st upid-e6jbe

[22] Season 1, Vol. 1 Episode 1: Kindness - “Aunties Aren’t Stupid” Bad Brown Aunties??.

[23] “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa.

[24] Mrs. Amina Desai (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation? Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[25] Mrs. Amina Desai (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[26] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions? and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[27] South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions? and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp?.

[28] Winnie Mandela (1975). ‘Season 1, Vol. 1 Episode 1: Kindness - “Aunties Aren’t Stupid” Bad Brown? Aunties?.

[29] “National Orders to Be Bestowed on Deserving Recipients.” SAnews, April 22, 2013.

https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/national-orders-be-bestowed-deserving-recipients.?

Primary

- Barberton Museum. (Picture of Amina Desai). Available at https://www.umjindi.co.za/menu/history/museum/exhibits/female-activists-prisoners/amina-desa i.html [Accessed 5 April 2020].

- Desai, Mrs. Amina, (1996). South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Human Rights Violation Submissions - Questions and Answers, Mrs. A Desai, Krugersdorp. Available at https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/hrvtrans/krugers/desai.htm

- Mandela, Winnie (1975). ‘Season 1, Vol. 1 Episode 1: Kindness - “Aunties Aren’t Stupid” Bad Brown Aunties. Available at https://www.badbrownaunties.com/blog/2019/6/4/season-1-volume-1-episode-1-kindness-auntie s-arent-stupid-e6jbe

- South African Press Association, (1996). ‘Woman Tells TRC She Was Jailed for Lending a Car to a Friend’ Kasigo November 13 1996 - Sapa. Available at https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1996/9611/s961113a.htm

- United Nations: Unit on Apartheid, (1975). ‘Women Against Apartheid in South Africa’ Department of Political and Security Council Affairs. Available at https://disa.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/pdf_files/rep19751100.037.051.001.pdf

Secondary

- “Ahmed Timol.” South African History Online. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol.

- “Amina Desai (Posthumous): The Presidency.” The Presidency. Republic of South Africa. Accessed April 4, 2020. http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/national-orders/recipient/amina-desai-posthumous.

- “Amina Desai.” South African History Online. Accessed April 01, 2020. https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/amina-desai.

- Blacking, Leila, and Adam Bainbridge. “Obituary: Amina Desai.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, June 21, 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2009/jun/22/obituary-amina-desai-south-africa.

- Buntman, Fran Lisa (2003). Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance Apartheid Cambridge University Press. Pg. 2. Available at https://books.google.com/books?id=dQbCzR0AHtkC&pg=PA2&dq=Amina+Desai&hl=en&new bks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjKqf_8qJjoAhWula0KHfbHC0UQ6AEwAHoE CAMQAg#v=onepage&q=Amina%20Desai&f=false

- Coldrick, Martin. “Nelson Mandela: A Fellow Robben Island Prisoner's Memories.” BBC News. BBC, December 5, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-leeds-23053757

- Mariè Du Preez Bezdrob, Anné. Winnie Mandela: A Life. Cape Town, South Africa: Penguin Random House South Africa, 2011. Available at https://books.google.com/books?id=awtbDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT255&lpg=PT255&dq=amina+des ai+kroonstad&source=bl&ots=u4PRglhXuw&sig=ACfU3U1_DEq-Uhxt2NxmpfIfWSbO7J0PIw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwihoL-VgvvoAhUBUKwKHUQMC3IQ6AEwBnoECA0QAQ#v=onepage&q=amina%20desai%20kroonstad&f=false

- Mbatha, NPZ (2018). Narratives of Women Detained in the Kroonstad Prison During theApartheid Era: A Socio-Political Exploration, 1960-1990 Women’s State in Prison. Pg. 105.

- “National Orders to Be Bestowed on Deserving Recipients.” SAnews, April 22, 2013. https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/national-orders-be-bestowed-deserving-recipients.

- Suttner, Raymond (2004). “Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid Review.” H-Net Reviews in Humanities and Social Sciences. Available at https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=9977